Among the photographic record of the Second World War, two images in particular became very famous as the iconic representations of the war’s end. The first such photograph, taken on May 2, 1945, depicts a Soviet soldier raising the flag of the USSR over the Reichstag building, with the ruins of Berlin smoldering beneath him away towards a gray horizon. The second picture, taken a few months later on August 14, 1945, depicts an American sailor in Times Square embracing and kissing a young woman in white, against a backdrop of a bright, bustling and optimistic city.

The pictures have very little in common, apart from the rather trivial note that the identity of their subjects is a matter of dispute. The image of the Soviet victory in Berlin is unquestionably apocalyptic, with rubble, smoke, and ruination stretching to the horizon point. It is an image of death. In contrast, “VJ Day in Times Square”, as the kissing picture is known, conveys jubilation and an airy, joyful vitality. It is an image of life.

The duality is, perhaps, fitting. While nominally the end of war is a preeminent cause for celebration, for much of the world 1945 brought little relief. Hundreds of millions were left teetering on the edge of both physical and psychological annihilation amid widespread ruination of their cities and villages, famine, disease, ethnic cleansing and vengeance killing, rape, political revolution, and the nearly unimaginable social trauma brought on by the death of many tens of millions.

Recasting the end of the war as a cause only for jubilation misses the reality of what occurred in 1945. The end of the war was not merely a cozy cessation of conflict, but the complete destruction of two extremely powerful empires - one German and one Japanese - by way of military action. Simultaneous with these two geopolitical executions, a new Empire was born: a Stalinist empire, ruled from Moscow, anti-Capitalist in orientation, built astride an astonishing military-security apparatus.

While it is obvious to us that by the first weeks of 1945 German defeat had long since become an inevitability, the actual task of finally eliminating German armed resistance was fantastically bloody. In the latter half of 1944, the German field armies in the east still fielded more than 2.5 million men, who continued to fight fanatically in many untenable circumstances. Red Armed KIA in the final year of the war numbered in excess of a million. This was a war that ended with a bang, not a whimper.

Hitler made many promises to the German people, and kept them with various levels of success. But there was one promise that he would fulfill in totality. He had always insisted that whatever happened, the “shame of 1918” - Germany’s surrender in the first world war - would not be repeated. In that war, the German army had capitulated while it was still in the field - and not just in the field, but on occupied French territory. Germany lost the first war without its territorial integrity being breached or its army destroyed. That indignity would not occur again. Instead, the Wehrmacht would fight to the death and try to drag the enemy to hell with it in an orgy of phantasmagorical violence.

Roundup in the Ruhr

By the time 1945 dawned on war ravaged Europe, the material state of the Wehrmacht had fallen to unthinkable lows. 1944 had seen the Germans adopt new methods to cover their soaring losses (particularly after the concurrent losses in Operation Bagration and the Falaise Pocket), with the formation of Volksgrenadier divisions. These were a new type of infantry formation designed for close-in positional defense, usually short on heavy weaponry but liberally equipped with submachine guns and man portable antitank weapons. At the time of their introduction, the Volksgrenadier divisions could be seen as a manpower economizing expedient and an ominous sign of collapsing German fighting power - but within a few short months, they would come to seem like a luxury.

After 1944’s stopgap solution of the Volksgrenadier divisions, 1945 would be the time of the Volkssturm - the “people’s storm”. Unlike the Volksgrenadiers, who were at least regular army formations with standardized equipment, the Volkssturm units were barely trained militia units made up of old men, young boys, invalids, civil servants, and any otherwise warm bodies that the Germans could scrounge up. Utterly unsuited for any combat tasks beyond urban brawling, the militia units of 1945 represented the fraying logic of German strategic thinking. At this stage in the game, the premise of Germany’s strategy had now drifted fully into the realm of nihilistic delusion: the idea of the Volkssturm was to make the final conquest of Germany so costly (via the fanatical resistance of the entire population) that allied morale would crack - win a war by making the enemy tire of killing you.

With the Wehrmacht struggling to hold a coherent line and Volkssturm trash units being hastily raised in the rear, Germany’s situation could not have contrasted more sharply from that of its adversaries. While the Red Army had by now mastered its particular form of sweeping operations, on the western front the Germans faced an American Army that was, by all rights, the most liberally equipped and mobile fighting force in history. Fully loaded with armor, half tracks, and self propelled artillery, supplied by truck lift, and protected by an overawing umbrella of air power, the US Army could hit harder and move faster than anybody.

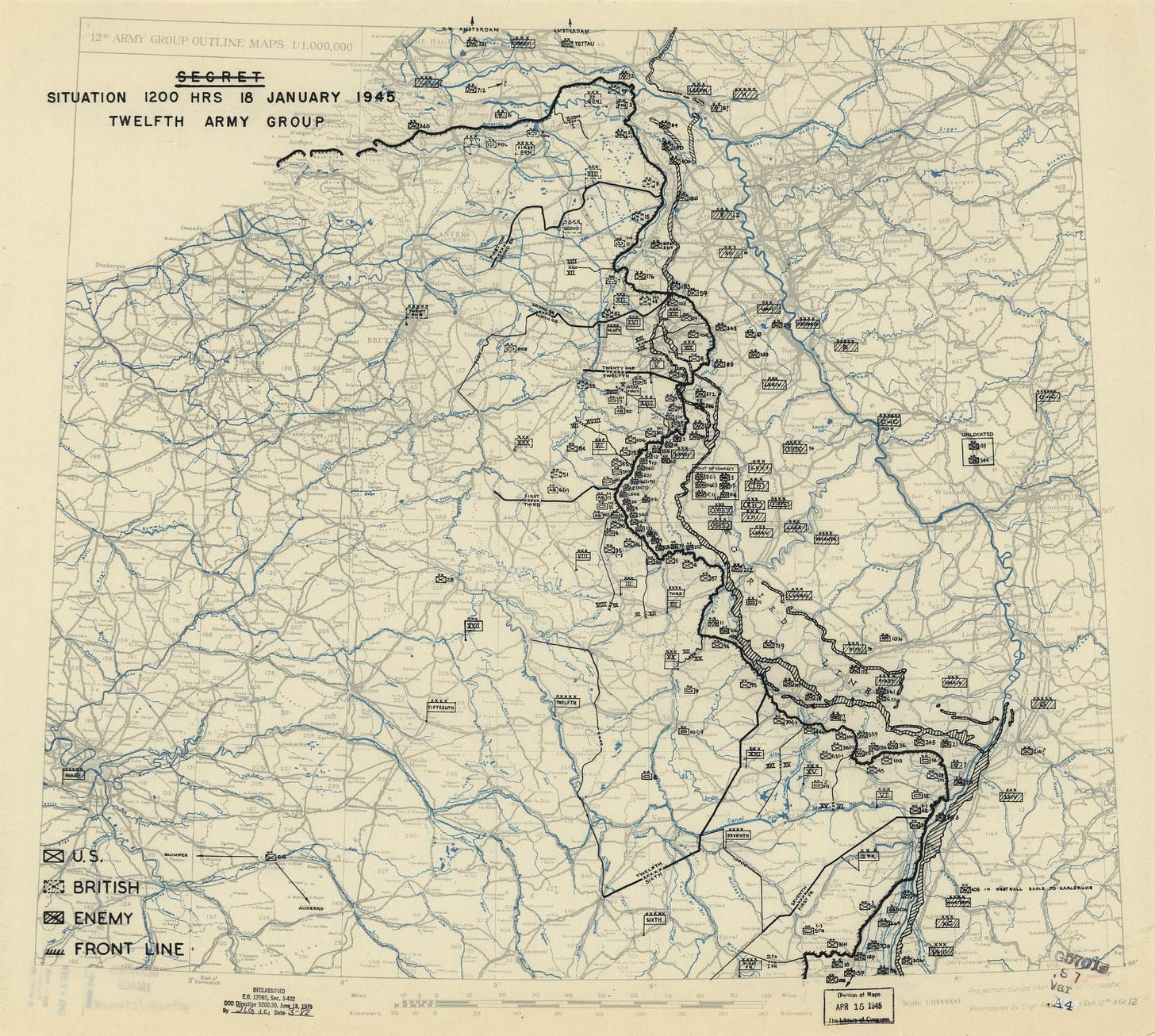

This growing asymmetry may have seemed to be a poor consolation to the nearly five million men in the great allied force bearing down on Germany. For all their material advantages, the going was slow and a series of tremendous obstacles seemed to remain in their way. Much of January, 1945, was spent correcting for the great German winter offensive (the Battle of Bulge), grinding away the German salient and preparing to renew the push eastward. But even after foiling Germany’s last attempt to retake the initiative, the allies faced a series of features greatly favorable to the defense.

First, they would have to grind their way through the Rhineland - the densely populated region west of the Rhine, characterized by rolling, hilly topography - after which they would at last come up to the Rhine itself - one of the world’s great river barriers. This promised a complex breaching task which would require intricate planning and preparation and a good deal of tricky combat engineering. Finally, having crossed the Rhine the allies would find themselves coming upon Germany’s great Ruhr industrial region. This was (and is) one of the world’s great urban agglomerations - home to millions of civilians, dozens of interlinked cities, and vast factory complexes. Even a dying German army could turn these obstacles into dangerous defensive positions, and the Ruhr region in particularly threatened to become (as one historian has put it) a “Super Stalingrad”, obliging the allies to take tremendous casualties digging out the Germans in a sprawling urban battle.

The Germans were on the run, bleeding, dying, but clearly dangerous, particularly fighting behind a major barrier like the Rhine or defending their own cities. The allies certainly understood this, as the Germans had on many occasions in 1944 showed that they were still more than capable of fighting a deadly positional defense - take, just for example, the some 40,000 allied casualties suffered in a multi-month attempt to clear the Germans out of the Hürtgen Forest, or the 50,000 losses suffered by Patton’s 3rd Army in their assault on the Lorraine region. Still over 300 miles from Berlin, with major German formations in the field on accommodative defensive ground, there was every reason to believe that 1945 would bring long, hard fights with high casualties.

Then, in an instant, the clouds cleared and the allies could see daylight ahead.

The capture of the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen by American forces in March 1945 is one of the more famous moments of America’s war - a seemingly impossible stroke of good fortune. The town of Remagen - an otherwise idyllic little burgh on the west bank of the Rhine, home to perhaps 18,000 people - almost seems to exist purely for the purpose of river crossings by armed bodies. The town had its inception as Roman fort, built just upstream of the first bridge ever built over the Rhine - a timber structure erected by Julius Ceasar’s forces in the long past. Millenia later, during the first world war, Remagen was selected for the wartime construction of a new bridge designed to improve rail connectivity between Germany and the western front. This bridge, built between 1916 and 1919 by POW laborers, was named after General Ludendorff, and featured a pair of rail lines and a pedestrian catwalk. It was this bridge that elements of the US 9th Armored Division (a constituent of General Courtney Hodges’ 1st Army) were amazed to see as they rolled up on the approach at Remagen on March 7.

Finding an intact bridge over the Rhine was no doubt an amazing stroke of good fortune for the allies. When General Hodges relayed the good news to his superior, General Omar Bradley, the famous response from the latter was “Hot dog, Courtney! This will bust him wide open!” - the “him” in reference being Eisenhower.

The general interpretation of events is that the Germans were caught unable to make good their escape across the river in time, and the Americans by a stroke of good fortune managed to capture a bridge before it could be destroyed. But this misses the most important element of the story. The Bridge at Remagen was not a story about happy luck, but an operational progression stemming from German lethargy, strategic mistakes, and immobility, and the corresponding American powers of maneuver.

More to the point, when the 9th Armored Division found the Ludendorff bridge intact, the Germans were not defending from behind the Rhine, or even attempting to retreat over it. They were instead fighting hard on its western bank, attempting a positional defense of the Rhineland. The river was not being used as a defensive barrier, but was instead still a geographic feature in the German rear area. On March 7th, when the status of the bridge was discovered, the Wehrmacht had no immanent plans to retreat across the river - an operational decision that in itself would have been immensely complex and required the careful withdrawal of hundreds of thousands of men.

Thus, rather than catching a retreating enemy before it could scamper across the river, the 9th Armored Division had advanced up a seam and gotten into the rear area of an enemy that was still trying to defend a vast and densely populated region on the river’s west bank. Understanding this difference changes the whole sheen of the story: it was not dumb luck that let the Americans reach the bridge, but the foolish German decision to fight a positional defense on the river’s far side against an enemy with vastly superior mobility.

The sequence of events following the March 7 discovery of the Ludendorff bridge present a nearly idealized window into the end of the Reich. The approaching Americans found nothing like a prepared defense, no vast force prepared to defend Germany at the Rhine. Instead, they found a sleepy Remagen and a bridge defended by a rear area force (a mix of infantry, Luftwaffe anti-air crews, and engineers commanded by General Joachim von Kortzfleisch) with orders to guard the bridge or - if necessary - blow it.

The sudden approach of the Americans seems to have caught the Germans largely by surprise. In a scrambled attempt to establish a blocking position on the west bank of the river while wiring the bridge to blow, the Germans failed at both tasks. American tanks managed to rush the bridge in short order - Remagen, again, being considered a rear area had virtually no antitank barriers, mines, or established firing positions. A last minute attempt by the Germans to blow the bridge resulted in a moment of high drama, with the bridge rattling and momentarily vanishing from view in a cloud of smoke. Fortunately, the cloud dissipated to reveal the bridge intact, with only minor damage to one of its pedestrian catwalks, owing to problems with the untested wiring and insufficient explosives.

At this point, the savvy reader may wonder why the Germans had made no preparations to destroy the bridge - even as a contingency - until there were American tanks on approach. The answer lay in an incident from the previous October, when a bridge in Cologne was brought down after an explosive satchel was accidentally detonated. A furious Hitler had court marshalled the responsible officers and instituted new rules which stipulated that bridges could not be wired for demolition unless there were allied forces within five miles - furthermore, a bridge could not be blown without written orders from the chain of command on the scene. Thus, in anger over the premature demolition of one bridge, Hitler had made it nearly impossible for later bridges to be destroyed on time. As it turned out, strict adherence to the new policy would not save the command staff at Remagen - a week later, on March 14, four German officers would be summarily executed for “allowing” the Americans to capture the bridge.

In the following weeks, the Germans would throw a whole host of weaponry at the Ludendorff Bridge, trying to bring it down as the Americans relentlessly pushed forces across to the east bank of the Rhine, flooding their new bridgehead with fighting power. The Germans threw the proverbial kitchen sink at the bridge, firing at it with all manner of artillery including the 60 cm heavy siege mortar, attacking it from the air with trusty Stuka dive bombers, lobbing rocket propelled 380mm mortar rounds from Sturmtiger assault guns, and even shooting a V2 ballistic missile (which missed by many miles). The cumulative damage did finally succeed in forcing a collapse in the span, and on March 17 the Ludendorff Bridge finally tumbled into the Rhine, but by that point it was too late - US Army Engineers had already capitalized on the crossing and erected a host of pontoon bridges, providing a solid link to the bridgehead.

This was the late war Wehrmacht in a nutshell: a whole slew of powerful and advanced weaponry (available in small numbers), officers being executed for capricious reasons, critical infrastructure defended by untrained militia and old men. Most importantly, however, the Germans were now on the verge of an operational annihilation of their own making. The foolish decision to defend the Rhineland to the end, combined with the wastage of much of the remaining Panzer force in the Battle of the Bulge, had left the Germans flat footed, exhausted, strung out on the wrong side of the river, and unable to counter the unexpected American lunge over the Rhine.

For the Americans, however, the sudden crossing of the Rhine opened the door to one of the biggest operational coups of the war. With Hodges’ First Army now building a powerful force in its bridgehead across from Remagen, the Germans began a hasty redeployment to defend east of the river, with Model putting his 5th Panzer Army in place to block the Ruhr industrial region, and 15th Army attempting to block up Hodges’s bridgehead. Despite the generally parlous state of the Wehrmacht by this point, the prospect of bashing through these two armies in a dense urban region like the Ruhr was not a pleasant one, and it brought the distinct possibility of huge American casualties in the war’s closing act.

Fortunately, Eisenhower was not aiming to fight through the Ruhr, but to encircle the entire thing. He already had the base of one pincer in place, with Hodges’ 1st Army now preparing to break out of its bridgehead at Remagen. The other pincer was prepared with the accelerated launch of Operation Plunder, which got General William Simpson’s 9th Army over the Rhine near Wesel, some 80 miles to the north, on March 23. Plunder took no chances with the crossing, and featured a massive parachute drop on the German side of the river to ensure the successful seizure of a bridgehead.

In short, Eisenhower now had two powerful American armies over the Rhine River, on both the northern and southern peripheries of the Ruhr region. It was time to roll.

While Simpson was getting his forces sorted after crossing the Rhine, it was time for Hodges to punch out of his bridgehead. The density of forces in the Remagen bridgehead was astonishing - Hodges had packed three overweight corps, a fully mechanized powerhouse brimming with armor, trucks, and self propelled artillery. An unexpected clearing of the skies, which allowed American tactical aviation to blanket the roof and drive the Germans off the roads, only put the cherry on top.

Hodge’s breakout from Remagen began on March 25, and already by the 28th his lead elements were more than 80 miles to the east, ready to loop north behind the Ruhr. The lead American formation by this point, spearheading the great pincer, was an armored column under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Walter Richardson - a constituent force of General Maurice Rose’s 3rd Armored Division.

Task Force Richardson’s job was to roll up the highway to the cities of Paderborn and Lippstadt, where they would link up with elements of Simpson’s 9th Army - completing the encirclement of the entire Ruhr region. Unfortunately, at this moment a scene of genuine drama unfolded.

The official US Army History (the famous Green Book series) describes events this way:

The longest delay for Richardson’s column developed in Brilon, twenty-five miles short of Paderborn, where, as Richardson and an advance guard pushed on, someone among the tank crews discovered a warehouse filled with champagne. When the tanks finally caught up with their commander, the actions of many of of the crewmen provided disconcerting evidence of their find.

Task Force Richardson at last halted around midnight fifteen miles short of Paderborn… Although still short of the objective, Richardson and his men had covered forty-five miles at a cost of no casualty more severe than the headaches some men suffered from too much champagne.

Unfortunately, the following morning Richardson’s armored column - with its crews still hungover - bumped directly into a battlegroup that had just deployed from a nearby SS training facility, armed with nearly sixty heavy panzers including tigers and panthers. In the confusion of the ensuing fight, General Rose (who had come up to supervise the assault) was killed when his staff car ran into a column of German tanks.

The tragic death of an esteemed and widely respected general notwithstanding, the Germans could not stop the avalanche. Task Force Richardson was only the spearhead - more and more American tentacles shot up the roads, bypassing the SS defenses and linking up with elements of the 9th Army at Lippstadt on April 1. It was Easter Sunday.

The Americans now had most of the remaining battle worthy formations of the German western front rounded up in a pocket overlaying the cities of the Ruhr - a trap some 30 miles wide. Trapped in the Ruhr Pocket were hundreds of thousands of German troops (most of Walter Model’s Army Group B), thirty generals, and millions of German civilians.

The reduction of the Ruhr Pocket (like its encirclement) was achieved with remarkable speed - two weeks, to be exact. Wary of the danger that the Germans could pose in a positional, urban defense, the American approach was simple, and they opted to simply flatten with artillery fire any position that fired back at them as they approached. The US Army history of the battle simply states that artillery shells were “unrationed”, and notes that the XVI Corps, for example, fired exactly 259,061 shells during the fourteen day effort to liquidate the pocket - and there were three other corps involved in the struggle.

Amid this maelstrom, German civilians in the pocket reacted in a muddle of confusion and terror. While the regime urged them to fight to the death, few were enthused by the prospect, and there was a great deal of proactive effort by civilians to surrender their homes and towns before the Americans were provoked into shelling them. A difficult coordination game now came into play: when to surrender? Raise the white flag too early, and you might find yourself shot for cowardice and defeatism by a German officer. Surrender too late, and you might hear the whistle of inbound shells. Even surrendering is not always easy.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.