Soviet Operational Art: Troubled Beginnings

The History of Battle: Maneuver, Part 12

One of the many peculiarities of the Second World War was the extent to which the defeated Germans were allowed to write the history. The rapid onset of the Cold War after the fall of Nazi Germany transformed the Soviet Union from ally to adversary, and sparked interest in the German experience fighting the Red Army. The bevy of memoirs and material from former Wehrmacht officers, combined with the secrecy of the USSR, ensured that for many years the only story of the Nazi-Soviet War being told was the version told by the Germans.

In this version of the story, the Red Army was a product purely of size - human waves, hordes of crudely built tanks, and such an overwhelming storm of bio-mechanical mass that it rolled over a vastly more skilled and modern Wehrmacht. Later, however, western study became aware that the Red Army also had an extremely technical and systematized operational doctrine known colloquially as “Deep Battle”, and furthermore it became apparent that by the end of the war the Red Army had turned this doctrine into a highly lethal system that was able to roll over Japanese and German armies alike with apparent ease.

There are, then, two Red Armies. One is the slavish human steamroller which hurls men by the million against the enemy, and the other is a highly proficient and sophisticated force with an extreme degree of systemization and doctrine. The former is scorned, the latter is virtually fetishized.

These schizophrenic views of the Red Army reflect only that armies are learning institutions. The Red Army of 1941 was indeed highly wasteful of men (though not intentionally) in that it tended to be operationally clumsy and incapable of deft maneuver or effective combined arms fighting. It was led by an inexperienced and politically paralyzed officer corps. The experience of fighting the Wehrmacht for four years was bound, therefore, to leave an indelible impression and teach important lessons (however costly), and by 1945 that same Red Army had become an immensely competent and monstrously powerful force.

The process of becoming, and of transforming abstract operational theories into battlefield realities was horribly painful, and until 1943 the Red Army would be painfully groping its way along the learning curve, searching for something that could be properly called “operational art.” For the millions of Soviet soldiers who died in the first years of the war, it could seem as if the Red Army was trapped in its own search for doctrine.

Politics By Other Means: The Soviet Context

Military institutions are a product of the social and political substrate which creates them, and by extension a window into that same substrate. It is perhaps no surprise, therefore, that the Red Army was a unique institution which, just like the Soviet Union, was simultaneously neurotic, inseparably wedded to doctrinal presuppositions, plagued with systemic inefficiencies, and monstrously powerful.

Armies develop doctrines and methods of warfighting as a result of their own particular admixture of historical experiences, institutional incentives and ideologies, and material constraints. The German Wehrmacht, for example, can be understood as the culmination of a longstanding Prusso-German scheme of war making - a synthesis of a modern mechanized tactical package, the preternatural battlefield aggression of Frederick the Great and his heirs, and the operational elan of the eternal genius, Moltke. The great nemesis and destroyer of this Wehrmacht, the Red Army, can in contrast be thought of as the result of an effort to reconcile Russia’s military experiences from 1914-1921 with the ideological axioms of Marxism-Leninism and Stalinism’s powers of mass mobilization.

The Red Army as an institution was the emergency creation of an infant Bolshevik regime which found itself in a state of existential crisis. An essential element of the Bolshevik rise to power had been the intentional fomenting of mutinies and desertion in the tsarist army and an incessant anti-war program. As a result, by the time the Bolsheviks took power in late 1917, the Russian army had largely ceased to exist - a fact which allowed Germany to impose the draconian treaty of Brest-Litovsk on Lenin’s government, ostensibly stripping Russia of its western rimland. When Lenin’s cabinet called the newly appointed Commander in Chief, Nikolai Krylenko, to report on the prospects of resisting the Germans, he replied simply: “We have no army.” The collapse of Germany in 1918 mercifully let the Bolsheviks off the hook for a moment, but their lack of an army was clearly not sustainable, as they soon found themselves besieged by a loosely connecting ring of anti-communist armies led by former tsarist commanders - the so-called “White Armies.”

The ensuing Russian Civil War pitted these White Armies against the newly formed Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, which was formed by a Bolshevik decree in January 1918. The Bolsheviks originally conceived of a “revolutionary” force comprised of ideologically motivated industrial workers - an armed proletariat. They quickly determined that this was not going to work. First and foremost, the proletariat in Russia (which was still an overwhelmingly rural, peasant country) was simply too small, and secondly it quickly became apparent that a revolutionary mindset - while admirable - was insufficient to win a modern war, and military expertise was needed.

The Red Army, therefore, had to be built up in a way that was ideologically repulsive to Lenin and his party. The manpower base would have to be drawn not from urban workers, but from peasants (an ideologically suspect class at best), led by experienced military officers. Such officers could only be acquired in the short term by calling up former Tsarist officers, who were termed “military specialists”. That such “specialists” were needed was beyond dispute, but they were inherently untrustworthy and had to be monitored by the party watchdog commissars which honeycombed the army. Therefore, from the outset, relations between the party and the army were strained, because the army was necessarily built from potential class enemies (peasants and Tsarist officers).

Through the relentless conscription of peasants, the Bolsheviks managed to improvise a clumsy but powerful prototype of the Red Army, which succeeded in defeating the White Forces. Fighting across a wide theater which ranged almost the entire breadth of the Russian perimeter, the Red Army conducted sweeping operations, shuttling large forces by rail, and successfully brought most of the old Tsarist empire under Bolshevik control. In Poland, however, they ran into problems. The newly formed Polish state invaded Ukraine in 1919, aiming to push Poland’s borders far to the east while Russia was in a state of chaos. A Red Army counteroffensive drove the Poles out and pushed all the way to the gates of Warsaw. Here, on the Vistula, the Reds were defeated on a narrow front with high force concentration, finding that they were unable to penetrate the Polish front.

In Poland, the Red Army had run into its own little version of the western front - deep and congested defenses which defied penetration, exploitation, and movement and frustrated the previous pattern of operations which had led to success in the more conducive spaces of Russia, where the Bolsheviks controlled the rail network. There was therefore an inducement to study these particular operational problems and think systematically about war. This was amplified, however, by the ideological assumptions of the new communist government.

One of the core tenants of Marxism-Leninism - an outgrowth of dialectical materialism - is the assumption that most human endeavors unfold themselves to scientific enquiry. Operating on this assumption, the Red Army would in time systematize the study of war and create an extremely technical lexicon of terminology. The results, like many of the Soviet Union’s works, were somewhat paradoxical - being both groundbreaking and extremely rigid. The body of Soviet work on military art is without doubt both deep and cogent. James Schneider, a professor at the US Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies, wrote that “The single most coherent core of theoretical writings on operational art is still found among the Soviet writers.” No small thing for a distinguished cold war adversary to admit.

The Soviet determination to systematically study military operations granted them an advanced insight into the changing nature of operations. They insisted that “bourgeois military science” could never grasp the changing nature of war, and blamed this for the general catastrophe of the Great War. The other side of the coin, as it were, or the downside of Soviet modes of scientific inquiry, was a deep attachment to doctrine. Because there was an implicit assumption that war was fundamentally open to rational inquiry, it was in turn implied that military affairs could be systematically or even formulaically managed. This created a tendency towards rigidity and “by the manual” war-making, which strictly prescribed all manner of regulation front densities, deployment schemes, and meticulous planning - the antithesis in many ways of the German notion of independent field commanders improvising on the basis of opportunity and aggressive instinct.

This tendency towards rigid doctrine meshed well with the developing Stalinist system and its metastasizing control apparatus, and would contribute to the sclerotic command and control systems that led the Red Army to catastrophe in 1941. However, the Red Army undoubtedly grasped one critical point that the Germans did not understand.

The kernel of the Soviet operational art was found in the first place in the Red Army’s notion of “successive operations”. In many ways, this ran counter to the German desire to wage decisive battle. Soviet thinking instead was premised on the assumption (based on Great War and Civil War experience) that it was foolish to plan on annihilating the enemy army in a single decisive operation. This was a total rejection, in other words, of “Schlieffen Plan” style thinking. Instead, early Red Army theorists argued that the key to victory was the ability to wage a sequence of connected or chained operations, feeding prepared second and third waves (what the Soviets called “echelons”) along the same axis of advance.

Sergey Sergeyevich Kamenev, one of the first commanders of the Red Army and one of its earliest theorists, put it this way:

In the warfare of modern large armies, defeat of the enemy results from the sum of continuous and planned victories on all fronts, successfully completed one after another and interconnected in time… The uninterrupted conduct of operations is the main condition for victory.

Mikhail Tukhachevsky, who commanded Soviet forces in Poland, derived similar conclusions from his own experience, and argued that “the impossibility on a modern wide front of destroying the enemy army by one blow forces the achievement of that end by a series of successive operations.” He would later add:

“The nature of modern weapons and modern battle is such that it is an impossible matter to destroy the enemy’s manpower by one in blow in a one day battle. Battle in a modern operation stretches out into a series of battles not only along the front but also in depth until that time when either the enemy has been struck by a final annihilating blow or when the offensive forces are exhausted.”

Another contemporary officer, Mikhail Frunze, argued that future wars would be “long and cruel”, and would require the mobilization of the country’s full reservoir of resources. He therefore called for the “militarization of the work of all civil apparatus” and a “definite plan for converting the national economy in the time of war.”

Already by the late 1920’s, therefore, the Red Army was clearly converging on many of the key concepts that it would put into practice in the 1940’s. In particular, there was an emerging consensus that offensive operations would have to be sequenced (that is, chained together along the same axis) with prepared second and third echelons that could follow the first attack package down the same axis of advance. This was given further life by Tukhachevsky’s instance that future wars would require massed tank action, on the order of many thousands of vehicles, to give the offensive adequate fighting power.

In February 1933, the Red Army published a new directive titled Temporary Instructions on the Organization of Deep Battle. This, for the first time, installed the iconic phrase in the technical Soviet military vocabulary and heralded the emergence of the famous Soviet doctrine - the communist corollary to blitzkrieg.

But what exactly is Deep Battle? Like Blitzkrieg, the term has widespread cachet but is not always well understood. 1936 regulations issued by Tukhackevsky’s staff described it thusly:

Simultaneous assault on enemy defenses by aviation and artillery to the depths of the defense, penetration of the tactical zone of the defense by attacking units with widespread use of tank forces, and violent development of tactical success into operational success with the aim of the complete encirclement and destruction of the enemy.

This is not very helpful. This sounds like little more than a broad description of mechanized combat and not particularly different than the German approach to war. There were, however, critical distinctives - particularly a later note from the 1936 regulations which stipulated “The enemy is to be paralyzed in the entire depth of his deployment, surrounded and destroyed.”

That phrase - “the entire depth of his deployment” is closely related to the argument that tactical success would be developed into operational success, and in particular represents the established Soviet emphasis on “successive operations”, with multiple echelons or strike packages carefully prepared so that a sequence of waves could be pumped into the breach.

The distinction between German operational sensibilities and the theory of Deep Battle might be characterized this way:

German operations were frontloaded and governed largely by initiative and organic momentum. The fighting power - in particular panzers and motorized elements - was concentrated in the breaching units, and subsequent rollouts and thrusts were at the discretion of the field commander, who enjoyed great independence (at least up until December of 1941).

Soviet operations, in contrast, were both meticulously planned and partially backloaded, in that large packages of mechanized forces (including tanks) were organized in the reserve echelons, which were then sequentially fed through the breach to exploit the axis of advance and propel the attack further along.

Therefore, while German operations were preoccupied with breaching enemy lines and destroying enemy forces and operational targets, Deep Battle aimed to exploit as deep into the enemy rear as possible, with the intention of hopefully reaching enemy operational or even strategic reserves and overrunning combat sustainment infrastructure far in the enemy rear.

Aesthetically, the impression of a German operation is that of pincers - separated armies maneuvering towards each other to catch an enemy mass in the middle. The impression of a Soviet operation is rather more like a chisel, being hammered repeatedly into the same spot to break the enemy structure open.

At the tactical level, what this looked like (at least in an idealized form) was something not altogether different from the German mechanized package. A key strand of prewar Soviet thinking emphasized “shock armies” - special army sized formations that were overloaded with additional artillery and combat engineering units, to maximize breaching power. Such shock units by convention formed the first echelon of a textbook attack, while the 2nd echelon would be lighter on artillery but heavier on tanks and motorized forces. Thus, the gun-heavy first echelon formed the breaching unit, while the more mobile second echelon would grant exploitation and destroy the units bypassed by the first echelon.

Augmented by close air support and supported by paratroopers inserted at carefully selected points, this was a system of warfighting designed to overcome the congestion and indecision of the Great War, by fully leveraging industrial warfare into a powerful and sustained assault. Ultimately, its promise lay in the potential of echeloned attacks to power the assault to the operational depth - sucking not just the enemy’s frontline forces, but his entire operational grouping including reserves and rear area infrastructure into the fray. This offered the potential to transform local (tactical) successes into operational victories that could collapse entire sectors of the enemy front.

Armies, of course, exist in political contexts, and in this case the political context was that of Stalinism. Much of the Red Army’s early leadership and preeminent theorists would fall victim to the Stalinist purges of 1937-38 - most notably Tukhachevsky. With a general hunt for enemies, saboteurs, spies, and plotters (real or imagined) underway, some Soviet functionaries sensed an opportunity to advance their own careers. One Artur Artuzov had risen to become deputy head of military intelligence in the mid 1930’s, before an unceremonious demotion to a low level archival job. Perhaps out of bitterness, or merely out of a desire to return to the party’s good graces, Artuzov wrote a letter to the NKVD head, Nikolai Yezhov, claiming that he had evidence of a plot by the military brass to overthrow Stalin and the politburo. Stalin responded by having Artuzov arrested (on the grounds that he could only know of such a plot if he were a co-conspirator) and tortured. On May 22, Tukhachevsky was arrested.

Part of Tukhachevsky’s problem was that his general profile and demeaner were objectionable. His family background was aristocratic, and he was possessed of significant swagger and self assurance (he remarked as a young man that he would either become a general by age 30 or die in combat). He was competent, he knew that he was competent, he liked beautiful women and expensive things, and he didn’t mind people knowing it. This was all rather alarming to communists, and in particular Stalin, who believed that the officer corps was by nature a threatening breeding ground for counter-revolutionary attitudes - every good revolutionary keeps an eye out for Napoleon.

It took the NKVD interrogators four days to break Tukhachevsky down. His confession was splattered in his own blood: the stains remain on the pages to this day.

Tukhachevsky’s confession – to crimes he did not commit – became the launching point for a widespread slaughter of the upper military ranks. Virtually the entire high command of the Red Army were beaten until they confessed to working for fascism. The carnage inflicted on the Red Army in 1937-38 was astonishing. Some 33,000 out of 144,000 officers were removed from their posts in total. But the damage was the most severe at the highest ranks. The Red Army had 186 division commanders, of whom 154 were claimed by the terror, to go along with 8 out of 9 admirals, 13 out of 15 front level generals, and 3 out of 5 marshals. Taken together, this means that in a two year period Stalin killed, imprisoned, or exiled 83 percent of his highest ranking military officers. The tragic irony, of course, is that there was no military conspiracy, because if there had been, the military brass might have attempted a coup to save their own lives – after all, the Red Army was the only institution in the USSR with the firepower and disciplined hierarchy to fight back against the NKVD. But because they were, in fact, loyal communists, they simply groped about in blind confusion as Stalin slaughtered them.

With Tukhachevsky’s corpse lying in an unmarked pit outside of Moscow, his ideas naturally fell into disarray and the Red Army entered a state of institutional sclerosis and decay precisely as war was approaching, although critical and talented minds like Zhukov, Konev, and Rokossovsky were lurking in the wings. The purge of the officer corps occurred at the same time that the army was expanding rapidly, from some 1.5 million active duty troops in 1937 to over 5 million by 1941. This massive expansion required the rapid promotion of officers, precisely as huge numbers were being purged and the remainder bludgeoned into rigid inactivity.

Furthermore, the execution of key theorists like Tukhachevsky led to the abandonment of many of the Red Army’s best ideas, and deep battle was abandoned in favor of parceled out tank brigades in an infantry support role. While Tukhachevsky remains the most famous victim of the officer purge, a whole slew of talented and insightful thinkers were destroyed. Men like Alexander Svechin and Ieronim Uborevich, who might have otherwise earned name recognition amid distinguished military careers, are now little more than obscure footnotes and names on execution lists in the NKVD archives.

The purge therefore ensured that the Red Army would go to war in a state of doctrinal confusion and unsophistication, led by a an officer corps made up in the lower ranks of overpromoted young men, and in the upper ranks of untalented Stalin favorites. When the Germans invaded in 1941, one of the key army group commanders was long-time Stalin supporter Semyon Budyonny, who had explicitly stated that he believed tanks were a passing fad that would be subordinate to traditional cavalry. Hardly the ideal choice to go toe to toe with the German panzer package. The result was the tragically predictable catastrophe of 1941. Dreams of deep battle and massed tank forces were shelved, and the mission became mere survival.

Tempo: Kharkov, 1942

In virtually every sense, 1941 was an utter disaster for the Red Army. From June through the end of November, essentially every major operation - both defensive and counteroffensive - ended in spectacular defeat and astonishing losses. Beginning in December, battlefield initiative passed to the Red Army for a time owing to the general exhaustion and attrition of the Wehrmacht, and the Soviets were able to conduct a general winter offensive. While the most famous element of this effort is of course the counterattack at the gates of Moscow, the Red Army in fact went on the attack all across the enormous front and managed to reverse some of the Wehrmacht’s territorial gains.

From an operational perspective, the Soviet Winter Offensive was rather simplistic and had no resemblance to the carefully planned and echeloned operations which Tukhachevsky and his supporters had dreamed of. By December, the Red Army had neither the time nor the resources to meticulously plan and prepare a proper echeloned attack - they simply threw a string of available armies, invariably under-equipped and under-prepared, at the Germans to take advantage of the Werhmacht’s state of exhaustion. By April, these attacks had achieved variegated levels of success (at the cost of high casualties) and created a strange, undulating frontline which settled wherever combat happened to run out of energy.

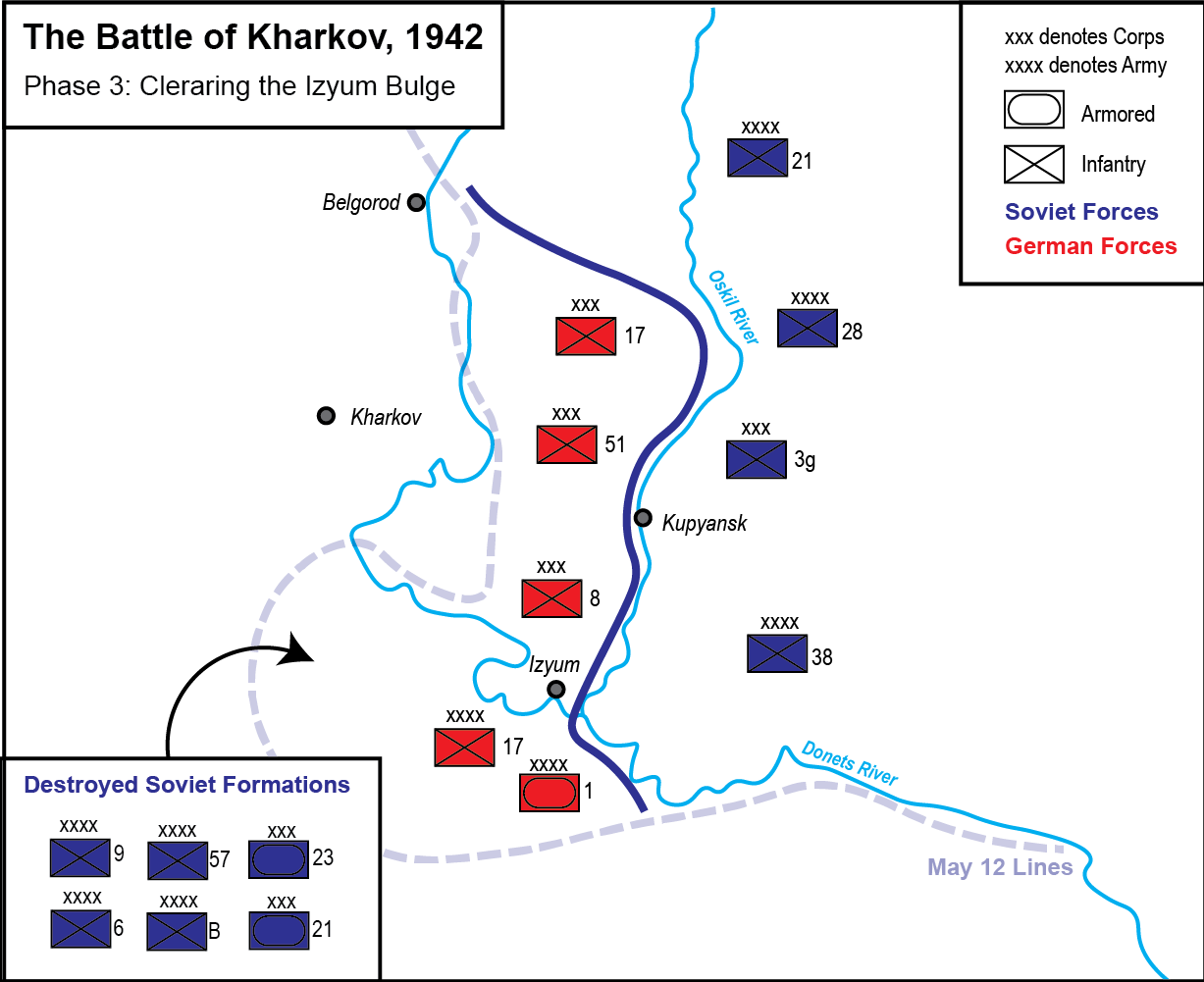

For Stalin and Hitler, surrounded by their staff officers and huddled over their situation maps hundreds of miles apart, one particular spot on this bizarre frontline stood out. This was a bulge, or salient, which had formed around the city of Izyum in the southern section of front. The Soviet winter offensive had successfully captured a bridgehead over the Donets River, south of the major industrial city at Kharkov. By happy circumstance, the Red Army was also clinging to a narrow bridgehead upstream, north of the city.

The winding, irregular nature of the front here created operational opportunities that were extremely tempting to both armies, according to both their doctrinal disposition and broader strategic directions.

The Red Army’s planning in 1942 was centered on the idea, largely driven by Stalin, that German operations that year would be focused on a renewed effort to capture Moscow. Zhukov remembered:

Stalin believed that in summer 1942 the Germans would be able to carry out large-scale offensive operations… he was above all concerned about the Moscow axis where over 70 German divisions operated.

In March, Stalin issued orders that the commanders of the various Red Army Fronts (again, this being the Soviet equivalent of an Army Group), should conduct a general evaluation of their sectors and make suggestions as to how they could conduct operations that would support the overall strategic imperative to defend Moscow. The commander of the Southern Front, Marshal Timoshenko, opted to stretch these instructions to justify a renewed offensive. Timoshenko had a rather disastrous combination of traits. He was aggressive and optimistic - qualities that synergized poorly with his overall mediocre talent and his good relationship with Stalin. Timoshenko wanted to attack, and believed the Izyum salient was an ideal spot.

Timoshenko and his team crafted a proposal for Stalin which argued that going on the offensive in the south would disrupt German development, throw off their timetables, and force them to redirect reserves away from Moscow. Stalin considered these arguments, and ultimately agreed to adopt an operational plan for 1942 in which “Simultaneously with the shift to a strategic defense”… the Red Army would conduct “local offensive operations along a number of axes to fortify the success of the winter campaign, improve the operational situation, to seize the strategic initiative and to disrupt German preparations for a new summer offensive.” This was an ambiguous and open ended strategic approach which gave Timoshenko carte blanche to go all in on the attack. Marshal Alexander Vasilevsky, Stalin’s Chief of Staff, would later ruefully remember that the decision “to defend and attack simultaneously turned out to be the most vulnerable aspect of the plan.”

Moscow had never been the German strategic objective in 1942. Confronted with the prospect of a global war against the Anglo-Americans *and* the Soviet Union, German planning for 1942 was heavily preoccupied with acquiring access to the raw materials, especially oil, which would allow Germany to wage a prolonged, global war. The centerpiece of Germany’s efforts for the year would be Case Blue: a powerful offensive to the southeast to capture the Soviet oilfields in the Caucasus. Along the way to the oil fields, the Wehrmacht hoped to trap, encircle, and destroy all the Red Army forces west of the Volga River.

Unlike Operation Barbarossa, which had pretensions of winning the war outright in a matter of weeks, Blue was drafted in recognition of the fact that a short war was no longer on the table, and that to survive a protracted global struggle Germany needed oil. “The operations of 1942 must get us to the oil,” admitted Keitel, head of the armed forces high command. “Unless we achieve that, we shall not be able to conduct any operations next year.” A sobering thought – especially for a German army that lived and died based on its ability to wage mobile warfare.

In the spring of 1942, however, what mattered most was that the Wehrmacht was massing units in the south in preparation for Blue. Timoshenko’s offensive at Kharkov, therefore, swung directly into the sector of the front where the Germans were preparing units for an offensive of their own.

The synchronicity of the operational plans was remarkable. Not only were both armies preparing for an offensive in the south, but both had specifically chosen the Izyum salient as the specific sector to begin with. Timosheno planned to launch his armies out of the salient, envelop and capture Kharkov, and then run the Germans back towards the Dnieper. The Germans, simultaniously, were planning Operation Fredericus - a rather textbook pincer movement to cut off the Izyum salient and trap the Soviet armies inside.

Yet the coincidences ran even deeper than the armies simply targeting the same sections of front. The start dates for these two operations were planned for a mere six days apart - Timoshenko planned for May 12, and the Wehrmacht for May 18. Even more remarkably, the most powerful units in each army’s order of battle for these operations was the 6th Army. The spearhead of the Soviet attack would be the 6th Army under General Gorodniansky, and it was lined up directly across from the German 6th Army under General Friedrich Paulus.

On May 8, Field Marshal Bock - the new commander of Army Group South - speculated that “the Russians might beat us to it and attack on both sides of Kharkov.” Hitler, however, thought this was silly: “such strong German forces are now in the process of assembly that the enemy is bound to be aware of this and will be careful not to attack us there.” Timoshenko, however, was not aware, and so blundered into a colossal operational trap.

The 1942 Battle of Kharkov was a curious thing. It ended in an unmitigated disaster for the Red Army - a result which has generally led the entire thing to be written off as another painful and irredeemable turn in the long Soviet learning curve. However, the disaster that unfolded at Kharkov was due to German supremacy at the operational level. At the tactical level, the Red Army demonstrated that it had grown leaps and bounds since June 1941 and was on the road to an effective method of offensive warfare.

On January 10, 1942, Marshal Zhukov had issued Stavka Directive #03. This order, though easy to miss amid the general drama of the winter battles around Moscow, in fact signaled a major revision of Soviet operational practices and a return to the familiar prewar concepts of Tukhachevsky. Directive #03 resurrected the “shock group” as the principle breaching unit, and instructed that attacking units ought to concentrate their forces on very narrow frontages. The regulation attacking front for an army was a mere 15 kilometers. Furthermore, the composition of shock groups was a turn away from the massed infantry units used by the Soviets in 1941, and featured heavy concentrations of tanks, artillery, and ground support aircraft.

In keeping with this emerging doctrine of highly concentrated combined arms operations, Timoshenko’s Kharkov operation concentrated large shock groups with enormous fire support - in some sectors, up to eighty artillery pieces per kilometer. When the opening artillery and air barrage began on May 12, the Red Army achieved total tactical surprise. The initial impression of the German defenders in frontline posts, surely, was that the shock groups lived up to their name. The Red Army had never hit so hard - a veritable storm of fire precipitated the approach of ground units. In the southern sector, the shock group attacking out of the Izyum salient tore a huge hole in the German lines and rendered the German 294th division almost completely combat incapable within the first day.

On the tactical level, this Red Army was as different from its 1941 self as night is from day. The attack was far more concentrated, far better supported by artillery and air assets, and comprised of a far better mix of infantry and armor than anything the Germans had been faced with the previous year. The shock group proved capable of punching holes in German defenses - the question was now how to transform this into an operational success.

One lesson about warfare on this scale which is clearly taught by the experience of the two armies at Kharkov is the generally confused an incomplete nature of real time intelligence, and the possibility for both sides to be in some state of panic simultaneously. On the Soviet side, Timoshenko had to be pleased with his initial progress. By day three, his northern pincer was only ten miles from the outskirts of Kharkov. But some things were not right. Disturbingly, there were panzer divisions observed loitering on the flanks that were not supposed to be there, and the Germans were moving in reinforcements that were not expected (this is because the Wehrmacht was massing forces for its own offensive, and so had unexpected reserves close at hand). While Timoshenko hesitated, puzzling over the unexpected German forces, Bock was at German Army Group South headquarters desperately trying to galvanize a response from Hitler and the high command. By May 15, the situation map was such that nobody was truly comfortable.

In such an unstable state, the advantage flowed to the side with the calm, elan, and decisiveness to take control. Soviet doctrine had prepared the cognitive basis to deal with such a situation - it was time to send in the second echelon. Timoshenko had just such an echelon, comprised of two tank corps, which ought to have been inserted promptly (probably beginning early on May 14) to reinvigorate the Soviet advance in the face of German forces and give the fresh combat power to push the Soviet pincers closed.

Unfortunately, Timoshenko hesitated in the face of the uncertainty now present on his situation maps, and this ensured that the second echelon would not arrive in time. The opening shock group had pushed the frontline forward via kinetic action, which meant that the second echelon needed to trundle up roads that were already scarred by battle (littered with debris and shell holes) to reach the actual line of combat. The time delay involved in actually getting the second echelon to the front meant that they needed to be ordered forward promptly, if not preemptively. Hesitation proved fatal. The Soviet General Staff report would later conclude:

By the end of 14 May, the second-echelon tank corps (with 260 tanks) and rifle divisions were a long way from the front line. General Kuzmin's 21st Tank Corps was forty-two kilometers away from 6th Army's forward units; General Pushkin's 23rd Tanks Corps was twenty kilometers away, and the 248th and 103rd Rifle Divisions, which comprised 6th Army's second echelon, were twenty to forty kilometers away. Such a separation of second-echelon forces and forces of the echelon for developing success made difficult their timely commitment into battle, which was urgently dictated by the situation.

While Timoshenko hesitated, the Germans acted.

The crux of the matter was fairly straightforward. Operation Fredericus had originally planned to attack the base of the Izyum salient with a pincer movement and pinch off the Soviet troops inside. By attacking out of the salient, the Soviets had theoretically made this easier (since, by attacking westward, they were moving forces away from the German target at the base of the bulge). However, Fredericus could not be enacted as planned because the Soviet attack had smashed right into the force that was intended to form the northern pincer (German 6th Army). The solution to this operational problem was to rush reinforcements to the scene to provide a proper attack package to launch Fredericus.

Here, then, the enormous importance of German decisiveness and quick decision making became apparent. While Timoshenko dithered over where and when and how to commit his second echelon, the Whermacht brought a surge of fighting power to the scene. Units had already been amassing in the south for Case Blue, and a whole slew of these were now rushed to the Kharkov axis - 24th Panzer division was the first to arrive, followed by reinforcing infantry divisions. Perhaps even more importantly, the 8th Fliegerkorps (Air Corps) was en-route: a powerful Luftwaffe formation that brought German aircraft strength in the area up to nearly 600 planes. This was a huge surge in fighting power, and Fredericus was given the green light to start on May 17.

When that day arrived, Timoshenko’s huge fighting mass was still slogging its way westward, dishing out serious punishment to the units that Germany had put in its path. This was not a comfortable experience for the Wehrmacht at all. The Soviet attacking group was a hugely powerful force which integrated its arms much more efficiently than the Red Army of 1941 had. This Soviet grouping had a problem, though: the Germans had large forces now amassed to the south and northeast, firmly in its rear, prepared to launch Fredericus.

By the end of the 17th, 1st Panzer Army under General Kleist had launched off its starting lines around the city of Slavyansk and torn a huge hole in the Red Army’s southern flank guarding the “neck” of the salient. All the Soviet forces then attacking westward faced immanent annihilation if they did not immediately break off the attack and withdraw back towards Izyum. Here, again, Timoshenko proved indecisive in a critical moment. Rather than ordering a withdrawal, he actually sent additional reserves in to reinforce his attack (a useless gesture at this point), and it was not until the 19th that he approved a withdrawal by his frontline units. By this time it was far too late.

The ensuing debacle encapsulated much of this war - German elan, Soviet command and control difficulties, and capricious cruelty. By May 21, the “opening'“ of the Izyum salient had been narrowed to just 8 miles wide by the German pincers. A handful of bridges across the Donets river in this narrow gap now represented the only line of communication, supply, or retreat for the massive Soviet forces in the pocket. While the Germans pounced on these bridges and captured them, an enormous traffic jam was beginning to the west. Timoshenko’s withdrawal order had gone out to the units at the forefront of the attack - 6th Army and Army Group Bobkin. His second wave, consisting of his two Tank Corps, was still moving west to reinforce the attack - somehow, these units had not received the withdrawal order. On May 21, as the Germans closed off the neck of the pocket, Timoshenko’s retreating 1st Echelon ran into his advancing 2nd Echelon - a traffic jam inside an encirclement.

It took the Germans a week to liquidate the Soviet forces in the pocket, which after all were huge and continued to fight as best they could. Red Army losses were in the end enormous. The entirety of 6th and 57th Armies, Army Group Bobkin, and the 21st and 23rd tank corps were wiped out inside the pocket, and 9th Army (the unfortunate unit which had been defending the entrance to the bulge) was badly mauled. All in all, nearly 280,000 men were lost, along with a whopping 1,200 tanks and several thousand artillery pieces.

The autopsy on Kharkov, 1942, is rather an interesting one. It is very easy to place all the blame on Timoshenko, who was as a rule indecisive and mishandled the operation in obvious ways. Timoshenko was, to be sure, in over his head. The catastrophe at Kharkov seems to have awoken Stalin to this reality, and Timoshenko was removed from field command - but because he was one of Stalin’s favorites, he was given a symbolic post at high command (a sort of promotion into a position where he could do little harm) rather than being shot.

It is one thing to say that Timoshenko bungled the Kharkov operation and contributed to a disaster. But the particular nature of that disaster was largely not Timoshenko’s fault - rather it was foretold by the particular interplay of Soviet operational thinking and Red Army command and control disfunction.

The idea of Deep Battle was to mass sequenced echelons that could attack along the same axis, conducting consecutive operations to overcome the natural tendency of offensives to culminate. Where traditional offensives would run out of steam, the Red Army would have a second echelon prepared to keep the attack going, maintaining an attacking tempo and denying the enemy the chance to regain operational initiative.

Tempo, however, requires… well, tempo. Not a wavering indecision, and certainly not a command and control screwup which left the two echelons to crash into each other. In the particular case of Kharkov, the combination of Timoshenko’s indecision, Soviet command and control snarls, and the imperative (both doctrinal and political) to continue the attack resulted in a sort of mindless hammering, oblivious to the danger massing at the neck of the salient.

In fairness, the Red Army had shown genuine improvement since 1941 on the tactical level - as a result, this mindless hammering was very violent and immensely damaging to the German units on the other end of it, but the improved functionality of the Soviet mechanized package did not translate to operational success - just as German operational skill could not translate to strategic victory.

Above all, Kharkov was a victory of Clausewitz. The great 19th Century German theorist thought of warfare as a tripart interaction between rational calculation, violent emotion, and random chance - that is, between planning, aggression, and luck.

Soviet notions of deep battle and echeloned attacks were predicated on the idea that sustained attacks would maintain offensive tempo and deny the enemy the chance to regain the initiative. All well and good, and in 1942 Timoshenko prepare a powerful multi-echelon attack package and identified a reasonable operational target. This is rational calculation and planning. What Timoshenko lacked - and what the Wehrmacht had in spades - was a preternatural aggression, and in the critical days while Timoshenko timidly let his offensive languish, the Germans were rushing additional divisions and air assets to the battlespace.

Ideas like tempo, initiative, and continuity of the attack are useful, and can form worthy concepts or objectives. They may even be pedagogically valuable motifs in the context of a military institution. On the battlefield, however, tempo and initiative must be taken and held by the decisiveness and aggression of the entire fighting organism.

In the end, Kharkov was a demonstration of the enormous gap between doctrine and victory; between planning and the battlefield. Victory ultimately depends not only on material and sound operational planning, but also on a lithe and reactive fighting body that can pass information and orders up and down within its command structure in a timely manner. Such an army is present and in intimate contact with reality on the ground, rather than operating entirely within the abstract realm of plans and doctrine. This is why Moltke, the greatest of all the German commanders across the ages, never liked to plan operations beyond a general sketch - he abhorred the idea of becoming too wedded to “the plan”, since events on the ground and the actions of the enemy always took precedence.

At Kharkov, the Red Army very much seemed to be an army held captive by its own doctrine and plans. Facing a rapidly changing situation on the ground, with German forces massing for a counterblow, Timoshenko wavered for a bit before deciding to send the 2nd Echelon in to continue his offensive, doubling down on the attack when circumstances strongly prohibited it. He stuck to the plan, until it was too late.

The Other Foot: Operation Mars

1942 was by any reckoning a world-historical pivot. In the summer, the Japanese carrier force was crippled at the Battle of Midway (a subject for our future series on naval warfare), which all but guaranteed American victory in the Pacific - Japan’s only real hope for victory having been to shock the United States into negotiations by achieving naval airpower supremacy. 1942 is also generally understood as the “turning point” in Europe, given that the first six months saw significant German victories at Kharkov, in Crimea, and in North Africa, and the year ended with German defeat at Stalingrad (the subject of our next article). Though I argued in my previous article that the genuine “turning point” of the war, as such, was the Battle of Smolensk in the late summer of 1941 (since this was the point where Germany’s all-important panzer divisions became too attrited to finish the war), there is no denying that 1942 was the year where the strategic initiative passed firmly from the axis to the allies.

In many ways, the popular narrative structure of the Second World War fails to accurately represent both the opportunities and risks facing the belligerent parties. More specifically, Germany had “lost” the war much earlier than most people realize - by September, 1941, there was no reasonable military path to a German victory over the Soviet Union, let alone over the monstrously powerful Anglo-American-Soviet alliance. At the same time, however, actually destroying Nazi Germany and the Wehrmacht was much more difficult and dangerous than is commonly understood. Even once it no longer had a path to its own victory, the Wehrmacht had the power to make its defeat a costly proposition. For the Soviet Union, for example, the most costly quarter of the war in terms of total casualties was Q3 (July - Sep) 1943 - at a point in which the Red Army was clearly winning. Even cornered in a trap from which there was no escape, the Wehrmacht was lethal.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.