The American Experience in World War Two is a rather delicate subject to touch, for a variety of fairly obvious reasons. The American war effort is regarded with absolute moral certainty, and victory was achieved with what seems - at a distance of 80 years - to be almost trivial ease. The American homeland was completely unmarred by the war, with American society, finances, and industry emerging from the war not only intact but in many ways significantly stronger. Unlike Britain, which was victorious but increasingly shaken and aware that it had been eclipsed, or the Soviet Union which bore catastrophic scarring and the haunting memory of tens of millions of dead, America’s war experience imparted unmatched confidence and a sense of reassured power. The story here was fairly simple, at least for the American social imaginary - with the world on the brink of domination by a pair of despotic and totalitarian powers, personified in the fight by the Wehrmacht and the Imperial Japanese Navy, America rose from her idle slumber and put things right, sweeping both of them from the board in a few years with relative ease.

For Americans then, world historic importance hinges on Normandy. The D-Day Landings of June 1944 tend to be the most widely held impression of America’s war - a climactic moment in a military historiography that is extremely linear. This linearity is rather interesting. Britain and the USSR, for example, experienced years of defeat as they endured the early German onslaught, and they reached their respective moments of low ebb - Britain in 1940 as it frantically evacuated the continent, and the USSR in 1941 with the panzers barreling towards Moscow. For America, there was no widely recognized low point to speak of - only forward churn. Americans never felt that it was possible for them to lose the war. There were no steps back, only forward, and no real anticipation of losing ground. The suggestion that other parties had borne the brunt of the fighting - for example, that 80% of German losses occurred at the hands of the Red Army - were casually dismissed with a hand wavy reference to Lend Lease. No wonder, then, that American postwar confidence was so high.

In the grand strategic sense, this is no doubt true. America emerged from the war as the absolutely preeminent naval, aerial, industrial, and technological power in the world, and would in time build up this lead to become the single most powerful nation that the world has ever seen. At no point was American strategic defeat a real possibility. On the operational and tactical levels, however, America’s war was not so easy. In fact, the American military entered the war in a state of doctrinal uncertainty and had to learn on the fly how to fight a continental scaled ground war of the sort the Germans, French, and Russians had been fighting for generations.

That is what we will discuss today. It is one thing to say that the enormous power of America made its eventual strategic victory inevitable. But for the individual GI on the ground, what was the comfort there? For a young man from Missouri, dropped into the desert to face a veteran Panzer force which had been practicing its craft for years, how much consolation was it to think about factors like GDP or the output potential of the Detroit automotive complexes? He was far more concerned with practical matters, like how to hold his position against a Panzer attack, or how to assault a strongly held German gun nest. Converting America’s astonishing latent power into fighting potential required bureaucratic and industrial organization, but it also required the men on the ground - from the grunts and NCOs, to the field grade officers, all the way up to Ike - to perfect the synergistic application of all that wonderful equipment. And this, as we shall see, was easier said than done.

A Brief History of the American Tank Force

In the current era, when American military spending dwarfs all its competitors and American defense contractors are household names, it can be hard to remember that for most of the country’s history it accrued tremendous benefits from not having to maintain a standing army or think seriously about war. This was true even on the brink of World War Two. While the European powers were engaged in heated internal discussions about the correct application of tanks and mechanized forces, America largely sat out the debate, owing to a variety of institutional factors.

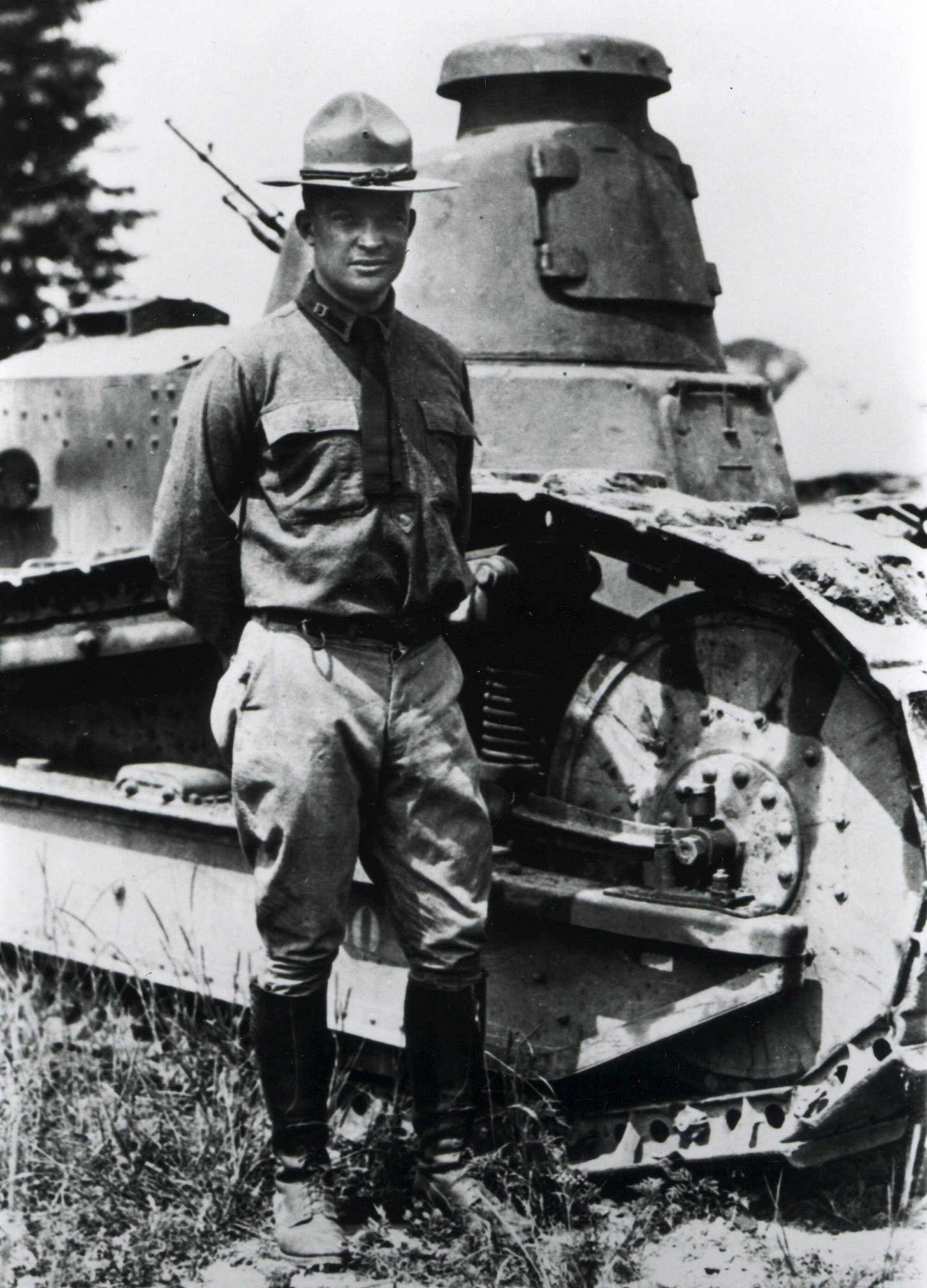

The most obvious obstacle to the development of a proper armored force and doctrine was the basic fact that the American Army did not really exist in the interwar period. After being briefly expanded to participate in the closing phase of the First World War, the Army was promptly downsized to token levels (280,000 men and 17,000 officers) with a minuscule budget that permitted neither equipment acquisition, experimental maneuvers, or robust staff work. Whatever experience the US Army gained in World War One was quickly forgotten, the tank corps was disbanded, and American officers even returned to their prewar ranks - Dwight Eisenhower and George Patton both reverted to their prewar ranks as Captains.

As a result, while the great European militaries spent the interwar period vigorously debating, theorizing, experimenting, and building out their particular visions for an armored force, the United States simply was not thinking about fighting a high intensity war on faraway continents. While Guderian, Fuller, and Tukhachevsky were planning the future of warfighting, the United States Army had only a handful of motorized units and no doctrine of armored warfare whatsoever - a series of field regulations issued in 1919, 1923, and 1939 all emphasized the infantry as the decisive arm and allocated armor to an assisting role.

In a sense, this was natural given the history of the American military. Aside from the brief intervention in World War One, the United States had fought only one high intensity continental war in its entire history, that being its own Civil War. Apart from this, all of America’s wars had taken the form of either frontier conflicts with Native American tribes or expeditionary wars like the campaigns in Cuba (1898) or Mexico (1847 or 1916). In either case, the emphasis was on tough, resourceful, and self reliant soldiers who could travel light and fight without a complicated system of logistical support or heavy weapons.

Of course, it was undeniable that mechanization would have some sort of role to play in future wars, but for American planners everything proceeded from the assumption that infantry would play the decisive role. The primary role envisioned for armor was that of a horse cavalry replacement, particularly exploitation. American tank designs from the start therefore prioritized reliability, maneuverability, and cruising range over survivability and fighting power.

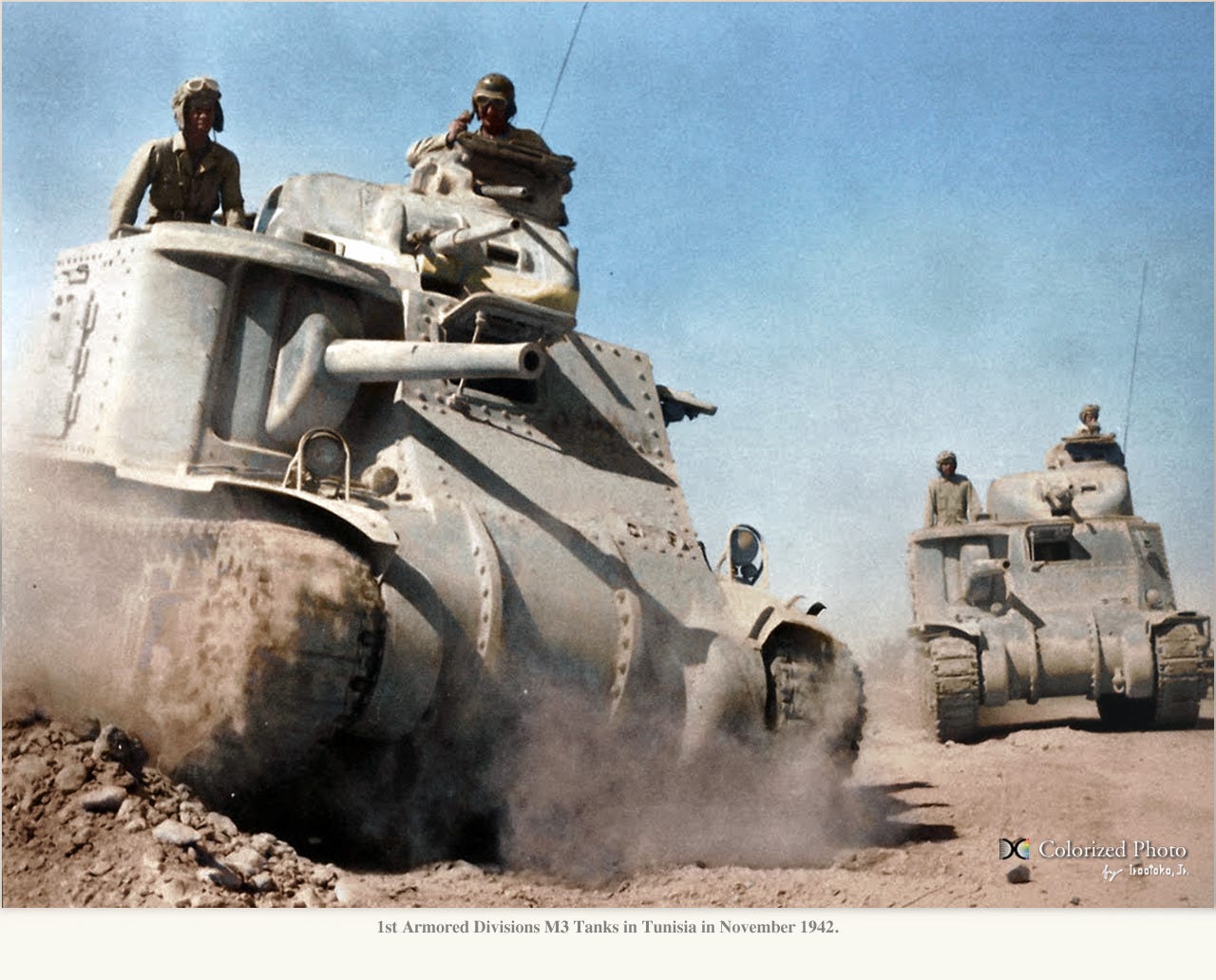

American tanks, as a rule, were significantly lighter and more weakly armed and armored than German vehicles of the same generation. Both the US Army and the Wehrmacht introduced a new medium tank in 1939: the Panzer IV weighed 25 tons and sported a low-velocity 75mm gun, while the American M2 weighed just 19 tons and had only a 37mm gun - a peashooter. Three years later, America rolled out the world famous Sherman, which matched the weight and armament of the Panzer IV, but by this time the Germans were already putting the finishing touches on the new Panthers and Tigers. America would not deploy a proper heavy tank until the final months of the war, with only a handful of the 42 ton Pershings seeing combat. Speaking very roughly, the American Army constantly seemed to be fielding tanks that were a generation behind the panzer force in terms of weight and combat power.

The upshot of all this was that American tanks, essentially until the end of the war, were overmatched by German panzers in straight up fights. Curiously, this was not initially considered to be a problem, owing to another idiosyncrasy of the infant American armored doctrine. According to General Lesley McNair - the chief of the US Army Ground Forces - tanks were not supposed to fight other tanks at all. That was to be the role of an entirely different class of vehicle - the tank destroyer. Many second world war armies would deploy tank destroyers - largely as a cheap way to put a big gun on an armored chassis - but McNair, rather uniquely, saw the concept not as a battlefield expedient but a fundamental element of armored combat. His conception was essentially to mount an anti-tank gun on top of a lightly armored and lightning fast chassis. The tank destroyer differed from the tank in that it had almost no armor at all and was armed exclusively to knock out enemy tanks. The tradeoff from armor to speed, it was envisioned, would enable the tank destroyer to pursue hit and run tactics, hunting heavier and slower enemy armor. For obvious reasons, this tank destroyer concept has been analogized to the “pocket battleship”, or battlecruiser, which was an envisioned hybrid warship which had the firepower of a battleship, but with lighter armor to allow it to run away from danger if needed.

One can see, then, how the prewar American armored doctrine was riddled with assumptions so optimistic that they might even be called naïve. McNair did not want American tanks to engage enemy armor in combat - how could this be achieved? Of course it was inevitable that Shermans would have to fight heavier and more powerful panzers - they could not simply avoid them for years on end. The tank destroyer was meant to be used solely to hunt enemy tanks, but of course it was inevitable that troops in combat would try to use it in the support role of a tank - it was after all an armored vehicle with a big gun on it. McNair’s assumption that these vehicles could be confined to such specific roles seems, in hindsight, to be folly, but early American tank designs were in the end strongly influenced by this belief that the tank and tank destroyer could fulfill compartmentalized battlefield roles. Ultimately, this was in the interwar period a small military which had neither enthusiastic armor theorists or a culture of experimentation. There were voices - like those of General George Patton - calling for the tanks, but Patton was a cavalry officer in no position to either influence tank design or conduct maneuvers to experiment with armored operations.

Then 1940 happened. In June, the Wehrmacht won perhaps the most spectacular military victory of all time over the Anglo-French armies, with the panzer divisions playing the lead role. In this precarious geopolitical environment, the United States began to militarize almost immediately. In July, the US Armored Force was inaugurated under General Adna Chaffee - initially two divisions, one of which was assigned in November to the newly promoted Brigadier General Patton. Meanwhile, Roosevelt signed the Selective Service Act into law, and by the summer of 1941 (as Germany was invading the Soviet Union) the Army had already expanded to 1.4 million men. Contrary to the popular line of thought that America was totally unprepared for war and in a completely passive stance when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the United States had begun a preparatory mobilization process at least 18 months before that date which lives in infamy. The question of whether the Roosevelt Administration intentionally provoked a Japanese attack is one we will leave for another time.

The long awaited birth of a genuine armored force also allowed the United States to attempt its first large scale field exercises. A series of maneuvers in the autumn of 1941 would allow American commanders to get their first realistic experience moving large mechanized forces in the field - and not a moment too soon. The maneuvers also served as a sort of vetting process for the general staff, with nearly three quarters of the operational level commanders (divisions, corps, and armies) being removed in the aftermath in favor of younger officers. The star of the maneuvers, though, was none other than Patton. During a September exercise in Louisiana, he took his division out of bounds - driving 400 miles in a sweeping loop outside of the designated exercise grounds, crossing the Sabine River into Texas, refueling his tanks at local gas stations, and then re-crossing the border back into Louisiana. When he arrived, unexpected and undetected, in the rear of the “enemy team”, the maneuver referees complained that he had broken the rules. Patton’s reply - that he was “unaware of the existence of any rules in war” - was perfectly on brand and confirmed his status as a rising star.

And so the United States moved towards its historical inflection point. In 1939, a country which in our own time is known for virtually limitless military spending and a permanent globe-spanning military deployment had an army smaller than Romania’s. The tank force was brand new, the equipment was subpar, the officers were green, and the doctrine was somewhere between nonexistent and wonky. Yet clearly the latent power of this country was absolutely enormous, and its industrial-logistic power had no peers. The question of the day was very simple - how could the gap be bridged between America’s world-leading power potential and the total inexperience of its armed forces? It was time to find out. When the Japanese carrier force attacked the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, it was go time. The United States was tentatively ready to try its hand at a European style war of mass armies. The question was where and when.

The Amazing Race: North Africa

One of the paradoxes of American strategy in the 2nd World War is the inverted relationship between security and operational convenience. The United States was strategically inviolable - in 1941, neither Japan nor German could actually threaten the American homeland in any meaningful way. Germany could harass American shipping with submarines and Japan could raid outlying naval bases, but American children in Pittsburgh and Boston and Chicago and Dallas and Denver had nothing to fear from either the Wehrmacht or the Japanese Navy. Yet this same strategic invulnerability also bred a measure of paralysis once America became formally involved in the war. America needed to rapidly build up its armed forces and devise a way to actually project armed force again the enemy - but how could this be best accomplished when the critical theaters were thousands of miles away, across the ocean moats?

To make matters even more complicated, there was natural intra and inter service competition for resources and operational priority, and variegated logistical concerns. As a result, America’s grand strategy in the war was somewhat more scattered than is commonly thought. For one thing, the upper echelons of command favored a “Germany First” strategy (and every history book will tell you that this is what happened). Yet in the summer of 1942 - long before any American troops got into action against Germany - the US had already won an enormous victory over the Japanese at Midway and gone on the offensive with the invasion of Guadalcanal. The Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest King, was quick to point this out - why adopt a “Germany first” strategy when they already had Japan on the run? But perhaps we should not be surprised that the commander in chief of the US Navy was more enthusiastic about a naval war with Japan than a land war in Europe.

In any case, there were many valid questions to be asked. How, where, and when should America get into the fight against the Wehrmacht? General Marshall (Chief of the General Staff) favored what he saw as the simplest and most straightforward path to victory - assemble overwhelming forces in Britain, invade France, and then steamroll into Germany. He had no interest in peripheral theaters, and thought that the essence of strategy was to build the biggest possible hammer and swing it at the enemy’s forehead. Unfortunately, it was clear from the first staff studies that this would be easier said than done. An amphibious operation promised enormous complexity with a huge amount of preparatory staff work, special training, and new equipment - it is frequently noted than in 1942 the iconic American landing ship had not yet even been designed. Marshall and his staff concluded that a mass invasion across the English Channel would likely not be possible until 1944 - so how could a “Germany First” strategy be pursued if they could not even fight the Germans for two years?

In the end, it was the British who came forward with a suggestion. Their solution was an operation that they were calling Gymnast - later renamed Operation Torch. This called for an amphibious landing in the French colonies of Morocco and Algeria, which were under the control of the German puppet regime in Vichy France. The Morocco option had obvious appeal to the British. At the time, they were stuck in a hard fight with Erwin Rommel’s army in Libya and Egypt. Gymnast/Torch would put a large force in Rommel’s rear, potentially collapsing the German position in Africa altogether. Furthermore, the Mediterranean was an area of intense strategic interest to Britain, and getting American troops into Africa was a good way to get the Americans interested in it too. Finally, Torch would allow the Americans to get experience with amphibious operations against unmotivated French collaborationist forces. The British knew very well (as did the Soviets) just how hard it was to fight the Wehrmacht, and letting the Americans slowly get their feet wet seemed like good sense.

Much of the American military leadership thought that Torch was a senseless distraction, but the President decided to agree to it. His reasoning was essentially sound. He wanted to put US ground troops into action against the Germans as soon as possible, and since Marshall’s envisioned invasion of France was materially impossible, he would order Operation Torch just to get into the fight. When Marshall and King complained that Torch was a meaningless distraction, Roosevelt asked them to submit in writing their alternative plans for an operation in 1942. They had none, and so Torch became the American operational agenda for the year simply because it was the only option.

In any case, the complexities of Operation Torch were more than enough to keep Marshall and his staff occupied. This was, after all, a major amphibious landing which would be conducted over 3,000 miles from the United States. It may or may not have been a “distraction”, but it was certainly complex enough in its own right. The ultimate objective was the critical port of Tunis - the main hub of supply and operations for the Axis forces in North Africa. Tunis was an existential position - its capture would certainly doom Rommel’s forces, and it was therefore sure to be contested fiercely, and it was a near certainty that the Germans would rush additional forces to Africa to try and save it. From the beginning, then, there was an element of a race at play - could the allies get ashore and get to Tunis before the Germans could reinforce it? It would thus have made sense to land as close to Tunis as possible, but coming too close would put the allied fleet in range of German aircraft in the Mediterranean.

The allies ended up choosing what was, all things considered, a very conservative plan, with three landing zones selected in French Algeria and Morocco. An American force under General Patton would land on the Atlantic coast near Casablanca, a British force would land near Oran, and a third fleet of mixed British and American units would land near Algiers under the command of American Major General Charles Ryder. These landing zones were relatively remote from Tunis, but they had the advantage of being free of Germans. The only defending forces would be Vichy French colonial troops - lightly armed by the standards of this war, with relatively little artillery and only a few groupings of old tanks - a token force, but certainly capable of killing. It was not even clear whether they would fight, with rumors abounding of strong sympathy for the allies.

In the end, more than enough went wrong in Operation Torch to validate the view that the United States needed to ease into the war. There were all sorts of problems. Most people can form a mental image of the famous Normandy landings, complete with the famous landing craft dropping their ramps on the beach. Torch was nothing like that - it was an affair conducted with a mismatched and motley assortment of random small craft and boats, performed by a completely inexperienced American force. Confusion and chaos were the order of the day.

The landings themselves tended to be disorganized, with navigational breakdowns and units ubiquitously coming ashore in the wrong place. One American unit that was supposed to land along a four mile stretch of beach ended up strung out over 42 miles of coastline. Many men landed without their commanding officers, and some of these lost units simply sat around on their beaches - and even took naps. In general, there was little instinct among the senior officers on site to take charge. Supply crates were not well marked - a seemingly minor issue, but one which led troops to have to rummage through boxes looking for what they needed, or simply to see what was in them.

Where the green American troops did run into enemy fire, they reacted poorly, as almost all inexperienced soldiers do. Their instinct was to drop to the ground on contact, leading a variety of American units to simply become immobilized and pinned under French fire. At one landing, an American unit even broke and fled after being counterattacked by a handful of old French tanks. Where there were real firefights, the Americans had poor coordination of arms and frequently lost contact with their officers.

Thankfully, there were two major factors in favor of the Anglo-Americans. The first was the simple fact that the defenders were not Germans, but French collaborators. Some French units did fight back to the best of their abilities, but many defected or surrendered. The choice was really up to the unit commander, and the Americans had no way of knowing which would occur until they started shooting. This made the situation highly complicated and precarious, but the upside was that there really was no centrally coordinated defense by the French - only a discombobulated and decentralized resistance. The second thing the Americans had going for them was firepower - artillery, naval support, and airpower. Patton - whose landings had gone the worst of all - ended up leaning on this as the overarching solution. Rather than try to assault the well-defended city of Casablanca, he simply sent a message to the French commander informing him that he intended to destroy the city via naval and air bombardment. The French surrendered.

All in all, Torch was a rather bizarre little operation. Derided by many American commanders as a distraction and a British scheme, it ended up teaching a valuable lesson about the complexity of amphibious landings and the learning curve faced by America’s rookie troops. Patton’s assessment was honest: “As a whole the men were poor, the officers worse. No drive. It is very sad.” Later on, he would concede that “Had the landings been opposed by Germans, we would never have gotten ashore.” But that was the entire point - perhaps, in hindsight, Patton ought to have been grateful for the chance to practice an amphibious operation in a place that was not defended by Germans. As it was, Torch left the American Army with over 500 dead, a similar number wounded, and a great deal to think about.

Of course, Torch had not been conducted simply to capture French North Africa. The point was to use this as a launching point to drive eastward towards Tunisia, into the rear of Rommel’s army. But the timing was rather serendipitous. Torch began on November 8, and it took the better part of a week to get the landing forces sorted out. Simultaneously, 2000 miles to the east in Egypt, Rommel’s Panzerarmee suffered a decisive defeat at El Alamein at the hands of General Bernard Montgomery’s British 8th Army. By November 4th, Rommel had already begun a retreat back towards Tunisia. If the allies could reach Tunis before Rommel, they could potentially trap and destroy his entire force. American newspapers were quick to proclaim that the “race for Tunis” was on.

Truth be told, the race for Tunis was rather anticlimactic, simply because the Germans were already there before the allies set out. Operation Torch came at a problematic time for the Germans - in November 1942 they were already coping with the failure of two critical offensives (Rommel’s attack on Egypt and Operation Edelweiss’s drive on the Soviet oil fields in the Caucasus) as well as the looming loss of 6th Army at Stalingrad. The news that an Anglo-American force had landed in French North Africa was therefore most unwelcome, but the Germans responded with characteristic speed and decisiveness. On November 9 - the day after the Torch landings began - Hitler announced the formation of a “Tunisian Bridgehead”, to be the cornerstone of Germany’s position in the Mediterranean. Field Marshall Albert Kesselring was put in charge, and that very day the first Luftwaffe units began to arrive in Tunis to reinforce the German position in Africa.

In a sense, then, three different forces were converging on Tunisia. One was the surge of German reinforcements under Kesselring - an odd assortment of partial units, reflecting the fact that Germany had neither substantial reserves to spare nor sufficient transport capacity to get them all to Africa. In the end, a hard working airlift managed to add some 25,000 German personnel to the African position, where they were put under the field command of the veteran General Walther Nehring.

The second force heading to Tunisia was Rommel’s retreating “German-Italian Panzer Army.” On paper this was a powerful four-corps formation with a slew of armored divisions (even if some of them were Italian), but it was heavily beat up after its long campaign towards Egypt and its defeat by the British at El Alamein. Worse yet, it had the longest road by far to get back to Tunisia. El Alamein is over 1,100 miles from Tunis as the crow flies - but the panzer could not drive as the crow flies, and retreating along the coastal road stretched the journey to some 1,500 miles, hounded all the way by Montgomery’s pursing forces. The tired, but still determined remainder of Rommel’s force would not arrive back in the Tunisian theater until early February, which meant Nehring’s little force was on its own for the time being.

That left the third force in this race - the allies. In theory, there would be little or no resistance between them and Tunisia, but they found it much harder than anticipated to immediately launch into a high speed race across the desert. There were a variety of reasons for this. One was quite simply the distance - the easternmost allied landing zone, around Algiers, was still nearly 400 miles from Tunis, and Patton’s landing around Casablanca was another 650 miles farther to the west. With the allied forces strung out along the North African coast, it was not easy to put together a large force for a drive on Tunisia. In the end, only a single British Division with a few small trailing American units could be organized to form the tip of the spear.

The other problem that the allies were about to learn about (a problem that Rommel or Montgomery would have been intimately familiar with) was the horribly difficult task of supplying an offensive in the desert. The popular image of desert warfare is one fully conducive to maneuver - endless plains of flat, hard soil that are completely open to movement. In reality, the desert immobilized armies by yoking them to their supply lines. Every drop of gasoline, every mouthful of water, every bullet, every calorie worth of rations had to be laboriously hauled forward hundreds of miles to forward units, and this process required the advancing armies to leave troops strung out along the supply line to both protect supply dumps (often from theft by the locals) and feed them forward. Multiply this problem along a thousand miles of road, and the problem becomes obvious. As Robert Citino has observed, even though there were 180,000 American troops in North Africa, at most 12,000 of them (7%) were actually at the front - the rest were strung along the enormous coastal line.

Finally, far too much allied command attention was soaked up trying to deal with the administrative and political tasks of occupying French North Africa - negotiating with French officials and local tribal leaders, maintaining order in occupied cities, and attempting to de-nazify the Vichy French regime. In particular, Eisenhower struggled to thread the needle of cooperating with the French authorities (a necessity to keep order) while dealing with criticism by the American press that he was cooperating with Nazi sympathizers.

There was a synthesis of confusion and ineffectuality - hostile terrain, tremendous supply difficulties, enormous distances, distracted commanders, and miniscule force generation. The upshot, in the end, was a major learning moment for the American military. The operation was certainly drafted with an ambitious sheen - a surprise landing in Rommel’s operational rear, followed by a rapid thrust into Tunisia to collapse the German position in Africa. Instead, the Americans fumbled the landing operation and found that they simply lacked the capability to either assemble a large maneuver element or get it moving quickly towards Tunis. Instead of a race for Tunis, they got an assortment of small and partial units cautiously creeping into Tunisia long after the Germans had arrived there.

The upshot of all this was a sobering moment for the American army when it engaged the Wehrmacht in battle for the first time. We may say “battle”, but this is being fairly generous. Skirmish is probably a better word. The allied spearhead - optimistically named “First Army” but having only a division’s strength at best - probed into Tunisia and began to run into Nehring’s forces, which were in the process of trying to establish a perimeter in the Tunisian mountains. A variety of meeting engagements were fought, with the Germans mostly getting the better of the allies, for two reasons. First, the Germans were by far the more experienced warriors in the fight, and secondly they were fighting relatively close to their airfields and supply bases, while the Anglo-Americans had long since left their bases behind.

The Americans did have a few good moments in their opening action against the Germans. On November 25, 1st Battalion of the American 1st Armored Regiment managed to sneak right through a gap in the German perimeter and came upon an undefended German airfield near the little town of Jedeida. When the lead elements came over a hill and saw the German airfield sitting in front of them, Major Rudolf Barlow radioed battalion command for instructions. “What should I do?” He asked. “For God’s sake, attack them. Go at them”, came the reply. A moment of silence, and Barlow answered: “Okay, fine.” Wielding light M3 Tanks - the trusty “Stuart” - Barlow’s tank company rushed the airfield and overran the stunned German ground crews, destroying over 20 aircraft and sizeable stocks of fuel and ammunition. The Jedeida airfield raid was the first signature achievement of the American tank force, and the high mark of America’s campaign in 1942.

Unfortunately, another painful lesson was in the offing. With the little allied force probing its way towards Tunis, the Germans were ready to teach them about battlefield aggression and decisive movement.

The forces at play were truly miniscule, especially in light of the colossal armies slugging it out on the eastern front. The allies had less than 12,000 men, while the German commander, General Nehring, had only partial elements of a single Panzer Division and some Luftwaffe airborne troops: in all, perhaps 9,000 men and 64 tanks, of which 4 were Tigers. Nevertheless, the signature elements of German operational art were to be demonstrated in miniature. Nehring divided his force into several compact battlegroups and pounced on the lead allied brigade at the town of Tebourba, slamming them from multiple angles - a tiny but effective application of concentric attack, which overwhelmed the allied forces and created a headlong flight. An American armored brigade which was rushed in to stabilize the situation ended up launching a series of headlong attacks across open ground, and was almost completely destroyed by the small German panzer force.

The haphazard and miniaturized campaign in Tunisia confirmed what should have been obviously by the middle of November - the allied plan to seize Tunis in a coup de main had turned into a complete bust. In the context of this enormous war (and certainly compared to the scope of the Nazi-Soviet War), the forces that Germany had airlifted into Tunisia in response to Torch were essentially miniscule, but given how small allied force generation was at this point, Nehring’s little force was more than enough to protect Tunis in the short run. Facing up to the failure of the initial drive on Tunis, Eisenhower chose to spend the winter consolidating a line along the mountains of Central Tunisia (called the “Dorsal”) and prepare for a full scale campaign in 1943 to drive the Germans out of Africa.

America’s entry into the war on Germany was off to an inauspicious start. Contrary to the popular and patriotic perception of Americans, the American Army was no better prepared to cope with the Germans on the tactical and operational level than any of the Wehrmacht’s other opponents had been. When Nehring’s little force smashed them at the micro-battle of Tebourba, it demonstrated simply that modern warfare was an immensely complicated enterprise which the Germans had been thinking about and practicing at a high level for years. Whether Polish, French, British, Soviet, or American - nobody had a good time in their opening rounds with the Wehrmacht. What matters, of course, is that this was not a one-round war.

In contrast, the American Army suffered from some of the same sorts of problems which plagued the early-war Red Army (a bitter pill for patriotic Americans to swallow, but true nonetheless). American command tended to break down at the operational level, devolving action to small units like battalions and even companies. In general, there was an inability to coordinate both large units and combined arms. The instinct among infantry was to go to ground and dig in, while the armor took the opposite approach, preferring spirited head on charges which were ill advised given the qualitative superiority of the German equipment. Needless to say, apprehensive infantry and reckless armor do not synergize well, and dysfunctional command and control did nothing to reconcile them.

America Meets the Panzer Package

The failed drive on Tunis had produced a rather unusual situation map - but then again, war in North Africa conspired to produce strange dispositions.

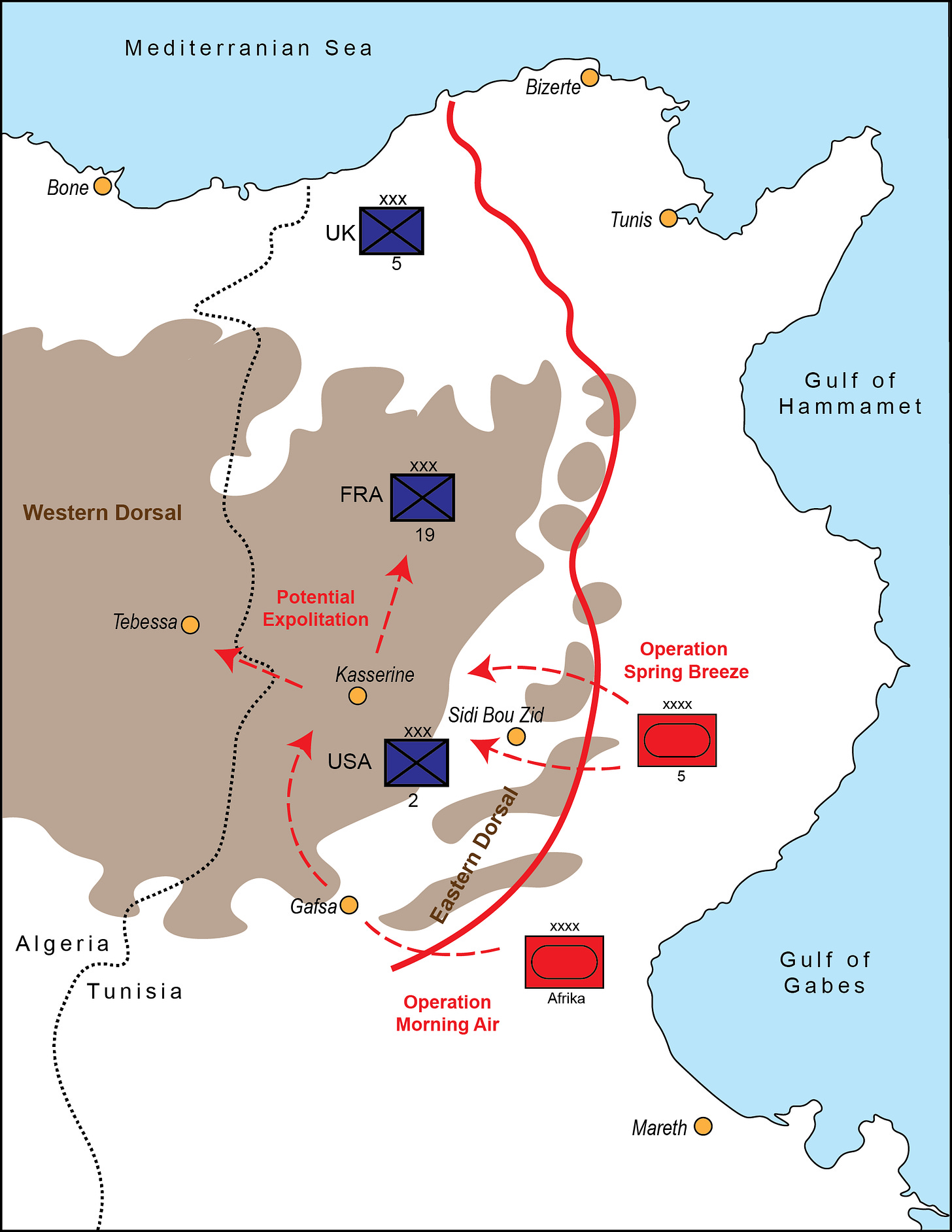

After receiving a mauling at Tebourba, the allies consolidated a line along the dorsal in central Tunisia - all in all, an aggressive position which confined the Germans to a slim bridgehead along the eastern coast. What made this so peculiar was the fact that the position was relatively long (nearly 150 miles), despite the paucity of forces on both sides. To solidify the position, Eisenhower had to deploy French colonial troops (lightly equipped and no match for the Wehrmacht) in the center, while feeding the newly deployed American 2nd Corps, under General Lloyd Fredenhall, on the right. All of this took time - after all, the initial allied Spearhead (British 1st Army) had come into Tunisia with scarcely a division worth of discombobulated small units. Thus, while the maps may show a nice solid line running through the middle of Tunisia, for most of December this line was thinly patrolled.

Meanwhile, on the German side, Nehring’s force continued to receive reinforcements - not a tremendously great number, of course, but enough to eventually receive a designation upgrade to “Fifth Panzer Army”. It also received a new commander - Nehring was removed for “panicking” after the successful American raid on his rear airbase, and replaced by General Hans-Jürgen von Arnim. Arnim was a typically tough, quick moving, and attack-oriented German commander - indeed, the existence of many hundreds of men just like him was a foundational element of German military prowess. Arnim would spend the holidays chipping away at Eisenhower’s line with lively skirmishing, but a to pursue a real operational victory he would have to await the arrival of Rommel’s Panzer Army Afrika, which was still painstakingly retreating from Egypt.

Rommel’s arrival in the Tunisian theater in February produced a genuinely unique operational calculus that would not be repeated again. Rommel’s army was tired, chewed up, and in a general state of some disrepair, but it was still a powerful force. With Arnim’s 5th Panzer Army included in the calculation, the Germans actually had superior combat power in the theater - at least until Bernard Montgomery (pursuing Rommel from Egypt) arrived in the rear. For at least a couple of weeks, then, Rommel actually had a small but meaningful numerical advantage over the Anglo-Americans - something no other German field commander would ever really be able to say. The Germans also, for the time being, could still draw on Luftwaffe support powerful enough to intervene and exert an influence on the battle. Thus, Rommel had what was, all things considered, a truly unique opportunity to achieve an operational victory. This would be the first, and really only time that the Americans would fight something like the full Wehrmacht package, complete with a competitive air force and functioning panzer divisions. Thereafter, the Luftwaffe was inexorably chased from the skies by the ascendance of the US Army Air Force.

The Axis had a powerful package in Tunisia - 100,000 men, four fully operable armored divisions (one of which was Italian) boasting hundreds of tanks, and a pair of hard driving and aggressive commanders in Rommel and Arnim. This latter element was important, because what the Axis did not have was time. Montgomery’s army was slowly but surely creeping along the coast in pursuit, and when it arrived the Axis would not only lose their edge in combat power but also face an attack in their operational rear. This created a microscopic variant of the classic German military conundrum - facing enemies on all sides, there was an imperative to move quickly to attack and defeat them in sequence.

The solution that Rommel and Arnim came up with was a classic German operational formulation. The main target would be the American 2nd Corps on the southern end of the allied line. Two advantages would accrue - first, the Americans were viewed as a fundamentally green force that the Germans could reasonably hope to shatter; secondly, by attacking the southern end of the line the Germans would be able to roll up towards the north, creating a pocket against the coastline. Arnim would start things off with Operation Spring Breeze - a direct panzer assault against the American forward position at Sidi Bou Zid. This would create a major threat to the American line and hopefully draw in American reserves, at which point Rommel would launch Operation Morning Air, which would cut like a sickle across the base of the American line, driving up through Gafsa towards the Kasserine Pass. At this point, the Axis would have a large panzer force in the heart of the American position and have their choice of follow up targets - they could drive on the American command and supply hub at Tebessa, or even head for the coast and try to envelop the French and British forces.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.