The Last Effort: Germany's Final Battle in the West

The History of Battle: Maneuver, Part 19

In competitive sports, there is a concept which Americans call Garbage Time. The premise is fairly simple - sometimes, a team attains a lead so substantial that it is fundamentally impossible for its opponent to win. A victory is essentially certain, but the rules dictate that the game must continue to be played until time expires (although in some baseball leagues there is a “Mercy Rule” which ends the game prematurely if one team falls behind too far) - this remainder of the game is called garbage time because it is played only as a formality, even though all involved know who is going to win and who is going to lose.

There is no such thing as garbage time when states engage in armed conflict. Certainly, as in sports, wars often reach a point where the ultimate outcome is no longer in doubt, but so long as armies remain in the field all of their strategic and operational decisions matter. On the most intimate level, the outcome of wars remain in doubt until the very end, in the sense that every man fighting still faces the possibility of death. By the autumn of 1944, for example, there was no longer any doubt that Germany faced strategic annihilation - but this was cold comfort to America, British, Canadian, French, or Soviet soldiers, who still faced the very real immanence of their own potential death. Millions of people would die in Europe in 1945, long after the outcome of the war had become a foregone conclusion. Wars are not over until the last shot is fired, and homes, lives, and families face destruction until that moment.

Operational decisions matter a great deal, therefore, both because they have the potential to accelerate or delay the end of the war (thus reducing or increasing casualties) and because they change the geopolitical outcome - particularly in the case of coalition warfare. It was clear, for example, that the allies would win, but the arrangement of that victory was an open question - who would take Berlin? Would the Anglo-Americans invade the Balkans? Who would get custody of coveted German assets, including her many gifted scientists, engineers, technologists, and operational planners? In this context, German strategic decisions mattered a great deal, in that they had the potential to change the particular way that her empire was overrun by the allied coalition.

This makes the closing nine months of World War Two an object of intense intellectual curiosity. Facing annihilation, Germany continued to operate as a strategically intentional entity. The Wehrmacht planned operations, German industry churned out replacement equipment as best as possible and produced monstrously powerful new systems, like the mammoth Tiger II tank, innovative infantry anti-tank weaponry, and the cutting edge ME-262 jet fighter. The Germans conscripted replacements, trained and armed large numbers of increasingly young (and old) soldiers, hung soldiers and civilians alike for cowardice, and generally remained capable of powerful violence and surprising tactical effectiveness right up until the very end. And amid it all, the nervous system of the Wehrmacht - the officer corps - remained in the field, leading a brutal fight to the death.

The Inescapable Clausewitz

Our last entry left the Wehrmacht dangling at the end of a thread, reeling from one of the worst defeats in history. The summer of 1944 had been most unkind to the Germans, with simultaneous operational catastrophes unfolding in sequence. June and July saw Army Group Center in the east being swallowed up by the Red Army’s Operation Bagration, and then August saw another army group thrashed in France at the Falaise Pocket. In an essentially unbroken chain of disaster, the most critical high level formations in both the eastern and western theaters were torn apart in the span of a few months.

What might be surprising, therefore, was that amid conditions that suggested a general collapse, the Germans managed to restore a cohesive front in both theaters. This fact is owed, above all, to the particular talents of one of Germany’s most famous and infamous commanders - Field Marshal Walther Model.

Model is a rather difficult personality to parse, even by the standards of Nazi era German field commanders. Model was brilliant. That much is essentially indisputable. He seemed to be capable of mastering virtually any operational catastrophe, no matter how extreme, and this fact earned him the nickname “the Fuhrer’s Firefighter.” His prowess as a defensive expert who could fix gaping operational problems seems a bit overblown at times, but for our purposes consider that in the aftermath of Germany’s three great operational cataclysms in 1944 - the winter collapse in Soviet Ukraine, Bagration, and the Falaise Pocket - it was Model who was rushed in to take charge in all three cases. After Bagration, he managed to stop the Soviet offensive with a timely counteroffensive in front of Warsaw (a topic for our next piece), after which he was almost immediately flown to the west to salvage the situation in France. It’s not an exaggeration to say that in 1944, you could tell where the Wehrmacht was hurting the most by checking where Model was. Like a firefighter or a trauma surgeon, he had a gift for staving off disaster.

Model was brilliant indeed. But that made his larger character even more confusing, because he was also a true believing Nazi - and not just in the sense of checking boxes and giving the necessary platitudes. He genuinely believed in Hitler and his historical mission, and even late in the war he spoke with absolute confidence of Germany’s inevitable victory. Every bit of evidence that we have suggests that Model truly believed, deep down, that Hitler was a strategic genius, that the fighting qualities of the German soldier could transcend material factors, and that Germany would win the war. These beliefs firmly entered the realm of delusion, and this makes Model rather, shall we say, weird. It is difficult to understand how someone so gifted, talented, so obviously intelligent could also range into overtly cultish territory. Many of Germany’s other great talents would grumble that Hitler had lost the plot, push back, complain, or defy. To the point, most of Germany’s greatest operators were forced into retirement for being too argumentative. Virtually all of the most famous commanders - Rommel, Guderian, Manstein, Bock, Hoepner, Hoth - were fired (or even executed) before the war ended. Not Model. Uniquely along Germany’s talents, he believed and pushed his subordinates to fight fanatically to the end.

One motif of Model’s command was a fairly regular stream of missives exhorting his men to fight, invoking German superiority, the perils of Bolshevism, and their inevitable victory under Hitler’s leadership. One such order proclaimed that “No soldier in the world may be better than we, the soldiers of our Führer, Adolf Hitler!” We can accuse Model of lying here, but as the great philosopher George Costanza reminds us, “It’s not a lie if you believe it.”

Model’s exceptionally strong relationship with Hitler had two tangible operational implications which became a matter of life and death for hundreds of thousands of men.

First, it meant that Model was generally quite good at getting priority access to replacements and material, both because he had Hitler’s ear and approval and because Model had learned early on that it was wise to massively over-ask. Model made it a habit to demand outrageous - nay, impossible, reinforcements, knowing that this could cajole high command into at least allocating something. Demand a dozen additional Panzer Divisions, and maybe you’ll get 2. Ask for 800 tanks, and Hitler might give you 100. In the grand scheme of things, it sounds silly, but it became crucially important that Model’s command generally enjoyed privileged access to reserves and equipment and were thus, by extension, often in better shape than the allies expected them to be.

Secondly, because Model was such a trusted subordinate, he was able to get away with things that other commanders could not - like retreating. Model was certainly capable of standing in place and fighting to the death when he felt like it, and this gave him some leeway to withdraw and give ground without being punished by Hitler. Probably, Hitler had some sense that if Model felt that it was necessary to pull back then there must have been a very good reason indeed. In any case, Model could operate with some level of impunity in a way that few others could.

Therefore, it genuinely mattered that Model was the man tagged to salvage the operational situation in France after the disaster at Falaise.

When Model arrived, the situation map might as well have been a flaming trash barrel. The tattered remnants of “Army Group B” were straggling out of western France towards Paris and the Seine, vaguely wandering towards a rendezvous with German 19th Army, which was retreating from southern France in the wake of an allied landing on the Mediterranean Coast. Probably the best look at the generally ragged state of the German force in France was an October 15th report from German High Command West which determined that the 41 infantry and 10 mechanized divisions in France had at most the combat power of a mere 27 infantry and 6.5 Panzer Divisions - a meager force to hold back the allied wave that was preparing break upon them.

Few would have judged allied command for feeling borderline euphoric. But it was at this juncture, as the mighty allied force rolled eastward out of Normandy towards Paris, the German border, and Berlin, that a dead hand reached from the grave to dampen their joy.

Carl von Clausewitz is perhaps the single most quoted and referenced writer on what we may call the philosophy of military operations, to the point where mentioning him is practically cliche. One of his critical concepts was the idea of friction and culmination - that attacking forces wear down over time and eventually have to stop. In Clausewitz’s own day (the Napoleonic era) this in practice meant that horses and marching men got tired, fodder and powder ran low, wagon wheels broke, and armies generally became more disoriented and had a harder time navigating as they got farther from their bases of support. Furthermore, by definition the attacking army continued to move farther and farther from home, while the defending army got closer and closer, shifting the balance of fighting power in the defense’s favor as time went on. The “culmination point”, as Clausewitz called it, referred to the moment when the attacking force simply could not go any farther, and the attack subsided like the ocean at high tide. In a framework analogous to physics, we might say that attacking requires an energy expenditure which eventually subsides due to friction and resistance in the environment.

Clausewitz wrote his famous book, On War, before anyone had dreamed of trains or trucks or tanks or aircraft. For this reason, we must praise him, because his concept of friction and the culmination point long outlasted the technology of his era, and proved to be an enduring military reality - he had tapped into something genuinely true. And although Clausewitz had been dead for nearly 170 years, his damnable culmination point arose from the mist and confounded the all-conquering Anglo-Americans.

The allied force fanning out into France was genuinely astonishing. In a relatively short period of time it would expand to seven field armies, four of which were American, with a fifth (the French 1st Army) being equipped and supplied entirely by the Americans as well. This vast and seemingly all-powerful host had an astonishing level of material and fuel consumption, and unfortunately for the allies there was a rather limited logistical capacity. The allies had captured several potentially valuable ports, like Cherbourg and Calais, but the Germans successfully demolished the shipping infrastructure, to the effect that by September the allies were still relying on their improvised harbors on the Normandy beaches to supply their great advance.

In essence, the allies had won one of history’s greatest operational victories in France and created a similarly colossal logistical mess. There were two problems - both how to land the supplies and then how to transport them overland. The only way to supply such enormous armies reliably was by rail, but the French rail network was trashed precisely because the allies had bombed it thoroughly to prevent the Germans from deploying and supplying forces to Normandy. It presents an interesting operational problem - when the enemy’s supply system of today is your own supply system of tomorrow, what do you do?

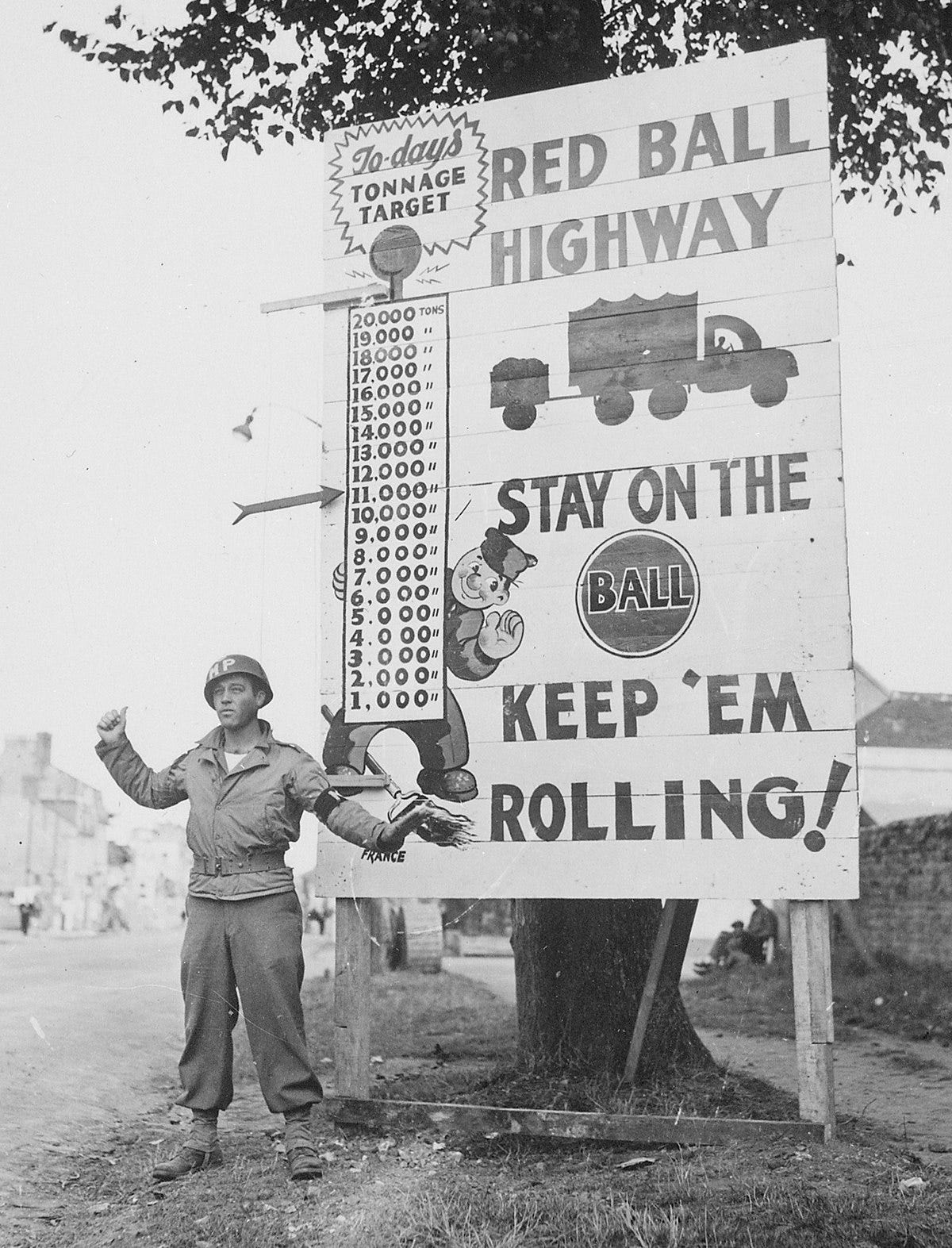

The allies tried to instead lean on their prodigious truck lift. To be very fair, the American truck transport capacity in 1944 was genuinely astonishing - more than enough to drive the Germans green with envy. But it simply was not enough. The famous “Red Ball Express” - an improvised American truck convoy system - managed to move a little over 12,000 tons of supplies per day. This was an astonishing number for a purely truck based system. But by comparison, the port and rail net at Antwerp (in Belgium) could move some 40,000 tons per day. This represents a reality of engineering. No matter how hard one tries or how competent the organization, a trucking network simply pales in comparison to a large port and a working rail network, which the allies did not have. It is a credit to the American trucking system that it managed to sustain the allied advance for any meaningful length of time at all, but it could not work miracles and the advance eventually began to grind to a halt.

The slowing of the allied advance gave Model just enough breathing room to once again perform an apparent work of magic and create a cohesive front out of a routed army. The task required a litany of narrow escapes, half solutions, delaying actions, and improvisations. Model had to withdraw his battered high level units (7th Army and 5th Panzer Army) from France, evacuate elements of the 15th Army by sea from various Belgian peninsulas and islands, contrive a way to insert the new 1st Fallschirmjäger (airborne) division into the line, and try to scrape together a variety of shattered units which were now streaming eastward out of France in a chaotic rout.

Some of the measures that Model had to resort to were rather shocking for this once proud army. Hastily assembled battlegroups were thrown at critical bridges and roadblocks to harass and delay the allied advance, small counterattacks were launched by tiny handfuls of panzers, and retreating personnel were ordered not to waste time looking for their own units but report to the first command post they could find. And crucially - because he was Model - reinforcements were on the way. Two veteran panzergrenadier divisions were en-route from Italy, and the first four of the brand new “Volksgrenadier” divisions were assigned to Model’s command.

The Volksgrenadier formations were rather emblematic of late war Germany’s predicament. Not to be confused with the Volksturm (untrained militia good only for dying), the Volksgrenadier were regular army formations with standardized weaponry and training, but organized far differently from the idealized early war infantry division. They drew their personnel from a variety of disparate sources, like “jobless” Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe staff (since these arms still had bloated manpower despite very few operative ships and aircraft), administrative personnel, and the straggling survivors of destroyed eastern front units. Instead of the typical nine infantry battalions in a standard infantry division, a Volksgrenadier division had six, and instead of a motorized component they were largely equipped with bicycles for transportation (this is not a joke). Most importantly, they were light on heavy weapons but liberally equipped with submachine guns and man portable antitank weapons, like the vicious panzerfaust.

Needless to say, astride their bicycles and with very little artillery, the Volksgrenadier divisions were completely unsuitable for offensive action, but they were surprisingly combat effective in close-quarters defense, and this made them wonderful units for Germany’s purposes, since this was no longer an army fighting to win a war but only to make its defeat as painful as possible for the enemy.

Narrowly extracting his forces from France, inserting precious reinforcements into the line, and reassembling shattered units on an ad-hoc basis - by the end of August, Model had recreated a continuous front across northern Belgium, and crucially had managed to hold the islands and peninsulas northwest of Antwerp, which ensured that the allies could not use the port despite capturing it on September 4th. General Omar Bradley described Model’s resurrection of the German position the following way:

In one of the enemy’s more resourceful displays of generalship, Model stemmed the rout of the Wehrmacht. He quieted the panic and reorganized the demoralized German forces into effective battle groups. From Antwerp to Épinal, 260 miles south, Model had miraculously grafted a new backbone on the German Army.

Model’s stoic nerves and deft touch reassembling his line always draw high marks from the peculiar military historian caste, but we should not overemphasize or romanticize the Werhmacht’s strength. This was a self-cannibalizing force reeling from a sequence of catastrophic defeats, building its line through self-destructive expedients, like using specialized airborne assets (the Fallschirmjäger) as line infantry, pulling resources from other fronts, and assembling ad-hoc battlegroups and Volskgrenadier formations.

Nevertheless, this was sufficient to greatly frustrate the allied camp. They had won a tremendous victory, driving the Wehrmacht from France and shattering its strength at Falaise, but they now faced the limits of their logistical network (the relevant chapter in Bradley’s memoir is simply titled “Famine in Supply”) and - crucially - the realization that they were losing the opportunity to translate their operational victory in France into a total strategic victory; in other words, Model had denied them the chance to exploit the rout in France by getting into Germany proper and winning the war outright.

It was this realization, that the war would likely not be won in 1944, that prompted British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery to draft one of the most ambitious and heavily scrutinized allied operations of the war. One last chance to end the war by Christmas.

The Bridge at Arnhem

Operation Market-Garden was a plan conceived in frustration. The allies had achieved a great feat of arms by shattering the German position in France over the summer months, but the seemingly miraculous reconstitution of the Wehrmacht under Model’s command, along with the ongoing supply headaches stemming from the lack of an operative port, indicated that there was a lot more fighting ahead. This was dispiriting and irksome to the allies, who had felt (rightly) that only a few weeks previously the Germans were on the run. The sense now was that the reward for the victories of the summer was only a brutal winter campaign in a war that now seemed unlikely to end soon. Bradley later wrote that “Montgomery winced as we did over the sudden reappearance of German opposition on his front” - but Montgomery was doing more than just wincing.

In the first weeks of September, Montgomery drafted (and Eisenhower approved) Operation Market Garden. As is often the case, Market-Garden was simple in concept and dreadfully complicated in execution. The premise was cozy enough - the war could be won in 1944, it was thought, if the allies could get their mechanized forces over the Rhine River and into Germany. Therefore, Montgomery proposed to thrust the British 2nd Army northeast through the Netherlands to cross the branches of the lower Rhine (what the Dutch call the Nederrijn) at Arnhem - from there they would roll down into the German plain and have no terrain features of note between them and the German heartland.

The problem with this seemingly simple plan (drive to the river and cross it) was the peculiar geographic nature of the Netherlands, with its low lying wetlands and woods which are entirely unsuitable for armored operations. The terrain meant that the British advance would be confined largely to the main highway from Eindhoven to Arnhem (what is today the A50 highway, but in 1944 was called Highway 69) - creating a long, thin advance vulnerable to counterattack. The second problem was that this path of advance crossed no less than five significant rivers and canals. If the Germans managed to detonate any one of these bridges, the operation was kaput. Thus, a two part operation was necessary - the armored thrust up the highway to the Arnhem bridge (Operation Garden) and a series of paratrooper drops to prevent the Germans from blowing the bridges (Operation Market).

The mountain of postwar literature on Market-Garden tends to criticize the complexity of the plan. For the operation to succeed, the airborne forces had to secure all five bridges - even losing one would scuttle the whole thing. Furthermore, a shortage of air transportation meant that the drops would have to take place in waves, rather than all at once. As for the ground advance, it does not take a genius to understand that trying to push multiple armored brigades up a single highway is a tricky proposition. All things considered, Market-Garden was an operation that really had no margin of error. Everything had to go right - five bridges on one road - for it to succeed.

These were all real problems, but they rather miss the point. The allies wanted to end the war in 1944 for very obvious reasons, and the only way to do that was to get sizeable armored forces over the Rhine, and the only way to do that was to drive to Arnhem and cross the river, and the only way to do that was to push up the highway and secure the whole series of bridges along the way. Add it all up, and you get Market-Garden or something very much like it. If you wanted to end the war by Christmas, this was the play. So, the allies played it.

The problem with Market-Garden was not so much the complexity of the plan, but the fact that there were German forces who worked to foil it. Contrary to the common trope that Montgomery was surprised by the presence of Germans in the operations zone, he knew full well that they were there but believed that they would be largely combat ineffective units due to the mauling they’d received in France. In fact, one contemporary allied assessment concluded that, though Market-Garden was a risk, German forces were assessed to be so weak and disoriented that it would be negligent not to try it.

In fact, there were several operations-capable German entities of note at Arnhem, directly in the path of Montgomery’s planned advance. One was an entire SS Panzer Corps, with its two panzer divisions: 9th SS Panzer was stationed only a few miles to the northwest of Arnhem, and the 10th was loitering a few miles to the south. Just as notable was the presence of Model himself, who had located his headquarters in a small town just to the west of the Arnhem bridge. Thus the most critical aspect of the whole operation - the air drop to seize the Arnhem bridge over the Lower Rhine - happened to land almost directly on top of Model and a pair of Panzer Divisions. In other words, the critical objective of the operation was occupied by nothing less than Germany’s best defensive operator and a pair of the Wehrmacht’s best tactical units.

The critical task of capturing the main road bridge in Arnhem fell to the British 1st Airborne division, and so it was this unit that received the dubious honor of dropping over Model’s headquarters when the operation was launched on September 17. Market Garden was essentially doomed the moment the airborne troops hit the ground - within an hour, Model had organized battlegroups that established blocking positions and hemmed much of the 1st Airborne into a few small pockets. A battalion or so worth of men did manage to reach the all-important bridge, but they lacked the combat power to capture it and remained trapped on the north bank of the river, exchanging gunfire with the Germans on the other side of the bridge. By the end of the day, 1st Airborne was trapped in a pair of pockets - one around their original landing zone, and the smaller one around the north end of the Arnhem bridge - and could do nothing except dig in and wait for the ground forces to link up with them.

Unfortunately, the ground advance was having all manner of difficulty building up steam. The problem, once again, was unexpected German combat potential. The first stage of the assault, around Eindhoven, drove directly in between a pair of German units - 59th Infantry Division to the west, and 107th Panzer brigade, equipped with Panther tanks, to the east. Meanwhile, the road itself was clogged up with doggedly defended German roadblocks.

Because Operation Market Garden had called for only a single axis of advance, the British ground forces had no prospect for outflanking or avoiding these German defenses, and were obliged to slog their way up the road while fighting off counterattacks from either side. In fact, the terrain made any notion of fighting off-road almost impossible. The commander of the ground forces, General Brian Horrocks, flatly insisted that “The country was wooded and rather marshy, which made any outflanking operation impossible.” It was the highway or bust.

With the ground advance behind schedule, the decision was made to proceed with a reinforcement of the airborne forces by dropping in the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade to back up the British paratroopers around Arnhem. Unfortunately, the Poles landed on the south side of the Neder Rhine (the British were still stuck on the north bank) and were soon trapped against the river as well.

The whole thing ended rather quickly. With ground forces stuck in a slow and painful slog up the road, the allied paratroops at Arnhem were fundamentally doomed. The SS Panzer divisions around Arnhem wheeled in to crush the immobilized allied airborne forces, and it was all over by September 27. The Wehrmacht still held the Arnhem bridge.

Operation Market Garden is a much autopsied episode in the war - a fact that is perhaps odd, given how small it was. Total Allied casualties were a little over 16,000, with the Germans losing some 7,000 men at most. The worst of the damage by far fell on the poor British 1st Airborne, which took 1,500 killed and 6,500 captured (wiping out two-thirds of the 12,000 man unit). Still, in a war that was burning through divisions of all nationalities like cheap kindling, this wasn’t a particularly grand or horrific battle.

The implication of Market-Garden’s failure, however, was massive. It marked the end of an open and highly mobile phase of the war in the west and largely froze up the front for the following three months. The opportunity to exploit the rout in France had vanished, and the Wehrmacht once again manned a continuous front barring the path into Germany. The war would not end in 1944, and there would be no end-run over the top of the Rhine into Germany.

Part of the endless fascination with Market Garden stems, to be sure, from the nagging American dislike of Montgomery, which leads to something bordering on an ill-placed schadenfreude at “Monty’s” failure. Naturally, American patriots did not extend the criticism to Eisenhower, who signed off on Market Garden with full agreement. Of course, on the other side, the British tend to be highly defensive of Market-Garden (and Montgomery by extension), and both Churchill and Montgomery argued that the operation was “90% successful” in that it liberated a swathe of Dutch territory. In any case, all manner of finger pointing ensued, with some Americans blaming Montgomery, Eisenhower blaming the weather, and Montgomery blaming both a “lack of support” and the Polish paratroopers, whom he accused of performing poorly.

They all should have blamed the Wehrmacht, and Model in particular. Operation Market Garden would have been a perfectly viable operation if the Germans had been in a state of disarray and general combat ineffectiveness, as they indeed had been as recently as the end of August. Model demonstrated - as if this war had not provided more than enough proof already - that modern armies have absolutely astonishing recuperative powers, so long as the command apparatus remains intact and the men in the field feel that the war is still worth fighting. In Holland, in 1944, Model’s personal presence was significant, both through his skill in returning order and cohesion to his forces, and in his privileged access to replacements and equipment. In the case of Market Garden, a mere two weeks was sufficient for the Germans to sort themselves out and defeat Montgomery’s audacious push for the Rhine.

The Germans had suffered two extraordinary defeats, in Soviet Belarus and in Normandy, which by all accounting ought to have pushed them past the breaking point and yet here they were, still fighting hard with a continuous front in both theaters - in both cases thanks in large part to Model’s fanatical and competent handling of the operations map. The Germans could not win the war, of course, but the force regeneration powers of the Wehrmacht remained prodigious, German men of increasingly disparate ages still believed that the Reich was worth fighting and dying for, and no single defeat - no matter how catastrophic - was sufficient to knock the Germans out of the field. And so, with the front congealing into a solid wall, the summer maneuver period gave way to something far more primitive and horrible.

The Things Their Fathers Saw

With the end of Market Garden and the failure of the allies to fully clear the river lines in a continuation of the summer campaigning season, the western front coagulated into a continuous arc of wall to wall armies, lined up across from each other all the way from the English Channel to the Swiss border. The German line - understrength and overmatched, but still continuous and cohesive - ran from the channel coast just north of Antwerp (where littoral positions still allowed the Wehrmacht to block allied access to the port) due east towards Arnhem and the Rhine; from there it curled southward towards Switzerland passed through the Ardennes, the Moselle Valley, and the so-called Burgundian Gap, in a course that roughly corresponded to the prewar western borders of the Reich.

Overall, this front was nearly 600 miles long, and given the parlous state of German manpower it was hardly a simple matter to man it properly. Crucially, however, the allies were still struggling with endemic fuel shortages (and would continue to do so until Antwerp was unblocked) which forced them to undertake limited offensive actions - in effect, attacking the entire German line frontally all across the board in a firepower-intensive grind.

Wall to wall armies from the channel to the Alps, limited mobility, and fires-intensive frontal assaults across a broad front. If it sounds familiar, that’s because it is - and for the last three months of 1944, the Germans and the Allies would fight an attritional-positional battle reminiscent of the First World War: a gruesome homage to the war their fathers fought.

In theory, much of the German defense was now anchored on the infamous “Siegfried Line”, or the “West Wall” - a dense nest of German defenses erected in a sort of mirror image to France’s prewar Maginot Line. On paper, fighting on a prepared defensive line ought to have accrued significant advantages for the Wehrmacht, and indeed German propaganda relentlessly trumpeted the idea of the Reich’s impenetrable western border, defended as it was by both the West Wall and the Rhine.

However, notwithstanding the obvious anachronism of an “impenetrable defensive line”, and even ignoring the obviously stark warning from Germany’s own experience in 1918, when they had lost the war despite having both the Hindenburg Line and the Rhine to defend behind, it turned out that the mighty West Wall was not all it was cracked up to be. In particular, the West Wall had several specific defects:

Much of the original line had been built in 1938 and 1939, designed to withstand the ordnance of the day - consequentially, many of the emplacements were simply not built to survive the much more powerful weaponry in use by 1944.

Many of the West Wall’s heavy weapons (particularly artillery) and equipment (like radios) had been stripped down throughout the war for use elsewhere, and in particular to equip the Atlantic Wall in France.

An emergency construction program designed to get the wall back into fighting shape was entrusted to domestic Nazi party officials (Gauleiter) and civilian construction crews who had no real understanding of military engineering; consequentially, the new portions of the line tended to be haphazard tangles of bunkers, pillboxes, trenches, barbed wire, and tank obstacles which were not arranged in a systematic way - for example, there was relatively little thought given to lines of sight or fields of fire.

Thus, despite the ostensible impregnability of the West Wall, German troops found a disappointing mixture of sloppily built new fortifications and outdated prewar bunkers that would be pulverized by modern allied munitions - and underlying it all, an endemic shortage of heavy weapons, communications equipment, ammunition, mines, and men. Probably the best thing that can be said for the West Wall is that it did at least have plenty of obstacles to complicate the allied assault, and the presence of the belt helped give confidence to inexperienced Volksgrenadier units who did not know any better - green troops always feel and fight better in fixed defenses. But certainly, no German soldier with even a modicum of realism believed that they could hold the line in the west indefinitely.

In the short term, however, a lack of allied fuel and logistical capacity - combined with Eisenhower’s decision to keep up the pressure across the entire front - meant that there was nothing to be done for the allies except to attack the German position head on. This became an ignominious and inglorious period of the war - the allies continued to churn their legs and grind forward, but their advance was slow and characterized by general carnage.

The allies would launch a series of limited offensives - virtually unremembered today - which generated enormous casualties on both sides as they bashed their way through static German defenses. General Bradley would orchestrate Operation Queen - intended to drive over the Ruhr River up to the Rhine to establish a launching pad for a future offensive into Germany proper, but the assault devolved into an agonizingly slow and bloody fight, with the Germans defending effectively in the dense confines of the Hürtgen Forest. Operation Queen failed to reach the Rhine - in fact, it did not even cross the Rhur - and cost US 1st and 9th Armies some 40,000 casualties.

Meanwhile, farther to the south, General Patton’ 3rd Army had a damnably difficult slog trying to clear the Germans out of the Loraine Region. In particular, the Germans put up a fierce resistance at the fortress complex around Metz, and Patton’s attack - which began on September 27 - could not clear out the last pockets of resistance until December 13.

The Lorraine Campaign became a topic of notoriety and great criticism against Patton (though today most people have never heard of it). Like the rest of the allied operations in the autumn of 1944, Patton’s assault towards Metz was nothing more than a frontal assault which generated huge casualties, with the American advance greatly complicated by both incessant rain and logistical difficulties. Patton became somewhat obsessed with Metz, which he grandly (and incorrectly) proclaimed had not been captured in centuries. However, Patton the cavalryman was completely out of his element in a grinding positional slog, and really did very little to direct the battle - he communicated only infrequently with his subordinates, rarely intervened in battle management, and generally spent most of his time griping at his command post and in his diary. He speculated that his army was being deliberately starved of fuel as a sop to Montgomery, and that the supply difficulties were somehow being manufactured to influence the presidential election back home in the USA. Meanwhile, he wrote to his wife asking her to send him Pepto-Bismol - what he called “pink medicin” - claiming that the rain and the slogging attack were giving him an excess of bile.

By any measure, the Loraine Campaign was not Patton’s finest moment. He was essentially missing in action, exerting little control over the operation, preferring to gripe and pout in his headquarters. Meanwhile, his Third Army created a meatgrinder in its assault, suffering 55,000 casualties in addition to some 42,000 “nonbattle” casualties - frostbite, sickness, trench foot, and the like. The latter in particular had become an epidemic among American troops, who found that the army regulation footwear was simply inadequate for cold or wet weather. The American quartermaster in Europe, General Robert Littlejohn, admitted that in snow the standard issue boots were “nothing but a sponge tied around the soldier’s foot.” But boots or no boots, the attack went on. When Bradley urged Patton to break off the attack on Metz - “For God’s sake, lay off it”, he said, “You are taking too many casualties for what you are accomplishing” - Patton ignored him and railed about Bradley’s timidity in his diary.

But Bradley had a point - Lorraine was remarkably costly to Patton’s Army. According to a 1985 US Army study of the campaign (which emphasized Patton’s indifference to overstraining his logistics) fully a third of all the casualties suffered by Patton’s 3rd Army in the entire war were incurred in Lorraine during only a three month period. Probably the most poignant summary of the autumn fighting came from a war reporter embedded with Patton’s 5th Infantry Division, which took tremendous losses reducing one of the Metz forts. He wrote, simply: “We were attempting to assault a medieval fortress in a medieval manner.” But perhaps we are being too hard on Patton - Bradley’s Operation Queen fared no better, nor were the British going anywhere fast up in the Netherlands.

It was by any reckoning a miserable autumn, one which has been largely forgotten in the historiography simply because it seems to be such an aberration - an archaic throwback to the last war. Instead of sweeping mechanized operations, the war had devolved into ugly frontal assaults that burned through entire infantry battalions to advance 200 yards through the forest and the mud. Losses were severe enough that American units became chronically understrength, and casualties routinely outstripped replacements. Patton, in an effort to keep his frontline units as strong as possible, began rounding up rear area personnel - clerks, administrative personnel, drivers, and so forth - to be added to his rifle units after a cursory infantry training. By December, fully 10% of Patton’s rear area personnel had been thus “drafted” into the infantry. We are of course used to the idea that the Germans had to increasingly resort to emergency stopgap measures to fight the war, but the idea that the powerful American Army would have to do likewise is more troubling.

Of course, the brutal and firepower-intensive frontal allied advance generated plenty of German casualties as well, and the Wehrmacht indeed frequently got the worst of it due to their lack of artillery and other heavy weapons. In the long arc, this sort of casualty trading remained a terrible game for the Wehrmacht, but that did not make it any more pleasant for the Anglo-Americans, who were universally frustrated with the slow pace and exorbitant cost of this phase of the war. Bradley would at one point confide that he now feared that the Germans could continue fighting “bitter delaying actions” until 1946. Few could doubt that the allies were winning, but victory seemed to be much farther off and much more costly in lives than they had reckoned.

But the Wehrmacht was not particularly interested in delaying actions. The entire arrangement of the war had become abhorrent to them, with the allies holding all the initiative and slowly grinding the Germans to dust. This was no way for a German army to die - it ought to die as it lived, which is to say attacking, moving, operating - not fighting a reactive defense out of static positions. The Wehrmacht was not a rodent, to die cowering in a burrow, but a wolf that lived and died by the hunt. It was time for the last hunt.

Watch on the Rhine

The Germans had been looking for an opportunity to counterattack almost from the first moment that the battle began to go wrong for them in Normandy, and they never really stopped. No sooner had Bradley breached the German line with Operation Cobra than the Wehrmacht jumped to put together an ill-fated counterattack (Operation Luttich) which led directly to the catastrophic firebag at Falaise. Undeterred by this debacle, the Wehrmacht continued to seek opportunities to regain the initiative, but found this to be very difficult given the pace of the American explosion into France. A plan to have 5th Panzer Army counterattack from the Dijon area (southeast of Paris) proved futile when Patton overran the staging area in a fury, and by late August it was clear that no proactive occupations could be launched in the near term, given the state of the German forces fleeing from France. Indeed, it was all Model could do to get them sorted out into a coherent front, as we have seen.

Given the beating the Wehrmacht had taken in France, it is perhaps surprising that they even dreamed of attacking, but Hitler and the OKW (Wehrmacht High Command) talked themselves into an optimist scenario in which the Germans would have a strategic window during the winter to go on the offensive. Specifically, a winter offensive was viewed as not only possible but even advantageous for four reasons:

Poor winter weather could be expected to intermittently ground allied aircraft, neutralizing the enemy’s advantage in the air.

Allied logistics were (correctly) viewed as inadequate and fragile, such that allied frontline units were expected to be poorly supplied in the winter.

Winter mud and snow were expected to further strain allied truck-borne logistics and the mobility of allied reserves.

Finally, the interim period from October to December could be used to outfit a mechanized strike force with new equipment.

The general impression was that the winter months would present an opportunity to unleash a powerful new mechanized package, complete with brand new Panzer Divisions, against an allied army with overstretched logistics and an air force grounded by blizzardous conditions. All in all, this was an overly rosy assessment which required all manner of optimistic assumptions, but for a German army that was preternaturally conditioned to attack, it represented the only remotely reasonable hope. And so, the decision was predestined: the Germans would attack in the winter.

But where? And with what objective? These questions fell to the OKW planning staff.

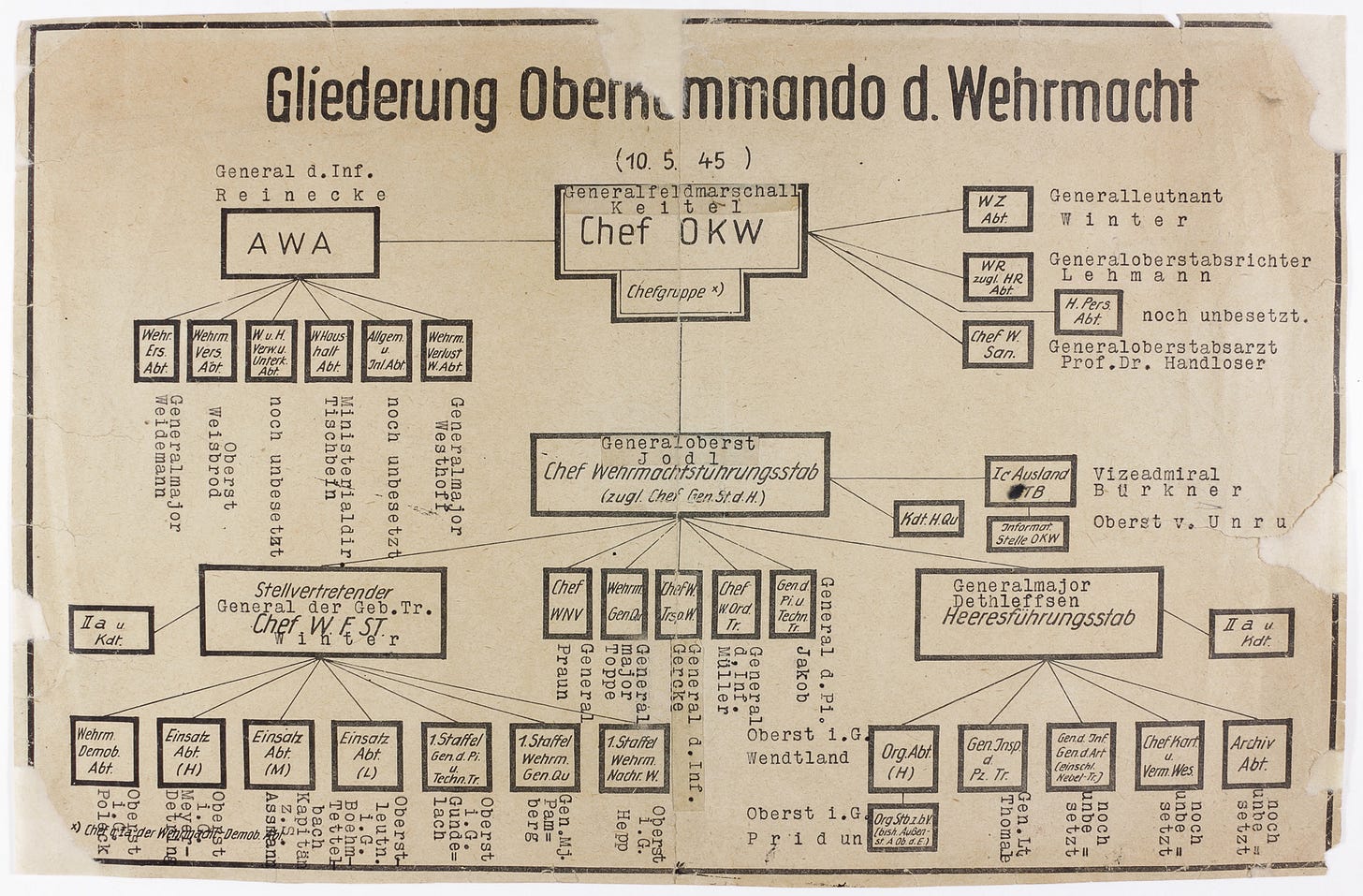

Remarkably, despite nearly a full six years of war for Germany, by the autumn of 1944 the OKW had never planned a major operation. Here, we dovetail into the troublesome German organizational chart. Nazi Germany had two major military planning bodies: the OKW (Wehrmacht High Command), and the OKH (Army High Command). In theory, the OKH was subordinate to the OKW, with the Wehrmacht Command acting something like a Joint Chiefs of Staff. However, due to Hitler’s own unique management style, a decision had been made years prior to instead divide operational jurisdiction, such that the Army (OKH) ran the war in the east against the Red Army, while all the remaining theaters (air defense, naval operations, the Mediterranean and North Africa, France, and so forth) were run by the OKW. In a more simplified sense, the Soviets fought German forces under the OKH, while the Anglo-Americans fought in the OKW’s theaters.

The level of disharmony is notable. While the allies managed to coordinate military operations at the international level, with Britain, the United States, and Commonwealth forces operating in the field together and the USSR kept closely in the loop, Germany in effect fought two separate wars, with separate high commands managing the various theaters. Remarkably, Hitler himself was the only real point of coordination between the OKW and the OKH. In 1944, however, what mattered most was that all of the Wehrmacht’s major ground operations had been planned by the OKH. The OKW had mostly been running a strategic defensive, with attacking actions planned by commanders in the field.

Thus (and this is a point of genuine importance) the great German winter counteroffensive, on which all their hopes rested, was to be planned by an OKW planning staff (under General Alfred Jodl) who had never planned a major ground operation before. The army staff, which had been fighting a vicious war with the Red Army for years, had plenty of experience, but this was not their theater. Unsurprisingly, their proposal bore all the hallmarks of amateurism and “by the book” planning.

The eventual OKW plan, named Wacht am Rhein - “Watch on the Rhine” after an old German patriotic song, somehow managed to be both unrealistic, audacious, and completely unoriginal and repetitive. The plan called for three German armies (5th Panzer, the newly created 6th SS Panzer, and 7th Army) to be concentrated in the region of the Ardennes forest south of Aachen. They were to assault the positions of the US 1st Army under General Courtney Hodges, and overrun them en-route to the Meuse River. 7th Army would break off its advance and take up a blocking position to the east of the Meuse, protecting the flank of the two Panzer armies, which were to cross the Meuse in the gap between Givet and Liege. From there, 6th SS Panzer would drive north to Antwerp while 5th Panzer covered the gap between Brussels and the river. If all of these objectives were met, the Germans would have retaken or at the very least blocked up Antwerp (the vital port feeding the ally war machine) and encircled no less than three allied armies on the northern bend the Meuse.

Purely as a map exercise, there was nothing overly creative about Watch on the Rhine. In fact, it bore a clear resemblance to Manstein’s famous “sickle cut”, by which the Wehrmacht had defeated France four years previously. All in all, it was a fairly textbook operation for a German officer corps that had been thinking about (and fighting) wars in this region for generations. Yet the plan was also hilariously, naively optimistic - it relied on very tenuous assumptions that the allies had no reserves and would react slowly and weakly to the attack (as the French and British did in 1940). It also called for the panzers to cover ground outrageously fast - the lead elements were expected to reach the Meuse (more than 100 miles from their start lines) on the first day. Finally, the operation assumed - as if this were a trivial matter - that the Panzers could refuel themselves on the go from captured allied fuel depots, and that the allied air force would be grounded by bad weather. Indeed, in something approximating a mental cheat code (or delusion), Jodl and his staff simply did not consider allied air power as a factor, writing in the assumption that the weather would be bad.

When the OKW finally revealed its plan to the men who would have to implement it - Model and Rundstedt - the initial reaction was something less than enthusiastic. Rundstedt argued that Antwerp was simply too far - “If we had reached the Meuse, we should have got down on our knees and thanked God—let alone try to reach Antwerp” - he said. As an alternative, Rundstedt proposed (and eventually cajoled Model into cosigning) Operation Martin - it would start similarly to Watch on the Rhine, but instead of crossing the Meuse and trying to bag a whole slew of allied armies, it would curl up the inside of the Meuse and encircle a smaller grouping of American divisions (elements of 1st and 9th armies) around Aachen. This was more reasonable, they argued, and most importantly of all would keep all the German forces on the east side of the Meuse, to avoid the complication of operating over a major river.

But of course, Operation Martin was a nonstarter. This was a classic example of a “small solution”, whereas Watch on the Rhine - which promised to encircle nearly half of the allied formations in Europe and capture their arterial port - was a “big solution.” This was familiar language that German planners had used many times before, and both the aggressive culture of the German military caste and Hitler’s own nature as an inveterate gambler forbade the small solution. Hitler and the Wehrmacht always went for broke, and in 1944 they did so again - and even Model and Rundstedt, whatever their reservations, gave full agreement to Watch on the Rhine and did their duties to implement it.

As was to be expected, of course, assembling the force for Watch on the Rhine was not a trivial task for a German army and state that had been pushed to the limits. Most readers are familiar with the fundamentals of late war German weakness - shortages of trained manpower, fuel, vehicles, and munitions - but there were other, more specific issues at play in the Ardennes region in 1944. The German assembly area was quite road-poor, and allied airpower meant that equipment largely had to be moved at night to avoid detection. Throw in a shortage of motor transport and you have a serious problem moving the requisite forces into their staging zones - a problem completely separate from the larger strategic quandary of building enough tanks and training enough men. The hilly forests of the Ardennes are not an easy place to congregate forces in ideal circumstances, let alone when the enemy is watching from the sky. It made for a great many night marches and laborious trips hauling ammunition and equipment in with teams of horses.

Military intelligence and deception had never been a strong suit for the German army - this was always a marked advantage for the allies, with the Anglo-Americans in particular specializing in cryptography and code breaking, and the Soviets having their particular form of military deception, famously called maskirovka. But with Watch on the Rhine the Germans gave it their best effort, seeking not only to hide their deployment with night approaches, but giving an overall impression that they did not intend to attack at all. They generated a stream of fake radio traffic referring to a “defensive battle in the west”, and even the name of the operation - Watch on the Rhine - carried a defensive connotation. Most importantly, however, the Germans generated an elaborate scheme designed to hide the headquarters of their various armies. Even as Sixth SS Panzer Army congregated for the attack, a fake headquarters for the army remained operational almost eighty miles to the north, complete with radio and railroad traffic in and out, giving a realistic impression that the army was in the line around Cologne. Additionally, an entirely fictional army (the "“25th Army”) was created in occupied Holland, with a facsimile army headquarters and the 10 fake divisions. Meanwhile, men and vehicles continued to trickle into the staging area in the east of the Ardennes.

Painstakingly, and with many delays, the Wehrmacht managed to assemble a genuinely impressive assault package for Watch on the Rhine - Nazi Germany’s last great force accumulation. Model had his three armies in the line (under his overall command in Army Group B) containing no fewer than 200,000 men, 600 Panzers, and nearly 2,000 assault guns, tank destroyers, and armored vehicles. In the grand scope of the war, this was not a world-beating force, but for the battered Hitlerian Empire it was an impressive package - as good as it was going to get. The Luftwaffe was even ready to make a rare appearance. Bad weather was expected to ground the air forces, but in the event that the weather cleared, the Germans had assembled more than 60% of their remaining inventory of fighter craft - nearly 1,700 planes - to contest the skies. One last army for one last battle. The date was set: December 16. It was snowing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.