It is easy to point to a variety of inventions that “revolutionized” warfare. From the exploding shell, to the telegraph, to the railroad, to the internal combustion engine, to the airplane, warfare and battle are continually reinvented to the point where they exist in an essentially fluid state. Nevertheless, if one were to point to a single technological development which marks a clear “before and after” watershed moment in the history of war, it would have to be the widespread introduction of standardized firearms, specifically muskets and cannon.

The use of muskets and field artillery drastically changed both the face of battle and society. Armies were suddenly able to bring to bear a level of firepower hitherto unimaginable, which swept equipment that had been the mainstay of war - mail and plate armor, pikes, and the bow and arrow - irrevocably from the field.

Two armies of the medieval era - the Mongols and the English - had at times enjoyed a decisive battlefield edge in the form of superior ranged firepower. But these advantages had come from their possession of unique cultural artifacts (the steppe cavalryman’s recurve bow, and the English longbow) which took a lifetime of training to master and could not be easily imitated. No German prince could simply decide that he wanted an army of Mongol style cavalry archers. Musket and cannon, however, could theoretically be available to any state, if it had the fiscal and bureaucratic machinery to acquire the weapons and recruit and train the men.

If firearms changed the face of battle, then they also changed the nature of the warrior. Armies were transformed into bureaucratic institutions and genuine arms of the state. The ancient prerogatives of the warrior classes and armed subcontractors - the knights and mercenaries of the world - were destroyed, and the descendants of the knights became the officers in professional, standardized armies, fundamentally transforming the relationship between the state, the elites, and the citizenry. The great British military historian, J.F.C Fuller, famously wrote that “The musket made the infantryman and the infantryman made the democrat” - foreshadowing that as armies grew in size and necessarily recruited ever larger proportions of the young male population, popular political participation with the state necessarily grew as well. As the Romans well knew, there are few forms of participation in political life as intense and meaningful as military service.

The military transformation of Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries would indeed change virtually all aspects of political life. For military planners, however, it merely complicated and added new difficulties to the ancient problem of battle. Firearms radically altered the geometry of battle - changing not just the way individual soldiers fought, but also how they were arranged, moved, and governed on the field. In this entry of our series, let us contemplate the changing geometry of battle in the early era of massed firearms, and discover how commanders coped with the new technology, marrying the growing firepower of their armies with the ancient quest for asymmetry through maneuver.

Swedish Supernova

Few topics can make even dedicated students of history shudder so easily as the Thirty Years War. This conflict, although one of the most significant events in European history, presents a nightmarishly tangled affair. Fought between 1618 and 1648, the war was a morass of seemingly disparate and marginally connected sub-conflicts with a headache inducing roster of belligerents. Even 400 years later, the conflict still militates against clean narration.

The entire structure of the war is rather odd to contemporary readers. It was an intensely religious conflict, with the central structure of the war, broadly speaking, appearing to be an alliance of Protestant states against Roman Catholics under the broad leadership of the Hapsburgs. Yet the war also had more recognizable great power aspects to it, notably the fact that Bourbon France, although a firmly Catholic country, sided with the Protestants. There is thus a strange duality, with a more ancient sort of religious war layered on top of a classic great power rivalry between Bourbon France and the Hapsburgs.

Another reason the Thirty Years War is something of a nuisance to write and read about is the somewhat unfamiliar - and extremely long - roster of warring parties. The war can properly be called the first of five continent-scale wars in modern Europe, the others being the Silesian Wars (1740 - 1763), the French Wars (1792-1815), and the First (1914-1918) and Second World Wars (1939-1945). Yet, unlike the following conflicts, the Thirty Years War was not fought by the usual suspects. Neither Britain nor Russia participated, while states that are largely unfamiliar to us, particularly German states like Saxony, Hesse, and the Palatinate, played prominent roles. The war also saw the heyday of formerly great powers that were either in, or about to enter their decline phases, like the Dutch Republic and Hapsburg Spain. It is, to be sure, slightly odd to read about a cataclysmic European war where England did not participate but the Dutch played a central part, and to this is added the infuriatingly complex internal geography of the Holy Roman Empire.

All things considered, then, the Thirty Years War was an ambiguous sort of dual religious-geopolitical struggle fought between somewhat unfamiliar and confusing alliances, across a wide and disconnected theater, through a huge number of relatively small and indecisive battles. The armies involved were generally small (rarely more than 20,0000), but because the war dragged on for so long, with these armies rampaging back and forth across central Europe literally for decades, the demographic toll was quite substantial. The war’s foremost contemporary historian, Peter Wilson, puts total battlefield deaths at just under 500,000, with disease and malnutrition pushing total military dead up to perhaps 1.8 million. The years of campaigning, with armies foraging and pillaging endlessly, also put horrific stress on rural populations across Central Europe. By one estimate, the rural population in Germany fell by 40%, and the urban populations by 33%, due to broad social disruptions that led to widespread hunger, disease, and flight.

Truly, this was a strange war. It was a genuine continental conflict with titanic consequences which did a great deal to shape both the geopolitical and religious shape of modern Europe as we know it. And yet, few people truly enjoy reading about it, because it was simply a slow burning and complicated mess. A disaster, and not even the entertaining kind.

And yet, amid the general crisis and misery, there were several key advances in the military arts, a few stars rising in the black night, and a few men of great ability flashing their talents for the history books. Among the greatest of these was the King of Sweden, Gustavus Adolphus.

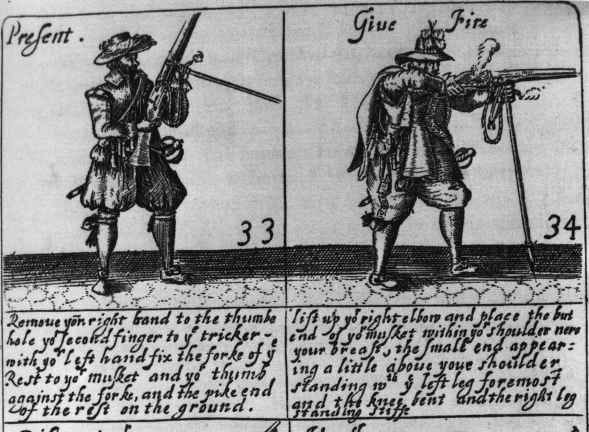

The Thirty Years War was fought during the era of transition from early modern armies, which heavily emphasized pike squares, to more recognizable linear formations of muskets. A Dutch prince named Maurice of Orange was the first to recognize the potential of massed musket fire, if soldiers could be trained and drilled to reload and fire in sequence at a rapid pace. Maurice’s infantry drills (complete with an instruction booklet and handy illustrations) sparked the movement towards the professional musket armies that we recognize from the following centuries, with coordinated and synchronized volleys, standardized weaponry, a combined arms trio of musketeers, cavalry, and field cannon, and the bureaucratization of training and procurement.

During the Thirty Years War, however, this emerging European military system was still in embryo. The many belligerents deployed a variety of different formations, weapons, and military systems, which varied widely in their battlefield efficacy. It was Gustavus Adolphus and the Swedes, however, who fielded one of the most recognizably modern musket armies, and it was precisely this army that won Sweden its brief golden age as one of Europe’s great powers.

Sweden’s involvement in the war came on rather late. It was not until 1630 - a full twelve years into the conflict - that Sweden, coaxed by the ever persuasive French, was cajoled into intervening in the conflict. As a Lutheran, Gustavus Adolphus had clear religious sympathies with the struggling German Protestants, but he also had traditional, earthly reasons for putting his thumb on the scale, aiming to enhance Sweden’s position in Germany for standard purposes of state aggrandizement.

Swedish intervention took the rather bizarre form of Gustavus and his army (a modest force of barely 20,000 men) simply landing on the Baltic coast in Germany and beginning a march south, looking for a fight. The ensuing clash with the Catholic Hapsburgs would happen at a time and place that was largely the result of geographic accident. The Hapsburg army tasked with corralling and defeating the Swedes (under the command of one Johan, Count of Tilly - usually just called Tilly in the histories) took the shortest march route towards Gustavus and his army. It just so happened that the shortest route, in this case, involved a march through Saxony, which had hitherto remained neutral and aloof from the conflict. With the Hapsburgs more or less invading Saxony simply because it was on the way to the Swedish Army, the Saxons were forced into an alliance with Sweden. If Tilly had simply taken the long way around, Saxon neutrality may have held.

In any case, Tilly’s decision to take the direct route and invade a neutral state led to a set piece confrontation when the Catholic Hapsburg force and a Swedish-Saxon coalition army more or less ran into each other near the town of Breitenfeld, just to the northwest of Leipzig. Tilly was about to be on the receiving end of the first demonstration of Gustavus Adolphus’s new look Swedish army.

Breitenfeld is a very peculiar battle when it comes to comparing the field strengths of the armies. In terms of pure accounting, the forces were fairly close in numbers - just under 36,000 Imperial troops against perhaps 39,000 Protestants, with the Protestant coalition more heavily weighted towards cavalry. However, the quality of forces varied wildly across the different arms, and especially within the coalition army.

The Saxon force, which contributed some 16,000 men, or 40% of the total Protestant strength, was overwhelmingly comprised of poorly trained militia or brand new conscripts. Within the Saxon force, 16 of the 22 regiments were either militia or “raw”, meaning they were seeing combat for the first time after minimal training. The Saxon infantry also had perilously few muskets, and were armed primarily with pikes and lighter, older firearms like the arquebus. In contrast, the Swedish army was quite professional and had a very heavy concentration of muskets.

On the other side of the field, the Imperial army was a professional, if aging force. Virtually all of the Hapsburg infantry were professionals, which meant that - despite the Protestants having a slight edge in total numbers - the Imperial force fielded more regular, trained infantry. The crucial question, however, was what function these men were trained for.

The Hapsburg army in 1631 was still organized around units called “Tercios”. These formations had long been the mainstay of Hapsburg armies, especially in Spain and the Netherlands. They were flexible units of between 1,000 and 2,000 men which organized a combined force of pikes and ranged infantry (first crossbowmen, then arquebusiers, then musketeers) into a composite formation. The anchor of the tercio was a mass of pikemen, around whom “sleeves” of musketeers and arquebusiers could be arranged. This gave the tercio fighting flexibility, with a heavy pike mass capable of close combat with the enemy, and ranged “sleeves” that could be brought around to exchange fire. This unit enjoyed great battlefield success for nearly a century, but what the Hapsburg military establishment did not understand was the extent to which muskets had rendered the concept increasingly shaky.

The Tercio suffered two substantial drawbacks after the widespread introduction of muskets. The first, obviously, was that the huge number of pikes and arquebus created a unit with lower ranged firepower density. The second disadvantage was the relatively deep arrangement of the unit (up to twelve rows deep), which necessarily implied that a smaller share of the musketeers could fire at once. In contrast, the Swedish army had by now transitioned to more linear, elongated battalion of musketeers (the type more familiar to us), which meant that the Swedes could offer an equivalent amount of firepower with far fewer men.

All in all, this was a strange sort of battle, with three armies of widely varying quality. An Imperial Catholic army, professional and competent, but fighting in an aging style, against a coalition comprised of an amateurish and poorly armed Saxon force and a cutting edge Swedish army that was armed to the teeth with modern muskets and cannon.

The opening phase of the battle displayed the disparate fighting quality of the belligerent parties. Breitenfeld began, after an exchange of cannon fire, with the Imperial army launching two fairly unimaginative, but ferocious cavalry attacks on the wings. On the left wing, the attack went disastrously, with the Catholics stonewalled by a tough Swedish cavalry wing supported by musket fire. All told, the Imperial cavalry would regroup and launch a grand total of six attacks on the Swedish cavalry, but they were repulsed and worn down each time. In total contrast, the charge on the Imperial right wing smashed right into the Saxon cavalry and routed them from the field entirely.

The situation on the two flanks could not have been more different. The attack on the left was bogged down, but the right wing - manned by the lousy Saxon force - seemed to have been cracked wide open. Tilly made what was, all things considered, the natural decision, and decided to move the mass of his infantry against the Saxons, with the aim of blowing the Protestant flank wide open and rolling up their whole army.

This was a textbook maneuver, and a cursory glance would have supported the move. Tilly was moving his mass to a point of great leverage, hoping to turn the Protestant flank. Who could disapprove of such a maneuver?

There were two problems with Tilly’s flank attack. The first was intrinsic to the formulation of the armies: Sweden’s linear musket units simply had far more firepower than the tercios. By simply rotating to keep their lines of fire oriented towards the Hapsburg infantry, they exposed Tilly’s tercios to devastating musket and cannon fire.

The second problem related to the failed Imperial cavalry attack on the opposite flank. After launching a wave of charges and being repeatedly repulsed with heavy casualties, the Hapsburg cavalry on the left wing had had enough and were driven from the field. This left a powerful Swedish cavalry grouping on the far side of the field with nothing to do. So, they attacked.

Fundamentally, the Imperial Army now had nothing operationally that they could do to salvage the battle. Tilly’s gambit, moving the weight of his force towards the Swedish flank, had come up bust because the Swedes refused to sit statically and allow him to complete his maneuver. Instead, they simply pivoted along with him. Even more importantly, the linear Swedish formations were able to present more concentrated musket fire than the pike-heavy Hapsburg tercios.

Even more pressing than the Swedish muskets, however, were the Swedish cavalry units on the far side of the field who now had total freedom of action after repulsing the Imperial attacks. They now came sweeping across the field into the Imperial rear area. One detachment got all the way behind the main infantry mass and captured the bulk of the Imperial cannon; they then turned these guns on the catholic infantry. Much of Tilly’s army was now caught in a crossfire, taking musket and cannon fire from the Swedish army in front of them while being raked from behind with fire from their own captured artillery.

Caught strung out in a failed lunge for the flank, with the Swedes now in control of literally all the cannon on the battlefield, the disintegration of the Imperial army was now a foregone conclusion.

The crushing of the Imperial army at Breitenfeld had far reaching impacts, and was crucial in prolonging the devastating conflict of the 30 Years’ War. It was, in fact, the first battlefield victory of substance for the Protestant side - and what a victory it was. Tilly’s formidable force of over 35,000 men was entirely crushed. Some 7,000 men were killed, and nearly 10,000 captured - but a significant number also simply dissipated and fled. After the battle, Tilly could reconstitute a cohesive army that numbered less than 8,000 men - far too meager to give battle to the Swedes. This decisively altered the trajectory of the war, reinvigorating the Protestant cause and ensuring further years of bloody attrition.

As for the battle itself, the spectacular destruction of the Imperial force elucidates several principles. In the broadest sense, the problem with Tilly’s conduct of the battle is as follows - simply getting to the enemy flank is not enough if it does not create an asymmetry, either by delivering superior firepower to a decisive point on the field, or by disrupting the enemy’s ability to make decisions. Tilly’s oblique move to the flank accomplished neither of these objectives. The Swedes, by simply pivoting their line towards the Imperial line of movement, retained a firepower superiority, and by moving the bulk of his infantry off their start lines, Tilly exposed his own left flank to a devastating counterattacking.

Breitenfeld may seem, at first glance, to be an odd battle to choose to demonstrate maneuver principles, seeing as how the army that attempted the decisive maneuver was the one that was smashed. In this, however, the battle demonstrates the requisite for maneuver to succeed. In our first entry in this series, we spoke of maneuver as a way to create an asymmetry on the field, by bringing superior fighting power to a decisive point. In this case, however, Tilly’s move to the flank did not achieve this; it was simply an aimless march into Swedish fire. The Imperial formations were not equipped or oriented properly to achieve anything once they had reached the flank, while the Swedish army pivoted expertly around and reversed the logic of the flank attack; before long, it was the Imperial formation that was being torn apart by the physics of the battlefield.

Through his clever counter-maneuver, Gustavus Adolphus demonstrated the emerging geometry of musket armies. The move from dense, square shaped Tercio style formations to the long, thin lines of musketeers employing volley fire created a definitive axis of firepower which was perpendicular to its direction of movement. Musket armies moved in a column formation, but maximized their firepower from a line. Mediating the relationship between vertical movement and horizontal firepower became one of the foundational problems for early modern armies.

At Breitenfeld, the Imperial army was smashed in cinematic fashion because the Swedes kept their axis of maximum firepower directly on Tilly’s forces at all times with an artful and gentle pivot, forcing the Imperials to stand under withering musket and cannon fire right up until the cavalry counterattack delivered the coup de grâce.

The military system deployed by Gustavus Adolphus was immature, but even in its nascent form it showcased the hallmark characteristics of early modern warfare. Like the broader political scheme of the Thirty Years War, the military arts dimly foreshadowed, as if through a foggy window, the great continental wars to come. At Breitenfeld in particular could be seen the devastating impact of massed musket and cannon fire, the shift from dense squares to long lines of infantry, and the synergistic use of cavalry as a weapon of shock, disorientation, and exploitation.

Gustavus Adolphus himself possessed a blend of characteristics both archaic and modernizing, personifying this peculiar proto-modern war. Like great modern commanders, he understood the criticality of combined arms warfare, deploying cannon, musket and cavalry in a synchronous symphony of destruction. He was an ambitious and visionary modernizer that gave form to the emerging Swedish power. And yet he was, in many ways, a very ancient sort of commander, who led from the front and liked to personally lead cavalry charges, as if he was Alexander the Great. At Breitenfeld, he led the decisive cavalry attack from the wing and won a great victory. At the Battle of Lutzen, in 1632, he was shot off his horse and killed. He embraced and lived the totalizing experience of battle, where victory and death constantly and simultaneously loom.

Gustavus burned brightly, but shortly. He fought for only two of the war’s thirty long years, yet is still remembered as one of the dominant personalities, chief defenders of Protestant prerogatives, and greatest military practitioners of the era. The sudden eruption and extinction of the man mirrored Sweden’s larger experience as a great power - emerging in short order as the dominant power on the Baltic Sea, only to be crushed less than a century after Gustavus’s death by the rising power of Peter the Great’s Russia. The candle that burns twice as bright, burns half as long.

How to roll up a flank

Some 170 years separated Gustavus Adolphus, who helped usher in the age of professional European musket armies, and Napoleon Bonaparte, who signified the apogee of this military system. In that intervening period, few commanders earned such enduring fame as Frederick II, King in Prussia - or as we know him, Frederick the Great.

Frederick is something of an archetype for stereotypically German qualities - dutifulness, industriousness, administrative efficiency, rationality, and battlefield aggression. Even after filtering out the idealized man glorified by patriotic German historians, there is no question that Frederick (or “Old Fritz”, as his soldiers called him in his later years) was both a skilled military practitioner and a man that operated within hard, defined limits.

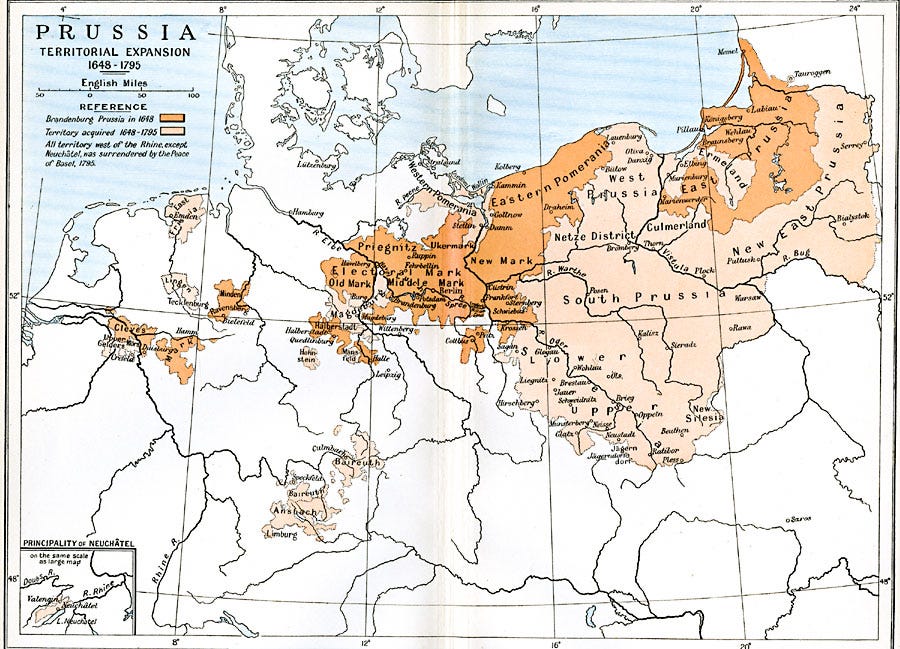

The central event of Frederick’s life was a series of wars fought against what seemed like an overwhelming coalition of enemies, pitting tiny Prussia against the Austrian Hapsburgs, France, and Russia. Given these stacked odds, it is somewhat natural to lump Fredrick into a category with Napoleon or even Hitler, as a sort of “man against the world”, but this would be wrong. Napoleon fought a war for total continental supremacy. Frederick fought a series of wars for Silesia - an industry rich Hapsburg province (in modern day Poland) roughly the size of Slovenia or Israel today. With such modest prizes at stake, to cast Frederick as a would-be world conqueror is a gross misrepresentation.

Furthermore, Frederick’s legacy as a military man was clouded by efforts from the later German General Staff to portray him as the inventor and first practitioner of German “annihilation battle”. This, of course, helped to validate their own doctrines and planning, by positing that they were dutifully following in the footsteps of Prussia’s most famous king. A study of Frederick’s battles, however, calls this interpretation into question.

Frederick, as a king and as a general, was a man who operated rationally within a set of difficult and constraining parameters. Throughout his wars, he found himself on the wrong end of an overwhelming demographic and economic disadvantage, against enemies that could perennially field multiple armies larger than his own. The saving grace - the only thing that even allowed Prussia to attempt to fight such a war - was the geographic dispersal of his enemies around him. Prussia occupied the central position, with enemies arrayed in a broad semicircle around him - France to the west, Austria to the south, and Russia to the east. This prevented the anti-Prussian coalition from coordinating or concentrating their forces, and allowed Frederick to dash around Central Europe, frantically marching from front to front, fighting one enemy army at a time.

Frederick’s wars resembled a back and forth walking tour of Germany, with a battle at the end of each march. The nature of the enemy coalition, however, meant that Frederick faced genuine urgency to take battle. Because there was always another enemy lurking on another front, always another predator to swat away, the Prussians could not afford to dither, marching back and forth in that irritating dance of armies that are hesitant to roll the dice. Instead, Frederick and his generals needed to find the enemy army and immediately attack it, with the intention of mauling it badly enough to send it scurrying back, so the next enemy could be confronted and given the same treatment.

This manifested itself in an extreme degree of battlefield aggression which put battle itself at the center of the campaign, rather than pesky incidentals like logistics and position. Frederick had no time for these things. He only wanted to know where the enemy army was so that he could attack it. Famously, he expressed his art of war in a single sentence: “The Prussian Army always attacks.”

This was not always a recipe for success. Two of Frederick’s early battles, at Prague and Kolin, turned into bloody debacles that cost the Prussians enormous casualties. In both instances, Frederick attempted to march the main mass of his army to the enemy flank, but in both cases they - like the Imperials against the Swedes at Breitenfeld - were unable to fully turn the enemy flanks, and ended up simply hurtling their men at the main enemy fire axis, creating unimaginative carnage. Frederick had an almost instinctive urge to get to the enemy flank, but this was always more difficult than it sounded. Nevertheless, the basic recipe for Frederician warfare was clear - find the enemy army, march to his flank as fast as possible with as much firepower as possible, and then attack immediately. It was only as question of perfecting the implementation.

The Prussians finally achieved the idealized display of this scheme in the December of 1757, at the Battle of Leuthen.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.