The Ship of Theseus is a very old thought experiment, relayed to us by Plutarch in his “Life of Theseus.” In its original formulation, Plutarch relates that the ship used by the Greek hero Theseus (slayer of the Minotaur), was lovingly maintained by the Athenians, who honored the legendary hero by taking the vessel on an annual pilgrimage to make sacrifices to Apollo. Wooden Greek ships, of course, are predisposed to rot, which compelled the men of Athens over the years to replace the various timbers of the ship - removing rotted planks and beams and replacing them with new pieces, to preserve the ship in its original splendor. This, according to Plutarch, sparked a philosophical debate among the Athenian thinkers: if, after enough time had passed, literally every element of the ship - the mast, the sail, the ropes, and every timber of its hull - had been replaced, was it really Theseus’s ship, or was it an entirely different vessel?

This question is mildly interesting, of course, and relates to all manner of philosophical questions about forms and matter and various platonic minutia. For our purposes, however, it forms a useful place to begin an exploration of the remarkable ways that naval combat changed in the 19th century. In this case, the Ship of Theseus is useful because we are similarly talking about literal ships, and like the hero’s vessel, warships in the 19th century went through radical changes. At the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, warships looked essentially like they had two hundred years prior - wooden sailing vessels armed with banks of broadside cannon. By the turn of the century, however, they had been transformed into the essentially recognizable modern battleships that we know today: steel, propeller driven vessels armed with massive naval artillery batteries mounted in rotating turrets.

Both of these forms are very familiar to us - both the wooden ship of the line and the colossal steel battleship are iconic, instantly recognizable weapons systems. There are many places where you can tour one or the other. However familiar we may be with these vessels, at least in their general visible impressions, they are starkly alien from one another. The transition from the sailing broadside warships of Rodney and Nelson to recognizably 20th century battleships was the result of ruthless technological pressures driven in many cases by private inventors, innovators, and industrialists.

Like the ship of Theseus, the transformation of the warship entailed the obsolescence and replacement of literally every component of the ship. Wooden hulls were replaced first with iron and then with steel; muzzle loading cannon firing inert ordinance were replaced with breech loading and fantastically powerful naval artillery with exploding shells; sails were replaced with steam propulsion (powered at first by coal and later by fuel oil). These technological leaps seem logical and straightforward to us, but at the time they were frequently controversial (and often outright rejected at first by conservative naval authorities), incremental, and often connected in a vicious feedback loop. Unlike in previous centuries, this revolution in naval armament was frequently driven by private citizens - entrepreneurs and inventors eager to make their fortunes, who increasingly intruded on the prerogatives of conservative government arsenals and ancient cultures of artisanal weapons manufacture.

Warships, in essence, made a variety of incremental changes that amalgamated old and new technologies - passing through hybrid forms which blended metal and wood, steam and sail - until they became something entirely new. But it was not only the structure of the warship that changed in this way - the economic and bureaucratic systems that built and supported them changed as well. Traditional admiralties and state operated shipyards and arsenals were challenged by the proliferation of private inventors, industrialists, and manufacturers, as society - particularly in Western Europe and the United States - made the leap to modernity and acquired all its signature attributes: mass production, mass politics, and mass mobilization.

The transformation of the warship became a visible symbol of the emerging age of modernity: gleaming with steel, belching smoke into the air, teeming with thousands of personnel, and knitting the imperial world more tightly together than ever with faster transportation and communications - and exponentially more powerful weaponry. With navies across the globe straining to float ever more and ever larger and more powerful vessels, the battleship became the totem weapons system of a world increasingly trapped in its own strategic logic, captive to the insatiable demands of bureaucratized and industrialized war at sea.

The Battleship of Theseus: Modernity at Escape Velocity

In 1807 - two years after the great battle at Trafalgar - Robert Fulton’s little steamship, the Claremont, made the first commercial demonstration of steam powered water transportation by ferrying passengers up the Hudson River from New York City to Albany and back again. The Claremont made the voyage (a round trip distance of about 350 miles) in 62 hours, which was considered a remarkable feat for the time, and developments in steam propulsion would come rapidly. Thirty years later the Atlantic would be crossed in just 18 days by the paddle wheeler Sirius. Although the Sirius also utilized sails (such hybrid propulsion was a standard of early steam vessels), this was the first demonstration of an oceanic crossing with continuous and sustained steam power. By the 1840’s, the clumsy and inefficient paddle wheels of the Sirius and the Claremont had given way to propellers and recognizably modern screw systems, and the power of engines began to increase exponentially. While Fulton’s little Claremont boasted a mere 24 horsepower (about as much as a modern riding lawnmower), the Sirius disposed of 320. By the 1850’s, the British had launched what was at the time the largest ship ever built by far - the 680 foot Great Eastern, which was driven by screw propellers and a massive 1,600 horsepower boiler complex.

In a few decades, then, steam powered ships had had already made the leap from small demonstration projects - essentially the province of hobbyist inventors and entrepreneurs - to fully scaled, if unrefined industrial products. The Great Eastern, for example, was an early but functional ocean liner, capable of carrying passengers from England to Australia under steam power without refueling. Despite these impressive achievements, the advent of steam initially made little impression on the navies of the world, particularly the vaunted British admiralty. The broader transformation of naval warfare would entail not only the radical redesign of the warship, but indeed a total revolution in the relationship between the institutional navy and society’s industrial and economic base.

The naval establishment in Britain had an extremely conservative temperament. This was not merely an ideological disposition, but was also derived from the structural and material apparatus of the navy. The Royal Navy had won global naval supremacy after many decades of war, with its crown jewel at Trafalgar. The British basis for global power rested, at its heart, on a system of naval combat that had not fundamentally changed since the Anglo-Dutch Wars in the mid-1600’s. A vast bureaucratic and manufacturing apparatus existed to support this system - a supply system to provide timber for hulls and hemp for ropes and sails, shipyards and docks for constructing and repairing ships, arsenals for casting iron cannon, and personnel arm finely tuned to produce the particular sailing and fighting skills that were the backbone of British dominance.

Given the scale of the British naval administration, and the fact that its material and human systems were finely calibrated for war in the age of sail, the British admiralty in fact had good reasons to resist the urge to plunge headlong into technological experiments. It (correctly) felt that it had no immediate peers at sea, and given the lack of urgency there was little reason to begin tearing up its powerful naval structures by the floorboards. On the contrary, there was a sense that rocking the boat (pardon the pun) could only serve to narrow the gap between Britain and her would-be rivals. An 1828 memorandum from the Admiralty argued:

“Their Lordships feel it is their bounden duty to discourage to the utmost of their ability the employment of steam vessels, as they consider that the introduction of steam is calculated to strike a fatal blow at the naval supremacy of the Empire.

This may seem like a classic case of “famous last words”, but the plainer truth is that an experienced naval administration, with no real rivals, was always unlikely to embrace speculative changes and abandon a proven and deeply entrenched methodology, in which they were heavily invested. The coming naval revolution would instead be spurred primarily by private actors and and by Britain’s rivals, with the Royal Navy (as the leading force of the day) responding to changes, rather than driving them. As it would turn out, Britain’s vastly superior industrial and financial capacity meant that it did not always need to be the prime mover of technological changes. British economic resources and her vast shipbuilding capacity meant that, even when a potential rival like France made an early breakthrough in ship design, the Royal Navy was never left behind for very long and found it relatively easy to imitate and adopt foreign innovations at scale.

In many ways, the 19th century revolution in naval warfare can be traced through a series of individual names, signifying men who - if not wholly responsible for major technological breakthroughs - are very nearly synonymous with these great leaps. Robert Fulton has gone to the history books as the father of the steam ship. After Fulton comes another singularly significant figure: the French artillery officer Henri Paixhans, father of the exploding naval shell.

Paixhans solved a thorny problem in military engineering. Explosive shells had been used previously, going back to the 18th Century, with Lieutenant Henry Shrapnel’s hollow casing which splintered and ejected shards of metal, but these weapons were used primarily in a siege setting, with mortars firing them at a high trajectory to injure personnel behind fortifications. Before Paixhans, no one had been able to work out how to safely fire explosive ordnance at the high velocities and flat trajectories used in naval combat. His first solution, which became the first functional exploding naval shell, was to rig an explosive shell with a fuse which would be lit by the blast of the gun firing - turning the cannonball into a sort of self-lighting bomb. In 1822, as he was preparing to showcase his newly finished design, he published a book entitled Nouvelle force maritime, which argued that in the near future wooden warships would be rendered obsolete by metal-plated warships armed with explosive shells.

In 1824, a French test confirmed the lethality of the Paixhans gun. The hulk of the decommissioned Pacificator was shot up with Paixhans’s shells, which lodged in the wooden hull before exploding, setting the entire ship alight in short order. The extreme vulnerability of wooden hulls to exploding shells - and in particular the fires that they would spark - was obvious to everyone, and by the late 1830’s both the French and British navies had begun the mass adoption of explosive shells, with other interested parties - like Russia - also placing orders.

On November 30, 1853, a small Russian naval squadron sailed into the harbor at Sinop, on the northern coast of Turkey. Russia and the Ottomans were again at war, and the Russian naval force had been instructed to interdict Turkish naval traffic bringing supplies to the Ottoman ground force in the Caucasus. Armed with a small complement of Paixhans guns with exploding shells, the Russian armada set almost the entirety of an equivalently sized Turkish fleet on fire with just a few volleys. Within two hours of the Russian entry into the Sinop harbor, 11 Ottoman ships had either been destroyed or intentionally grounded by their panicking crews. The Russian fleet then set its guns on the Turkish shore batteries and destroyed them as well.

At the cost of just 37 Russian dead, the little fleet (under admiral Pavel Nakhimov) killed nearly 3,000 Turkish soldiers and sailors and won virtually unimpeded operational control of the Black Sea. The Battle of Sinop - if we can call such a one-sided affair a battle - was the first operational use of the emerging explosive ordinance, and it made a deep impression on both a strategic and a technological level. Strategically, Sinop emphasized that the Ottomans were nearly powerless to oppose Russia and raised the thought that Constantinople was now realistically within Moscow’s reach. The battle became a major inducement to the entry of Britain and France into the conflict which would become the Crimean War. On a more technical level, however, Sinop emphasized the near total lethality of exploding shells brought to bear against wooden warships.

The 1850’s and the Crimean War, then would become a watershed decade for armaments manufacturing and warship design. Before commenting on this war and its ramifications, however, it is worth contemplating the domino chain which revolutionized ship design, and specifically the direction that it flowed.

We can roughly think of the transformation of the warship as consisting of three great changeovers: from inert cannonballs to exploding shells, from wooden hulls to steel with iron plating as an intermediary step, and from sails to steam. Although steam engines were demonstrated early, they were not the first system to be adopted en-masse by the great navies. Rather, it was exploding shells that set off the chain reaction of changes - particularly in that the French, who were far weaker at sea than Britain, were highly motivated to experiment with new technologies.

Exploding shells had made wooden hulls acutely vulnerable, and it was this fact which spurred experiments with metal plating on hulls - particularly in the aim of preventing primitive shells from embedding themselves in the wood and igniting fires. Metal, however, is very heavy, as were the enormous guns required to fire Paixhans’s shells. It is very easy to understand how an escalating race between protection and firepower, with larger guns provoking thicker plating and vice versa in a feedback loop, could very quickly make ships prohibitively heavy and immobile under sail power. It was the sheer weight of these ships which increasingly made steam power a necessity. In effect, then, the modern battleship emerged from a triparte arms race between firepower, protection, and mobility - manifested tangibly as the exploding shell, the steel hull, and the steam engine.

An excellent example of this process in action was the French warship Gloire - a hybrid ironclad warship par excellence. La Gloire had a wooden hull and sails, but also so much more. Outfitted with breech loading artillery and armored with nearly five inches of iron plating (backed by more than a foot of timber), La Gloire proved nearly impervious to any naval artillery then extant. She was also remarkably heavy, with a displacement of some 5,600 tons. This was no obstacle, as a screw propeller powered by steam engine allowed her to attain 13 knots. Most importantly, she was fully ocean-worthy. Her hybrid form - sails and steam, wood and iron alongside each other - spoke to the fact that this was a weapons system in transition, and though she would not remain so for long, at the time she was launched La Gloire was the most powerful naval weapons platform in the world. Protection, firepower, and mobility, all advancing, competing against each other and yet synergizing as the warship evolved.

The Spark: War in Crimea

The Crimean War (1853-1856) would spark the exponential acceleration of change in naval warfare - a fact that at first may seem odd, as it was largely a conflict fought on land. A full recounting of this conflict is beyond our remit here, but we will make do with a brief sketch of its strategic and tactical concepts, before examining in detail the ways that it accelerated technical change in the world’s navies.

The Crimean War was fundamentally a containment war. Russia had emerged from the Napoleonic Wars as the dominant land power in the world, with the largest army in Europe by far and a proven capacity to project its forces from Paris to the Caucasus to Central Asia. Although the aggregate power of the Russian Army concealed many weaknesses (like the need to defend a vast and sprawling border and an eroding economic basis), the general consensus was that Russia was the dominant power of continental Europe, and the events of the early 1850’s raised serious fears that Moscow would dismember the decaying Ottoman Empire, attain Constantinople, and turn the Black Sea into a Russian lake. The Crimean War, in its essence, was a war fought by France and Britain to prevent a strategic Ottoman defeat at the hands of the Russians, and it was fought in Crimea because this was the only place where the French and British could feasibly project armed power against Russia.

Discussions of the Crimean War tend to emphasize the fighting as a primitive preview of the Western Front of World War I. After a series of initial battles at Alma and Balaclava which forced the Russians back on the fortress of Sevastopol, the war transformed into a colossal siege, characterized by extensive field fortifications, trenches, and heavy artillery barrages. Accounts also frequently emphasize the emerging technological gap between Russian forces, who still utilized muskets, and the French and British troops with their newly issued rifled guns.

All of this is fair and of course interesting in its own right, but what matters most to us now is the naval dimension and the industrial base that would support its evolution. Therefore, two topics in particular are very important and ought to be teased out in full: namely, the enormous advantage in supply derived from Anglo-French naval lift, and the fact that the Crimean War served as a spark that ignited a revolution in arms manufacturing. Rather than focusing on the technical gap that existed between Russian and allied forces during the war, it is important to understand that the war set off an explosion of technological change in the field of armaments. These changes came too late to impact the war in Crimea, but would dramatically change the form of future wars.

Although naval combat was of secondary importance in Crimea, seaborne logistics were not. Anglo-French forces had a decisive and overpowering logistical advantage despite the fact that the war was fought on Russian soil. With fighting centered around Sevastopol, on the southern periphery of the empire, Russian forces had extreme difficulties ensuring an adequate delivery of munitions and other supplies, while the allies - supplied by sea - had access to an enormous logistical lift. French steamships were able to make the trip from Marseilles to the Black Sea in twelve to sixteen days (depending on the weather), while Russian reinforcements and supplies - traveling overland with thousands of animal drawn carts - could take months to reach the front from the Russian interior. Although allied supply was hardly unlimited, French and British forces were much more tightly connected to home, both logistically and in communications, than the Russians, who nominally *were* fighting at home.

In addition to the growing use of steam ships for logistical functions, the Crimean War was also the first major war to make use of the telegraph for communications. When combined with the presence of journalists embedded with the troops (again a first), this connected civilians in France and Britain with the fighting in an entirely new and intimate way, and provoked intense public interest in the war. This fact would have profound implications for weapons manufacturing, as we will see shortly. In contrast, the Russians - who had built up neither telegraph nor railroad connectivity to Crimea - were largely out of the loop. Tsar Nicholas I was said to regularly complain that he got better and more timely information from French newspapers than he did from his own commanders.

In short, the Crimean War prefigured the emerging totalization of war which would be made possible by the twin technologies of steam power (whether in locomotives or ships) and the telegraph. Steam ships and railroads would soon be able to move men and material in previously unthinkable qualities, while the telegraph would make possible the prospect of command and control of ever larger armies. These were the essential tools of mass mobilization and mass politics that would soon allow the states of Europe to fling armies of millions at each other.

In enumerating the consequences of the Crimean War, however, we at last come to (in my view) the single most important outcome: a total revolution in armaments manufacturing. The Crimean War, without exaggeration, led directly to the formation of what we might recognizably call the “military industrial complex”, though here I use the phrase without the negative connotation usually implied. The Crimean War sparked a revolution in arms production for two reasons: first, it exposed the utter obsolescence of existing models, and secondly it inculcated an immense interest among private citizens and inventors to offer something better. To demonstrate these changes, we will focus primarily on the British case.

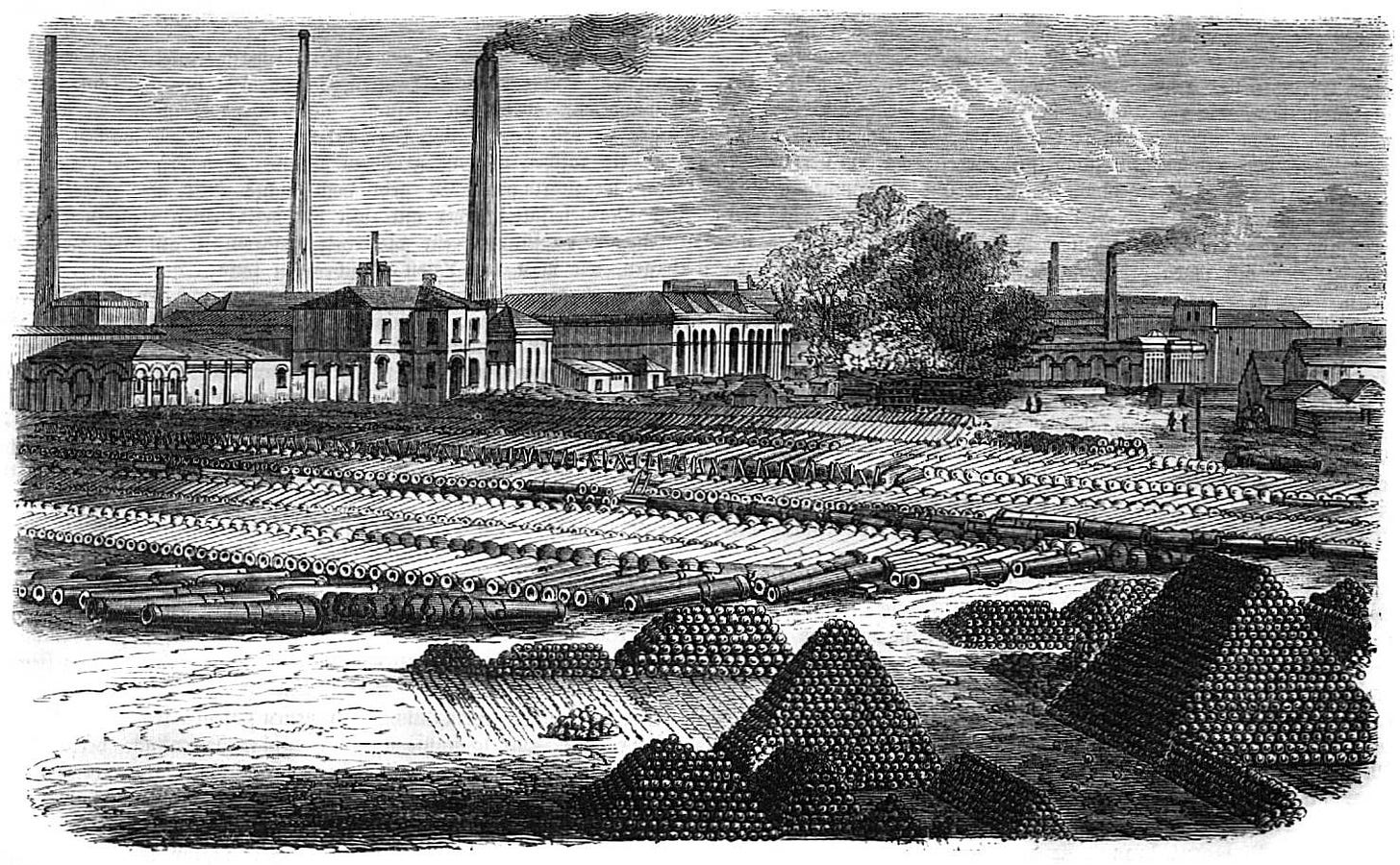

Weapons manufacturing in Britain had long been the domain of a decentralized web of artisan craftsmen, located primarily in London and Birmingham. Making guns, in other words, was a craft, with artisans essentially working as subcontractors for the state-owned Woolwich Arsenal. Craftsmen specialized in making specific components of the finished weapon and delivered batches of these parts to trickle up the chain towards final assembly. This artisanal, dissipated system of manufacture dovetailed with the conservativism of the military establishment to freeze weapons technology. The British officer corps taught the same basic drill (that is, the process for synchronized marching, reloading, and firing), and British artisan gunsmiths made the same basic musket, and nothing changed. The mainstay British musket - “Brown Bess” as she was affectionately called - remained virtually unchanged from the time of Marlborough (the early 1700’s) all the way through the Napoleonic wars and into the middle of the 19th Century.

In the Crimean War, however, this artisanal system of gunsmithing showed its obsolescence, in that it proved unable to either expand its output or adapt to emerging new designs in firearms. When war broke out in Crimea, the British Army attempted to place large new orders for small arms - but to the artisans of London and Birmingham, this appeared to be the perfect opportunity to go on strike for higher wages. As a result, the Crimean War exposed the artisanal manufacturing system to be inelastic and unresponsive to the army’s needs. Precisely when the army was demanding a surge in production, work stoppages and strikes led to a stark drop in output. Simultaneously, these same workmen - accustomed to practicing a very old and unchanged manufacturing process to make Brown Bess muskets - proved resistant and inflexible when the government tried to make the transition to new rifled models.

Clearly, something had to change. Fortunately, there was already an alternative model of firearms manufacture being practiced in America. The American arsenal in Springfield, Massachusetts - and a bevy of private American gunmakers - had already proven the viability of mass production using milling machines to cut interchangeable components. The British had seen a demonstration of this up close: in 1851, at the Great Exhibition in London’s Hyde Park, Samuel Colt showed off his revolvers and demonstrated their interchangeability by dismantling a whole slew of pistols, mixing up the parts in a great pile, and then reassembling them into working guns.

The difficulties with the artisans, combined with the proven viability of American mass production, compelled the British to finance a new manufacturing plant at Enfield based on the “American system of manufacture”, as it was called. Expensive milling machines were ordered from the Americans, and although they arrived too late to impact the war in Crimea, by 1859 the Enfield plant was operative. Meanwhile, newly designed machines at the government Woolwich Arsenal were capable of manufacturing hundreds of thousands of bullets per day. The new breakthroughs in manufacturing were hardly limited to government enterprises, however - two major private manufacturers emerged in Britain in the 1860’s, located in the old artisanal manufacturing hubs in London and Birmingham.

The advantage of the emerging system of mass production was not only in the scale of the output, but also in the speed with which armies could produce and deploy new weapons. Before the Crimean War, the glacial speed of production discouraged innovation in design, because rolling out the new weapon required cajoling thousands of artisans in a decentralized production system to adjust their processes. Now, a new weapon could be produced en-masse simply by designing new jigs and forms for the automatic machine tools. Brown Bess changed very little over hundreds of years, but now a new rifle could be deployed en-masse in short order. Both France and Prussia, similarly, were able to totally reequip their armies with new rifles in about four years using American-style machining lines.

At the same time, the Crimean War had exposed conservative military officers to the fearful prospect that future wars would be fought with new weapons with which they had little or no direct experience. The power of the new breech loading rifles and exploding artillery shells jolted much of the European military caste out of its slumber, and in general made them much more open to innovation and change.

The Crimean War sparked a similar revolution in artillery manufacture and metallurgy, which was to have profound implications for our particular subject of naval warfare. The link to Crimea was first the powerful demonstration of exploding shells and armored warships (the French in particular made effective use of iron-plated floating artillery batteries to shell Russian fortifications), and secondly the intense interest of the public in a war which for the first time was being comprehensively covered in real time by embedded journalists connected to the home front via telegraph.

At least two of Britain’s great industrialists at this time - Henry Bessemer and William Armstrong - were provoked directly by their interest in the Crimean War. Bessemer spent the early part of the 1850’s experimenting with methods to cheaply produce steel at scale specifically for manufacturing artillery barrels, and finally broke through when he discovered a novel method of refining by blowing air through molten iron ore. Thus, the mass production of steel, which is both stronger and more easily worked than iron, was gifted to the world. This remains one of the most important technological breakthroughs of the modern world.

The “Bessemer Process” broke the world through to an entirely new age of metallurgy, which quickly made old methods of casting artillery utterly obsolete. This is not, of course, to imply that steel would never have come to predominate without the Crimean War, but it is worth emphasizing that Bessemer was specifically grappling with an application in armaments. In his autobiography, he wrote that the artillery problem: “was the spark which kindled one of the greatest revolutions that the present century had to record… I made up my mind to try what I could to improve the quality of iron in the manufacture of guns.”

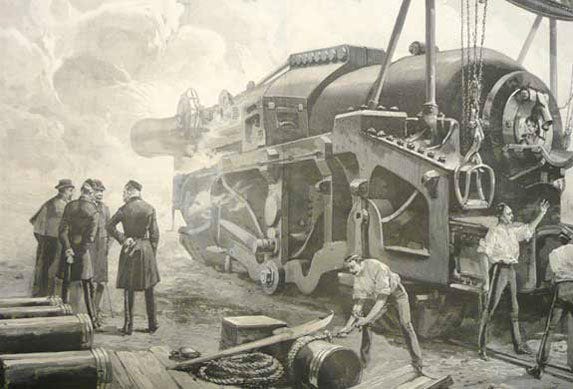

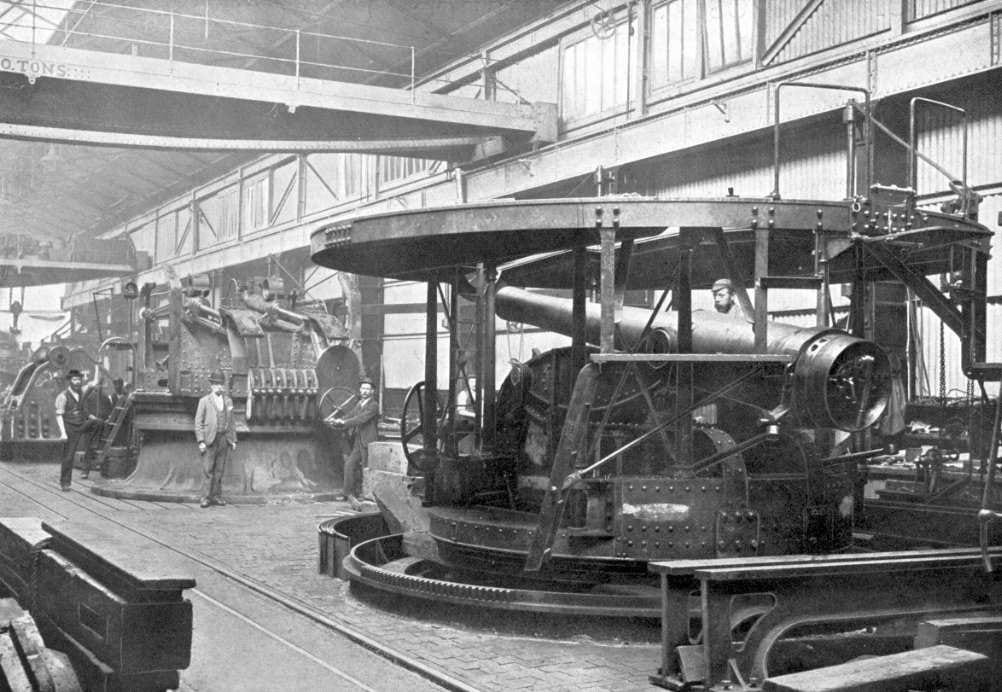

Meanwhile, the industrialist William Armstrong remembered reading an account of British artillery in action at the Battle of Inkerman, in Crimea, and promptly sketched out a design for a breech loading artillery piece. His remark, similarly to Bessemer’s, was that it was “time military engineering was brought up to the level of current engineering practice.” Armstrong would soon become Britain’s most prolific private artillery designer, and although the Navy eschewed his guns and chose to continue procuring artillery from the state Woolwich Arsenal, Armstrong’s guns created a commercial pressure that drove engineers at the arsenal to develop new designs of their own.

Although government operated artillery arsenals fought to maintain their monopoly on the manufacture of heavy guns, it was impossible to ignore the developments being driven by private inventors and industrialists. Henry Bessemer had blown the game wide open by gifting the world cheap steel at scale, which made it possible to produce not only munitions and artillery barrels but eventually the hulls of ships to exacting standards without the brittleness characteristic of iron. Meanwhile, private manufacturers like Armstrong, his rival Joseph Whitworth, and the Prussian industrialist Alfred Krupp, pushed the envelope with new designs and were eager to point out the superiority of their guns.

Everything was now in place for warships to undergo their next phase of evolution - transitioning from the hybrid midcentury forms, which combined wood and iron, sail and steam - to recognizably modern battleships. The chain of innovations is, in fact, relatively straightforward to trace.

A race had already begun between protection and firepower, particularly between the French and British who, although allies in Crimea, continued to eye each other’s ship designs warily. When the French launched La Gloire in the late 1850’s and boasted that its iron plating was invulnerable to any extant naval gun, it naturally pushed the British to simply design a bigger and more powerful artillery piece. As armor got thicker and thicker (eventually giving way to hulls made entirely of thick steel), guns got bigger and bigger.

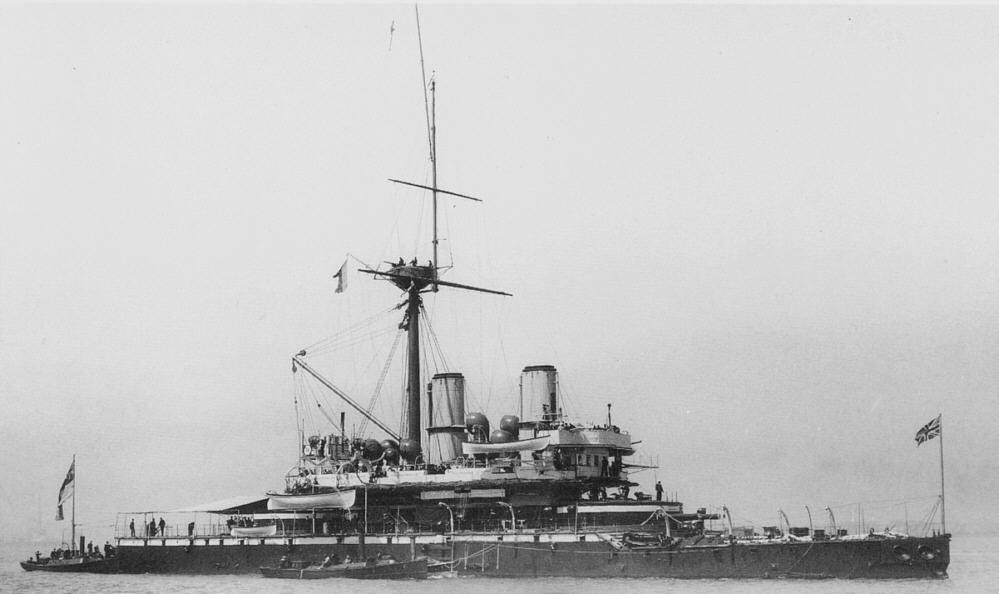

The increasing size of the guns forced a total reevaluation of the layout of the warship. Designing ships with rows of cannons laid out along the sides was now abortive, as the guns were so heavy and ponderous that placement on the outer hull threatened the stability of the ship. Guns therefore had to be placed midships along the deck of the vessel for purposes of stability, and that in turn meant that masts and sails had to be removed to give the guns a free field of fire. Thus, by 1871 the Royal Navy had launched the HMS Devastation - the first capital ship to be both powered entirely by steam (she carried no sails at all) and to have her guns mounted on the top deck, rather than below in the hull. When the Devastation shed her sails and the gunports in her hulls, the last vestiges of Nelson’s broadside sailing ships were finally gone.

Further developments were soon made. Mounting the guns on the top deck of the ship exposed the gun crews to enemy fire. The solution, obviously, was to encase the gun in an armored turrets, and these turrets needed to be able to turn in order to bring the gun to target. Therefore, the turret needed hydraulic power, and this by extension meant more steam, which required bigger and more boilers. Thus, we get the battleship.

In summary, technologies were emerging in the early 19th Century that would radically change naval warfare, transforming the venerable ship of the line into recognizably modern battleships, but Admiralties - particularly in Britain - were initially slow to adopt these changes given their long established systems of shipbuilding, training, and maintenance. The primary inducement to break this system open was the exploding shell - French tests indicated that wooden warships were highly vulnerable to these emerging weapons, and the Crimean War proved this beyond a shadow of a doubt, first in the Russian defeat of the Ottoman fleet at Sinop, and again with the Anglo-French use of exploding shells to reduce Russian fortifications in Crimea.

The advent of the exploding shell began an incremental race between armor and firepower which would take off fully after the Crimean War, as the conflict spurred private innovations in metallurgy and artillery design by men like Bessemer and Armstrong. Simultaneously, the war exposed the inflexibility and inadequacy of the old artisanal system of manufacturing and spurred state arsenals to pursue mass production along the American model, while making military establishments more open to innovation and input from private industrial enterprises.

The result was a fantastic acceleration of what we might refer to as weapon cycling times, or generation times: in other words, the rate at which weapons became obsolete and were replaced by newer models. Cycling times used to be measured in centuries: iconic weapons systems like the Brown Bess musket or the broadside sailing ship changed very little over very long periods of time. From the Anglo-Dutch Wars to Nelson, the broadside line ship remained generally the same and changed mostly by becoming larger. In the mid-19th Century, however, ships became obsolete faster and faster. In 1861, the Royal Navy launched the HMS Warrior - an iron hulled warship with mixed steam and sail propulsion. The most powerful ship in the world when she launched, the Warrior was made utterly obsolete just a decade later with the 1871 launch of the Devastation. The idea of a ten year old ship being essentially useless in combat would have been insanity to a 17th or 18th Century admiralty, but now it was unremarkable.

In regards to warships design more specifically, the interplay between protection, firepower, and mobility created a feedback loop that drove ships towards configurations that seem very nearly predestined by the nature of the underlying technology. Exploding shells necessitated armor plating which became thicker and thicker, driving the design of ever larger guns to defeat the thickening armor. The size of these guns eventually ensured that they would be moved from gun decks inside the hull to armored turrets on the deck, which made it impossible to maintain masts and sails. This implied steam both for propulsion and to power the hydraulic turrets, and the powerplants of ships grew correspondingly larger to accommodate the growing bulk of the heavily armored vessels. From Robert Fulton’s 24 horsepower engine in 1807, boiler complexes grew by leaps and bounds - the powerplant on the Devastation, for example, provided more than 6,600 horsepower.

In short, what I have endeavored to demonstrate here is that the design of warships followed an extremely logical course, and the transition from broadside sailing ships to early modern battleships - although astonishing in its totality - in fact consisted of a series of fairly predictable incremental changes, beginning with the introduction of exploding shells. To return to the Ship of Theseus, we can say that at midcentury warships still generally resembled the old line ships from the golden age of sail, albeit with larger guns, iron plating attached to the hull, and the odd smokestack poking out here and there. Shortly after the Crimean War, however, these ships became something entirely new, recognizable to us as early modern battleships: shedding the last vestiges of their masts, adding more boilers, housing their guns in turrets, and eventually boasting hulls made entirely of steel.

One could almost go so far as to say that the battleship was practically inevitable from the moment Henri Paixhans demonstrated his fuse shell. The Crimean War, which demonstrated in unequivocal terms the enormous combat power of shell artillery, sparked a revolution in weapons manufacturing, with mass production, steel (compliments of Mr. Bessemer), and private manufacturers driving the warship into a new era - the era of steel and steam and mass armies and terrible destruction. Or, as Victory Hugo (of all people) put it:

"Earth! The shell is God. Paixhans is his Prophet."

Earth and Water: Conjuring the Great Snake

While the British and the French led Europe into a total revolution in naval warfare, the old continent was mercifully spared a general continental war of the sort that had ravaged it in the Napoleonic era. Accordingly, after Trafalgar in 1805, there would be no general fleet actions by the great powers for the remainder of the Century. In fact, the broader irony is that despite the enormous advances made in ship design and armaments and the swelling industrialization of war, the 19th Century was remarkably light on naval combat of any kind - for Europe at least. The Battle of Sinop was a notable exception, but tactically it was hardly very instructive or elaborate: a Russian fleet more or less set fire to an Ottoman armada. If anything, Sinop was more like arson than a proper fleet battle.

Thus, although it was obvious that warships were changing in a very fundamental way and would provide astonishing combat power in future wars, European navies did not experience this firsthand and did not fully understand what naval battle would be like. However, there were hints and demonstrations to be seen, if one could cast a wider eye and look beyond the great powers of Europe. There were other navies, new emerging states, and looming powers.

Between the fall of Napoleon and the beginning of World War I (essentially a round 100 years), three particular geopolitical developments eclipsed all others in their importance. Two of these were the Meiji Restoration in Japan, which produced an assertive, consolidating, and rapidly modernizing power in East Asia, and the unification of Germany under Prussian headship, which created an extraordinarily powerful state in Central Europe, with consequences that are well known to us. The emergence of powerful Japanese and German states was of immense interest and importance to the traditional great powers of Europe, and in particular Russia, which now faced rapidly industrializing powers on both its western and eastern flanks.

The third great happening of the long 19th Century, however, was by far the most important. This was the American Civil War. The Civil War today is shrouded in trite political debates and heavy handed displays of historical erasure. Most people, if asked, would undoubtedly say that the most important outcome of the Civil War was the abolition of southern slavery, with perhaps some vague addendum about preserving the Union without a clear notion of what it meant. Between Confederate lost cause romanticism and the turbocharged civil rights regime, there is little common ground and a lack of interest in something as vague and tired as geopolitics.

The US Civil War was, as I would argue, the single most consequential act of empire building in modern history. The simple fact was that the Confederate South was a nation, or at least was in the process of becoming one, with a wealthy agrarian economy, peculiar social forms, and a patrician leadership caste that was largely alien to the industrial, urban north. Southerners affirmed their membership in this emergent nation with exceptionally high levels of military participation, the willingness to endure extreme privation, and a new schema of southern symbols and hagiography. This emerging southern nation was strangled in its cradle by the powerful north and then re-integrated into the Union in a complex political settlement - the cost of which was abandoning southern blacks to a postwar racial caste system.

The essential function of the Civil War was to preserve a growing American empire with continent-spanning dimensions and consolidate control of the vast American space under the increasingly penetrating power of Washington. The future would belong to powers with the ability to wield resources on a continental scale: super states able to exploit far flung resources and lands through the emerging power of the railroad and the increasingly sophisticated bureaucratic apparatus of state. On many killing fields across the Confederate heartland, the Union affirmed its control of a continent and preserved the embryo of America’s coming global supremacy.

Fought as it was in the interior heartland of America, the Civil War was generally characterized by set piece battles on land, and cursory accounts tend to emphasize, as the main cause of Union victory, the north’s overwhelming superiority in population, industrial capacity, and logistics - particular given superior northern railroad density. This is all fair enough, and the war was ultimately a clash between a populous, industrial north and a relatively thinly settled agrarian south. The Union had 70% of the prewar population, 70% of the rail network, and 90% of the manufacturing output, leaving razor thin odds for the South. A simple open and shut case, if there ever was one.

The Union struggled mightily in the early years of war, however, with the question of just how to bring this preponderance of force to bear against the Confederacy, and displayed no small measure of strategic indecision and even paralysis. Nowhere was this more evident than in the naval dimension of the war.

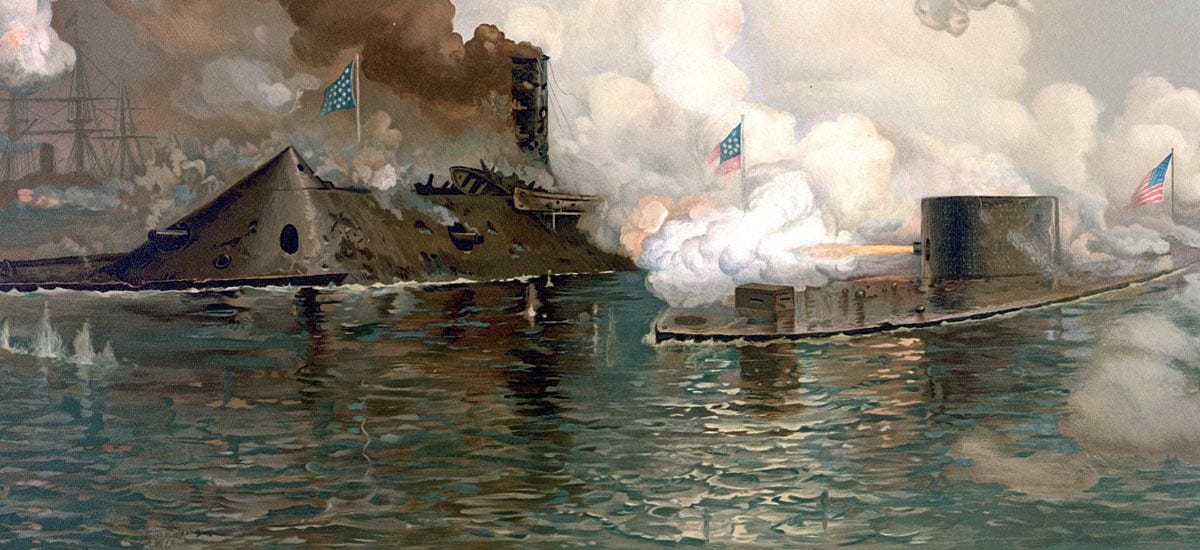

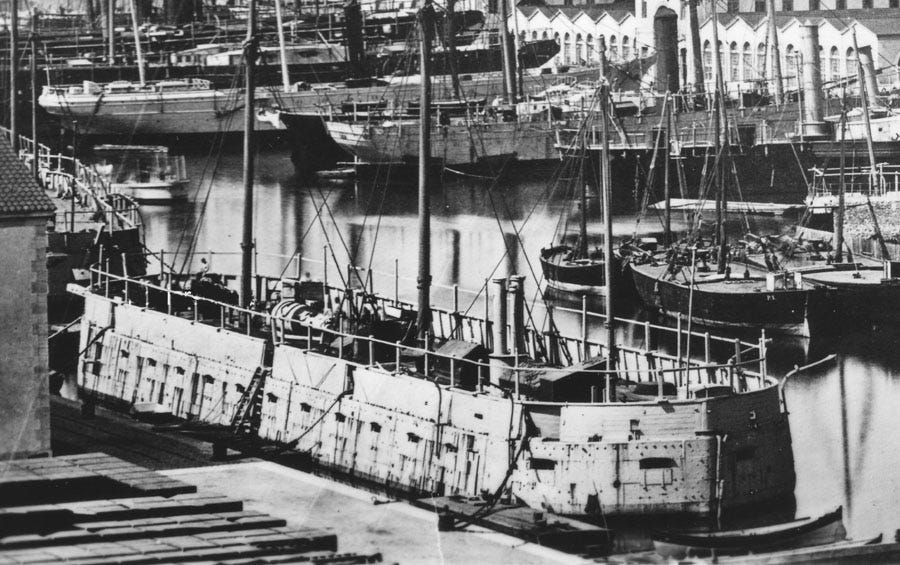

The naval theater offered immense opportunity for the Union. When secession began and signaled the outbreak of war in 1861, only two significant naval installations fell into Confederate hands - namely, naval bases at Norfolk Virginia and Pensacola Florida. The base at Norfolk (the Gosport Shipyard) was of particular importance, with the Confederates taking custody of the dry dock, considerable warehouses full of munitions, and the wreck of the Merrimack. The latter was a brand new steam powered screw frigate of the US Navy, which had been scuttled by evacuating Union forces, though not well enough: southern engineers were able to raise the wreck in salvageable condition and return it to combat.

Notwithstanding Norfolk and a determined effort by the Confederacy to build out its naval capabilities, the shipbuilding capacity of the North was vastly greater, almost to a laughable extent. The South began the war with roughly 14 seaworthy ships, and a herculean effort would manage to raise the force to 101 vessels throughout the war. In contrast, the North had some 42 combat ready vessels at the outbreak of war, and would raise this number to more than 670 ships by the time of Confederate surrender - in effect, the force ratios on the sea increased from a 3:1 northern ship advantage at the start of war to nearly 7:1 by the end.

The United States had a considerable amount of firsthand experience which demonstrated how potent sea power could be when leveraged properly to support overland forces, in what would we would now call joint operations. The British had made great use of sea power in both the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, in particular with the Royal Navy wrecking the American defense of New York in 1776, and British control of the Chesapeake leading to the climactic burning of Washington in 1812. Furthermore, the Union’s senior officer, Commanding General of the Army Winfield Scott, had gained intimate experience with joint operations in the Mexican-American War, when he conducted an amphibious invasion of Mexico. Scott became a particularly powerful advocate of joint operations and a naval grand strategy, and it was unfortunate that the venerable old General did not remain in command after the first year of the war.

The operational possibilities were myriad. In addition to a broader strategic campaign to blockade Confederate ports and isolate the under-industrialized southern economy, seaborne forces could ensure secure lines of communication for Union armies fighting in the Confederate littoral. They could be used to enhance Union operational mobility and turn enemy defenses by landing in the rear.

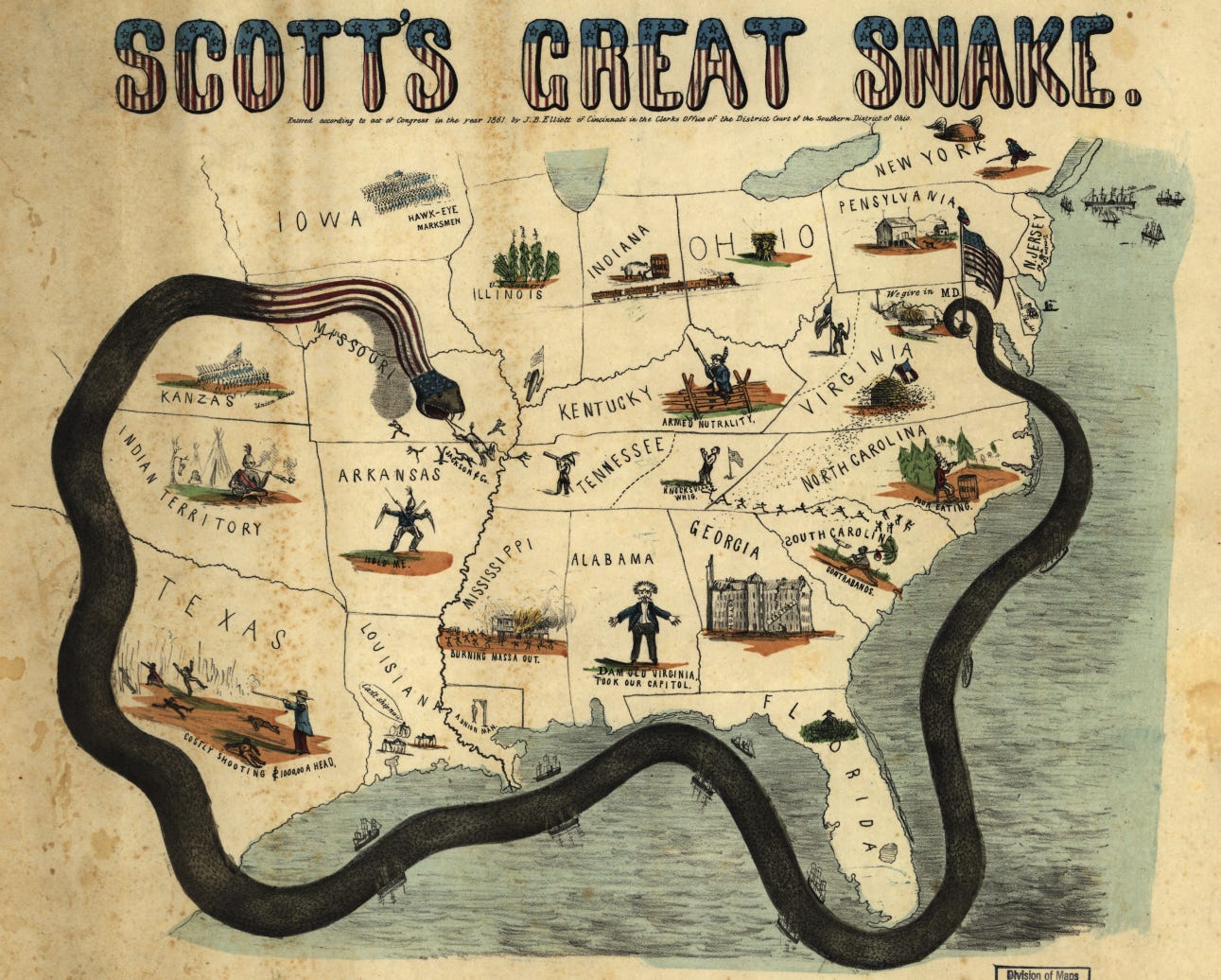

General Scott advocated a broad campaign predicated on joint operations which put naval combat power in a position of priority. In a formulation that Union newspapers would label the “Anaconda Plan”, Scott proposed a two-fold approach that would simultaneously blockade Confederate ports while launching a riverine campaign down the Mississippi, which served as the great arterial waterway and provided penetration deep into the Confederate heartland. As Scott put it, a campaign in the interior along the Mississippi would:

Clear out and keep open this great line of communications in connection with the strict blockade of the seaboard, so as to envelop the insurgent States and bring them to terms with less bloodshed than by any other plan.

Although Scott would leave his post late in 1861, to be replaced by the much-maligned George McClellan, his tenure in the opening months of the war was sufficient to set in motion strategic developments along these lines. Although the war did not proceed precisely as Scott envisioned it, two critical elements of his thinking - a riverine campaign along the Mississippi and a blockade of Confederate ports - would become pillars of the coming Union victory. Indeed, while the campaigns of Robert E Lee and the ferocious battles in the Virginia theater are generally among the most famous moments of the war, it is inarguable that the coming Union blockade and the conquest of the Mississippi were the most critical strategic developments of the conflict, and both were intimately dependent on naval combat power.

Although the Union boasted both a larger fleet at the outset of the war and a significantly greater shipbuilding capacity, blockading the Confederacy was much more difficult than it sounded. While Europeans continued to look on American military proficiency with a strong tint of smugness, the reality was that the Civil War was a military-logistical challenge far greater than any European army or state had ever attempted. This was because the United States was, in a word, huge. The eleven states which comprised the Confederate States of America cover some 780,000 square miles of greatly varied terrain - greater in size than Britain, France, Germany, Italy, and Spain combined. The length of the Mississippi theater alone (running from the Union base of support around Cairo, Illinois all the way to the sea) is nearly equal to the north-south dimensions of France.

In short, the Confederacy was a vast state with 3,500 miles of coastline and many hundreds of miles of navigable rivers. Blockading such an enemy was an imposing task - by far the largest such blockading operation ever undertaken, and even more daunting given the miniscule naval force (42 combat-worthy ships) available at the outset of war. In addition to building up the forces needed to undertake the blockade, the intended campaign along the Mississippi would require building out a riverine force of both gunboats for combat operations and transports for troops and material.

Fortunately for the Union, the vast geography of the Confederacy also had implications that worked in their favor. The size of the Confederacy, and the growing paramount importance of rail transportation, meant that the Union did not have to blockade the entire coastline - only those ports with the infrastructure and rail connectivity to serve as viable transit hubs for the enemy. By far the most important Confederate port was New Orleans, at the mouth of the Mississippi. To New Orleans could be added Galveston (Texas), Mobile (Alabama), Savannah (Georgia), Charleston (South Carolina), and Wilmington (North Carolina). If the Union Navy could blockade these ports, which sat at vital southern railheads, it would be enough to largely choke off the southern states, and imports at smaller ancillary ports would never be able to meaningfully offset the loss of these major hubs. Meanwhile, Virginia’s sea access was cut off with relative ease thanks to built-in Union dominance of the Chesapeake.

Late in the summer of 1861, the Army-Navy Blockade Board convened to sketch out how all of this could be accomplished. They clearly understood that a blockade could be achieved by isolating the Confederacy’s major ports, but even this task required identifying a series of coastal installations which would have to be captured. Above all, the navy would require coaling stations - a new wrinkle in war planning. By this time, the US Navy - like its European counterparts - had transitioned to steam power, but the steamships of the day were woefully inefficient coal-guzzling monstrosities which required regular restocking. Maintaining a blockade around major Confederate ports would require not only an adequate force of warships, but also nearby coaling bases under Union control.

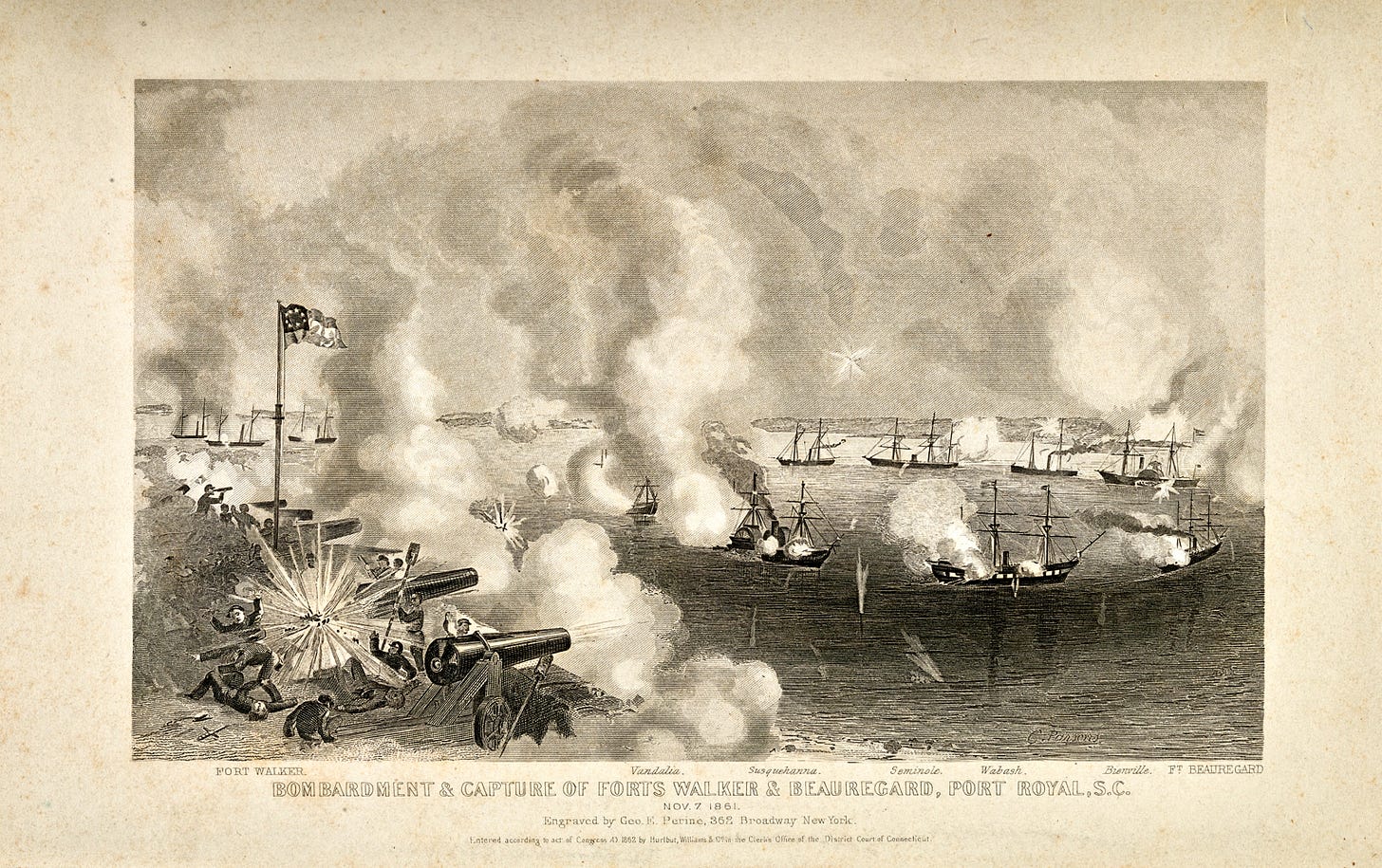

The blockade board eventually identified a series of locations that were to be captured and used as coaling stations and bases of support for blockading fleets - these included Fernandina, Florida, Bull’s Bay and Port Royal, South Carolina, and Ship Island, Mississippi. The latter was to prove particularly important - located between Mobile and New Orleans, Ship Island would serve as a base for blockading forces in the Gulf and allowed Union Ships to patrol both the mouth of the Mississippi and the entrance to Mobile Bay.

The naval theater offered the Union a chance to win a decisive victory relatively early in the war, but this opportunity was wasted due to a variety of institutional neuroses. These began with the retirement of Scott and his replacement by McLellan, who had less appreciation for joint operations and viewed the pivotal axis of the war to be the land front along the Virginia border, with naval operations playing a subordinate, supportive role. Furthermore, there was no systematic or institutional mechanism for coordinating Army and Navy operations (particularly when the blockade board disbanded after issuing its recommendations in 1861), and Lincoln - still shaky as commander in chief - generally failed to adjudicate disputes between the services, of which there were many.

The Union’s 1861 capture of Port Royal, South Carolina offers an instructive example. The Union foothold at Port Royal had essentially driven a wedge in the lower Confederate seaboard, giving Union forces a powerful position between Savannah and Charleston. The threat was severe enough that Confederate high command dispatched Robert E Lee to sort out defenses along the southern coast. Many Union officers saw Port Royal not merely as a naval base to support the blockade, but as a place where they could land and supply an army deep in the enemy’s rear. Such a vision, however, would require close coordination and strategic synchronization between army and navy - but the army’s commander, McLellan, was preoccupied with his campaign into Virginia, and the Navy was much more concerned with the blockade and hardly wanted to subordinate itself to a support arm of the army. Admiral Gustavus Fox, who commanded the naval detachment at Port Royal, encapsulated the views of many naval officers when he said “my duties are twofold; first, to beat our southern friends; second, to beat the Army.”

In the end, then, the Union simply lacked the institutional mechanisms to systematically coordinate joint operations and establish what we would call unity of command. Tactically, Union forces proved capable of assaulting and capturing sometimes formidable Confederate coastal forts, but a lack of strategic perspective prevented the North from fully capitalizing on these footholds. Rather than landing forces for operations in the Confederate rear, the Union’s chain of coastal positions were largely used as bases of support for blockading ships.

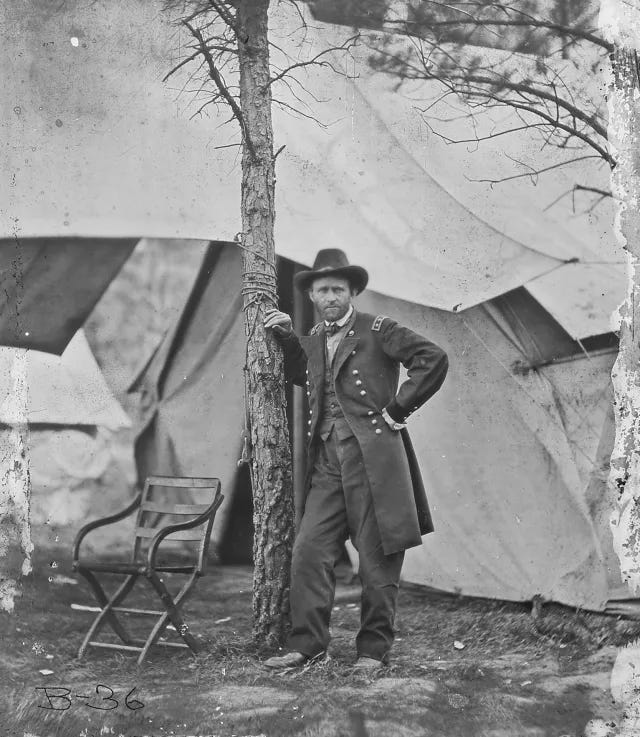

There was, however, one theater where commanders managed to develop a working practice of joint operations. Fortuitously for the Union, this was the single most strategic theater of the war, and it was here that Ulysses Grant found himself in the driver’s seat.

Grant and the Turtles

Today, Cairo, Illinois is a dilapidated and depopulated little ghost town, full of boarded up buildings and poverty and social rot. In the early 1860’s, however, it occupied the single most strategic position of the American Civil War. Cairo lies at the place where the four great rivers of the American Midwest - the Missouri, the Ohio, the Tennessee, and the Cumberland - converge and meet both each other and the almighty Mississippi. It is thus the place where vast flows of riverine traffic converge, and the place where Union forces had the opportunity to use those rivers to penetrate deep into the Confederate space.

The potential for penetration via the Mississippi and its tributaries was astonishing. The state of Tennessee can be almost entirely subjugated through the access provided by the Cumberland and Tennessee rivers - these waterways offer direct access to Nashville and Chattanooga, and would provide Union forces both efficient logistical connectivity via boat and the ability to easily move men and artillery. The importance of the Mississippi, of course, needs no real elaboration - it was the artery of the South, both dividing the Confederacy in two and providing unimpeded access to Louisiana and Mississippi. A Union army operating from Cairo, lying directly on the confluence of the region’s five great rivers, was like a blood clot threatening to descend into the Aorta of the Confederacy. And since this Civil War was the conflict which guaranteed America’s immanent status as the world’s most powerful nation, we can say with only a little exaggeration that, for a moment at least, Cairo was the pivot of world affairs.

While 1861 and 1862 saw few decisive developments in the eastern theater of the war (the theater of Lee, which draws most of the attention in historiography), Ulysses Grant would blow the western theater wide open with series of riverine campaigns which made ruthlessly effective use of combined operations. Grant’s life prior to the Civil War was one of hardship and instability, but when he was given command of Union forces in the Cairo district, luck was finally and firmly on his side: his operational possibilities were second to none, and he had powerful new technological means to exploit them.

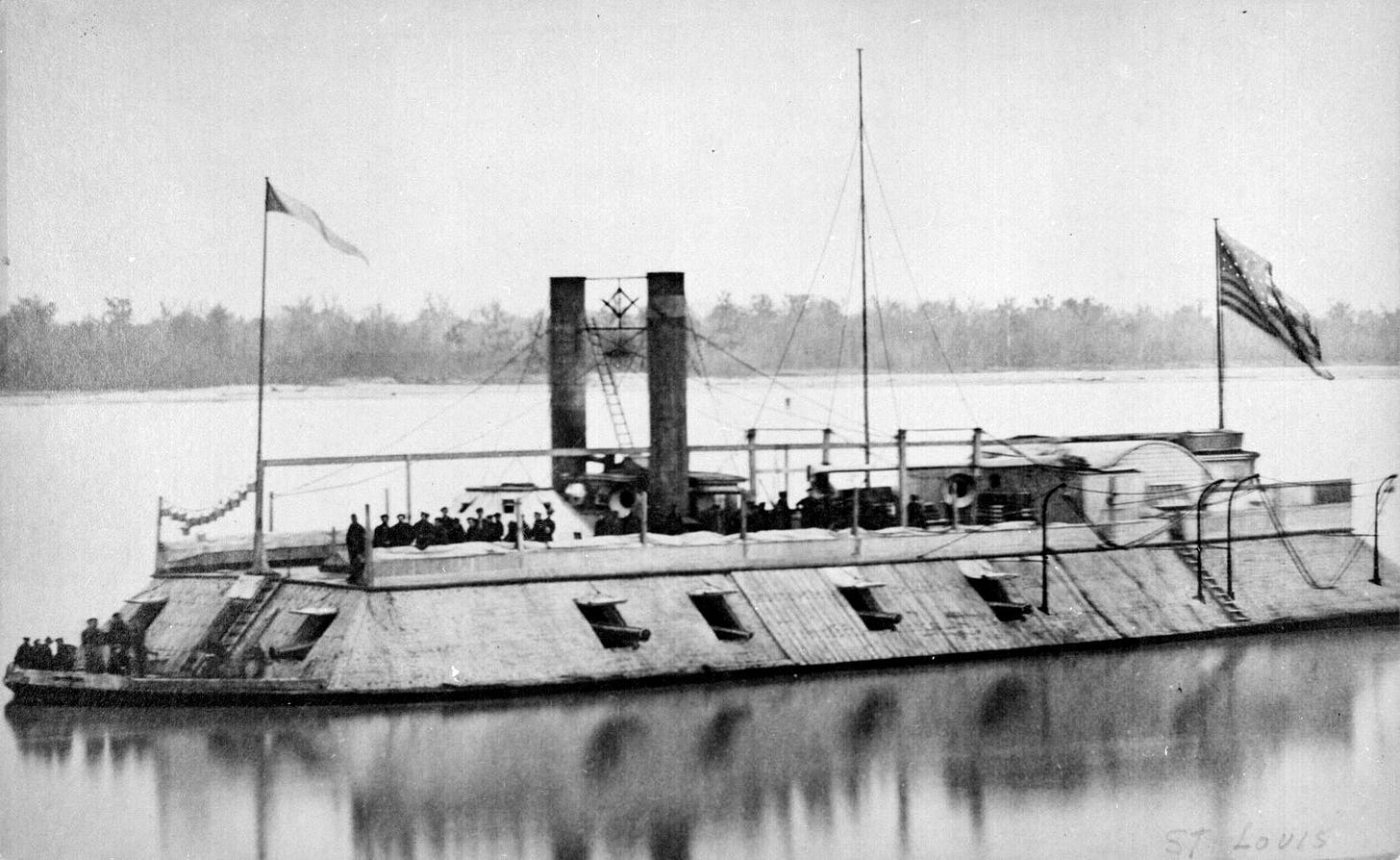

Grant’s riverine campaigns in the western theater would make use of one of the Civil War’s novel weapons systems: the Eads Gunboat, formally the City Class Gunboat and otherwise affectionately known simply as the turtle. Designed by wealthy and renowned inventor and industrialist James Buchanan Eads of St. Louis, the steam powered turtles were remarkable and quirky little vessels that packed a tremendous punch and represented the cutting edge of naval combat systems in the day. Some 175 feet long and 50 feet at the beam, the steam powered turtles boasted thick armored plating arrayed at a sharp angle to deflect shot, and were armed with a whopping 13 cannon of various calibers. Most importantly, they had a draught of only six feet despite their tremendous weight - providing, in essence, a highly mobile and well armored ship capable of traversing the rivers with ease. Their combination of mobility, protection, and firepower made them an essentially novel weapons system and a harbinger of the industrial era of war. While the Eads boats were perhaps the most powerful and innovative vessels at Grant’s disposal, they were not alone - Union forces also constructed a flotilla of flat-bottomed boats which carried siege mortars for reducing Confederate fortifications, and a host of barges for transport.

The Eads Gunboats were not only the perfect weapons system for a campaign which would be centered on the great rivers, but also a potent demonstration of Union superiority in manufacturing and engineering. Eads and his men were able to deliver a fleet of eight working gunboats just four months after receiving the contract, with more vessels in the works. In contrast, the Confederacy - which lacked an equivalent base of engineering and innovating industrialists - had nothing even remotely comparable to contest the rivers. Although the south would scramble mightily throughout the war to deploy ironclad warships, they were always too late and too few to match Union assets. Furthermore, although the North was not nearly as urban as the South liked to believe (Confederates frequently derided northerners as soft city boys who had never held a rifle), the more industrialized quality of northern society now proved to be an asset. Grant’s forces contained no shortage of railroad workers and mechanics who were more than capable of operating and repairing the steam engines on the gunboats - thus, although custody of the ships nominally belonged to the Navy, much of the crew and in particular the mechanics were soldiers from Grant’s army formations. In the modern parlance, we would say that Northern industrialization gave Grant organic engineering capabilities.

The ensuing campaign would provide an iconic demonstration of riverine operations, and more generally revealed the immense value of rivers are arteries for movement, supply, and the delivery of combat power.

The Confederates made the opening move late in 1861 and got the jump on Grant, with General Leonidas Polk seizing the city of Columbus, Kentucky, allowing him to block the Mississippi just a few miles downstream of Grant’s base in Cairo. The move made some sense, as far as Confederate operational presumptions went: commanders on both sides continued to view the Mississippi as the vital waterway of the war, and not without some justification. What Polk failed to grasp, however, was that the uniquely dense waterways of the region would give Grant ample opportunities to bypass Columbus. The real operational prize in the region was not the course of the Mississippi itself, but the area farther upstream where all the great rivers - the Ohio, the Cumberland, and the Tennessee - converged on the Mississippi. Polk could block the Mississippi, but Grant’s position around Cairo allowed him to access any of the region’s rivers at his pleasure.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the single most important position for the Confederacy to defend at the outset of the war (perhaps with the exception of New Orleans and the mouth of the Mississippi) was the narrow corridor where both the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers cross from Kentucky into Tennessee. A Union army at liberty to use the rivers here would be able to freely penetrate into Central Tennessee, threatening to not only overrun the heartland of the state (and advance directly to Nashville) but also outflank defensive positions to the east along the Mississippi - positions like Polk’s base of operations at Columbus. While Polk was setting up shop in Columbus, Grant moved east from Cairo to the little town of Paducah - a seemingly trivial little settlement, except that it sat at the confluence of the Ohio, Cumberland, and Tennessee rivers, and thus gave Grant the ability to run his gunboats in any direction he pleased.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.