Few romances are as cursed and enduring as the tragic love story of man and the ocean. Humans have been venturing out onto the water since the earliest days of our social life: depictions of boats are featured in ancient cave art, and the use of waterways and seas as systemic transportation arteries is among humanity’s oldest technologies. People love the sea for its beauty, its bounty of delicious assorted fish, and its place as the interstitial connecter of the world. And yet, the ocean is trying to kill us. It slices ships apart with icebergs, it rams them under with enormous waves, it spins up colossal hurricanes, and heaves tidal waves and tsunamis into our cities. It killed the Crocodile Hunter.

Navigating the ocean safely is no easy task. Today it is far safer than it has ever been, but even with modern shipbuilding, communications, weather forecasting, and rescue infrastructure, the ocean is still more than capable of claiming fresh victims.

Humanity, of course, had to complicate matters by bringing political life out onto the water. The ocean is trying to kill us, but it was not long after the first navigators set out onto the water that humans also began trying to kill each other on the ocean. Naval warfare - the organized armed struggle of men (who are, after all, terrestrial creatures) on the waterways and seas of the world - is very old indeed, and forms an integral component of some of the first recorded wars in human history.

In this essay series, we will consider man’s history of maritime violence and his warring on the seas. Man wants to become master of the sea, and while this necessarily implies the mastery of navigation, it also requires mastering the other men that one finds out there on the waters. For all its formidable powers of destruction, the sea could not keep men out, and once man was on the water he made it another arena of his foundational political act, and made war. And so it has been, and so it will be, until the sea gives up her dead.

Naval Operations: A Conceptual Sketch

The motivating animus of naval warfare is not as readily apparent as that of conventional land operations. The idea of fighting overland campaigns is fairly easy to grasp. One seeks to neutralize the enemy’s capacity to fight (and thus impose your will upon him) by degrading or controlling his base of material power: occupying his capitol city, severing his control over his population, destroying or capturing his economic base, etc.

The plain point, however, is that none of these things are conventionally found out on the open water. The foundation of the sea’s strategic import, therefore, lies in its role as a transportation medium. This has been true for quite literally all of human history. Archaic man found that it was far more efficient to float materials on barges than it was to haul them with pack animals. In the early modern era, it was ironically far easier to economically link far flung maritime colonies than colossal land masses (unless there were robust river linkeages), and it was only after the invention of the railroad that continental interiors became competitive. Perhaps the most famous example of this is the Crimean War - in the 1850’s, seaborne supply and communication were far faster and more efficient for the invading French and British armies than for the defending Russians, despite the war being fought within Russian borders. Famously, British reinforcements and supplies took a mere three weeks to reach Crimea via the sea, while Russian material took three months to slog to the battlefield on foot.

Because the sea fundamentally acts as a medium of transportation, naval operations therefore take on a surprising simplicity. Virtually all naval combat in history can be categorized in two general groups, these being amphibious power projection and interdiction.

Amphibious power projection is fairly easy to understand, and it means simply the use of naval assets to bring armed force to bear against targets on land. The form can vary wildly, of course - ranging from Viking longships disgorging a small army of raiders, to British sailing ships bombarding enemy fortresses, to modern amphibious landings such as the 1944 assault on Normandy, all the way to the contemporary American navy operating sorties from colossal nuclear powered aircraft carriers. In truth, there is not much of a conceptual difference between any of these things - the mobility and carrying capacity of the sea in all cases allows fighting power to be rapidly shuttled to decisive points.

Interdiction is the other form of the naval operation, and it means simply area denial - hindering or preventing the enemy from utilizing seaborne lines of communication, supply, and power projection. Interdiction has both strong and weak forms. The strongest form, of course, is the blockade - which deigns to screen all (or nearly all) ocean traffic to the target country. While a true blockade requires essentially unrivaled naval supremacy, there are weaker forms of interdiction, ranging from privateering (a sort of legal form of piracy common in the early modern era) to submarine operations against merchant shipping.

In short, one can argue that despite the enormous diversity of forms that naval warfare has taken, with astonishing evolution in both the tactical and physical aspects of the warship, navies throughout history have essentially attempted to perform two basic tasks: use the sea as a medium to nimbly and effectively project fighting power towards the land, and deny the enemy the free use of the sea. The cinematic clashes between the main bodies of surface fleets of course have their own tactical logic and intriguing dimensions, but they always support one (or both) of these goals.

One other brief conceptual note worth mentioning is that, rather, obviously, naval operations are both extremely capital intensive and by extension highly fragile. We are of course perfectly used to this notion in the modern age, where shipbuilding programs cost many tens of billions of dollars - the total cost of America’s new Gerald R Ford Carrier class is well over $100 billion, for example. The cost barrier to naval power is not, however, unique to the modern world. Indeed, it seems that it has always been true that navies are far more costly than armies.

Warships are expensive and intricate engineering products, subjected by the ravages of the sea to costly maintenance, and they require specialized (and thus expensive) expertise to both build and operate. In the First Punic War, Rome and Carthage both bankrupted themselves attempting to fight what amounted to a naval war of attrition - by the end of the war, Rome had to finance shipbuilding by squeezing the aristocracy for donations.

Furthermore, the specialized nature of naval engineering often prevents a simple conversion of aggregate national wealth to combat power. For example, at the beginning of the 20th Century Imperial Germany was unable to achieve its goals of pacing British shipbuilding, despite astonishing levels of economic growth and enormous spending on the navy. Between 1889 and 1913, Germany’s GDP grew three times as quickly as Britain’s, and Germany became the 2nd largest industrial economy in the world (behind only the United States). Despite these advantages, Britain’s long-established and vast shipbuilding capacities prevented Germany from achieving its force generation goals relative to the Royal Navy.

In short, the sea is an arena of high risk and high reward; it compounds the usual frictions of war with the added complication of intricate engineering and navigational problems. The enormous expense and the vast (and often highly skilled) manpower required to compete in high intensity naval operations by extension means that navies tend to be more fragile than armies - that is to say, vulnerable to decisive defeat and less able to recuperate fighting power. But this very fact has made battle a decisive instrument in the history of the ocean. The navy that can gain supremacy by crushing the enemy in pitched battle will generally keep it, and thus hoard its privileges thereafter. War on the water can be won or lost in a day, or an afternoon, or an hour, in an undulating foam of blood and wood.

Early Warships and the Birth of the Trireme

Naval warfare has gone through four major definitive eras in warship design, and a fifth is now being born. For most of human history, the basic design of the warship was some variation of the Galley - which is defined primarily by its reliance on rowing for propulsion. Galleys, in various forms, dominated the seas from the earliest days of archaic warfare all the way until the 16th Century, where they put on a violent closing performance at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. Thereafter, the oarsmen of the galley gave way to the classic Age of Sail, when sailing ships armed with shot and powder became the predominant weapons platform. Sail gave way in the late 19th Century to the short-lived age of the Mahanian Battleship, which combined armor, modern naval artillery, and mechanical propulsion (be it with coal or oil), before the Second World War definitively proved the supremacy of Naval Aviation. The aircraft carrier then became the totem platform for naval fighting power, and has remained so until our own unsettled era, with a bevy of missile systems now threatening to force yet another naval revolution.

This is a skeletal look, of course, and the purpose of this series will be to follow the changes in naval combat through the ages. What we wish to note, however, is that for the majority of our history it was the galley, propelled by hardy oarsmen, that provided the main platform for naval combat. The age of the battleship, for example, lasted scarcely 50 years, and the age of sail some 250. The purpose-built war galley, however, was a dominant weapons system for at least 2000 years, all the way from the Greco-Persian Wars to the early-modern Battle of Lepanto. For literally millennia, men operated rowed warships and fought a particular form of naval combat that did not radically change in all that time. Therefore, we will examine the origins of this peculiar and powerful weapons system.

In the beginning, there was no distinction between commercial vessels and warships. Naval combat existed in the bronze age, but it appears to have been largely piratical in nature. Rowed barges, designed for hauling cargo, could just as easily carry a complement of fighting men who would attempt to grapple with their targets (be it an enemy warship or a merchant vessel targeted for raiding) and board it.

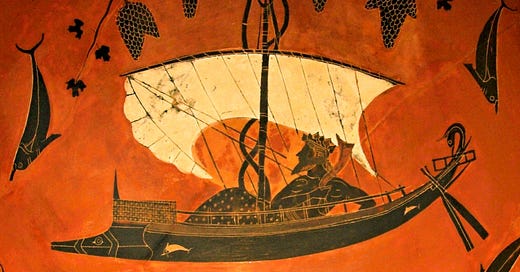

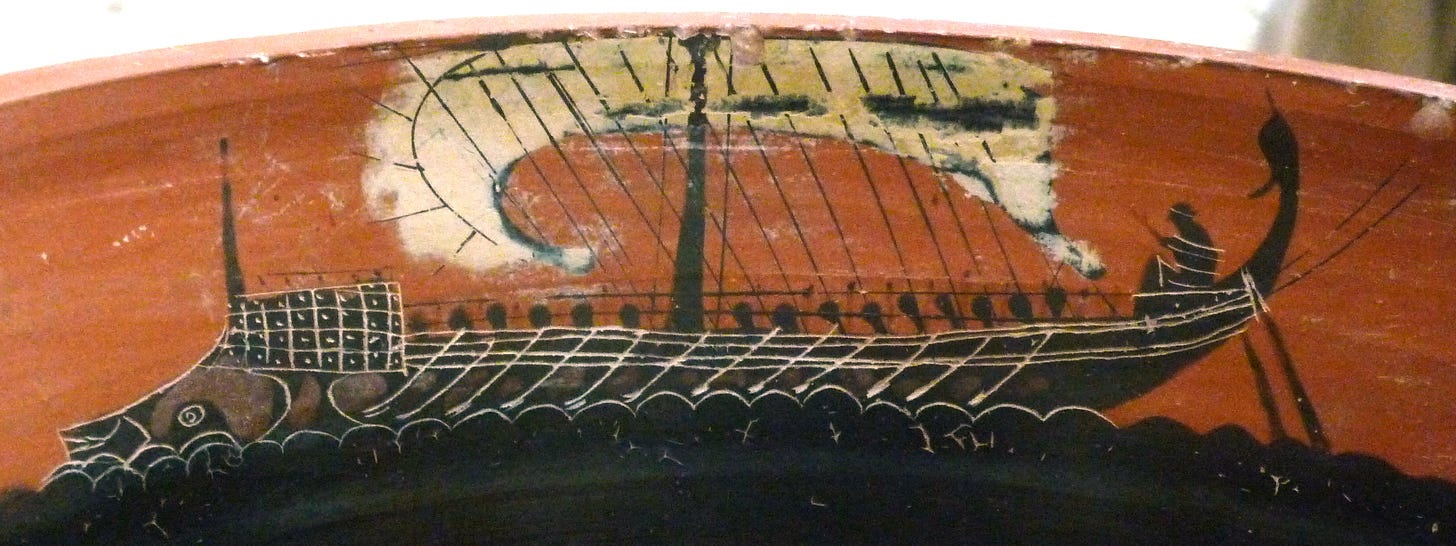

It was not until the 5th and 6th centuries BC that the construction of purpose built warships became prevalent, with varying iterations including the Penteconter - a light warship with a single bank of rowers on each side - and the Bireme, which added a second bank for added propulsion. By 525 BC, the Persian Navy was definitively using the vessel that we know as the iconic platform of archaic naval combat: the trireme.

There remains some debate as to where the trireme was first developed (differing sources have alleged both the frequently oceangoing Phoenicians and the Greeks of Corinth as the first designers), but wherever it was first built, the trireme was a remarkable feat of engineering.

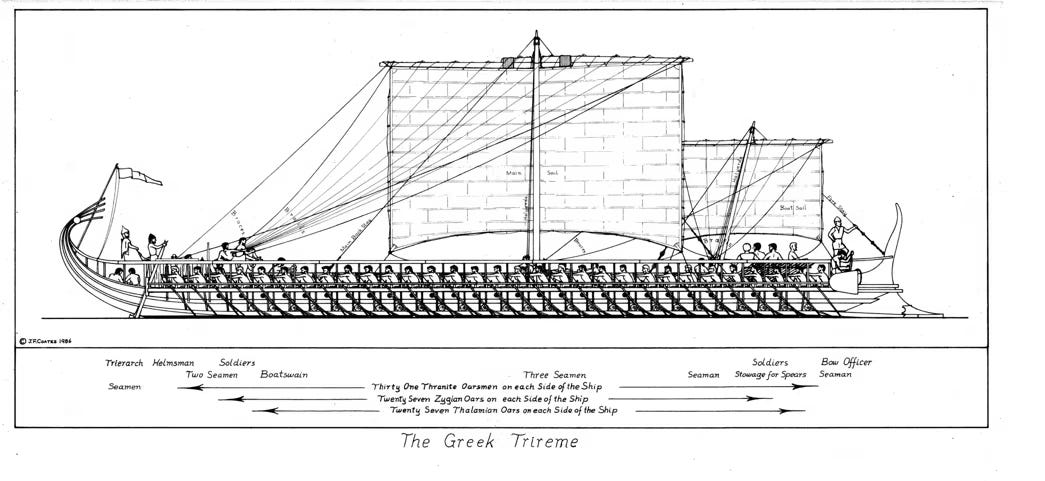

The defining quality of the trireme, of course, was its triple bank of oars, crewed by a standard complement of 170 oarsmen. It may seem fairly obvious that adding more oars would provide more propulsion and speed, but simply adding more and more oarsmen was not an easy engineering task, as they had to be arranged in a way that would provide for efficient rowing without compromising the stability and strength of the ship. Therefore, careful considerations had to be made to balance the combat requirements of the vessel. The ship needed to be strong enough to withstand the impact of ramming in combat, but without being too heavy - both for the sake of speed in combat, and because triremes needed to be hauled out of the water on essentially a daily basis, while a low center of gravity was necessary to keep the ship stable in choppy seas and while attempting agile maneuvers in combat. The trireme seems to have provided the ultimate solution to this difficult optimization problem.

Greek shipbuilders, in particular, adopted a variety of best practices that made the trireme a formidable and sophisticated weapons system. To begin with, the ship was built with an assortment of different lumber, including oak, fir, and pine - these offer varying levels of strength, weight, and absorbency, and they were carefully selected in appropriate ratios to create a light but sturdy hull that could be handled well in combat while surviving the great stresses created by ramming.

As a further method to increase the strength of the hull without unduly adding weight, Athenian triremes featured a massive cable that ran the length of the hull. This cable, called a hypozomata, kept the hull taut via tensile strength - this both reduced the flexing of the planks (preventing it from taking on water) - and strengthened the ship during ramming. The hypozomata was considered so essential to the combat performance of the trireme that they were regarded as something like an Athenian state secret, and it was forbidden to export them or show them to foreigners - though, we should note, the secret did get out and they became a standard component across the Mediterranean.

Finally, the trireme accrued great stability in the water via the arrangement of the oars, which included overlapping oar banks. The lowermost bank of oarsmen sat practically at the waterline, so that the center of gravity remained low. Being arranged near (or at) the waterline and in an overlapping fashion, however, the oarsmen on a classical trireme were essentially rowing blind; they would have had only a bare glimpse at the water through their ports and would have no view of the tip of their oar. Therefore, rowing a trireme effectively was a difficult task that required a high degree of training and group coordination in addition to great physical strength and stamina - particularly when executing precise turns and maneuvers in combat. While a sturdy cloth sail provided some additional propulsion in some circumstances, the square rigged sails of the archaic era had limited value and the primary source of propulsion remained the backs and arms of the oarsmen.

The result of these various engineering features was a ship that was strong yet light. The latter was particular important given the trireme’s need to be hauled out of the water regularly. To economize on space, triremes had very little cargo space and would only have remained on the water overnight in dire circumstances. Furthermore, triremes tended to become waterlogged over time, and therefore needed to be hauled out of the water to dry out. This was thus a vessel intended to be used for day trips, to be beached overnight by the crew.

All in all, then, these were remarkable vessels. Capable of carrying some 200 men (including 170 rowers and a deck crew), they could top 10 miles per hour (more than 8n knots), and a well trained crew could cover more than 60 miles in a day. They could be hauled onto the beach under the power of the crew (a modern recreation estimated than 140 men could pull a trireme onto the beach), had the stability to survive rough seas, could be handled with great precision in combat, and could withstand the impact of ramming an enemy vessel at full speed. As an added benefit, it could be transformed into a powerful amphibious weapons platform with virtually no physical modification to the ship. Simply by reducing the complement of rowers in favor of armed infantrymen, the trireme became a potent troop carrier - slower than the combat configuration, but capable of slithering right up onto the beach and disgorging a complement of warriors, as is described so beautifully in The Iliad.

The classic trireme was therefore among first great feats of human military engineering. It would earn its fame as the central weapons system in one of humanity’s first great wars.

The Great Aegean War

The Greco-Persian Wars (499 - 449 BC) hold a place of pride in the western historical imagination. They are probably the oldest wars that most casual students of history are aware of, and despite their great antiquity they retain a strong emotional pull. Most of the time, the Greeks are viewed as a stand in for “western civilization” writ large, and represent enlightened democratic ideals standing against a despotic Asiatic tyranny. Books on the subject routinely play up this angle - Tom Holland’s “Persian Fire” is subtitled simply: “The Battle for the West”, for example.

Even at a distance of millennia, certain vignettes of the war exert a powerful pull on the imagination. The most famous of these, of course, is the rearguard action of the Spartan King Leonidas at the pass of Thermopylae. It is, to be sure, a cinematic scene, with a small force of Greek heavy infantry valiantly holding their ground for days against an innumerable Persian horde, before being defeated by treachery. Gerard Butler’s washboard abs certainly helped to enrich the scene for us.

There is much that we could say about the Greco-Persian War, and indeed many volumes have been filled on the subject, beginning with the famous Father of History, Herodotus, whose “Histories” center on the war and on the origins of the Persian enemy. Herodotus, as an aside, continues to enjoy a modern resurgence and validation. His Histories remains an extremely engaging and entertaining read, and archeological discoveries routinely prove that he was correct about seemingly phantasmagorical details that were long assumed to be fabrications.

An exhaustive history of these wars is beyond the scope of this piece, to be sure, but we can describe the basic geopolitical shape of the conflict easily enough. Contrary to the popular idea (as presented in the movie 300) that the Persians invaded Greece simply because the Persian King wished to subjugate all human life on earth, the Greeks actually started the war - in 499, several Greek city states including Athens sent troops to support a rebellion in Persia’s Asiatic provinces (on the Aegean coast of modern day Turkey), and managed to sack and burn the regional capitol of Sardis. From the Persian perspective, therefore, the Greeks represented a dangerous foreign backer of internal rebels, and sending troops on an expedition to quell this threat is certainly understandable.

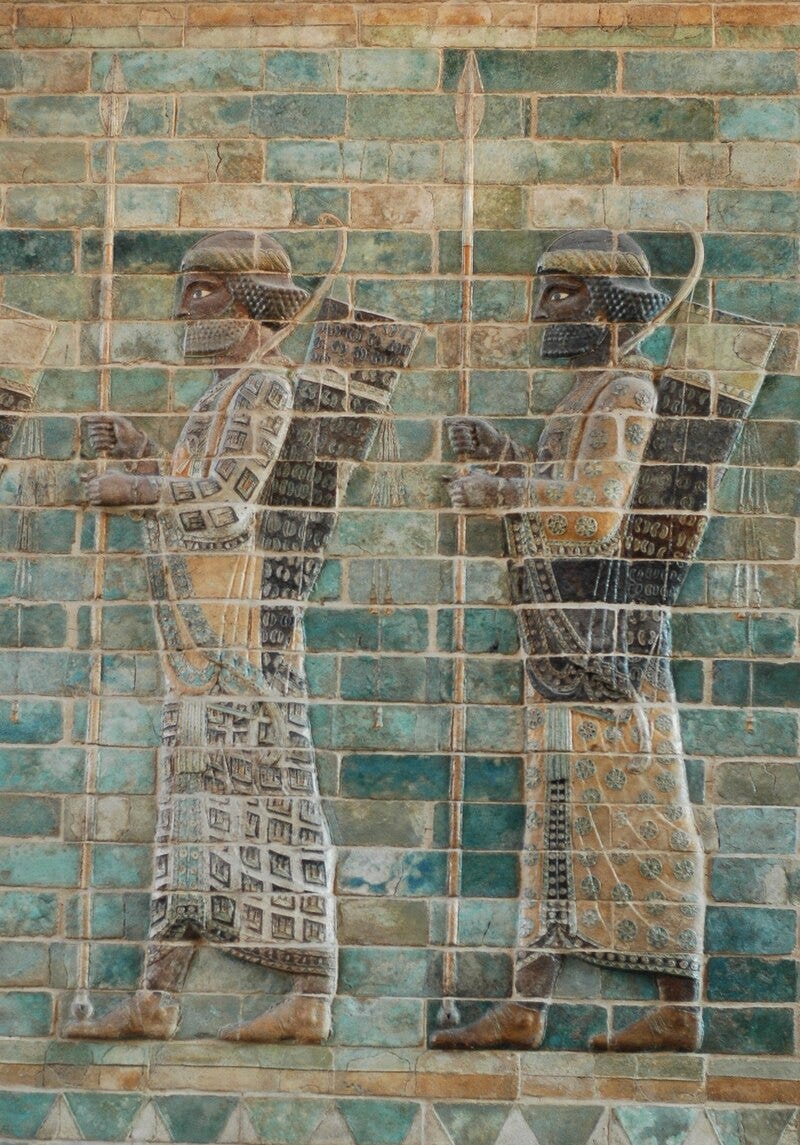

What I wish to emphasize here, and indeed my central argument is that the Greco-Persian Wars were first and foremost a naval war. Military treatments of the war frequently focus on an important Greek advantage on land - namely, that the heavily armored Greek hoplites and their compact formations presented a tactical challenge that the Persians were unable to defeat. There is certainly something to this fact - Persian troops tended to be more lightly equipped (generally using armor and shields made of padded textiles, leather, and wicker) and they found the heavily armored Greek infantry nearly impossible to deal with in close quarters.

Notwithstanding the performance of the iconic hoplites, it was in fact the naval theater that was the decisive dimension of this war, and the Greek victory demonstrated above all that the sea was a decisive theater that could determine outcomes on land. In this sense, the Greco-Persian War was the first great naval war for which we have strong documentation, and the decisive weapons system that saved independent Greek civilization was the trireme.

Indeed, the first phase of the Greco-Persian War took the form of a large-scale Persian amphibious operation against the Greeks. In 490, a Persian task force equipped with some 800 triremes, supply ships, and specialized horse carriers crossed from Anatolia and conducted successful landings on the islands of Naxos and Euboea, sacking Greek cities. This was a potent demonstration of what a powerful state could do with naval power - the sight of hundreds of Persian triremes beaching themselves and disgorging many thousands of infantry must have been shocking. Having successfully “punished” the residents of Naxos and Euboea (for the Persians construed this as a punitive expedition) they sailed on towards Athens.

The famous Battle of Marathon, fought in September of 490, was in form a conventional archaic land battle, with tight formations of infantry deciding the outcome. In its broader conception, however, this was something akin to the 1944 landings in Normandy, with the Athenian defenders attempting to contest a Persian amphibious assault. The Persians beached their fleet at the bay of Marathon, some 25 miles northeast of Athens. Their intention was to disembark the army there and then march it the remaining distance to Athens to conduct a siege, but the Athenians managed to muster their citizen-militia of Hoplites and rapidly march to block the Persian exit from the beach.

The actual battle itself was relatively simple - the outnumbered Athenians (probably some 10,000 Hoplites) formed up a line in a blocking position to prevent the Persians from exiting the plain around the beach. The position was well chosen, because both of the Greek flanks were protected by terrain features - the Bay of Marathon to the right, and a mountainous ridge to the left. This was crucial for two reasons - first, because it prevented the more numerous Persians (who had something like 25,000 men) from simply extending their line and wrapping around the edge of the Athenian line, and secondly because it prevented the Persians from deploying their excellent cavalry. By fighting in the narrow gap between the mountain and the sea, the Greeks managed to secure the only type of fight that they would win, which was a head on, set piece infantry battle.

After the two armies made contact, the line rapidly began to lose cohesion. The Persians had placed their crack troops in the center of the line, and began to make headway against the Greek center, forcing it to steadily withdraw up the road. On both the left and right wings, however, lightly armored Persian troops found it impossible to hold back the heavily armored Greek hoplites, and both Persian wings eventually routed and fled back towards their ships. Rather than immediately pursuing, the Athenian wings then wheeled inward to envelop the advancing Persian center, shattering what remained of the Persian battle line.

Marathon was an important Greek victory, and demonstrated the shock power of the hoplite formations when they could be deployed in favorable terrain. Most accounts of the battle tend to stress the clever envelopment of the Persian center and the powerful weight of the Hoplite lines. It was, to be sure, a clear and decisive victory which put an end to the Persian amphibious operation. What is important for our purposes, however, is the pivotal role of the Persian navy in 490. Using entirely seaborne means, the Persians had managed to successfully raid two Greek islands in the Aegean, then deposit a substantial army within a day’s march of Athens. Then, on the heels of defeat, they managed to extract the bulk of the force - of the some 25,000 Persian infantry present at Marathon, more than 18,000 were able to withdraw to their ships and sail away.

The hoplite phalanx was certainly a formidable tactical expedient, and at Marathon the Athenians found an ideal application, placing their line in an unflankable blocking position. The more crucial strategic dimension, however, was the sea. It was naval power that gave the Persians the ability to project fighting force directly into the Athenian heartland, to supply large armies at great distance, and control the strategic initiative. Marathon was an important defensive action which warded off and forestalled the Persian threat, but control of the Aegean would be the longer-term determinant of victory.

Naturally, therefore, when King Xerxes launched a second, much larger invasion of Greece in 480, the navy was to play a pivotal role. Rather than attempting another punitive amphibious expedition, this was to be a full-scale invasion of southern Greece. Ancient sources claimed that the Persian force numbered in the millions - giving rise to the usual tropes about an innumerable horde of slaves, whose arrows would blot out the sun. While such exorbitant figures are self-evidently ridiculous, modern scholarship does agree that the Persian invasion force was genuinely massive by the standards of archaic armies: perhaps as many as 200,000 men, though many of these would have been camp followers, aristocratic attendants, and support personnel.

Supplying and supporting such a force overland would have been impossible. While the Persians did have a forward base of support on the northern coast of the Aegean in Thrace and Macedonia (which were Persian provinces), it was simply infeasible to run lines of communication and supply overland, particularly in the mountainous and road-poor environs of central Greece. Therefore, from the beginning the plan was to pair the vast and crawling land force with a shadowing naval component, featuring hundreds of triremes and a great convoy of supply ships. The Persian plan of approach envisioned the army marching its way along the coast with regular linkups with the fleet.

Because the Navy was to provide the lines of communication and supply with the Empire, the entire premise of the Persian invasion hinged on the ability to operate in the Aegean - and indeed, as events played out, the Greeks never did have to defeat the massive Persian army. Shattering the navy would instantly render the invasion operationally sterile and, in a word, defeat it.

And so we come back to Thermopylae and the heroically doomed stand of Leonidas and his little Spartan force. The romantic variant of the story emphasizes the idea that the Spartans fought alone - betrayed and abandoned. In fact, the Spartans had powerful assistance loitering offshore. The Spartan defense at Thermopylae was one half of a broader allied plan to block the Persian advance into central Greece. Thermopylae (like the beach exit at Marathon) was a narrow pass between mountain and sea, which offered an ideal chokepoint for Greek heavy infantry, but there was also the sea route to worry about. Given the proven capability of the Persian navy to land sizeable amphibious forces, any attempt to block Thermopylae without naval support would have been suicidal - the Persians would have simply landed a force in the Spartan rear and wrapped the whole thing up neatly. Therefore, a Greek fleet of 271 triremes led by the Athenians was dispatched to block the Persian navy at the strait of Artemisium. This created a pair of simultaneous blocking actions, with both the Persian land and naval elements barred at strategic chokepoints. Far from the story of a lonely and abandoned Spartan stand, their flank was guarded by a Greek fleet, with consistent communication between the two.

The Battle of Artemisium is far less famous than the simultaneous Spartan action at Thermopylae, but it offers a fascinating look at the emerging tactics and battle considerations of classical trireme fleets. And so, at last, we come to this topic. Feel free to berate me for taking 4,500 words to come to the point.

Trireme combat offered three primary possibilities to defeat enemy vessels. These were as follows:

Ramming: Triremes were equipped with sizeable bronze rams on the front prow of the vessel, easily capable of splintering the side of an enemy vessel in a collision at full rowing speed. Because triremes sat low in the water, were not overly seaworthy, and lacked meaningful damage control capabilities, ramming damage to the side could quickly disable a vessel, causing it to list and become immobile. Ramming had to be conducted carefully, with an aim to immediately rowing backwards to disengage - both to prevent a counterattack by the marines on the enemy deck, and to prevent the ram from become tangled or stuck in the enemy hull.

Shearing: By approaching at a partially oblique angle, the prow of the trireme could be used to shear off the oars of an enemy vessel in passing. Even the partial loss of an oar bank would largely immobilize an enemy vessel.

Boarding: Triremes carried a company of marines who could endeavor to grapple with enemy vessels using hooks, ropes, and boarding planks. Because the crew complement of a trireme consisted mostly of unarmed rowers, defeating the enemy’s marines would generally lead to the capture of a vessel.

Thus, archaic naval combat centered on attempting to sink, immobilize, or capture enemy vessels by one of these methods. Matters were complicated by several considerations, however. One of these was the utterly abysmal level of command and control - while rudimentary signal flags and horns did exist, once battle was joined it was virtually impossible to exert central control over the battle. Battles thus tended to revolve around a preliminary plan which could quickly devolve into chaos, particularly as battle lines became disorganized, splintered, or fouled. The ability of individual captains and squadron leaders to improvise and keep their heads in an extremely chaotic, noisy, and terrifying scrum became critical, as did the training and conditioning of the rowers.

By the time of the Battle of Artemisium, the Persians enjoyed not only a substantial numerical advantage (likely nearly 3 to 1 over the 271 ship strong Greek fleet), but also a notable edge in the experience of their rowing crews and captains, with most of the Greek fleet being new construction that had not yet seen serious action.

The Persians (or at least, the Phoenician subjects who crewed much of the Persian Navy) had by this point in time developed a coordinated tactic in battle which the Greeks would later adopt and call the “Diekplous”, which means “through and out”. This is a fascinating maneuver which shows that archaic naval combat was far more complicated than it seems at first blush. It sounds all well and good to simply say “ram the enemy” - but this is not particularly easy because the enemy is also moving about and trying not to be rammed. Furthermore, when fleets approach in battle lines they are arrayed parallel to each other, which makes it very difficult to reach the side of the enemy vessels.

Rather than devolving into a naval dogfight, with ships rowing chaotically about in circles trying to find each other’s soft sides, the Persians utilized the Diekplous. This maneuver called for the front line of the fleet to row at high speed towards the enemy line, with each ship then veering to the side so as to pass through the gaps in the line - shearing off enemy oars if possible, but passing all the way through. Once behind the enemy line, the fleet would wheel around as if to turn towards the back of the enemy’s ships.

The purpose of passing through and then wheeling about was not necessarily to attack the enemy in the rear - it was well understood and expected that the enemy would not simply allow this, but would instead turn their own vessels about to prevent being rammed. It was this very counter-turn that was the point of the Diekplous. As the enemy turned about, they would expose their sides to attack by a *second* line of attacking ships, which would by now be making their own attacking run.

The Diekplous was thus a contrivance that could force the enemy to rotate and disorder his line, so rendering it vulnerable. The attack was not a simple matter of just rowing in and ramming someone in the side - it was important to first disorder and reorient the enemy line to expose the soft targets on the side of the ship. Such a tactic was ideal given Persia’s advantages. Having the more experienced captains and rowing crews, they could feel confident trying to manipulate the less experienced Greeks into disordering their lines. Even more importantly, however, the Persians had more ships, which meant they actually had the capability to form up two separate lines of attack and execute the Diekplous.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.