It makes no difference what men think of war, said the judge. War endures. As well ask men what they think of stone. War was always here. Before man was, war waited for him. The ultimate trade awaiting its ultimate practitioner. That is the way it was and will be. That way and not some other way.

~ Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

It is undeniably true that war is among man’s oldest preoccupations. The evidence is abundant that war is essentially as old as mankind’s political life, predating cities and sedentary society. It seems that man took recourse to organized violence almost as soon as he grew to a socio-political pattern of life, and from that early period much of human political and technical innovation was spurred on by the relentless drive to fight and win.

Almost as soon as war graduated past its tribal phase, it seems that man stumbled upon his next great tradition - not a tradition quite as old as war, but nearly so. The oldest battle for which we have recorded details on battlefield movements (thus the oldest battle that can be reconstructed in some level of detail) was the Battle of Kadesh, fought between the Egyptian Pharoah Ramesses the Great and the neighboring Hittite kingdom. The climax of this battle was a heroic and audacious maneuver by Ramesses, who led a battlegroup of charioteers on a ride around the battlefield to attack the Hittites on the flank.

It thus seems that for nearly the entire history of warfare (which is to say the history of man), armies have been attempting to get a powerful grouping of combat power mobile, move it to the enemy flank, and attack it immediately. Such maneuver sits at the nexus of those two powerful coefficients of battle - rational calculation and emotive aggression. Warfare constantly mediates between these two, balancing the strategic benefits of planning with the initiative and vigor of instinctive aggression. Maneuver sits at the crossroads and harnesses their powers synergistically, promising victory through initiative, decisiveness, and aggression.

Yes, armies have been lusting for the enemy flank for millenia, but technical factors often frustrate their efforts to get there. Maneuver waxes and wanes as a battlefield expedient, at times kneecapped by various technical or material constraints, be it shortcomings in logistics, command and control, or the protection of assets on the move. Operational maneuver in particular has frequently gone through long periods of technical sterility. Today in Ukraine, the ability of both combatant armies to strike staging areas and troop concentrations has forced a re-emphasis on dispersion and concealment. With maneuver once again at a crossroads in Eastern Europe, we can conclude this series by considering maneuver in its eternal relation to the military arts writ large.

Trapped in Theory

Having made a long an arduous walk through the timeline, we see disparate instances of the military art splattered like a temporal collage of violence. What is it that unifies the body of examples? Is there a conceptual connection between the oblique order of the Thebans at Leuctra, the Mongol flying columns in Persia, Napoleon’s corps movements, and the Wehrmacht’s panzer package? Is there a unifying theory of maneuver at all?

Maneuver, in the simplest terms, is the use in warfare of movement relative to the enemy to gain some advantage. However, as in all areas of human endeavor, definitions themselves can become battlegrounds. Maneuver has meant different things in different ages, and in the modern age has become the subject of self-conscious debate - as, for example, in the case of the US Marine Corps’ internal wrangling over the “Maneuverist” school of warfare. It is easy to get bogged down in these arguments, or to come away thinking that “Maneuver”, like obscenity, is something that we cannot define, but we know it when we see it.

Modern sensibilities of maneuver - particularly those of the American military - are in fact almost unrecognizable from earlier concepts. In particular, modern theories are intensely battle-centric and focused heavily on the use of tempo and initiative to disrupt the enemy’s ability to process and fight. Furthermore, in the modern parlance, maneuver is held to be essentially the opposite of positional fighting; the former is mobile and decisive, the latter is static and incremental. Such a schema would have been alien to the great generals of the early modern era. In the era of early modern warfare “maneuver” meant something very different, being both distinct from recognizably active battle and intrinsically tied to position, rather than being opposed to it.

An example would likely help, and the best comes from the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). A little studied and little appreciated war today, this was nonetheless a war of colossal import and great military interest - fought (at the risk of fantastical reductionism) to determine the balance of power in Europe between the Hapsburgs and the French, with the British backing the Hapsburgs to contain an increasingly powerful France from establishing continental hegemony.

In any case, the military aspects of the war are fascinating, because cosmetically it would appear to be a static and attritional conflict. Battles were linear, head on affairs (as was typical in the era of early musketry), and the front lines (which largely ran through modern Belgium) were dominated by complex networks of fortresses and earthworks. When viewed at satellite scale, this looked like a more primitive variation of World War One, with small territorial changes, powerful fortifications, and an apparently positional-attritional character.

In fact, the War of the Spanish Succession featured three of history’s most gifted generals, including one from each of the primary combatants: Prince Eugene of Savoy for the Hapsburgs, John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough for the British, and Marshal Claude Louis de Villars for the French (shorthanded simply to Prince Eugene, Marlborough, and Marshal Villars). All three are recognized by historians as supremely talented commanders, with sensibilities that they would have clearly defined as “maneuverist.”

The essence of campaigning in the WoSS was a complex series of marches and countermarches designed to lever the enemy out of position or create otherwise favorable circumstances for positional improvements. In such an operating, environment, however, the lines between maneuver and positional fighting were easily blurred. Let us take two notable examples from the career of the Duke of Marlborough, which usefully illustrate the issue.

By 1711, after a decade of war, the anti-French alliance had slowly but surely squeezed the French out of their positions in the Spanish Netherlands (as Belgium was rather confusingly called at the time), pushing the lines of contact into Northeastern France. Despite several years of setbacks, the French could feel confident in their position - the frontier was guarded by a well prepared defensive line, immodestly called the “Ne Plus Ultra Line”. The line was essentially a defensive belt of rivers (many of which had been strategically dammed to raise water levels), earthworks, fences, and fortresses, with Marshal Villars prowling behind with the French Field Army. Villars felt, and not without reason, that the line was essentially impenetrable. His confidence was boosted by the unstable political position of Marlborough, who faced growing opposition back home in Britain. Villars felt that he was fighting from a position of great strength against an adversary who was under political pressure to take risks.

Marlborough, however, contrived a brilliant scheme to pierce the Ne Plus Ultra Line without firing a shot. Knowing that Villars’ intention was to follow him laterally across the line to contest any attempt to cross, Marlborough moved west towards the fortress at Arras. Villars dutifully followed him. Marlborough then made a great show of preparing to offer battle - sending out screening cavalry detachments in full view of the enemy, and riding out with his staff to survey the terrain. French sentries observed the Duke gesturing with his cane, pointing out various terrain features and objectives to his officers. Villars implicitly believed that Marlborough would offer battle in the coming days, and sent a letter to King Louis XIV informing him that he had “brought Marlborough to his Ne Plus Ultra”.

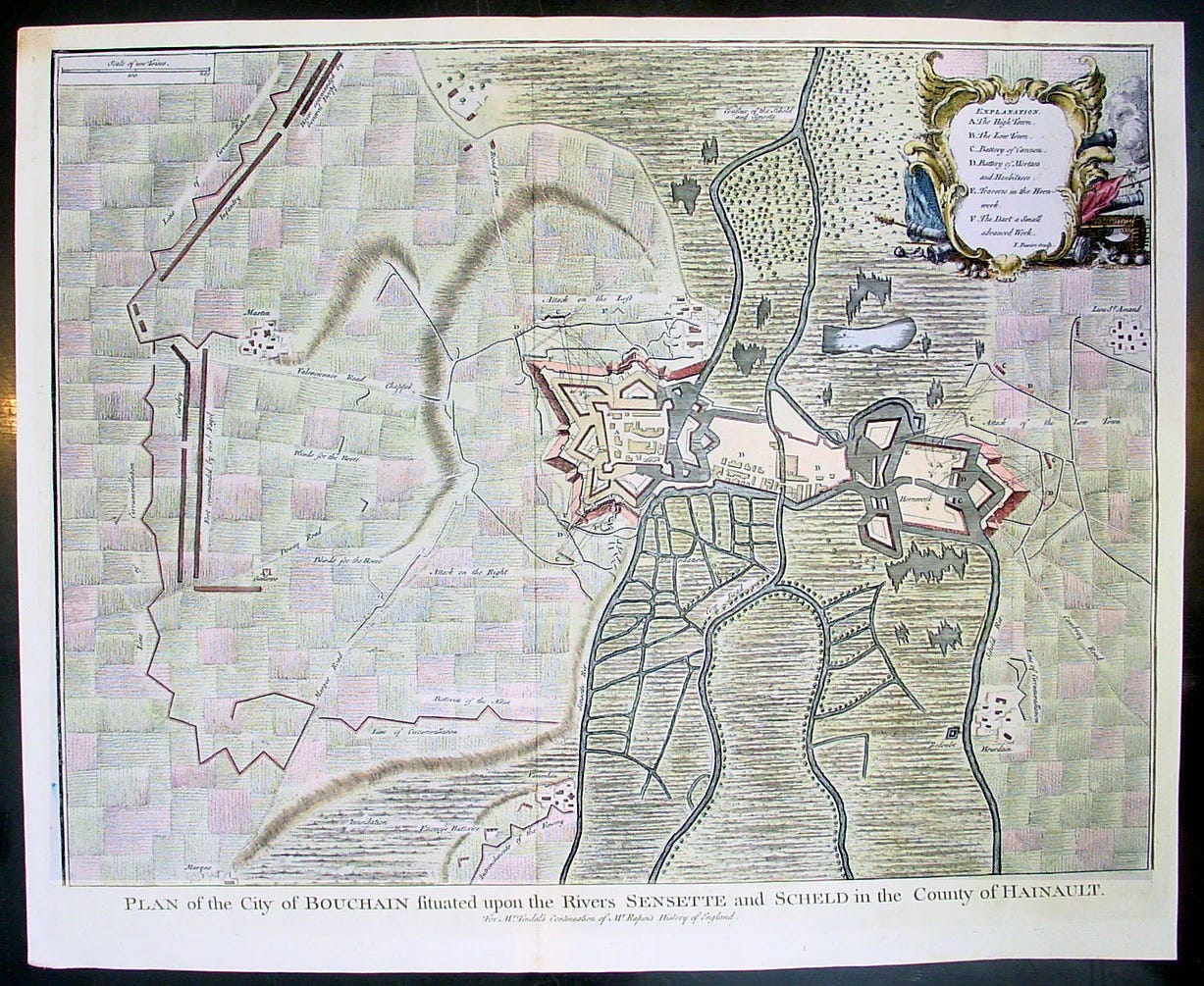

The order came down: “My Lord Duke wishes the infantry to step out." Marlborough would not offer battle - instead, he clandestinely struck camp as night fell, and began a forced march back towards the east at top speed, reaching a pre-designated crossing point over the Scheldt near the fortress at Bouchain, linking up with engineers and artillery that had been secretly positioned in wait. It was about 9:00 in the evening when Marlborough began his rapid shuttle to the east; Villars got wind that the British had gone at 2:00 AM, and though he immediately decamped in pursuit, that five hour head start was more than enough. Marlborough’s forces covered over 30 miles in about 19 hours, and managed to move the entire body over the Ne Plus Ultra Line without a fight.

This was certainly an impressive and effective operational contrivance by Marlborough - drawing the main body of the French field army out of position with a feint towards Arras, then flying back up the road under the cover of darkness to cross the river lines near Bouchain. What seems incongruous, however, is that Marlborough used this maneuver to position himself for a siege of the Bouchain fortress. Having crossed the river lines and penetrated the French position, he set his men to work building fortifications of his own. Most importantly, Marlborough’s men built a pair of long entrenchments and earthworks running back to the rear, creating in effect a protected lane of supply and communications which allowed them to haul up the ponderous and vulnerable siege train, with the enormous cannon required to reduce the Bouchain fortress.

What relation did Marlborough’s Bouchain operation have to “Maneuver”, as such? In the modern scheme, the fit is not immediately obvious. None of the favored motifs about tempo or aggression particularly apply. Marlborough did not “open up” the front or create a state of mobile operations. Rather, he created a window of opportunity for himself to seize an important position. The usual dichotomy of war being either mobile or positional breaks down here; maneuver for Marlborough is not an alternative to positional combat, but an enhancement to it which allows him to seize an advantageous position.

Another campaign of the Duke’s, however, offers an interesting counter-example, that being the famous 1704 march to the Danube and the subsequent Battle of Blenheim. The strategic conception was fairly straightforward: the French began the 1704 campaigning season by linking up with their Bavarian allies for an offensive into the Hapsburg heartland with the intention of threatening Vienna and forcing the Hapsburgs to negotiate, thus splintering the anti-French alliance. Marlborough, who had been wintering in the Netherlands, made the risky decision to march a portion of his army all the way to southern Germany to counter the French offensive.

Marlborough’s march up the Rhine has always drawn very high (and well deserved) marks from historians, for a variety of reasons.

The distance traversed was monumental for the day, with Marlborough’s 20,000 strong force covering some 300 miles by foot in a month. Despite the enormous distance covered by this “scarlet caterpillar”, as the long columns of redcoats were described, they arrived in the southern theater in superb fighting condition, much to the astonishment of their Hapsburg allies. This was thanks to extraordinary staff work by Marlborough and his team. The march route was carefully plotted out, and messengers were dispatched on horseback (with bags full of cash) far in advance of the main body to arrange supply depots. Consequently, the Duke’s men would march into various and sundry towns on the scheduled day to find food and livestock fodder waiting for them. Marlborough thus kept his men well fed and minimized their fatigue. He even arranged to have them re-shoed, making an advance purchase to have tens of thousands of pairs of boots manufactured and delivered to Heidelberg, where the army found them waiting in enormous mounds. The precise planning of the march and the regularity of the supply were executed to near perfection.

Furthermore, the strategic redeployment entailed no small measure of risk at both the strategic and the operational level. Decamping for the Danube front left the Netherlands relatively undefended, but Marlborough accepted the hollowing out of this important front, correctly gambling that the French would not be able to exploit his absence. Furthermore, the march itself was perilous, because it necessarily involved moving laterally (that is, across the face) of the French border in marching columns. What this meant was that for an entire month, Marlborough would be presenting his flank to the enemy as he worked his way south. Again, however, the French were not positioned to capitalize.

The rapid and well-executed move to the south succeeded, without exaggeration, in saving the anti-French alliance. Linking up with Hapsburg forces under Prince Eugene, Marlborough and his allies smashed the French at the Battle of Blenheim, destroying much of a large French field army, killing its commander, and completely defeating France’s southern strategy. The victory even succeeded in knocking the key French ally (Bavaria) out of the war. Blenheim is understood as a key turning point in the war which dissipated early-war French momentum.

Marlborough’s 1704 campaign impresses in a variety of ways. He demonstrated a decisive instinct for command along with a bold tolerance for strategic risk, and the staff work in organizing and supplying the long march was truly exceptional. There was absolutely nothing easy or automatic about marching an early 17th century army hundreds of miles away from its supply bases, but Marlborough executed it seamlessly. Then, having successfully redeployed to the south, he fought and won a close run battle against a powerful French force. All the while, he had to manage a politically delicate coalition with the Hapsburgs. This was a classic for the ages.

But what was the relation of the Blenheim campaign to Maneuver as such? While the speed of Marlborough’s movement to the south certainly evokes an impression of maneuver, in fact the campaign was simply a footrace - an attempt to reach the southern theater in a timely manner to prevent Hapsburg defeat. Marlborough did not aim to gain some advantage from movement, but only wanted to reach the decisive theater in time. The Battle of Blenheim itself was a fairly straightforward and linear field battle, with the two armies drawn up in rather classic formation. This was a display of operational mobility, to be sure, but not maneuver.

Thinking about these two operations of Marlborough - the 1704 march to the south, and the 1711 penetration of the Non Plus Ultra Line - we see that maneuver as a concept can be easily misconstrued, in particular with the modern battle-centric scheme and the aversion to positional warfare.

In 1711, Marlborough genuinely did make use of operational maneuver, using rapid lateral movement to shake off Villars and slip across the river line uncontested. In the simplest terms, he used movement to achieve meaningful advantage - however, because that advantage manifested itself in a positional siege, it would seem to be out of sync with the open and battle-centric modern schema of maneuver. In contrast, the 1704 campaign utilized rapid movement, but this was a simple matter of reaching the critical theater, rather than generating some advantage that could be levered into battlefield success.

Having suffered through this long ancillary diatribe about Marlborough, we come to the point. Maneuver and movement are not synonymous, in that some operational movements are not maneuver as such, and some maneuvers do not lead to mobility. Our general conception tends to assume that war is one or the other - position or maneuver, attrition or annihilation - but in fact these concepts can coexist quite comfortably, with maneuver empowering position and vice versa.

In the age of Marlborough, in fact, maneuver generally manifested itself as antithetical to battle, in that it could allow a force to lever the enemy out of favorable positions. For example, we may return to our old friend Marshal Villars - it is easy to feel bad for him after being juked out of position by Marlborough, but in 1712 he would have his own moment of greatness and revenge - with the anti-French coalition on the verge of victory on the northern front, Villars maneuvered his forces through a seam in the enemy positions with an audacious night march, cutting them off from their supply depots and forcing them to withdraw. With one bold maneuver, he unraveled years of coalition gains and set the stage for the compromise peace that finally ended the war.

Warfare in Marlborough’s era is usually described as “limited”, or “positional” in nature, often characterized by agonizingly slow and incremental gains. This was not, however, due to some doctrinal preference for position, but rather due to the logistical constraints of the era. Standing armies had become quite large, with demands for food and animal fodder that made it impossible for them to live off the land. The only way to sustain early modern armies was by assembling enormous stockpiles of food, fodder, powder, and other supplies, and running constant convoys of horse drawn wagons to haul these supplies from the depot to the field army. Given the poor state of European roads at the time, however, the range and speed of these wagon convoys was poor. Thus, the nature of the supply system kept armies tightly chained to their logistical chains and tended to keep them close to their depots, and maneuvering to threaten the links between army and depot was one of the main operational goals of all the combatants. This is why Marlborough’s march to Blenheim was considered so exceptional - it remains one of the only examples of the era where an army managed to operate away from its own supply magazines.

The point here is that for generals like Marlborough or Villars, “maneuver” took on a particular meaning based on the material context of the war. The “limited” and position-oriented nature of their maneuvers was not due to some lack of vision or skill on their part, but deeply entwined with the constraints of the military system at the time.

Maneuver and position only began to separate with the later advent of the Prussian operational sensibilities and the kinetic operations of the Napoleonic era. Napoleon practiced a highly mobile and aggressive form of warfare, but it was not recognizably a form of maneuver as defined by the likes of Villars and Marlborough. To those earlier generals, maneuver was about levering the enemy by manipulating position and threatening crucial lines of supply and communications that connected enemy depots, fortresses, and field armies. Men like Napoleon and Frederick the Great, on the other hand, liked to get after the enemy at top speed and attack him immediately - on the flank, if possible, but frontally if necessary. Napoleon had little time for wriggling his way on to the enemy’s supply lines - he wanted to find the main enemy field army and crush it.

Thus, the concept of maneuver expanded over time. Napoleon did not always use positional manipulation to defeat the enemy. Sometimes - as in the case of the famous Ulm Campaign - he would use a Marlboroughean (is that a word?) form of maneuver, to lever the enemy into surrender, but often he simply attacked frontally in a conventional field battle and smashed the enemy with the superior French tactical package and his own magisterial feel for command.

Modern theorists, like John Boyd, finally offered the conceptual framework to expand the definition of “maneuver” to include the generalship of men like Napoleon and Frederick. The key, according to this American school of thought, is in tempo, speed, and the disruption of the enemy’s ability to process information and make decisions. Napoleon’s operations were a form of maneuver because the French army used its superior speed and agility to disrupt the enemy’s deployment and command.

The American theorist William Lind (a disciple of Boyd), who wrote the self-importantly titled “Maneuver Warfare Handbook” even went so far as to argue that operational maneuver was exclusively about time, speed, and cognitive processing. He noted in that 1985 book that that the Soviet doctrinal guidelines defined maneuver as “the organized movement of troops during combat operations… for the purpose of taking an advantageous position relative to the enemy.” Marlborough and Villars are nodding, but Lind disagreed. Maneuver, he insisted, was not a question of spatial arrangements or position, but mental processing, and maneuver warfare was the art of acting and thinking faster than the enemy.

“But Serge, you onerously verbose rapscallion”, I hear you say. “Why does any of this matter? Is theory really that important? Isn’t this just an obscure debate among historians?” Well yes, I reply, but theory does matter a great deal, because it creates the cognitive architecture that militaries take to war. Armies become trapped in their theoretical animuses, which prime them to view warfare in a particular way. Misinterpreting the past to shoehorn events into a predetermined theoretical framework is often a path to battlefield difficulties or even defeat.

The German officer corps provides a poignant example of this. In the interwar period, the vestiges of the German army did an extensive amount of navel gazing, contemplating where they had gone wrong and how the first world war could have been lost. This period of soul searching reinforced the sense that war had to be fought in a mobile, attacking way - concepts from the the German operational tradition, like Schwerpunkt, Concentric Attack, and the fetishization of mobile operations became ever more deeply entrenched.

When this system worked, it worked brilliantly. German operational sensibilities and aggression carried the Wehrmacht agonizingly close to victory, churning its legs to the end at Moscow, in the Caucasus, and in North Africa. However, during the second half of the war the Wehrmacht increasingly looked like an army trapped in an alternate reality, enslaved to its own doctrine and historical self-conception. The late war history of the Wehrmacht is littered with operational schema that no longer made any sense - counterattacking the beach at Salerno, or the Mortain Gap in Normandy, or drawing up a phantasmagorical counteroffensive through the Ardennes in late 1944.

In the comfort of our hindsight, it is easy to dismiss ideas like “Schwerpunkt”, or “Concentric Operations”, or any of these other buzz words as simply artifacts of history - obscure lexical curiosities for military historians to throw around. They are that, but they were once more. These words and concepts were central to the way that German officers viewed and fought the war. They are splattered across the war diaries of the Wehrmacht and embedded in their orders and maneuver schemes. A unifying theory or doctrine of warfare is important for a military, because it provides a cohering intellectual framework that allows the officer corps to see and interpret events the same way, and thus act in a more unified manner. However, these theories and doctrines can easily become traps when they no longer correspond to the physical substrate of the war, and the events of recent decades have shown us just how fast that substrate can shift.

Maneuver’s Eternal Return

The American military establishment spent the post-Vietnam decades thinking intensely about how to fight a major ground war, particularly in Europe, under peculiar cold war conditions. The fruits of this American reinvention were a reinvigorated training regimen, an array of new weapons systems and vehicles, and a totalizing commitment to agile command and control, strategic use of deep fires, and mobile operations.

Fortunately, the wargaming of the cold war remained an intellectual exercise only, and there was never occasion to test American doctrines and systems against massed Warsaw Pact tank armies. The Fulda Gap remained at peace, and Mikhail Gorbachev opted to unravel the Soviet Union with a series of self destructive political reforms. The bipolar world collapsed, as if spontaneously, into a temporary moment of unipolarity and utter American hegemony, and the American military was left holding an enormous hammer with nothing to smash.

Hence, the Gulf War - an unrivaled display of profligate military supremacy. America’s Desert Storm stands at the pinnacle of the military art; a surgical, almost surreal dismantling of the adversary. America and her coalition axillaries destroyed, in the course of only a few weeks, the 4th largest army in the world, shattering a million man Iraqi army at the cost of fewer than 300 dead among the entire coalition, and a mere 148 Americans. The “kill ratios” were astonishing: something on the order of 70-1 in personnel and 80-1 in armored vehicles. In a sense, it appeared that the United States had “solved” conventional war, winning total victories at near-zero cost.

In hindsight, of course, it was easy to point out all manner of deficiencies in the Iraqi military which betrayed it to be a vast, but overmatched force. Iraqi command and control, morale, training, integration of fires, field grade command, and small unit tactics were exposed as utterly inadequate, and American forces enjoyed critical technological advantages, such as its airborne electronic warfare and ISR platforms, precision guided munitions, and the superlative fire control system on the M1 Abrams tank, which allowed American tankers to trade at exorbitant ratios when dicing it up with Iraqi armor.

It is probably fair to say that American and coalition forces enjoyed decadent advantages in virtually every dimension of combat effectiveness, including the technological, the institutional, and the human. All that being said, however, the Coalition campaign was extremely well organized, and this fact greatly augmented the inherent advantage in combat effectiveness. The situation can be somewhat compared to the German conquest of Poland in 1939 - Germany had insuperable military advantages, but a well designed maneuver scheme allowed the Wehrmacht to leverage the biggest and most overwhelming victory possible.

The Gulf War saw two distinct phases: a strategic air campaign (the first modern air campaign at scale against an enemy with an integrated air defense) and a maneuver campaign. We can consider the characteristics of each in turn.

The coalition Strategic Air Campaign (with over 90% of the sorties provided by American aviation) had a powerful shaping effect, in that it degraded and paralyzed Iraqi capabilities at both the strategic and operational level. Strategic targets included power generation, road and rail infrastructure, government offices in Baghdad, and industrial facilities - closer to the battlefield, critical targets like air defense, command and control posts, strike systems (particularly SCUD missile launchers), and communications were hunted.

The most impressive element of the air campaign, however, was the eradication of the Iraqi air force and air defense. On paper, the Iraqis had a sizeable park of air and air defense assets, with the world’s sixth largest air force (parked in specially built hardened aircraft bunkers), over 100 SAM (Surface to Air Missile) batteries, and an integrated air defense network. The Iraqi air defense net was tied to a centralized command and control bunker which ran on a French-designed computer system called Kari (the French name Irak spelled backwards). A prewar report from the Pentagon described the Iraqi air defense the following way:

The multi-layered, redundant, computer-controlled air defense network around Baghdad was denser than that surrounding most Eastern European cities during the Cold War, and several orders of magnitude greater than that which had defended Hanoi during the later stages of the Vietnam War. The multi-layered, redundant, computer-controlled air defense network around Baghdad was denser than that surrounding most Eastern European cities during the Cold War, and several orders of magnitude greater than that which had defended Hanoi during the later stages of the Vietnam War.

In fact, this was rather overly generous. The size of the Iraqi defense system belied a variety of major problems. First and foremost, Iraqi defense batteries were deployed in a point-defense role, creating clusters of air defense around strategic targets (particularly Baghdad and the invading Iraqi forces in Kuwait) with enormous gaps that allowed easy penetration of Iraqi airspace.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.