The Napoleonic Wars subjected Europe to prolonged warfare of an intensity and geographic scope that was, at the time, without precedent. The Thirty Years War had offered a foretaste of the damage that general continental conflict could inflict, but the scale was far more limited, with much smaller armies fighting with less destructive weaponry in more confined theaters. The Napoleonic Wars, on the other hand, generated battles of hundreds of thousands of men, with major campaigns taking place from Iberia to Moscow, and from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. After 23 years of nearly continuous warfare, some five million Europeans had died, and many millions more were impoverished and destitute. Armies on all sides exacted a horrible economic toll on the civilian populations of the theaters - stripping barns and larders bare, consuming livestock, conscripting young men, requisitioning horses and wagons, and levying taxes. Trading economies were devastated by the British blockade of the economy and Napoleon’s counter-blockade.

If anyone thought that the end of war would bring a return to stability and safety, they were tragically mistaken. In the April of 1815, as Napoleon was enjoying his brief return to power prior to his final battle at Waterloo, a volcano called Mount Tambora began erupting in the Dutch East Indies (modern day Indonesia). The conflagration threw an enormous dust cloud into the sky, along with a tremendous amount of sulfur, which clouded the atmosphere globally and reduced summer temperatures by several degrees across much of the world the following year. As a result, Europe’s first year without war, 1816, was also “the year without a summer”. Crop yields across Europe were both poor (as little as a quarter of normal harvests in some places) and late. Disease and bread riots followed famine, as they always do.

Little wonder, then, that the 19th century was a time of tremendous change in Europe. The pressure on European institutions was enormous. It would be difficult to enumerate all the ways that Europe was transformed between the fall of Napoleon in 1815 and the beginning of the next continental war in 1914 - mentioning only the end of serfdom, the Industrial Revolution, and the rise of mass literacy and mass politics should suffice to hint at the profundity of the change.

Military affairs were hardly exempt from the fundamental transformations that swept across the world in the post-Napoleonic years. For military thinkers and planners, the challenge lay in coping with one revolution as another was taking place. Warfare had changed in fundamental ways during Napoleon’s wars, in large part due to Napoleon’s own operational art and organizational concepts. Military staffs sat down after the war to digest these changes - studying and systematizing Napoleonic methods - yet while they worked at this task, the emergence of railroads, the telegraph, rifled firearms, and explosive artillery shells threatened to dump yet another military revolution on their heads.

Military affairs in the 19th century, therefore, were subject to countervailing forces pulling armies in two different directions. Military planners dutifully examined the past, even as industrialization pulled them into the future. Armies were caught between two revolutions.

As generals struggled to cope with these changes, they remained wedded to Napoleon’s core vision of a climactic set piece battle, using the offensive to pin and destroy the enemy’s main field army. The dream of decisive battle remained as seductive as ever, even as it became ever more elusive. Two military systems in particular would remain committed to fluid, mobile, set piece battles - those of Prussia and the United States of America. In this entry, we will examine America’s futile search for decisive battle in the 19th Century, before taking up the Prussian case in the next essay.

Jomini in Mexico

Apart from Clausewitz, none of the post-Napoleonic military theorists are as prominent as Antoine-Henri Jomini. A curious social relic in many ways, Jomini was one of the last notable members of the pre-nationalistic aristocratic military class - professional officers who could flexibly move about, offering service to one army after another. Swiss by birth, Jomini served first in Napoleon’s Grande Armee (as a protege of Marshal Ney) before transferring his service to the Russian Army in 1813, to the effect that he held the rank of general on both sides.

While Jomini, like Clausewitz, was a veteran officer who became a post-war military theorist, the similarities essentially end there. While Clausewitz was focused on the transcendent philosophical essence of battle, and could be abstract to the point of borderline mysticism, Jomini was intensely practical, and his seminal work, Summary of the Art of War, reads like a user’s manual.

Jomini was intensely interested in creating a systematic framework for war; reducing the enterprise as much as possible to a structured taxonomy with a system of governing principles. His notion of war was intensely scientific and rational, and it aimed to discover procedural rules that might “solve” warfare, in that the precisely correct course of action could be almost formulaically determined in any situation.

Much of Jomini’s specific analysis has aged poorly, in that (unlike Clausewitz) he was focused on the specific systems and principles accruing to war in the 19th century. However, one area where Jomini’s impact has endured is in his taxonomy and language of war. Jomini famously devised an exhaustive set of terminology to describe the geometric dynamics of the battlespace. In particular, he is famous for his preoccupation with “lines”.

As Jomini saw it, the Theater of Operations (he was one of the first to use this phrase) was a geographic space that mediated between two critical points. The first was the Base of Operations, which is the origin of the armed force - the place from which it receives supplies, reinforcements, and direction. The second critical point is the Objective Point, which marks the critical point upon which the army aims to direct fighting power - this could be the enemy’s capital, his own field base of operations, or some other decisive point.

Jominian thinking frames a military operation as a projection of force which comes out of the Base of Operations and moves towards the Objective Point. As the armed force projects farther from its Base of Operations, it weakens, because its connection to supplies and reinforcements becomes longer and more tenuous. This connection is what Jomini calls the Lines of Communication (and now everybody else calls it that too). Because Lines of Communication become weaker the longer they are, it becomes necessary for the army to establish a Pivot of Operations, which is some held point that magnifies force projection farther away from the base of operations (think of a Pivot as forward basing - the supply dumps that power forward operations).

Running through Jomini’s entire lexicon can be exhausting. He has seemingly endless verbiage, much of which is so alike that it ends up confusing, moreso that clarifying (Jomini, for example, distinguished between the Pivot of Manuever, Pivot of Operations, Strategic Point of Manuever, and Geographic Strategic Point). In all, this makes him something of a dense, overly technical, jargon-obsessed author.

On the whole, however, Jomini’s system of war was essentially Napoleonic. He strictly emphasized decisive battle, particularly the motif of bringing concentrated fighting power to bear on a decisive point (Schwerpunkt). To support this aim, he demanded meticulous attention to supply lines and basing, so that maneuver could be supported across large spaces. This thinking gave priority to offensive action, the spacial arrangement of the operation, and set piece battles in the Napoleonic style. Jominian warfare is a top down and battle-centric system, which idealizes regularized columns and formations fighting decisive battle in the Napoleonic style.

Jomini, who was born in Switzerland, served in the French and Russian armies, and participated in battles all across Europe ended up becoming particularly influential in a place that he never visited - the United States. This fact is owed largely to one of America’s greatest military men of all time: General Winfield Scott.

Winfield Scott’s military and political careers could hardly have been more different. As a political figure, he was a perennial loser, failing on three different occasions to win the Whig Party’s presidential nomination before finally succeeding, only to lose the election to Franklin Pierce. Despite decades in American public life, he never won a single election to public office. In direct contrast, he also never lost a single battle in his career as a commanding officer, in a career which spanned a variety of frontier disputes, the War of 1812, and most famously the Mexican American War.

The pinnacle of Scott’s military career was his famed campaign to capture Mexico City in 1847. The campaign marked the climax and conclusion of the Mexican-American War, and was, inasmuch as such a thing is possible, nearly a perfect military operation. Scott’s army was transported across the Gulf of Mexico and landed near the fortress port of Veracruz on March 9, 1847, in the first amphibious operation in American history. Artillery was hauled ashore, and a battery was prepared under the instruction of a young artillery officer named Robert E Lee. On March 29, the fortress at Veracruz fell.

Scott would lead his army on 200 mile march into the Mexican heartland, fighting several pitched battles with the Mexican army and winning each one decisively. At the Battle of Cerro Gordo, the infamous Antonio López de Santa Anna (America’s much detested villain of the Alamo) entrenched his army in a mountain defile, in conditions not dissimilar to the ancient battle of Thermopylae. Facing a numerically superior enemy defending a natural chokepoint, and operating on unfamiliar and hostile terrain, Scott contrived a way to haul cannon up a ridge to fire down on the Mexican positions. Normally, attacking a larger enemy force in an entrenched position is a costly endeavor, but Scott shattered the Mexicans, killing over 1,000 and capturing 3,000 more at a cost of a mere 63 American lives.

The rest of the campaign followed a similar pattern. Scott blasted his way directly into the Valley of Mexico, cleaned up what remained of the Mexican Army in a series of battles around the capital, and entered Mexico City victorious on September 15. In less than six months, leading an expeditionary force of a mere 20,000 men, Scott had waltzed right into the Mexican heartland and swatted aside every attempt to obstruct him with relative ease.

While it is easy to dismiss the campaign as a superpower crushing a weaker neighbor, Scott’s operation was a genuinely outstanding military achievement. Operating far from home in an era long before America perfected the logistical apparatus needed to support expeditionary warfare, Scott solved a variety of different military problems, showing off a full operational playbook: an amphibious landing, reducing a fortress, set piece battles, and assaulting major urban areas. The campaign made him an acclaimed military hero at home, and the de facto revered elder of the American military establishment.

What matters for our conversation here, however, is the fact that Winfield Scott was a disciple of Jomini and Napoleon. Scott was a vocal advocate of what he called the “French School” of military doctrine, and he was known to bring a copy of Jomini’s book with him on deployment. The campaign in Mexico, furthermore, represented fastidious adherence to Jominian principles (a fuller reading may be obtained here). Meanwhile, at West Point, Jomini’s book was the only work on military strategy used in the curriculum, and officers spent a full year under the tutelage of Professor Dennis Mahan learning Jominian principles and studying Napoleon’s art of war. Mahan even hosted a “Napoleon Club” dedicated to analyzing Napoleon’s campaigns, and in one of his teaching texts noted the following:

The systems of tactics in use in our service are those of the French; not that opinion is settled among our officers on this point; some preferring the English. In favor of the French, it may be said, that there is really more affinity between the military aptitude of the American and French soldier, than between that of the former and the English; and that the French systems are the results of a broader platform of experience, submitted to the careful analysis of a body of officers, who, for science and skill combined, stand unrivalled.

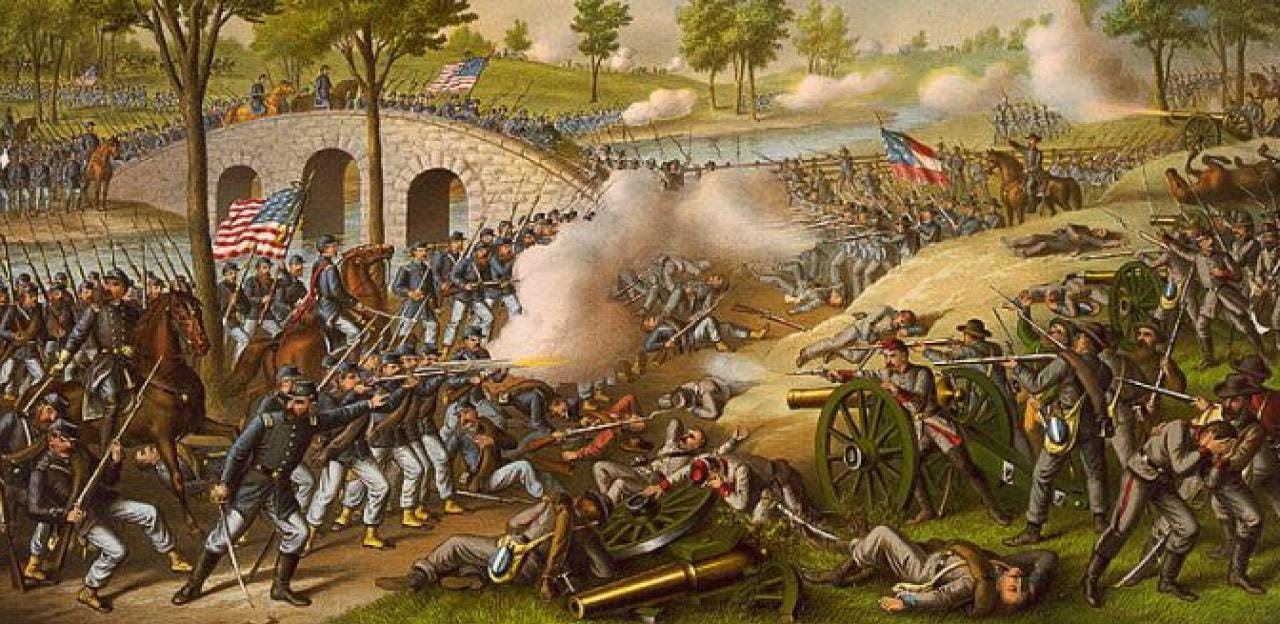

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, both the Union and the Confederacy drew their senior commanders from more or less the same institutional pool of officers. Robert E Lee, Stonewall Jackson, George McClellan, Ambrose Burnside, James Longstreet, Joe Hooker, Ulysses S. Grant - all of these men were graduates of West Point’s Jominian curriculum and veterans of the Mexican American War. As a result, there was a shared pseudo-Napoleonic presupposition as to how war was fought, which placed decisive battle, maneuver of large, stereotyped units, and the offensive at the center. Thus, both Union and Confederate generals entered the war prepared to fight large set piece battles featuring bayonet charges and massed columns of infantry, just as Napoleon had four decades prior.

It would be an exaggeration to say that the officers of the Civil War were explicitly thinking about Jomini and Napoleon as they fought the war. Certainly, we should not say that Grant and Lee were consulting Jomini’s Art of War as they conducted their campaigns, or that they were marking their maps up with Jominian labels and terms. But the victory in Mexico and the curriculum at West Point conditioned them to think about war a certain way, and as a result the Civil War was undeniably recognizable as a Napoleonic conflict on the tactical level, with massed blocks of infantry in close order, clouds of skirmisher screens, lines exchanging volleys, and officers willing to take recourse to the bayonet charge. The result of these “French School” tactics, as Winfield Scott would say, when implemented with newer forms of weaponry and by ever larger masses of men, would be a level of carnage previously unthinkable for Americans.

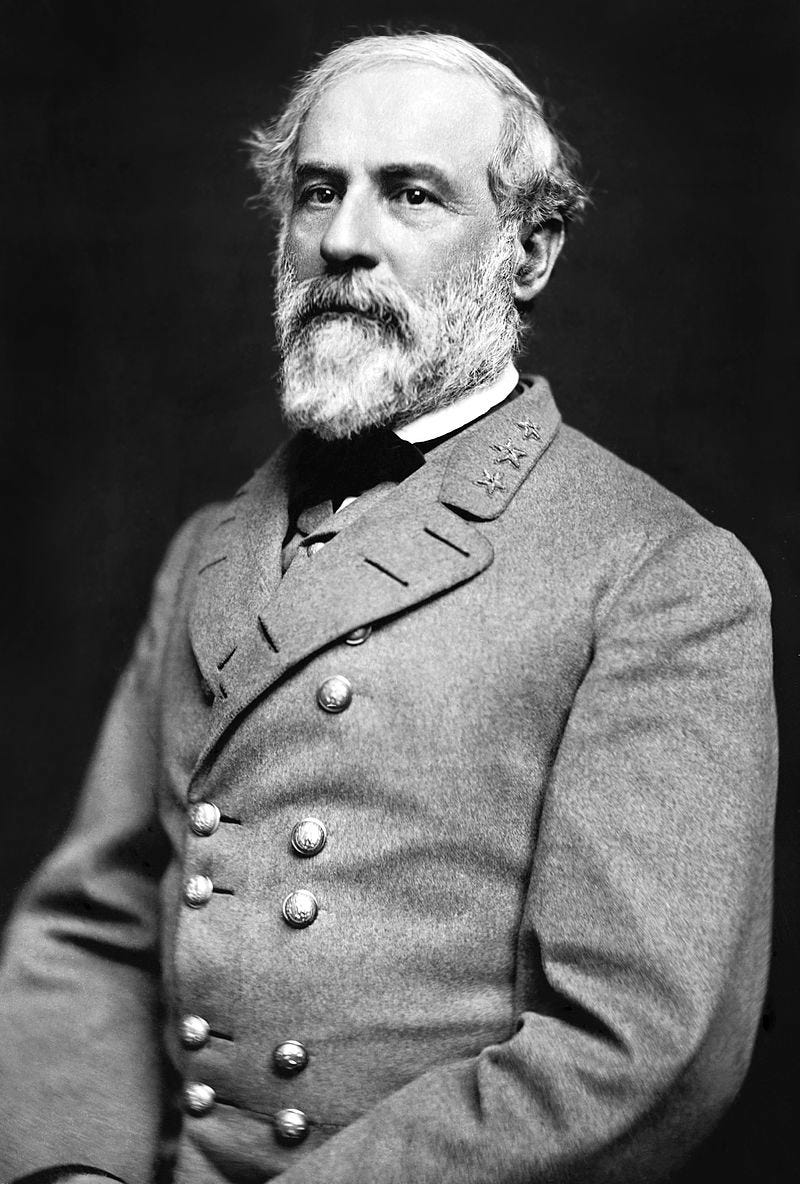

Robert E Lee’s “Perfect Battle”

Few figures in American history provoke such vociferous debate as the legendary Confederate General Robert E Lee. To some, he is the scion of America’s gentile aristocratic class, the personification of honor and duty, and one of America’s greatest field commanders. To others, he represents carnage wrought over the right to own another human being.

The great fortune of being interested in military history is that one is able to forgo such fruitless debates. Warfare retains a technical dimension above and beyond its moral aspects, in a manner akin to engineering. Of course it would be foolish to deny that warfare involves moral adjudication, but in examining the campaign as a technical exercise we are free to put aside the question of whether or not Robert E Lee was a “good man” and simply think about how he and his adversaries attempted to destroy each other on the battlefield.

Incidentally, Lee’s legacy as a commander is nearly as muddled and difficult to parse out as is his standing as a moral actor. This is due to the huge number of confounding factors. Lee was ultimately defeated, but this seems to have been largely inevitable due to the generally impossible strategic situation that faced the South, which was hilariously, insurmountably outgunned by the North’s much larger economy and population. It is generally agreed that Lee conducted himself bravely and, overall, skillfully in the face of an unsolvable strategic problem. However, it is argued in turn that much of Lee’s battlefield success was owed to the rank incompetence of his foes. Abraham Lincoln famously tried and failed for the first three years of the war to find even a modestly competent and ambitious commander, and in the process burned through several failed generals.

One battle in particular, however, may serve to distill a great deal of the Civil War’s military dimension and make apparent the larger issues. This battle reveals Lee’s undeniable skill, imagination, and aggression as a commander, but it also demonstrates why the type of war that he was attempting to fight was fundamentally unworkable.

The Civil War’s military dynamics were shaped by a geographic idiosyncrasy - namely, that the capitol cities of the combatants (Washington DC and Richmond Virginia) were only 90 miles apart. Much of the war was fought, therefore, with major armies (the Union’s Army of the Potomac and the Confederacy’s Army of Northern Virginia) loitering in close proximity to each other, making repeated efforts to reach the other’s capital. In the broadest sense, the narrative structure of the Union’s war effort was Abraham Lincoln’s frustrating search for a general who could get the powerful Army of the Potomac to Richmond. The Union would make four failed attempts to take Richmond in the first two years of the war (1861 and 1862). The final failure, led by General Ambrose Burnside, came to a horrific end when the Union army was mauled at Fredericksburg, Virginia in December, 1862.

Only too happy to be done with what had been a disastrous year, Abraham Lincoln made two significant changes as 1863 began. The first was to change the strategic objectives in Virginia. Instead of aiming to capture Richmond, Lincoln chose to prioritize the destruction of Lee’s Army - a thoroughly Napoleonic conception. The second change was to assign this task to Major General Joe Hooker, who took command of the Army of the Potomac on January 25.

Hooker earned high marks for his capable administration of the army in the early months of the year, giving his troops much needed rest and discernably restoring morale (which had been very low by the time Burnside left his post). This is an entirely different thing than meeting Lee’s army in battle and destroying it, but by the spring months Hooker had successfully restored the army to potent fighting shape.

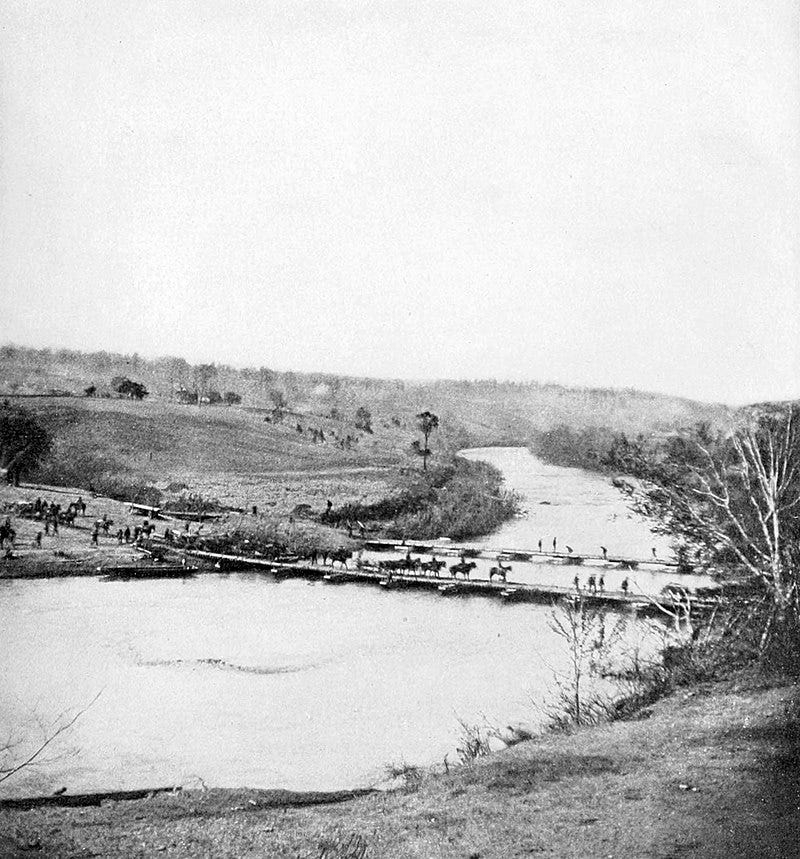

The general disposition of forces strongly favored the Union. Hooker had just over 130,000 men at his disposal - more than twice Lee’s force, which numbered a mere 60,000. The two armies began the year staring each other down across the Rappahannock River near Fredericksburg, right where Burnside’s offensive had been stopped the previous year. The gap between the two armies’ main camps was less than ten miles.

Hooker devised what was, on paper, an excellent operational scheme. He planned to leave 40,000 men on the contact point at Fredericksburg to pin Lee’s army in place. This would allow him to take a powerful grouping of over 50,000 men, march some seven miles east, and cross the Rappahannock behind Lee. This flanking march would be complicated somewhat by the presence of an immensely thick wooded area (simply called “The Wilderness”), but once Hooker emerged from the wilderness at the hamlet of Chancellorsville, he would have Lee firmly trapped in a double envelopment.

The plan was simple and sound, and would leverage the Union’s overwhelming numerical superiority to swallow Lee’s overmatched force in a steel clamp. Hooker was confident. “My plans are perfect”, he said. “May God have mercy on General Lee for I will have none.”

The opening of the Chancellorsville campaign went off without a hitch for the Union. Leaving a powerful pinning force at Fredericksburg under General John Sedgwick, Hooker successfully moved his flanking force across the river and concentrated them on Chancellorsville, setting up his headquarters in the mansion there. With Sedgwick’s own powerful grouping of 40,000 men keeping up the pressure across the river, Hooker was confident that Lee would be unable to escape the trap which was now prepared.

Instead, Lee violated every apparent rule of military orthodoxy. Conventional wisdom dictated that it was suicidal to divide one’s forces when outnumbered, as this would merely dilute an already outmatched army. Lee, however, did precisely this. Faced with a 40,000 strong Union pinning force at Fredericksburg, he left his own smaller pinning force (a single division under General Jubal Early) to hold back Sedgwick, and wheeled the entire remainder of his army - some 53,000 men - westward to confront Hooker’s flanking force.

Lee’s response to Hooker’s flanking maneuver was one of the most audacious and risky decisions in the annals of warfare. Having divided his force to fight a double battle in the face of Hooker’s attempted envelopment, Lee now divided his force yet again. He sent II Corps, under the command of the legendary Stonewall Jackson, on an enveloping march of its own - snaking around Chancellorsville to Hooker’s own unprepared right flank.

Lee’s force was now divided into three separated bodies, the largest of which was Jackson’s corps at 26,000 men. These three forces, fighting independently, were all at risk of being crushed if they were caught by Hooker’s much larger bodies. However, Hooker at this point displayed appalling indecision. Having taken the initiative with his flanking march across the river, and despite possessing much larger and better armed forces, he inexplicably withdrew into inaction, holding his forces in a defensive shell around Chancellorsville. This pathetic inactivity allowed Jackson to complete his march and slam into Hooker’s dangling right flank. Jackson’s counterattack built up tremendous momentum due poor communication among Union units, and left Hooker’s position irretrievably mangled.

Lee had stolen the initiative back from Hooker, but the day was not without blemish. On the night of May 2, General Jackson went out to conduct personal reconnaissance without properly informing his men and was shot by his own picket lines. He would die from the wounds the following week. The loss greatly affected Lee, who valued Jackson’s battlefield aggression and his instinctive ability to understand Lee’s operational thinking, but there was little time to mourn at the time. The battle was still ongoing.

The situation was still operationally very difficult for Lee, even if the counterattack on the 2nd had helped to stabilize the situation. Now, the more immediate problem was that the other large Union force - the 40,000 strong pinning force at Fredericksburg under General Sedgwick - was now forcing its way across the river. General Early had a mere 10,000 men to hold the line, and Lee had given him orders to withdraw if he was heavily attacked. After several costly assaults, Sedgwick finally broke Early’s line and forced a retreat on May 3.

The basic problem for the Confederates was Mathematical. The Union force consisted of two bodies of sufficient size to engage Lee’s entire force. Had these two bodies moved together, Lee could have been crushed between them. Unfortunately for the Union, Hooker was not proving to be substantially more competent than his predecessors. After the mauling that he took on May 2nd and 3rd, he again withdrew into passive defense and inactivity. This allowed Lee to once again break off contact and wheel back in the other direction to attack Sedgwick’s force. Hooker had boasted that he would show Lee no mercy, but his indecisiveness and passivity in combat was merciful indeed, as it allowed Lee to engage the two Union bodies one at a time.

With Hooker sitting behind his defenses, Lee was free to peel off multiple divisions to block Sedgwick’s advance and drive him against the river. By May 5, the Union forces were both reduced to a pair of separated semicircular defensive shells with their backs against the river. Facing a vicious Confederate attack, and receiving neither clear orders nor assistance from Hooker, Sedgwick decided he’d had enough and withdrew back across the river. Hooker, in a fitting end that encapsulated his indecision and cowardice, decided to take a vote from his senior commanders as to whether they should retreat or continue the operation. The officers voted to fight, but Hooker retreated anyway.

The Battle of Chancellorsville was, in hindsight, a rather odd affair. Hooker, who was literally nicknamed “Fighting Joe”, devised what was in fact a bold, decisive, and potentially unstoppable operational plan, then fumbled the entire battle away because he proved incapable of decisive action once guns were actually fired. The opening movement was successful and put Lee’s force right in the middle of two powerful bodies that could have crushed him. Instead of doing so, Hooker withdrew into a defensive position on May 1, giving Lee the opportunity to regain the initiative. Lee, who unlike Hooker was gifted with clear headed decisiveness under pressure, took this opportunity and used it to bash the much larger Union army.

Chancellorsville has long been considered Robert E Lee’s signature battle. This was the battle in which he was the most outnumbered, in which he took the most operational risk, and in which he was challenged by the most sophisticated Union operational scheme to date. He demonstrated lighting quick decision making in the face of Hooker’s flanking maneuver, refusing to allow himself to become paralyzed by the enemy’s movements (as Hooker did). It has been described by some as “Lee’s Perfect Battle”, and the appellation is probably fair. Certainly, there is a certain sublimity to Lee’s movement. Hooker planned to pin him in place and flank him, and Lee repulsed this by in turn pinning and flanking Hooker’s flanking force. The flanker became the flanked, and the rest is history.

And yet… Chancellorsville was a disaster for Lee’s army.

The movement of the units on the map is stunning. From the perspective of operational planning and wargaming, it is hard to conceive of a better scheme than what Lee put together under fire. Yet, when one looks at the colored blocks moving around on the map, one must consider what happened on the tactical level when those blocks smashed into each other.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.