There are a handful of cataclysmic breaks in the historical timeline: upheavals so severe that they signal a wholesale course shift in the trajectory of human political development. Oftentimes these are the result of exogenous forces - human migrations and invasions external to the political subject, as in the case of the Bronze Age Collapse, the barbarian migrations which destroyed the Roman Empire, or the Mongol expansion across Eurasia. Sometimes, however, existing political structures which can superficially appear stable will collapse organically into chaos. These latter, internally generated breakages are usually called “revolutions.”

The French Revolution (1789 - 1799) ranks among the most dramatic and cataclysmic of these political breakages. The collapse of French absolutism had seismic effects which reached far beyond the borders of France itself, with the abolition of serfdom and the privileges of the nobility, a fumbling reach for participatory politics and the emancipation of the individual, the emergence of new strands of patriotic nationalism, and the first recognizable advent of secular millenarian ambitions. Many of the motifs that universally characterize modern political life, like mass political participation, the nation, and the end of arbitrary absolutist rule were clearly present in Revolutionary France, to the point where the revolution - for good or ill - is identified closely with the origin of modernity as such.

Yet for all its high minded idealism, and the frequently rosy nostalgia which reduces the French Revolution to a simplistic revolt of starving commoners against a profligate and unfeeling monarchy, the Revolution in France was also extremely bloody and terrible - it ushered in a period of extraordinary political violence and famine, and it failed utterly to provide stable governance - at least until the emergence of the singular man of the age in Napoleon.

From a geopolitical point of view, the French Revolution is fascinating for rather unexpected reasons. While the Revolution did mark a wholesale break with past political and social norms, in truth it changed the geopolitical dynamics of Europe very little. For a century, European affairs had been driven by the French Problem - that is to say, France’s preponderance of power and its outward drive, which repeatedly brought it into conflict with vast enemy coalitions; in the inverse, France itself had long struggled with how to manage the dual strains of both its extensive land commitments and the difficulty of waging naval-colonial war against its offshore rival in Britain.

The Revolution, rather than bringing an end to the French Problem, in fact only served to intensify it. Revolution brought extensive new powers of mobilization to France, with mass political participation in turn spawning expansive conscription of fighting men (the Levee en Masse) while the churning of the French officer corps brought young and dynamic talents into command - Napoleon chief among them. While the peculiar social form of the Revolution was unprecedented (and terrifying to Europe’s remaining absolutist monarchies), there was nothing particularly new about France going to war with the continent - except this time, the size of her armies and the intensity of the warfare had been greatly increased. After the stabilization of France under Napoleon’s guardianship, the geopolitical dynamic of Europe returned to something approximating its pre-revolutionary norm, with governments in Austria, Prussia, Russia, and elsewhere forced to mediate between the immediate threat posed by French land power and the looming, global power of Britain. As late as 1812, there were fierce debates in many European capitals as to just which of the western powers - Napoleon and his grand armee, or the British and their spectacular navy - posed the greater threat.

One of the more peculiar aspects of this warfare, and a subject of our interest here, is that the Revolution had markedly different effects in France’s army and navy. French fighting power on land was magnified greatly by the effects of the Revolution, and the power of the French Army - in combination with his own singular genius - would bring Napoleon tantalizingly close to the ultimate dream of continental hegemony. On the oceans, however, the Revolution created a drastic setback for the French Navy, for reasons we will elucidate momentarily. The French Navy, which had made a remarkable comeback under the latter Bourbons, was greatly weakened by the Revolution and entered the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars in a shaky and parlous state.

This would have disastrous effects for France, because France’s revolutionary wars coincided with the life of one of history’s rarified military geniuses: not Napoleon (though he was, to be sure, a genius), but Admiral Horatio Nelson. The name Nelson is undoubtedly very famous - practically synonymous with Britain’s era of global naval supremacy. The British naval apparatus was, by the time of the French Revolution, already a well oiled machine, and when general war again began on the European continent, it was inevitable that the Royal Navy would be London’s primary lever of kinetic power against the resurgent French. In Nelson, it found its ultimate practitioner - a commander with a rare mixture of instinctive tactical aggression, operational dexterity and imagination, and intangible human qualities of leadership.

The land wars that ravaged Europe at the dawn of the 19th Century will always be known by the name of France’s own military dynamo. They were, in almost every sense, Napoleon’s wars. The war at sea, however, played its own crucial role in the outcome, and it was here that Napoleon’s military genius found its limits. Napoleon was the land general par excellence, but the sea belonged to Nelson.

The Revolution at Sea

Enumerating all the social, economic, and political upheavals originating in the French Revolution would be a monumental task. To be sure, there is no shortage of historical literature on the watershed event of modernity and the great uncorking of social forces that could not be rebottled even by decades of war. Here we will confine ourselves to a brief meditation on the ways that the French Revolution affected France’s state power, both in a general sense and more particularly as it relates to the navy.

Revolution had the general effect of massively increasing France’s capacity for armed power projection, by eradicating longstanding constraints on the size and conduct of her armies. The fall of the Bourbon regime opened the way for the first time to an ethos of mass politics and national participation, which made it possible to conduct a mass mobilization of fighting men. Segregating the armed forces and the civilian populace was a longstanding concern of Europe’s monarchies, since the army was always intended to be a bulwark against popular rebellion. Revolution made such concerns obsolete and empowered the popular government to raise armies that dwarfed enemy monarchist forces.

France’s ability to mobilize enormous forces was augmented by the onset of war with Central Europe’s monarchies, which created a permanent sense of siege and emergency. The arrival of the levee en masse, gave France sprawling forces which exponentially increased her potential for power projection. A 1773 proclamation, which is popularly reprinted in practically every history of the era, stated:

From this moment until such time as its enemies shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the services of the armies. The young men shall fight; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothes and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn linen into lint; the old men shall betake themselves to the public squares in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic

There is, of course, an aura of melodrama and exaggeration to all this, with the exhilarating notion of the entire nation mobilizing in a fight for survival, but the numbers are difficult to argue with. By 1794 the French had some 1.5 million men under arms, most of them well motivated by the newfound sense of patriotic mass politics. In early Revolutionary battles like Fleurus and Wattignies, it was not uncommon for the French to bring a nearly 2 to 1 advantage to the field.

The other crucial aspect of the Revolution from the perspective of the army was the astonishing churn of the officer corps. Most of France’s senior officers were of aristocratic extraction and were therefore swept quickly out of their posts, to be replaced by rapidly promoted field-grade officers. The result was that French military leadership tended to be much younger than their adversaries - great generals of the Revolutionary Armies, like Napoleon, Étienne Macdonald, and Jean-Baptiste Jourdan were still in their 20’s when the Bourbon government fell.

On the whole, then the Revolution had the effect of rapidly expanding France’s force generation and promoting a new caste of younger, more dynamic officers into command to replace the stale aristocratic officer corps. The early years of Revolutionary warfare therefore saw a wave of stunning French victories, with the French overrunning the low countries and achieving military objectives that had stymied the Bourbons for generations.

In the navy, however, an entirely different dynamic emerged. The particularities of naval combat make it immune to the factors that made Revolutionary France’s land forces so powerful. In the first place, the navy cannot be exponentially expanded overnight simply by declaring a levee of manpower. Naval power projection relies - quite obviously - on capital intensive and immensely complicated engineering projects which we call “ships.”

Furthermore, Revolutionary efforts to remove Aristocratic officers and instill an egalitarian, revolutionary spirit in the armed forces were disastrous for the French navy. A October 1793 decree ordered the Minister of Marine to provide a list of all officers whose loyalty to the Revolutionary Regime was considered suspect, and the subsequent purging of officers created an institutional cancer in the service. Navies rely on strict, untrammeled discipline - an absolute necessity given the complex coordination that it takes to operate a sailing warship and the stresses imposed on hundreds of men confined in close quarters with one another. Mutinies became frequent, and a marked deterioration in discipline was observed. This had further knock-on effects, with many experienced sailors and petty officers growing disgusted with the indiscipline and leaving the navy to work on merchant ships. Meanwhile, attempts to promote new officers frequently went badly, with the Revolutionary apparatchiks in charge of these decisions lacking the technical knowledge of sailing to judge candidates correctly. As Admiral Villaret Joyeuse put it: “Patriotism alone cannot handle a ship.”

By far the worst injury imposed on the navy, however, was the 1792 decision to abolish the Fleet Gunners Corps. This was a corps of some 10,000 men, specially trained in naval gunnery, which provided the backbone of French fighting power at sea. In their place, the Revolutionary Regime opted to staff naval batteries with an amalgamation of general artillerists, trained to roughly the same specification as the artillery crews of the army, and commanded by artillery officers, rather than naval officers. The motivation for this change, rather bizarrely, seems to have been indignation at the fact that naval gunnery crews comprised their own elite corps, segregated from the land artillery. The President of the National Convention, Jeanbon Saint-André, complained:

In the navy there exists an abuse, the destruction of which is demanded by the Committee of Public Safety by my mouth. There are in the navy troops which bear the name of “marine regiments.” Is this because these troops have the exclusive privilege of defending the republic upon the sea? Are we not all called upon to fight for liberty?

In essence, the special training and elite status accorded to Fleet Gunners Corps made them an anathema to the egalitarian ideals of the Revolution, and they were summarily abolished to be merged with the artillerists of the land forces. This, obviously, would have terrible effects on French combat effectiveness at sea, with the new gunners unaccustomed to shooting at moving targets from a moving and pitching firing platform. The loss of accuracy and proficiency was particularly problematic given the French combat methodology, which favored firing on the uproll of the ship to smash the enemy’s fragile rigging - in contrast to the British, who aimed at the larger and more accommodating target of the enemy hull and gun banks. Thus, French naval gunnery - which had previously been world class and a major source of their fighting strength at sea - was severely crippled by political choices at the onset of war.

Much of the surviving French naval establishment was well aware of this self-imposed crippling, but the political climate of the day left them with nothing to do but issue unheeded warnings. Admiral Morard de Galles wrote in 1793 that “The tone of the seamen is wholly ruined. If it does not change we can expect nothing but reverses in action, even though we be superior in force.” The latter clause is particularly important. The Bourbons left an unenviable legacy in France, with the country’s economy and finances in tatters, her political body inflamed by resentments, and her borders surrounded by enemies. The navy, however, was in remarkably good shape. The latter Bourbon navies had lavished great attention on the shipyards and naval bases, after much neglect, and had won important victories over the Royal Navy in the American War. With the British fleet dispersed over much of the earth to safeguard her far flung colonial lifelines, the French had every reason to expect fair or even favorable fights in the near waters of the Channel, the North Atlantic, and the Mediterranean. The Revolution upended this calculus, even as it upended the world.

When war broke out in full force in 1793, the naval theater lay largely dormant for the first year, largely due to the sorry state of the French fleet, the more pressing emergencies on France’s land borders, and the surprise capture of Toulon by a British task force, which put France’s main naval base in the Mediterranean under occupation. The loss of Toulon in December 1793 to Napoleon Bonaparte (which left fifteen French ships of the line intact) was a major disappointment to the British, who hoped to keep the French navy bottled up for the duration of the coming war, but the fact remained that there was initially little reason for the French, pressed about on all their land borders, to seek a fight at sea.

French energies were directed inwardly, towards a major land war which was initially defensive in nature. With France feeling itself to be in a state of siege, there was little interest in dispatching the fleet for strategic offensive actions - much different, for example, from the previous Anglo-French War, where the Bourbon fleet was used proactively to separate Britain from her colonies and chip away at their global positions. Naval battle in the Wars of the Revolution would have to wait until the French fleet had a compelling reason to come out of their ports.

This compelling reason, as it would turn out, was famine. The sprawling and intense land war across the entire eastern French periphery, combined with British control of the seas, had left the French once again thrown back on their internal resources all through 1793. Meanwhile, the mobilization of millions of young men had dovetailed with a poor harvest to create an increasingly dire food insecurity, which threatened to become an all out famine in 1794.

To rectify the growing food emergency, the government looked across the sea towards another young republic, and its envoys in the United States arranged for a large convoy of grain to be shipped to France - a voyage which would force it to run a gauntlet of British patrols, in a reversal of the more famous modern story of German submarines prowling for convoys bound for Britain. The grain convoy of 1794 would at last set the stage for a major naval engagement - the first of France’s revolutionary era.

In May, 1794, no less than four major naval bodies were sailing into the same vicinity of the Mid-Atlantic. The first of these was the massive French grain convoy, numbering some 130 merchant vessels loaded with foodstuffs, guarded by a handful of French warships. The second body was the French Brest fleet, comprising 25 powerful ships of the line, which was dispatched on May 16th under Admiral Villaret Joyeuse, with instructions to find and link up with the grain convoy in the mid-Atlantic and shepherd it home. Simultaneously, 26 ships of the British Channel Fleet under Admiral Richard Howe were prowling a wide patrol arc in the Bay of Biscay, searching for the same French convoy. To this already cluttered roster, we add a Dutch merchant convoy cruising through the channel en-route for Lisbon. All of these bodies would collide in the Mid-Atlantic by the end of the month.

Howe and his fleet suffered, as is often the case in war, by arriving at their destination too early. He had set sail on May 2nd, giving him a two week jump on the French fleet. He arrived at Brest in the 2nd week of May and reconnoitered the harbor - seeing that the French fleet was still anchored, he set out on a wide sweep of the Bay of Biscay in search of the French grain fleet, and returned to Brest on the 19th to check once again on the status of the French battle fleet. This time, however, he found the harbor empty: Villaret had slipped out on the 16th, leaving Howe in the lurch and forcing him to chase after the French, with dense fog masking their escape.

The ensuing chase had an element of excitement to it so extreme that it borders on farce. On May 19 - the exact day that Howe returned for a second peek at Brest and found that the French fleet was gone - that same French fleet was over a hundred miles west, sailing into the Atlantic, when it bumped directly into the Dutch merchant convoy heading for Lisbon. Villaret managed to snare and capture several Dutch vessels, which he crewed and dispatched back to France as prizes - but only two days later, as these captured Dutch ships were sailing back towards France, they ran into Howe’s fleet, which was in hot pursuit of the French armada. Howe therefore not only captured back the Dutch ships, freeing their crews, but also learned from them the heading of the French fleet.

The difficulty of navigating precisely in the open sea thus brought the two fleets into a circuitous sort of dance, with Villaret’s fleet weaving about in search of the French grain fleet, and Howe weaving in search of Villaret. It was not until the afternoon of May 29 that the fleets encountered each other far out at sea, at which point they spent two days maneuvering and fighting partial actions, with Howe seeking a decisive engagement and Villaret reacting defensively. The onset of pitched battle was delayed by intermittent fog, which roiled the area for nearly 36 hours.

On June 1, however, the fog cleared and clear sun shone down on two fleets of virtually identical strength (26 ships of the line each) tracking parallel to each other, with the French downwind. The ensuing battle is known simply as “The Glorious First of June” - named for its date because, rather uniquely, it was fought far out in the open sea, more than 400 miles from the closest land, and thus has no landmark to associate with it.

Villaret realized that, although he was running slightly ahead of the British fleet, he had not gained enough of a lead to avoid the battle (as he would have preferred to do), and accordingly shortened his canvas, meaning he reduced his sail to slow the speed of his line and free up crews for combat. Howe, observing that the French were slowing and preparing to fight, chose the opposite course of action and approached at full sail. His tactical intention was to launch an attack on the side of the French line - but rather than simply coming alongside the French and exchanging fire at close range, he intended for each of his ships to pass through the gaps in the French line, crossing to the downwind side and breaking the French formation apart.

Tactically, this was very clever - passing through the line, each British ship would be able to fire on two French ships, and having passed through they would now be downwind and able to cut off any French retreat. Howe evidently thought that this would be a clean wrap up of the battle in one blow, and he is said to have slammed his signal book shut with an “air of satisfaction.” Unfortunately, the order to slice through the French line individually was considered so unusual that much of the British line either misunderstood or ignored the order.

The lead British ship, the Ceasar, began the action by launching an attack on the lead French vessel, but rather than dashing down and cutting through the French line, the Ceasar simply formed up 500 yards from the French and began firing ineffective, long ranged broadsides. This greatly irritated Howe, particularly because he had previously contemplated replacing the Caesar’s captain (whom he considered incompetent), but had refrained at the request of the captain of his flagship, the Queen Charlotte. Upon seeing the Caesar botch the attack, Howe tapped the captain on the shoulder and said: “Look, Curtis, there goes your friend. Who is mistaken now?”

The Caesar, however, was not alone in misunderstanding and fumbling Howe’s order to drive into the French line. Of the 26 ships in the British fleet, only six - including Howe’s flagship, the Queen Charlotte - would drive through the line in the opening attack - the other five being the Marlborough, the Defence, the Brunswick, the Royal George, and the Glory. The remainder of the British fleet - with the exception of the poorly handled Ceasar - managed to draw at close range, though not passing through the French line, and the battle turned into a close quarters melee.

By mid-morning, the battle was already beginning to slacken. Seven French ships had been disabled, but Villaret managed to extract his flagship - the Montagne - and form a rallying point to the north, where he was joined by other captains breaking off from the engagement. By noon, Villaret had formed an improvised secondary battle line, with at least 11 ships in good condition to fight. As both fleets had suffered badly, Howe opted not to renew the battle and instead stood off to conduct repairs and secure the disabled French ships, which were taken as prizes.

Adjudicating the Glorious First of June is rather difficult. From the purest view of loss ratios, the battle was a British victory, with seven French ships lost against none of Howe’s. Despite all of his vessels still being afloat, however, Howe’s ships and crews had been badly battered, with several demasted vessels which required tows - as a result, he was unable to pursue or further press action with Villaret. Furthermore, despite defeating the French Battle Fleet, Howe was unable to intercept the French grain convoy, which made it safely home and prevented the French home front from succumbing to famine. Both Britain and France therefore celebrated the engagement as a victory, with London celebrating the captured French ships and Paris rejoicing in the safe arrival of the grain fleet. As Mahan would later put it, the French cruise had been “marked, indeed, by a great naval disaster, but had insured the principal object for which it was undertaken.”

On a tactical level, however, the First of June exposed a lassitude and indiscipline among the British captains, who largely failed to implement Howe’s orders correctly. The struggles of the French ships, with their uprooted gun crews and overpromoted officers, was to be expected, but the British - and Howe most of all - felt that they could have gotten more from the engagement. Still, France’s Brest Fleet was badly smashed, and would exert no influence in the war for some time. Instead, the center of gravity in the naval war would shift south, with the entry of Spain into the war as a French ally.

Enter, Nelson: The Battle of Cape Saint Vincent

The strategic reversal suffered by the British in the Mediterranean theater in the early years of the Revolutionary Wars was nearly totalizing in its scale. War began with the Spanish as a member of the anti-French coalition and a joint British-Spanish force capturing the French naval base at Toulon in lightning stroke with the aid of French royalists. Although Toulon was quickly besieged by the Revolutionary Army, under the command of one Napoleon Bonaparte, its occupation put the French Mediterranean fleet out of commission. With Spain in the allied camp, the Royal Navy now had the ability to operate virtually unimpeded in the Mediterranean.

Things began to go sour in December, 1793, when Napoleon recaptured Toulon after a bold operation to storm the fortifications overlooking the harbor. The British took pains to destroy as much of the French fleet and its stores as possible during their evacuation (most importantly, they managed to burn much of the timber in the dockyards), but fifteen French ships of the line survived the occupation of Toulon to form the nucleus of a Mediterranean battlefleet. Matters got further out of hand for the British in 1796, when Spain defected from the anti-French coalition. Spain’s war against France had gone badly, with French armies occupying Biblao in 1794. The Spanish court decided that, given Spain’s relative weakness, an alliance with her powerful French neighbor was the correct policy, regardless of the new revolutionary regime in Paris. Thus, in 1796 the Treaty of San Ildefonso was signed which brought Spain back into alliance with France, as it had been before the Revolution.

The sudden defection of Spain put the British in a precarious position. Spain had by this time sunk solidly into the second rank of the great powers, but her vast coastline made her an imposing presence on the prow of Europe, and the Spanish Fleet, in combination with the reconstituting French fleet at Toulon, was potentially much more powerful than the British Mediterranean Fleet, which was soon forced to abandon its bases in Corsica and Elba and withdraw to the safety of Gibraltar.

The overall balance of naval power then, was as follows. The British maintained undoubted naval supremacy on a global scale, particularly after battering the Brest Fleet on the Glorious First of June. In a strategic sense, the British maintained their ability to blockade much of the European coast and cut off Spain from her colonies. The Franco-Spanish coalition, however, maintained the ability to amass local supremacy in the Bay of Biscay and in the Western Mediterranean. The British Mediterranean Fleet disposed of just 15 ships of the line, while the Spanish Fleet and the French Toulon Fleet could amass up to 38 if they congregated together for action.

It is a point of particular interest, then, that the British fleet would be outnumbered and outgunned in the two decisive battles of the Mediterranean theater - these being the Battles of Cape St. Vincent and the Nile. In both instances, the British would defeat larger enemy fleets through a deadly nexus of superior seamanship and discipline, excellent gunnery, and brilliant tactical aggression on the part of one particular officer, who now bursts on the scene in full force. Nelson’s time had come.

The first opportunity for decisive action in the theater came in February of 1797. The Spanish intended to shuttle a large fleet - comprised of some 25 ships of the line - from the port at Cartagena, which lies in Spain’s inner Mediterranean coast, to Cadiz, which is on the Atlantic. Necessarily, then, the Spanish had to cross through Gibraltar in full view of the British fleet under Admiral John Jervis, which set out in pursuit with its 15 ships. The British chase was aided by a powerful easterly wind, which pushed the Spanish much further out to sea than intended, and created the space necessary to allow Jervis to close with them.

The Battle of Cape St. Vincent began in the most cinematic and suspensful manner possible, with the two fleets drawing near in dense fog. Jervis knew that the Spanish fleet had been driven out to sea in a loop and would be working their way back towards the coast, but did not have an exact pin on their location or disposition. On February 11, a British frigate managed to sail right past the Spanish in a thick early morning fog bank and delivered a report to Jervis, allowing him to dial in his search. By the morning of the 14th, the fleets were within some 30 miles of each other, and the British could hear Spanish signal guns firing in the distant fog.

As the mist cleared in the sunlight on the 14th, Jervis at last could see the Spanish at a distance. The British fleet - comprised of just 15 ships of the line - was decisively outnumbered by the Spanish, who counted 25 line ships, but Jervis could immediately see a tactical opportunity. The Spanish admiral, Jose de Cordoba, had neglected to order his fleet and keep them on station - rather than sailing in an orderly battle line, the Spanish ships were clustered in a pair of masses, with 16 ships in the forward cloud, 9 in the rear, and a distance of several miles between the two bodies. With the Spanish fleet both divided into two masses and unprepared for battle, Jervis saw that he had an opportunity to engage a larger enemy fleet on favorable terms - and even more importantly, defeat the Spanish before they could link up with the French fleet. Jervis immediately ran up signals to prepare for battle, commenting stoically to the officers on his flagship, the Victory, that “A victory to England is very essential at this moment.”

The signals from Jervis’s flagship offer an insightful look at the brevity and decisiveness that characterized good command and control in this era. The essence of Jervis’s entire battle plan was communicated to the fleet with just three signals, delivered at the following times:

11:00 AM: “Form in a line of battle ahead and astern of Victory as most convenient.”

11:12 AM: “Engage the enemy.”

11:30 AM: “Admiral intends to pass through enemy lines.”

With just these three signals, the British fleet wheeled into action with deadly purpose. They had originally been approaching the Spanish in two parallel columns, but at the first signal the two columns began to merge into a single consolidated battle line, which plowed straight into the gap between the two Spanish masses. Jervis’s intention was to split the gap and deliver scathing fire on the rear Spanish division, repelling it and forcing it to turn away, so that he could wheel his own line in pursuit of the lead Spanish ships.

The opening pass of the battle went well for the British line. Sailing in a tight column, they passed directly between the separated clouds of Spanish ships. The rearmost Spanish division, seeing that the British were going to cut them off from their comrades, attempted to drive through the British line, but the withering fire of the passing British ships tore up the lead Spanish vessels and forced them to turn aside. The first Spanish ship to approach, the Principe de Asturias, received two broadsides, including one from Jervis’s Victory, and was forced to break away from the battle.

Jervis now had his line squarely between the two Spanish groupings. The rear Spanish squadron had been smacked in the nose and was turning away from the fight, giving the British an opportunity to wheel and engage the Spanish vanguard. Unfortunately, the lead Spanish division had wasted no time peeling into the wind - not to fight, but to sail away from the battle and make for Cadiz. Jervis had already begun to wheel his line about in pursuit, but with the wind blowing to the northeast the Spanish had already begun to pull away. This threatened a disaster for the British. The entire point of this engagement was the unique opportunity for an outnumbered British fleet to engage the enemy while they were divided and in disarray - if the Spanish managed to simply haul off into the wind and escape, the day would be wasted in its entirety.

Jervis had his line turning into the wake of the Spanish to pursue, but they seemed to be too late. The prey was escaping. The lead British ship, the Culloden, was within range of the rearmost Spanish vessels, but most of the Spanish fleet was on track to slip away.

At this juncture, however, a lone British warship suddenly hauled out of the line. This was the HMS Captain, under the command of Commodore Horatio Nelson. Nelson - situated third from the rear of the British line - could see what was happening in its entirety. The Spanish were now passing him on the opposite course, and he could see that the Culloden and the front of the British line were coming about too slowly to catch them. Seeing that the enemy was escaping, he chose the course of maximum aggression and wheeled out of the line alone, executing a sharp turn and driving between the two friendly ships behind him, heading at top speed straight for the Spanish mass all alone.

Nelson’s independent decision to break formation and attack the Spanish mass instantly changed the trajectory of the battle. Nelson’s Captain was a modest 74 gun ship, charging straight into a cloud of sixteen Spanish vessels, several of which counted over 100 guns. His attack had an aura of suicidal recklessness to it, but it achieved a fantastic shock value. The Spanish, evidently thinking that they were going to sail clear of the battle, were taken aback by the spectacle of a lone British warship bearing down on them, and several Spanish ships collided as they tried to steer away from Nelson. The shock of Nelson’s attack recalls the words of American novelist Charles Portis in his western classic True Grit:

You go for a man hard and fast enough and he don't have time to think about how many is with him, he thinks about himself and how he may get clear out of the wrath that is about to set down on him.

This was precisely what occurred in the Spanish fleet. The Captain, as it crashed into the Spanish mass, came under fire by no less than six enemy ships, but the shock value of Nelson’s charge completely disordered the Spanish fleet and allowed the rest of the British line to spill into the action. Jervis, seeing and understanding what Nelson was doing, immediately signaled for the rear of his line to support the Captain - and not a moment too soon.

Nelson’s ship suffered tremendously battling in the center of the Spanish fleet alone. By mid-afternoon the Captain had been de-masted and had her wheel shot away, making her entirely unmanageable. Remarkably, this did not diminish Nelson’s aggression at all - he grappled his drifting ship with the Spanish San Nicolás, which had collided with the San José in their efforts to avoid his charge. He ordered his men to board and capture the San Nicolas, then cross over to the San Jose and board her too, with Nelson receiving the swords of both their captains in surrender.

The Battle of Cape St. Vincent was a deadly display of British tactical prowess which cast the relative proficiency of the fleets into sharp relief. The Spanish fleet was undoubtedly stronger in ships (25 against 15), total cannon (with well over 2,000 combined guns against some 1200 British guns), and manpower. The Spanish, however, never ordered themselves for a fight and were caught flat-footed in an attempt to escape action, while Jervis’s smaller force sorted itself out efficiently for action and proved highly aggressive in the attack. In contrast to Jervis’s single-minded drive for action, the Spanish admiral, Jose de Cordoba, never exerted meaningful command over the battle.

If the British advantages were primarily discipline, decisiveness, and tactical aggression, Commodore Nelson was the veritable avatar of all these things. He changed the battle in an instant at around 1 PM, observing that the Spanish were beginning to slip away and instantly choosing to wheel his own ship out of the line to attack. This unexpected rupture in the British line, with Nelson charging into the Spanish flank, was the singular moment that prevented the battle from ending indecisively: the subsequent disordering of the Spanish led to the capture of four Ships of the Line and inflicted some 4,000 Spanish casualties, against a mere 300 dead and severely wounded among the British.

Nelson’s turn at Cape St. Vincent served as an iconic moment of foreshadowing for the great exploits that he would soon become known for. He was an officer with an instinctive aptitude for aggression and initiative, willing to take risks that bordered on suicidal recklessness. It is difficult to exaggerate just how reckless this maneuver was. His charge at the Spanish flank obviously entailed tremendous physical danger to both Nelson and his crew, with the Captain sailing into a maelstrom of fire with at least six Spanish ships - and indeed, the Captain was horrifically damaged by the end of the day. But Nelson’s charge also entailed a professional risk, in that he disregarded Jervis’s orders that the fleet hold a battle line - later, Nelson’s actions were justified as an interpretation of a vague instruction from Jervis to “take suitable actions to engage the enemy.”

In short, Nelson faced the imminent possibility of mutilation, professional disgrace, court martial, and death when he broke out of the line, but all of these concerns were overridden by his instinctive desire to grab the enemy and bash him. This attitude can be compared very favorably to the culture of the classical Prussian officer corps, which had a strong tolerance for the independence of field commanders in the attack. Prussian officers understood that they were extremely unlikely to be punished for disregarding or playing fast and loose with orders when they had the opportunity to attack. Nelson embodied a similar ethos at sea - one that skillful superiors like Jervis welcomed and empowered. After the battle, with his uniform torn and blacked from action, Nelson was received on Jervis’s flagship to profuse praise. Nelson remembered: “The Admiral embraced me, said he could not sufficiently thank me, and used every kind expression which could not fail to make me happy.”

When the news of the victory at Cape St. Vincent reached Britain, it caused a surge of energy and patriotism, with the public latching on to Jervis and Nelson in particular as heroic figures who had reinvigorated confidence in the British fighting man. For most in Britain, this was the first they had heard of Nelson’s name - but it would by no means be the last. The career of this emerging British hero was on the verge of dovetailing with the military supernova rising on the continent. Napoleon was going to sea.

Nelson’s Masterpiece: The Battle of the Nile

After the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, naval action in the Mediterranean languished for a year. The battered Spanish fleet took refuge in its base at Cadiz, and the victorious British began a watchful blockade, keeping the Spanish ships bottled up where they could not threaten Portugal (a key British ally). For the remainder of 1797, Nelson’s lone meaningful action would be a botched amphibious assault on the Spanish Canary Islands, which resulted in the deaths of hundreds of British marines. Nelson himself took a musket ball to the right elbow which shattered the bone. The limb was hastily amputated at the elbow, and Nelson was forced to recuperate in England for several months. Now 39 years old, his missing limb and partial blindness were a testament to his extreme tactical aggression and personal bravery.

The Mediterranean swung back into full force as a theater of action in 1798, under the auspices and initiative of Napoleon, who like Nelson had become the rising military superstar of his country thanks to his performance in the opening rounds of the war. The Directory in Paris had declared war (again) on Britain, and were seeking the opportunity to wage a proactive campaign against global British power. With the prospect of a cross channel invasion bleak given the superiority of the Royal Navy, it was Napoleon who suggested an expedition to Egypt in a speculative attempt to strike at the British underbelly. The Egyptian enterprise carried a variety of tenuous and loosely connected objectives, ranging from a poorly defined scheme to improve French trade linkages in the middle east, all the way to Napoleon’s more ambitious proposal to threaten British India.

Whatever its ultimate guiding animus, in the spring of 1798 the French naval base at Toulon became a beehive of activity as Napoleon assembled his invasion force - 40,000 men, requiring nearly 300 transports to carry them with their horses, cannon, and supplies. The ground force was to be escorted by the Toulon battle fleet, consisting of 13 ships of the line, including the massive 124 gun l’Orient, under the command of Admiral François-Paul Brueys d'Aigalliers. In order to conceal their intentions from the British, absolute secrecy was maintained, such that only Napoleon and his immediate subordinates even knew what the objective of the expedition was.

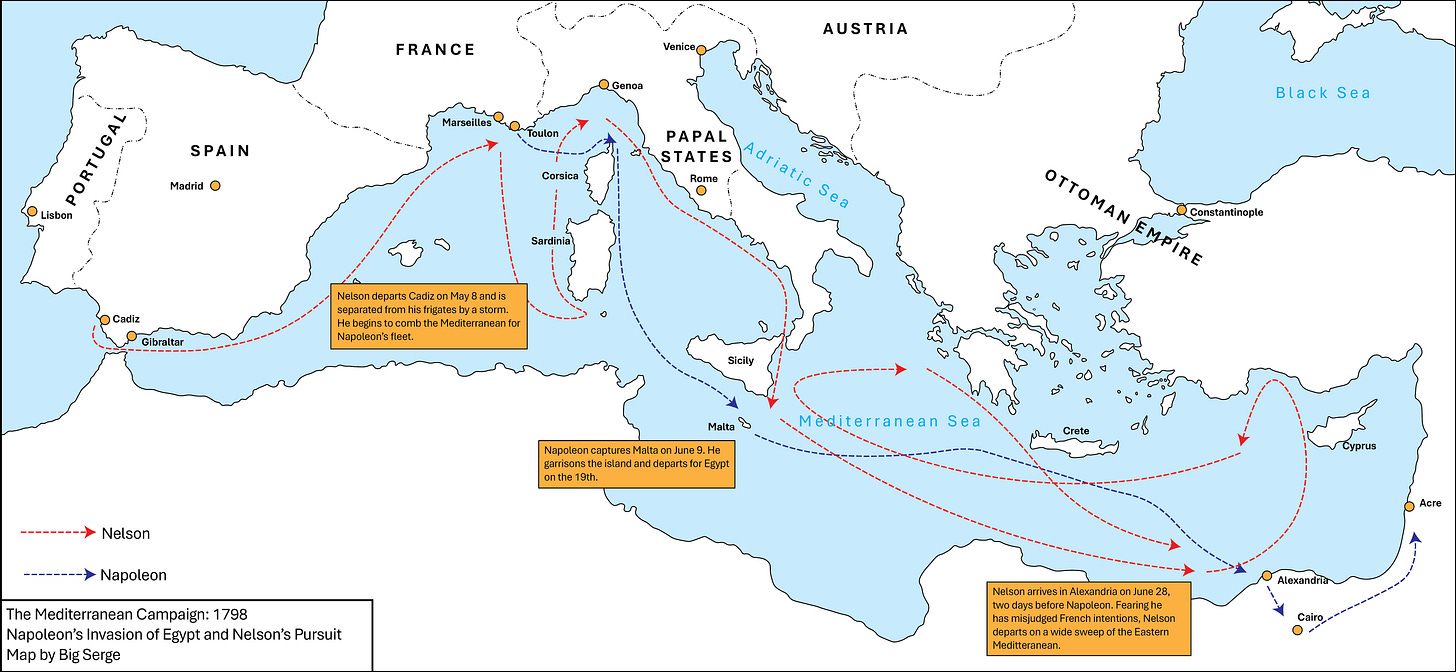

Despite French OPSEC, it was impossible to conceal the buildup at Toulon entirely, and by late May the Royal Navy was well aware that a large force was preparing to depart - though for what destination, they did not know. Admiral Jervis, commanding the watchful blockade of the Spanish fleet at Cadiz, was ordered to dispatch a squadron to reconnoiter Toulon and keep tabs on the massing French fleet. He had the perfect man for the job in Nelson. Thus, the stage was set for a dramatic chase across thousands of miles, worthy of any Hollywood blockbuster.

On May 8, Nelson passed through the strait of Gibraltar in his flagship, the 74 gun HMS Vanguard, along with the Orion and the Alexander (also 74s) and three frigates. The date is rather serendipitous, because it was the next day (the 9th) that Napoleon arrived in Toulon from Paris and began the process of embarking his army for departure. On May 19, the French fleet began to spill out of Toulon with its massive cloud of transport craft. The following day, Nelson’s little squadron ran afoul of a terrific storm, which was to have profound implications. The storm not only completely demasted the Vanguard, forcing Nelson to anchor at Sardinia for repairs, but it also scattered his three frigates.

The captains of Nelson’s frigates presumed that, with the little fleet scattered by the storm, Nelson would return to the British base at Gibraltar to regroup - naturally, therefore, that is where they headed. Nelson, however, had his blood up to hunt the French fleet and was in no mood to return to base - especially because a little brig arrived off the coast of Sardinia and informed him that Jervis was sending him 11 additional ships of the line. Jervis, however, naturally had no clue that Nelson had lost his frigates in the storm, and accordingly did not send him any.

Nelson’s loss of the frigates on May 20 was to have a profound effect on the ensuing chase. Frigates were smaller, lither, and more lightly armed vessels (usually with something on the order of 34 to 40 guns). Much too small to tangle in close quarters with the huge line ships, frigates instead filled extremely important roles as scouts, messengers, and recovery vessels, sailing ahead of the main fleet, peeking into harbors, and carrying dispatches. A fleet comprised entirely of heavy line ships was, without putting too fine a point on it, blind, and the storm of May 20th had firmly blinded Nelson precisely as the French were departing from Toulon.

Bereft of his frigates, Nelson stayed true to form and took the maximally aggressive and decisive course of action. His orders were to find the French fleet and sink it, so that is what he did - frigates or no frigates. On June 7, a row of masts crested the horizon from Nelson’s vantage point off Sardinia. These were the 11 ships dispatched by Jervis to be his reinforcements, bringing Nelson’s total strength up to 14 line ships - all of them 74 guns, with the lone exception of the 50 gun Leander. It was time to hunt.

Nelson set out again on June 10, working his way around Corsica and down the coast of Italy in search of the French. By this point, however, he was already well behind. Napoleon and Admiral Brueys had arrived at Malta (then under the control of the Knights Hospitaller) on June 9 and had captured the island, spending over a week there establishing a French occupation and deprovisioning their ships.

Napoleon’s relatively long stayover in Malta gave Nelson an opportunity to close the gap, and it created a close call which ably demonstrates the role of chance and uncertainty in warfare. Napoleon did not leave Malta until June 18, at which point Nelson was already close by, off the coast of Sicily. However, on June 22 Nelson stopped a small merchant vessel, whose captain told him that the French had departed Malta on the 16th. Operating with this incorrect information, Nelson believed that the French had a head start of nearly a week, and guessed (correctly) that Napoleon’s objective was Egypt.

Believing that the French had a much longer head start than they actually did, Nelson decided to set off for Egypt at top speed - a choice which caused him to miss an opportunity to catch the French on the open sea. On June 22, the Leander actually faintly spotted several of Napoleon’s ships on the horizon, but Nelson (thinking the French were already hundreds of miles ahead) decided to ignore the sighting and go straight to Egypt. Again, the lack of frigates severely impeded his ability to search thoroughly.

Racing at top speed for Egypt, Nelson’s fleet rapidly outpaced the French (who were slowed by the lethargic troop transports), and by midday on June 23, the British had passed Napoleon’s fleet. Still operating under false intelligence, Nelson believed the French were ahead, when in fact it was now he that was leading. On June 28, Nelson’s fleet sailed into the harbor at Alexandria and found it empty of French warships. This appears to have shocked Nelson, as he had calculated that the French fleet ought to have arrived there the day before. Finding the port empty, Nelson immediately hauled his fleet off to the east and began a sweeping search of the Eastern Mediterranean, combing the Levantine coast, the inlets of southern Turkey, and the coasts of Crete and Greece, before sweeping all the way back to Sicily.

Nelson was a man of action and decision. When he found the giant harbor at Alexandria devoid of French ships on June 28, he immediately supposed that he had incorrectly guessed Napoleon’s destination and departed to resume the search. In fact, if he had loitered at Alexandria for just a day, he would have been waiting when the French fleet pulled into view. By the 1st of July, Napoleon’s army was ashore in Egypt, and the French ships of the line had anchored in Abu Qir Bay, some 12 miles northeast of the city - but by this point, Nelson was already moving at high speed up the coastline towards the Levant.

Nelson came tantalizingly close to intercepting the French on the open water on multiple occasions, in scrapes so close that it is difficult to believe they really happened - particularly given the vastness of the Mediterranean. The distance from Gibraltar to Alexandria is some 2,000 miles as the crow flies, but Nelson’s route was much longer, with its circuitous path along the coast of France and Italy, searching every inlet and harbor for the enemy fleet. In all, Nelson’s fleet traveled well in excess of 5,000 miles in its search, and yet on multiple occasions they came frighteningly close to finding the enemy. Nelson was within 70 miles when the storm of May 20 scattered his frigates, and on June 22 he came as close as 30 miles - later that night, as he passed the French in the dark, they were so close that French sailors could hear the sound of British cannon signaling each other. Later, he arrived at Alexandria only a day ahead of Napoleon. Near miss after near miss, much to Nelson’s frustration.

Nelson could apprehend on multiple occasions that he was on the right trail, and that his own instincts had caught Napoleon’s scent. This is why the lack of frigates weighed so heavily on him, and in hindsight (knowing, as we do, how close the fleets came to each other) we can rightly say that Nelson probably would have caught the French between Malta and Alexandria if he had only had a few frigates to widen his search radius. He would write in his diary during the chase: “Were I to die at this moment, ‘want of frigates!’ would be stamped on my heart.”

Equally important, however, was the incorrect intelligence that he received off the coast of Sicily, when he was told that the French had left Malta on June 16 (when in fact Napoleon had not departed until the 18th). Nelson seems to have grabbed on to this report as his one solid piece of intelligence and based his calculation of the French position off of it, but of course it was wrong, and so he misjudged his arrival at Alexandria.

The upshot of all this chasing was that, rather than catching the French in the open water in early June (when the French warships would have had the difficult task of trying to defend the vast cloud of transport ships), Nelson spent not only the remainder of June but also almost the entirety of July searching the Mediterranean in vain. On July 25 - the day that Napoleon smashed the Egyptian Mamluks at the Battle of the Pyramids - Nelson’s fleet was a thousand miles away off the coast of Sicily. It was not until the HMS Culloden, in a stroke of random fortune, encountered and captured a French merchantman carrying wine that Nelson learned the truth, that Napoleon had arrived in Alexandria only a day after his own visit to the port. This news, which confirmed Nelson’s suspicion that Egypt had been the French objective all along, seems to have energized the admiral, and he hauled off for Alexandria at top speed.

Nelson’s fleet arrived at Alexandria on August 1 to find the French tricolor waving over the city and the port clogged with French transports and merchant vessels. Curiously, however, none of the French ships of the line were to be seen. After their June arrival, Admiral Brueys had considered a variety of options as to where and how to station his warships, and had chosen to deploy them in Abu Qir Bay - a gently curved, semi protected stretch of coast just to the east of Alexandria. That is precisely where Nelson found them on the evening of June 1.

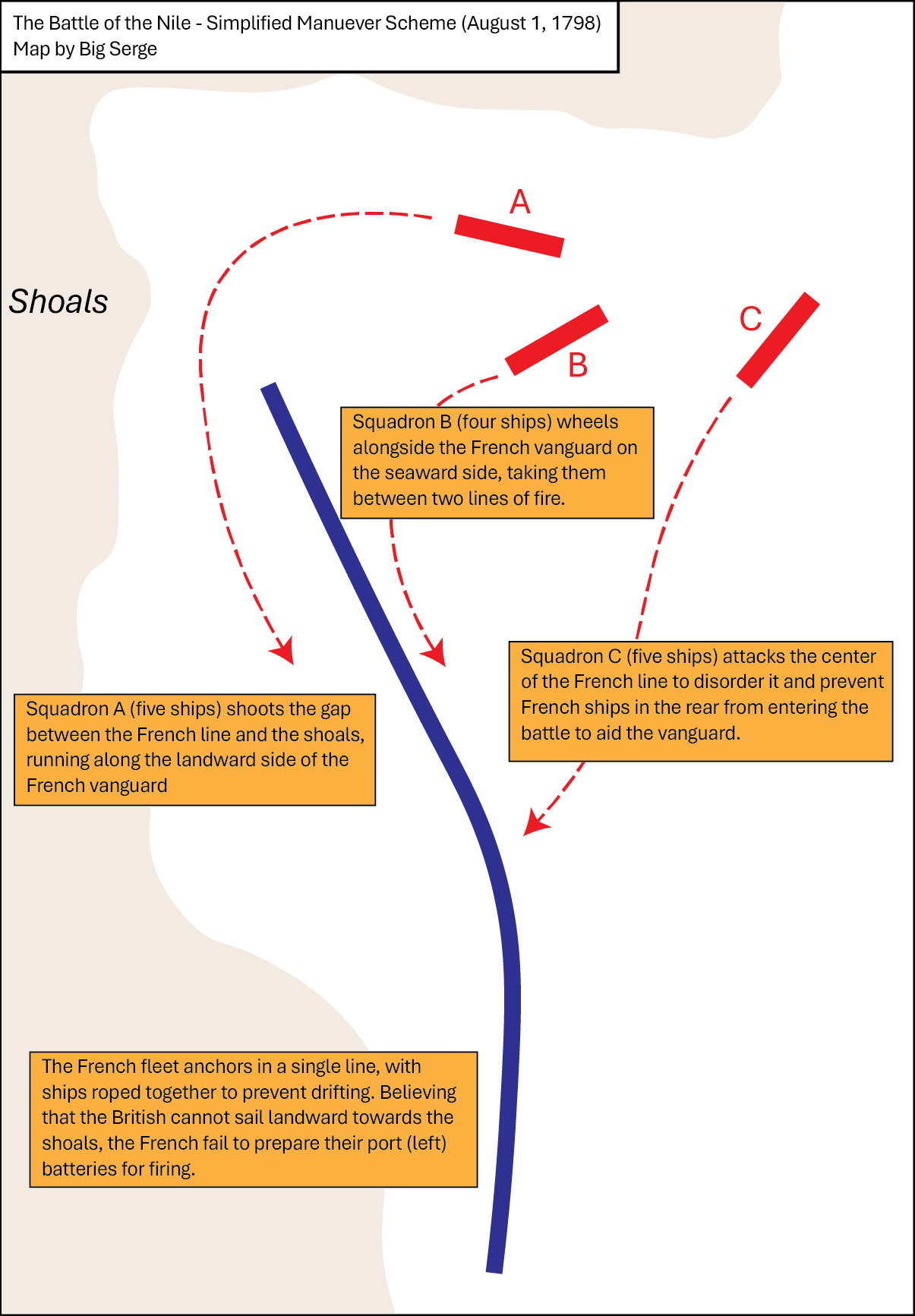

Brueys’ chief concern, from the beginning, had been the possibility that Nelson might come upon his fleet in anchorage, and the French deployment was chosen specifically to give them the best odds (as Brueys saw it) in the event of a battle. The French warships, comprising 13 ships of the line, were anchored in a gently curving battle line across the width of Abu Qir Bay, protected (or so they hoped) by the shoals. Brueys believed that by forming his line snugly against the curvature of the coast, he would leave the British unable to maneuver around him and compel them to take the fight straight up against the seaward flank of his line. To ensure the integrity of the line, Brueys had taken the additional step of lashing many of his ships together end to end with heavy cables, to prevent British ships from breaking through.

The overall tactical schema from the French, then was very simply to transform their line into an immobile, anchored fortress, protected by the coastline. It is clear that they considered it an impossibility that the British would be able to squeeze between their line and the coast, as evidenced by the fact that the port French batteries (that is, the cannon facing the shore) were not prepared for action. If the battle had proceeded as Brueys envisioned - that is, as a straightforward exchange of fire between lines - the French had reasonable prospects of success. Both fleets had 13 first rate ships of the line, but whereas all of Nelson’s ships were 74s, Brueys had a pair of heavier 80s as well as the mammoth l’Orient, with her 120 guns.

Several factors, however, would ruin the French vision for the battle. In the first place, the entire positioning of the French fleet had been botched. Brueys was counting on the shoreline to keep the British from getting behind his line, but the French ship at the front of the line - the Guerrier - was anchored nearly 1,000 yards from the edge of the shoals, leaving a gap that was small (in naval terms) but still adequate for British warships to slip in. Secondly, the French had neglected to anchor the sterns of their vessels (that is, they were anchored only at the bow) which allowed them to swing somewhat freely in the wind, creating further gaps in the line where British ships could penetrate. Finally, Brueys severely underestimated the tactical aggression of Nelson and his captains, who arrived on August 1 ready to give battle immediately.

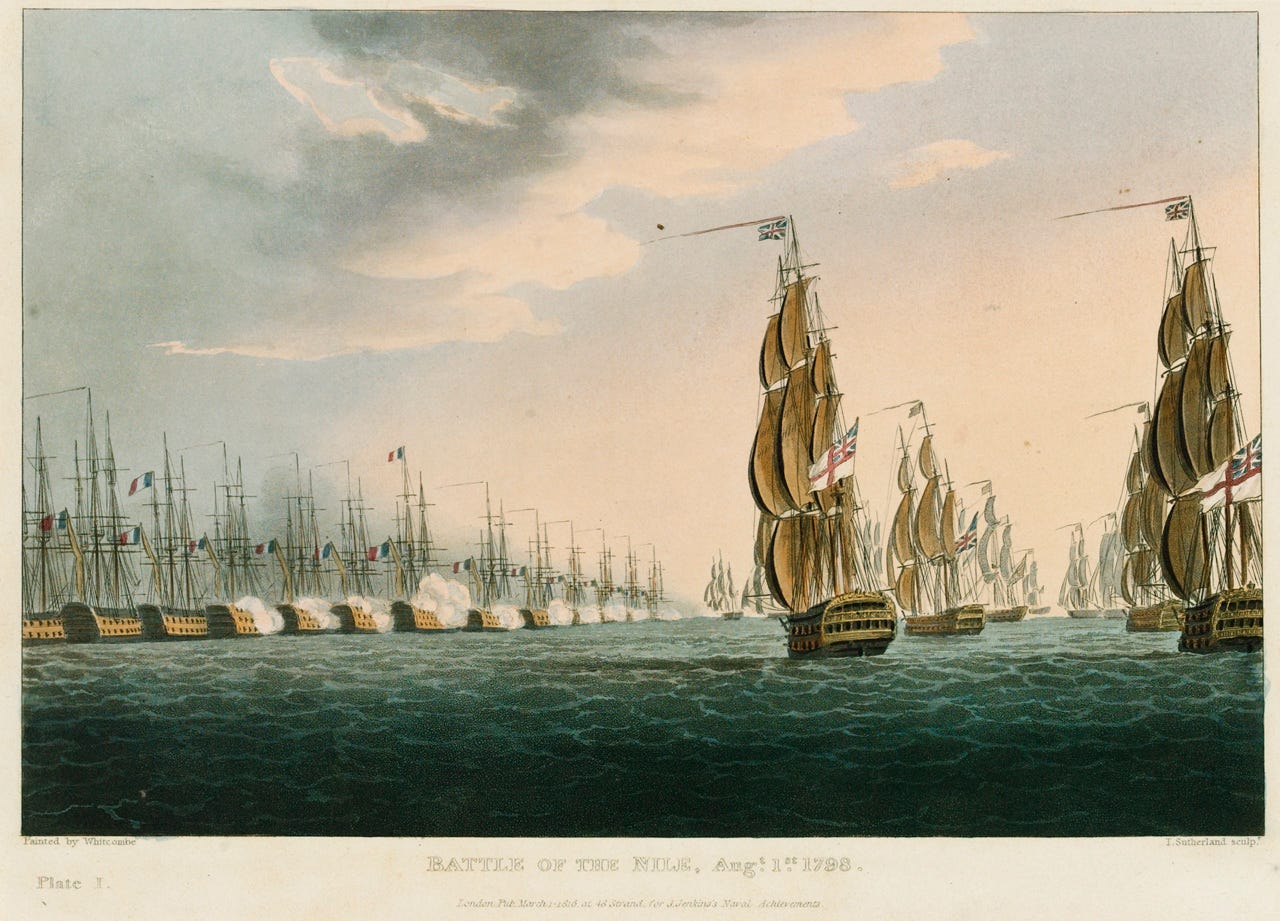

The great battle in Abu Qir Bay, which comes down to us in history as the Battle of the Nile, was a singular demonstration of Nelson’s aggression, tactical flexibility, and penchant for decisive action. The French had been in their anchorage for over a month, while Nelson’s fleet had only just arrived after weeks at sea. Nevertheless, Nelson was determined to take the fight immediately and drew up to attack. The critical action would be fought overnight from August 1-2, with the first shots fired in the early evening, just a few hours after the British arrived at Alexandria.

Nelson’s plan of action centered on the crucial fact that the French battle line was anchored, and thus immobile. The initial schema aimed to take advantage of French immobility to attack the vanguard and center of the line, attacking each French ship with two British vessels, and creating a local superiority at the front while the French rear sat idly at anchor. As the lead British vessels rounded into the bay, however, they noticed an unexpected gap between the Guerrier and the shore. Captain Thomas Foley, on board the Goliath at front of the British attack, decided independently to veer into the gap between the French and the shore.

It is difficult to understand how disorienting the beginning of the battle was for the French. The British fleet first came into sight at about 4 PM on August 1 - Brueys recalled those of his men that were on shore and weighed his options, but judged that it was late in the day and the British were unlikely to seek a night battle so soon after arriving. Simultaneously, however, Nelson was dining with his officers and expressing his determination to give battle immediately, famously saying: “Before this time tomorrow I shall have gained a peerage or Westminster Abbey.” At 5:30 PM, Nelson signaled for his lead ships - the Goliath and the Zealous - to lead the attack into the harbor. By 6:20 PM, the the fleets were exchanging fire and the battle had begun. Finally, at 6:30 PM the Goliath crossed over the head of the Guerrier and slipped between the French line and the shore.

This was an incredible and sudden turn of affairs. Less than three hours after the British first arrived in the area, the battle had not only begun, but British ships had penetrated between the French line and the shore - a disaster that Brueys had thought an impossibility due to the shoals. The speed and urgency with which Nelson sorted himself out for battle and the ferocious tactical aggression of the British put the French permanently on the back foot, and they spent the subsequent hours in a state of total reactivity.

The British fleet attacked in three subsequent columns, comprised of five, four, and four ships respectively. The first column, led by the Goliath, dashed into the gap between the Gurrier and the shore and began to work its way up the French line on the shoreward side. The British attacked in a leapfrogging style, firing broadsides as they went before each British ship dropped its anchor to settle directly alongside a French counterpart. What this meant was that, within the first hour of the battle, each of four French ships at the front of the line now faced a British ship anchored directly alongside it on the shoreward flank. This was a disaster for the French, as they had not prepared their shoreward batteries for action, and the lead French vessels suffered terribly in the opening salvos.

One British ship, the Orion, was surprised as it worked its way along the shore to come under fire by the French frigate Serieuse. It was considered a standard nicety of battle at the time that lightly armed frigates did not exchange fire with line ships. Frigates were too small to exert a meaningful influence in a pitched battle - their main role was recovering overboard sailors and towing away damaged ships - and it was considered a gentlemanly protocol to leave them alone in battle. The 36 gun Serieuse’s ill-advised decision to shoot at the 74 gun Orion evidently greatly irritated Captain James Saumarez, and he paused to unleash a point blank broadside which reduced the little French ship to a wreck. The Orion then continued its attack run along the shoreward flank of the main French battle line.

After the first British attack run, then, the French were already in disarray - caught completely off guard by the British run into their shoreward side, scrambling to open their left hand batteries to return fire. It was at this moment, as the French were in a state of extreme disorientation, that Nelson led the attack of the second British column, which now ran up along the seaward side of the French just before 7:00 PM, taking several most of the French vanguard in a deadly crossfire.

As night fell on the Egyptian coastline, Abu Qir Bay remained lit by the blazing signal lamps of the British fleet and the fires that now raged on the decks of the French. The burning fires, shrouded by smoke beneath a darkening sky, gave the battle a stygian and cinematic quality, but a peek through the smoke would have revealed the French fleet steadily wasting away under the deadly British crossfire. By 10:00, most of the French vanguard was disabled to various extents, and surviving French captains began to surrender.

The battle was not without blemishes for the British fleet. One of Nelson’s rearmost ships, the Culloden, was grounded while attempting to round the shoals and spent most of the battle attempting to free itself unsuccessfully with the aid of the little cutter Mutine. The grounding of the Culloden was a poignant reminder of just how small the margin of error was for the British attack as it skirted the shoals. Meanwhile, HMS Bellerophon, attacking the French center, misdjudged its approach and accidentally found itself tangling with Brueys’ powerful flagship - the 120 gun l’Orient. By 8 PM, the massive firepower of l’Orient had collapsed all three of the Bellerophon’s masts, and her captain was forced to cut his anchors and allow the shift to drift away from the battle.

l’Orient, however, had suffered badly as well, and by 9:00 the British observed a fire raging on the lower decks of the French flagship. French fire control was now failing, owing to the destruction of the deck pumps by British shot, and Captain Benjamin Hallowell of the Swiftsure ordered his gun crews to begin firing directly at the burning decks of l’Orient, which spread the flames and prevented the French from fighting the fire. Finally, at 10 PM, the fire reached the powder magazine, and l’Orient exploded in a colossal fireball, which temporarily stopped all the fighting as ships British and French alike scrambled to get clear of the blast. Admiral Brueys had already been killed by this point (nearly cut in half by a direct hit from a cannonball), and now the burning hulk of his flagship carried him down in an improvised burial at sea.

The detonation of l’Orient marked the climax of the battle which put the finishing touch on the French discombobulation, with their exploded flagship blowing a literal hole in the center of their line. Several ships in the French rear (which had not been engaged up to this point) cut their anchors to get away from the fires, and inadvertently drifted backwards into the shoals. Two French ships, the Heureux and Mercure, were captured almost completely intact when the morning light revealed them stranded on the shoals at the southern end of the bay, while another -the Timoleon - was destroyed when it ran aground in a botched attempt to escape, and was then set alight by her crew to prevent her capture. And that, as they say, was that.

The Battle of the Nile was a quintessentially decisive battle. In a single night, Nelson smashed the entire French Mediterranean battle fleet in a victory so comprehensive that it bordered on annihilation. Of the 13 French ships of the line that participated, 11 were lost, along with two of the four French frigates on scene. The price for destroying virtually the entire enemy fleet was just three disabled ships, all of which were recoverable: the grounded Culloden, and the Bellerophon and Majestic, both of which were demasted in duels with larger enemy ships. It is not an exaggeration to call the Nile the single most decisive victory in the age of sail: the entire enemy battle fleet annihilated in a few hours, winning near total control over the Mediterranean in one moment.

What stands out most about the Nile was the extreme tactical aggression displayed by Nelson, and the high tempo of his attack. The battle reached its crescendo with the explosion of l’Orient at roughly 10 PM: just six hours after Nelson’s fleet arrived near Abu Qir Bay. In a single night, Nelson strategically checkmated the entire French expedition to Egypt: bereft of the fleet, Napoleon’s army was now stranded far from home, and he was soon forced to abandon his army and evacuate back to France.

The Nile bore all the hallmarks of Nelson’s personality and genius, particularly his aggression and personal bravery. Abu Qir Bay was not a well charted zone for the British, and in fact they lacked depth charts or a clear view of where the shoals were. Brueys was confident that a night attack skirting the shoal would have been suicidal - and indeed, the grounding of the Culloden shows that the British were taking a serious risk by making an attack run so close to the shallows. Nelson, however, judged that tempo and aggression were more important than exhaustive prudence. Brueys believed that he had all night to prepare for battle, but in reality he had approximately 45 minutes.

It may be worth considering, for a moment, the particular role that Nelson played in winning the battle. It is true that he did not micromanage the actions of his ships of course, and that such finely tuned command and control was not possible. Nor was he the architect of British gunnery or the designer of her ships. Nevertheless, a great deal of credit belongs personally to him, in that his command instilled a spirit of aggression and risk taking in his captains, and his sketch of the battle plan created the rapid attacking tempo that unhinged the French.

In the many weeks that they were at sea, combing the Mediterranean for the French fleet, Nelson held frequent conferences with his officers, at which they sketched out various plans of action and contingencies, depending on the disposition of the French fleet. Nelson had his captains prepared for action well in advance and preached an aggressive ethos in battle, and this fact explains why the British were able to offer battle with a coherent maneuver scheme almost immediately after arriving. Furthermore, Nelson encouraged risk taking by his readiness to shower effusive praise on subordinates when they acted decisively, and set a personal example by exposing himself without reservation to danger. At the Nile, he was wounded by a piece of shrapnel which shredded his forehead. The bleeding was so severe that he told the surgeon: “I am killed. Remember me to my wife.” But of course he was not killed, and returned to the deck for action as soon as he had been stitched up, later refusing to enter his name in the casualty list.

Both by his personal example and through his calls for an aggressive attacking tempo, Nelson created a schema of tactical aggression that was understood by all of his captains. He bears a close resemblance to land generals par excellence like Napoleon and Von Moltke, who not only showed deft operational touch but also produced a culture of aggression, tempo, and an instinctive desire to get at the enemy and attack him immediately. At the Nile, Brueys and his fleet ended up disordered, disoriented, and cognitively overwhelmed by Nelson’s initiative, and the British achieved the ultimate dream of naval combat: seizing command of an entire sea in a single night through the annihilation of the enemy fleet.

Nelson Unblocks the Baltic

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.