In the first entry in this series, we examined what may be termed the absolute fundamentals of maneuver warfare - the concentration of fighting power, penetration into the enemy rear, and the envelopment of some or all of the enemy force. A single envelopment scheme of this sort, whether achieved through an asymmetrical deployment like the Thebans at Leuctra or a flanking movement like Rommel at Gazala, represents a sort of basic, stock model maneuver scheme - a potent, but relatively textbook design.

In this entry, we will expand the scope of our study to look at maneuver on a larger scale, and in so doing demonstrate a countervailing principle to the schwerpunkt that we introduced last time. Schwerpunkt denotes the concentration of massed fighting power to allow maximum effort to be exerted at a decisive point. This is a powerful battlefield tool, but it is not without risks and downside - the accumulation of a concentrated mass, if unveiled by the enemy’s intelligence, will reveal the attacking intention and alert the enemy to vulnerabilities in other positions.

What we are speaking of here is the great benefit of operational ambiguity. All military decisions are intrinsically wrapped up in the basic game of intelligence (learning what your enemy is up to) and counter-intelligence (hiding what you are up to). One of the paradoxes of strategy, therefore, is that actions that may have benefits in the form of battlefield asymmetries - such as concentrating forces - may generate negative asymmetries by communicating one’s intention to the enemy.

Anyone who has played chess (or any strategy game, really) is aware of this paradox. Developing pieces for an attack brings with it the intrinsic possibility of your opponent recognizing your intention and reacting optimally - because he is always afforded the opportunity to react. Therefore, in chess as in war, maintaining some level of ambiguity is absolutely necessary.

One way that this can be achieved is through what we call the dispersion of forces. This is the opposite of schwerpunkt and concentration, and correspondingly it reverses both the positive and negative asymmetries of force concentration. The concentration of forces offers a high level of combat power, but a very low level of strategic ambiguity. Dispersion, in contrast, offers dissipated and weakened combat power, but maximum ambiguity. The difficulty lies in managing the relationship between the two.

Throughout history, some of the most successful commanders have been those that were able to maintain a high degree of force dispersion - spreading units out and maneuvering them in a way that left the enemy paralyzed by ambiguity, only to bring them together at the crucial moment for maximum combat effectiveness. The ideal is for the dispersed army to maneuver independently, but fight together - pivoting seamlessly from dispersion to concentration at the correct moment. This is materially a difficult thing to do, because it requires not only mobility but also an effective command and control system to synergistically move large units across a wide theater, bringing them together for concentrated battle at the optimal time.

Let us examine a few of the preeminent examples from history of this dispersion-concentration duality, and the skillful movement of large units across vast spaces. Unsurprisingly, these examples come from three of history’s preeminent military geniuses, beginning with one of the most iconic men in all of history - the illiterate world conqueror and lord of all who dwell in felt tents.

The Apogee of Genghis Khan

Everybody knows of Genghis Khan. His name continues to carry some of the strongest cachet and instant recognition of any historical figure - though the name itself is something of a point of debate. Probably, it should be spelled and pronounced something closer to “Chinggiz Khan” - a title that meant something like “universal ruler”, which is thought to derive from the Turkic word “Tengiz” which means “sea” - implying that he ruled from sea to sea. But in any case, whether he is Tengiz, Chinggiz, or Genghis Khan, everybody knows him as the ruler of that cinematic Mongol horde that swept across Eurasia, conquering the largest contiguous land empire that the world has ever seen.

Ironically, however, Genghis is most famously known for something that he did not actually achieve in his lifetime - the conquest of China - while his genuine military masterpiece is significantly less famous.

Let us begin with a brief comment on the actual scope of Genghis’s achievements. Before he could conquer the world, he had to conquer Mongolia - a feat that was much harder than it sounds. The Mongol world was one of tribal pastoral nomads - clans eternally wandering the steppe, herding their goats, sheep, camels, cattle, and horses from pasture to stream in seasonal patterns. This was an intrinsically harsh existence which kept the nomads in a permanent state of vigilance - disaster was only one step away. This promoted a deeply myopic political system - that is, focused on the immediate term and immediate needs, with khans constantly under pressure to deliver results and rewards in a steppe society that was constantly in a state of low intensity inter-tribal and inter-clan war.

Taming this politically fluid and unstable steppe - populated not just by the Mongol tribe, but also other peoples like the Niaman, Taichiud, and Khereids who are now mostly forgotten to us, required a long and dedicated program of both military conquest and political intrigue, both of which Genghis Khan (born Temujin) was a master of. It was not until 1206, when Genghis was in his mid-40’s, that he could call himself the undisputed ruler of the Mongol steppe, and take his famous title.

Genghis then spent most of the rest of his life at war, deploying his newly consolidated steppe confederation against a host of foreign states - many of which now seem like passing, meaningless names to gloss over as they go by on the page, like the Xia (a small Chinese state ensconced in the defiles of Outer Mongolia), and the Qara Khitai in western China. While Genghis did subdue these states and break the military back of northern China, the core Chinese states (the Jin and Song Dynasties) were simply too large and too populated to be conquered quickly. Like an elephant eaten one bite at a time, China would not be fully conquered by the Mongols until 1279, more than fifty years after Genghis’s death.

In one of history’s tantalizing twists, Genghis’s greatest military achievement was one that he never planned on at all.

In the early 13th century, much of Central Asia was under the dominion of a polity known to us as the Khwarazmian Empire. This state is frequently identified as a Persian Empire - in that its rulers and military establishment were largely comprised of Persianized Turks. At its Zenith, it was a genuinely colossal and prosperous Islamic state, encompassing most of modern day Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan. This was one of those cobbled together Central Asian Empires, made up of disparate political and cultural pieces - the lingua franca was Persian, the liturgical language of the mosques was Arabic, and the ruling dynasty was Turkic.

Unfortunately, the Khwarazmian Shah committed one of the greatest blunders in human history and brought wrath on a biblical scale down upon his realm.

Genghis had no military intentions in the Khwarazmian realm. He was hard at work eating the great elephant that was China, but he did view the Persian realm as a potentially lucrative trading partner, and dispatched a caravan with envoys to trade in the Khwarazmian markets. Unfortunately, the Shah’s governor in Otrar accused the Mongols of being spies, looted the caravan, and killed many of Genghis’s men. When Genghis sent three ambassadors to the Shah to demand restitution, the Shah had one of them beheaded and sent the others back to Genghis with their heads shaved.

The murder of an envoy acting in the Khan’s name was perceived as a grievous insult to the Khan’s own honor and person, and so there was nothing to be done but to destroy the Khwarazmian Empire entirely. Hell was coming on horseback.

Genghis’s Khwarazmian campaign, though entirely unanticipated and predicated entirely on the surprise Persian crimes against his traders and envoys, would prove to be the great Khan’s seminal military achievement. More importantly for us, it demonstrates Mongol skill in the operational domain, beyond simply their combat effectiveness.

Most people know that the Mongol army was fundamentally a cavalry army which derived a huge combat advantage from the skill of nomadic horse archers. The signature Mongol weapon was the recurve composite bow. Though neighboring civilizations dismissed the steppe nomads as primitives, the composite bow was a complicated and extremely powerful weapon. Made of a mix of layered materials including wood, horn, and animal sinew, and lacquered to protect it from drying, the Mongol bow was both powerful and light enough to use in the saddle. The Mongol horse archer was able to fire his bow with both accuracy and a stable rate of fire while also steering the horse through coordinated maneuvers with his feet. This was the basic weapons system that conquered most of Eurasia. A horse, a bow, and a man that could control them simultaneously

These skills, however, are tactical in nature - they correspond to Mongol combat effectiveness in pitched battle with the enemy. The invasion of the Khwarazmian Empire, in contrast, demonstrates Mongol operational skill - meaning the maneuver of military units across large distances with extreme precision and coordination.

The Mongol lifestyle inculcated a variety of skills that made them extremely skilled at the rigors of long distance campaigning. As nomads, they were accustomed to living on the move and traveling long distances in the saddle, with mobile food supplies in the form of their flocks. More than that, however, the logistics of moving large herds around the steppe - comprised of animals with different water and food requirements - naturally developed impressive skills at coordinating movements and actions in vast spaces. These skills were honed and demonstrated most potently during the Mongol hunt.

Mongols practiced a unique and impressive form of hunting, sometimes called the Nerge or Battue. This was a ring hunt - thousands of men would begin the hunt in a vast circle, up to 80 miles in circumference. Over the course of a full month, they would slowly move towards the center, driving all the game animals in the area inexorably towards the middle, until at the very end all the prey was trapped in a small killing zone. This practice could bag hundreds of animals, but it was logistically very difficult and required skilled coordination and discipline.

All of these skills made the Mongols the transcendent operational practitioners, as would be apparent in 1219 when the war against the treacherous Shah began. Genghis’s army was divided into divisions called Tumens - units of 10,000 men, which were further subdivided into units of 1,000, 100, and 10. The adopted invasion plan would send these Tumens on separated lines of advance across the breadth of the Shah’s realm, before bringing them together for the killing blow - even 800 years later, it remains a nearly perfect example of force dispersion and timely concentration.

Genghis began his masterpiece by immediately deploying a force of 3 tumen (30,000 men) into the Fergana Valley in the winter of 1219, in the eastern reaches of the Persian realm. This caught the Shah and his generals by surprise, as it called into question longstanding assumptions about the empire’s natural defenses. The Khwarazmian realm was shielded from Genghis by a variety of natural defenses, including the apparently impassable Kyzylkum Desert and the Tien Shan Mountains. The Shah assumed that these barriers would slow Genghis’s deployment and allow him to defend the key access points.

Instead, Genghis immediately sent his oldest son, Jochi, and an experienced general named Jebe do make a rapid crossing of the Tien Shan and burst into the Fergana. Their mission was to avoid a pitched battle and instead break as much stuff and burn as many fields as they could, staying out of range and generally infuriating the Persian forces that tried to grapple with them. Meanwhile, Genghis brought his main force across to the northern periphery of the Persian borderlands and besieged the city of Otrar.

At this point, the Mongol army was divided into two main wings - one breaking things in the Fergana Valley, and the other destroying the city of Otrar in the north. These two bodies then subdivided further. The Fergana division split - Jochi took a portion of the army westward towards the Syr Drya River, while Jebe moved south. The main body in the north likewise was divided, with a smaller force under Genghis’s sons Chagatai and Ogedei staying at Otrar to finish the city off, and the main army - under Genghis’s personal command - seemingly disappearing.

The Shah commanded numerically superior forces and had the advantage of fighting on home turf, but Mongol force dispersion across the breadth of his realm created total paralysis. With at least four large Mongol forces now operating independently within his borders, and total ambiguity as to their intentions, the Shah was operationally frozen and could offer nothing but passive resistance from within the walls of his cities. The larger Khwarazmian army became an entirely passive participant in the war, unable to maneuver or take any proactive action whatsoever. The Mongols, though outnumbered, seemed to be everywhere.

Even so, the single largest body of the Mongol army was unaccounted for. Where was Genghis? In March, 1220, he suddenly appeared in the Persian rear, outside the city of Bukhara. The Khan had crossed the un-crossable Kyzylkum desert, hopping from oasis to oasis, riding in a 300 mile arc to take Bukhara completely by surprise.

The end was not long in coming. Bukhara fell swiftly, and the dispersed Mongol forces now rapidly concentrated on the Shah’s capital at Samarkand, where the Persian reserves were assembled. In a climactic finish to the masterpiece, Genghis feigned retreat from the capital’s formidable fortifications and slaughtered the defending army when it came out the gates to pursue.

In the space of less than six months, Genghis completely destroyed an enormous and stable empire with armies that greatly outnumbered his own. All that would remain after the fall of Samarkand was a manhunt to chase down the fleeing Shah, and a leisurely stroll through the remainder of his shattered realm, sacking cities one after another. The military back of the Empire was shattered.

The operational brilliance of Genghis’s campaign against the Shah is difficult to understate. The theater was more 250,000 square miles. From Bukhara to Genghis’s staging area north of Lake Balkhash is nearly 800 miles. Across this vast distance, using nothing more sophisticated than signal flags and couriers, the Mongols coordinated four large military bodies, completely paralyzing the Shah’s armies with their range, mobility, and precision, before converging to deal the killing blow to at the capital.

The technology of the Mongol armies - a recurve bow and the hardy Mongolian horse - are now artifacts of history, but the brilliant display of dispersion, operational ambiguity, and maneuver are timeless, and it is fair to question if they have ever been surpassed. What Genghis demonstrated with this masterful campaign, eternally, is the power of dispersed maneuver to intellectually paralyze the enemy. The Shah’s empire was destroyed without his army ever attempting a single proactive action. This was a bewildering, disorienting, almost otherworldly way to die - no wonder many of Genghis’s enemies believed he had come from hell to punish them.

Napoleon’s Bloodless Masterpiece

Napoleon Bonaparte is widely understood by acclaim to have been one of the greatest military minds in history. But what was it about his system of warfare that was so effective? Was their something systematic - something that could be copied? Or was Napoleon simply blessed with that undefinable and inimitable gift of genius? To be sure, Napoleon was endowed with tremendous gifts – a prodigious memory that bordered on the photographic, quick decision making, and an instinctive, practically preternatural grasp of the battlefield situation. But Napoleon’s success as a military leader was not only due to his own gifts as a battlefield commander, but also thanks to his redesign and restructuring of the French Army. Napoleon not only wielded the army masterfully in action, but he also rebuilt it into a more powerful force on an organizational level. In his case, genius, doctrine, and weapon worked synergistically.

In the earliest phases of the wars of the French Revolution, republican France deployed massive, bloated armies that tended to overwhelm enemies through sheer mass. These were the armies of the levee en-masse – the mobilization of virtually the entire young male population. This overwhelming amount of armed human biomass successfully defended France, but was too large, undisciplined, and unwieldy to be the basis of a permanent military system, and in any case a nation that is perennially mobilized en-masse is unlikely to be socially or economically stable. The silver lining, however, was that such a massive army made changes to the organizational scheme a necessity.

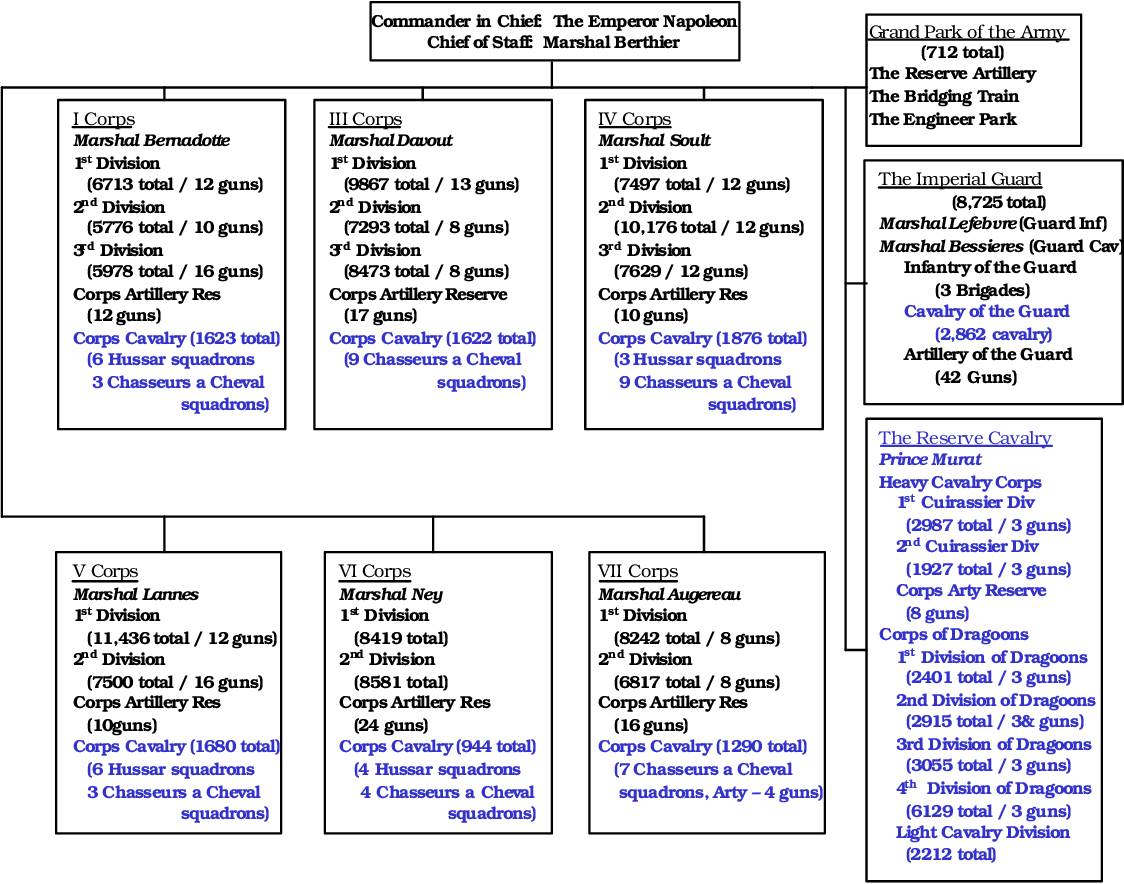

When Napoleon came to power, he undertook an organizational renovation of the army, creating his famed Grand Armee. The central innovation was the organization of the army into units known as corps. The corps was a brilliant organizational development: a force, usually of around 30,000 men, with its own cavalry and artillery components. The size and composition of the corps made it self-sufficient, it could fight on its own if need be, while still being small enough to maneuver at great speed and live off the land. Napoleon’s corps could subsist largely by foraging (really, requisitioning or stealing food from civilians as they passed through) removing the need for cumbersome supply trains, and freeing them to advance quickly ; during a forced march, a corps could cover up to thirty miles a day – a truly impressive speed for such a large formation.

It is difficult to understand how revolutionary the corps was. Before Napoleon, European armies virtually never had standing formations larger than a battalion, and there had never been a systematic combined arms formation before. It is not much of an exaggeration to say that the modern order of battle was invented by Napoleon. In his effort to slim down the bloated revolutionary army, he first conceived of the balanced combined arms maneuver unit - equipped for any battlefield task, large and strong enough to have real heft on the battlefield, but not so large that it could not move at speed and feed itself from the local populations.

In short, Napoleon’s corps were the perfect units for a war of maneuver. They could move quickly and independently through the countryside, and if a single corps encountered the enemy force it was large enough to hold on alone while the other corps converged on the battlefield to rescue it. This ability to disperse large units, maneuver them around the countryside, and then bring them together for the decisive clash was the foundation of Napoleon’s operations - a simple but powerful recipe which has been summarized as “march divided, fight united.”

The corps system of the Grand Armee received its first major field test in 1805, with the eruption of the War of the Third Coalition. An alliance comprised of Britain, Austria, and Russia declared war on Napoleon, aiming to reduce France to her pre-revolutionary borders. Napoleon conceived of a rapid campaign against Austria, to destroy as much of the Austrian army as possible – or even knock Vienna out of the war – before Russian armies could be deployed to Central Europe. This would be the setting for a stunning demonstration of the power and speed of the Grand Armee.

In autumn, 1805, Austria’s objective was primarily to stall for time. Aware of how dangerous Napoleon could be, Austrian commanders were hardly anxious to rush into an unfavorable fight. Their notion rather was simply to prevent Napoleon from penetrating deep into the Hapsburg heartland while they awaited the arrival of their Russian allies. Austrian armies were deployed along several axes that were viewed as likely candidates for a French attack. One such force – an army of over 70,000 men – was anchored on the city of Ulm under the command of General Karl Mack, with the goal of blocking a French advance directly from the west into Bavaria.

Mack believed that the French intended to advance on a direct east-west axis. Napoleon demonstrated an excellent principle in military deception, by showing his enemy what he expected to see. A large cavalry force, supported by a full corps, was dispatched to move conspicuously about to the west of Ulm, dispersing into numerous formations, moving ostentatiously about and literally making as much noise as possible to give the impression of major activity. Mack’s scouts were convinced that a large French army was marching east. This seemingly confirmed Mack’s suspicion that Napoleon was advancing from the west, and supported his decision to cluster his forces around Ulm.

Meanwhile, Napoleon had deployed five corps to the northwest, which were now unleashed to display their potent combination of mobility and fighting power. On September 28, this main French body began a rapid march to the southeast, toward the Danube River to the east of Ulm. By October 8, Napoleon’s 5th corps fought a brief skirmish with Austrian forces at Wirtingen – a city 30 miles to the east of Ulm, in the Austrian rear. Mack now went into a near total operational paralysis, vainly sending probes out in several directions. He was vaguely aware of the fact that he was on the verge of being surrounded, but unable to decide on a potential escape path. The dispersement of the French corps created (you know what I am about to say) ambiguity which left Mack reeling in a loop of confusion.

Napoleon, having marched directly into the Austrian rear, did not fully understand what Mack was doing – largely because Mack was doing nothing. As late as October 13th, Napoleon did not realize that the Austrians remained anchored on the city of Ulm – he expected that they had retreated across the Danube to the south. So certain was he that the Austrians had abandoned Ulm that he ordered Marshal Ney to push through Ulm with his 6th Corps and pursue the Austrians southward. It was only after Ney more or less ran into Mack’s languishing army and was repulsed that Napoleon realized the entire Austrian force remained parked at Ulm.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.