The Passing of the Age: The Battle of Lepanto

History of Naval Warfare, Part 3

White founts falling in the courts of the sun,

And the Sultan of Byzantium is smiling as they run;

There is laughter like the fountains in that face of all men feared,

It stirs the forest darkness, the darkness of his beard,

It curls the blood-red crescent, the crescent of his lips,

For the inmost sea of all the earth is shaken with his ships.

They have dared the white republics up the capes of Italy,

They have dashed the Adriatic round the Lion of the Sea

So begins GK Chesterton’s poem Lepanto - an ode to the colossal battle fought between the Ottoman Navy and a coalition Christian armada off the coast of Greece in 1571.

Lepanto is a very famous battle, and one which means different things to different people. To a devout Roman Catholic like Chesterton, Lepanto takes on the romanticized and chivalrous form of a crusade - a war by the Holy League against the marauding Turk. At the time it was fought, to be sure, this was the way many in the Christian faction thought of their fight. Chesterton, for his part, writes that “the Pope has cast his arms abroad for agony and loss, and called the kings of Christendom for swords about the Cross.”

For historians, Lepanto is something like a requiem for the Mediterranean. Placed firmly in the early-modern period, fought between the Catholic powers of the inland sea and the Ottomans, then on the crest of their imperial rise, Lepanto marked a climactic ending to the long period of human history where the Mediterranean was the pivot of the western world. The coasts of Italy, Greece, the Levant, and Egypt - which for millennia had been the aquatic stomping grounds of empire - were treated to one more great battle before the Mediterranean world was permanently eclipsed by the rise of the Atlantic powers like the French and English. For those particular devotees of military history, Lepanto is very famous indeed as the last major European battle in which galleys - warships powered primarily by rowers - played the pivotal role.

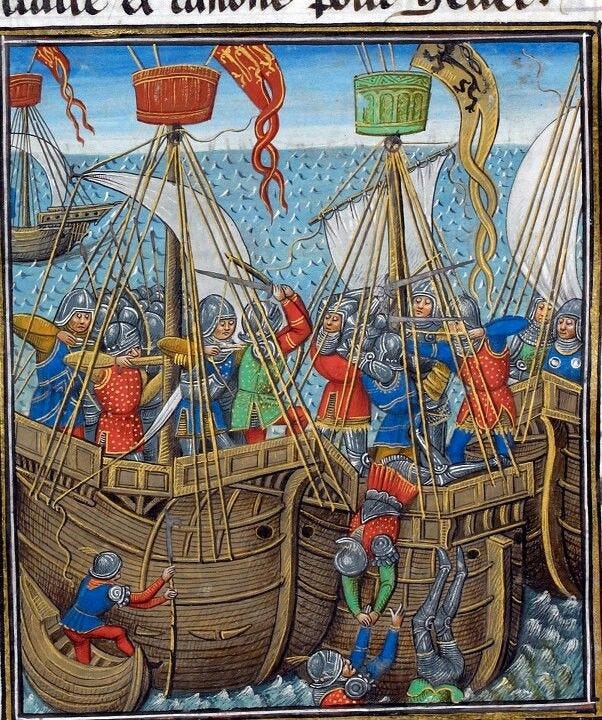

There is some truth in all of this. The warring navies at Lepanto fought a sort of battle that the Mediterranean had seen many times before - battle lines of rowed warships clashing at close quarters in close proximity to the coast. A Roman, Greek, or Persian admiral may not have understood the swivel guns, arquebusiers, or religious symbols of the fleets, but from a distance they would have found the long lines of vessels frothing the waters with their oars to be intimately familiar. This was the last time that such a grand scene would unfold on the blue waters of the inner sea; afterwards the waters would more and more belong to sailing ships with broadside cannon.

Lepanto was all of these things: a symbolic religious clash, a final reprise of archaic galley combat, and the denouement of the ancient Mediterranean world. Rarely, however, is it fully understood or appreciated in its most innate terms, which is to say as a military engagement which was well planned and well fought by both sides. When Lepanto is discussed for its military qualities, stripped of its religious and historiographic significance, it is often dismissed as a bloody, unimaginative, and primitive affair - a mindless slugfest (the stereotypical “land battle at sea”) using an archaic sort of ship which had been relegated to obsolescence by the rise of sail and cannon.

Here we wish to give Lepanto, and the men who fought it, their proper due. The continued use of galleys well into the 16th century did not reflect some sort of primitiveness among the Mediterranean powers, but was instead an intelligent and sensible response to the particular conditions of war on that sea. While galleys would, of course, be abandoned eventually in favor of sailing ships, at Lepanto they remained potent weapons systems which fit the needs of the combatants. Far from being a mindless orgy of violence, Lepanto was a battle characterized by intelligent battleplans in which both the Turkish and Christian command sought to maximize their own advantages, and it was a close run and well fought affair. Lepanto was indeed a swan song for a very old form of Mediterranean naval combat, but it was a well conceived and well fought one, and Turkish and Christian fleets alike did justice to this venerable and ancient form of battle.

Medieval Languishing

The Battle of Lepanto was fought in 1571, while the last entry in this essay series ended with a consideration of the Battle of Actium in 31 BC. The astute observer may notice that a significant period of time lapsed between these two events, and wonder whether it is possible that something interesting occurred in that intervening period. In fact, many things did happen between the 1st and 16th Centuries of the common era, but relatively few of those things were what we might recognize as naval battles.

After Octavian’s victory in the Roman Civil Wars, the Mediterranean again became a pacified internal zone of the Roman Empire, which left little possibility of major naval operations being necessary for several centuries. It was not until the disintegration of pan-Mediterranean Roman power in the 5th Century that Southern Europe and the inner sea again became a contested theater, but the intense geopolitical contest of the medieval period did not lead to a significant resurgence of naval combat. Still, it is worthwhile for us to consider medieval naval warfare, such as it was, as a prelude to early modern war and Lepanto. Although phrases like “the medieval period” and “the Middle Ages” can take on a somewhat nebulous meaning, I have always preferred to date the Medieval era from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 to the defeat of Byzantium in 1453, bookending the period with the two deaths of Rome.

For a variety of reasons, naval warfare was of relatively scant importance during the medieval era. Naval battles were relatively rare and generally smaller in scale than in the archaic world - in those many centuries, there were few naval operations that even remotely compared in scope to the great ancient battles at Salamis, Cape Ecnomus, or Actium. Medieval Europe had ships, of course - the most numerous being the modestly sized flat bottomed cogs which formed a mainstay of merchant fleets. In wartime, however, such vessels were primarily used to transport armies and their supplies, and they usually did so uncontested. Where naval battles did occur, they tended to be ancillary affairs and were not decisive of larger wars - in sharp contrast to the classical era, in which there were many major conflicts that were decided by the naval theater.

The de-prioritization of naval warfare during this period resulted from a dovetailing of strategic factors and preferences. First and foremost, there was a dearth of state capacity, with medieval states lacking the extractive powers and far reaching bureaucracies that characterized powerful archaic states like Rome or Persia. The weak and unconsolidated state had ramifications for many aspects of political life and geopolitical competition, this was acutely felt in the naval arena, to an extent that was disproportionate to the impact on land power.

The key difference between generating fighting power on land and sea in the medieval period lay in the decentralization of military preparedness and the latent power of the peacetime society. What we mean by this is that while medieval societies had the power to quickly raise armies from their peacetime resources, this capacity did not extend to warships. A class of landholding military servitors (which we popularly call knights) provided ready combat power, while peasants could be levied to fight in a pinch. Furthermore, the longstanding threat posed by raiding threats from the periphery - Vikings, Magyars, and so forth - led to the devolution of defensive responsibility. Centralized royal authority was utterly unable to react in a timely manner to such threats, and so defense became essentially a localized affair, delegated de facto to local lords and the fighting resources of the immediate region.

With most medieval societies therefore organized to generate defensive land power from their extant resources, states were, as a rule, simply not organized bureaucratically to maintain capable standing navies, as these were resource intensive forces which required specialized knowledge (both to build and operate) and significant expenditure even during peacetime. Where naval support was required for a war, it took a significant amount of time to amass and usually made use of merchant ships, as contracting or requisitioning existing civilian vessels was cheaper and much easier than raising a purpose built war fleet. Thus, the ships used in medieval naval battles - when they did occur - tended to be merchant cogs and barges, modified for combat.

As a result, medieval societies were geared for warfare on land, even when facing threats from the sea. The preeminent example of this, of course, was the Vikings. Popular portrayals of the Vikings tend to emphasize their extraordinary ferocity in battle, but the true “strategic asset” of the Scandinavians who ran wild in Europe in the 9th and 10th Centuries was their extraordinary seamanship. The Viking longship was an astonishing cultural artifact, capable of navigating rough open ocean while still being maneuverable and shallow enough on the draft to sail up rivers and beach itself for amphibious assault. The ability of the Vikings to cross the tumultuous North Sea and even venture out into the North Atlantic as far as Greenland and the North American coast in open hulled, single decked galleys was truly exceptional.

One thing the Viking longship was not, however, was a good platform for fighting on the water. Lacking any armament whatsoever, it sat too low in the water to board enemy vessels with ease, and there are scant references to what we might call pitched battle involving Viking fleets. Where such battles did occur, as at the Battle of Svolder in 999, combat seems to have involved lashing ships together to form an immobile floating fortress, rather than maneuvering in a recognizable fleet action. So while seamanship and shipbuilding were an essential element of the Vikings’ spread and power, the sea played the role of incurring tremendous mobility and striking range to Viking forces, rather than being an arena of combat. All of the most critical engagements between the Vikings and their adversaries, such as the Battles of Brunanburh, Rochester, Edington, Maldon, and Stamford Bridge, occurred on land. The example of the Vikings is greatly instructive, demonstrating that even in scenarios where the sea was the sole vector of attack for the enemy, scaled fleet operations were simply not a favored strategic recourse.

The simple fact that medieval Europe lacked dedicated institutions for naval warfare meant that there was a corresponding lack of specialized engineering, training, and expertise. As a result, medieval navies lacked a ship-killing weapons system. There is no record of the medieval use of rams, such as were used in archaic navies. There are incidents where the use of fire weapons is recorded - most famously by the Byzantines, who used a proprietary chemical mixture of quicklime, naphtha, and sulfur to create the equivalent of a medieval flamethrower - in almost all circumstances medieval naval combat centered on boarding action and the exchange of bowfire.

Because medieval warships were generally armed only with the personal weapons of the fighting men on deck, tactical methodologies favored efforts to fortify the ship, rather than to execute sophisticated maneuvers at sea. A few of these tactical trends bear enumeration.

In a battle between medieval warships, the most pressing and immediate danger came from the missile weapons of the men on the enemy deck, including crossbows, traditional bowfire, javelins, and occasionally jars full of caustic lime. Because battles were at the outset an exchange of personal missile weapons, one of the easiest and most cost effective ways to increase combat effectiveness was to simply increase the height of the ship, so that one’s own men were aiming downward at the enemy deck while being protected from enemy missiles by the railing of the ship. There was a concerted trend throughout the medieval period, therefore, to fortify vessels by constructing higher and higher fighting platforms with a protective wooden railing, particularly in the prow and the stern of the ship. Such fighting platforms became the origin of the terms forecastle and aftercastle as names for the front and aft decks, which remained in use long after the utility of such “castles” in combat disappeared.

Given the narrow parameters of a medieval sea fight as an exchange of missile weapons and boarding actions, the relative height and protective quality of these fighting platforms were frequently decisive in battle. Perhaps most notable example of this was the Battle of Malta in 1283, which took place in the “War of the Sicilian Vespers”. This was one of those esoteric medieval wars which is almost impossible to make sense of without a great deal of specialized reading - fought between states that no longer exist (chiefly the Crown of Aragon, based on Southeastern Spain, and the Angevin Kingdom of Naples in Southern Italy) for purposes that are essentially incomprehensible to us.

A full and dutiful exposition of this opaque conflict would be beyond our remit in this essay. What is interesting for our purposes was that this was one of the few medieval wars where there was a meaningful naval theater, given the fact that this was essentially a war between Spanish and Italian states over Sicily and to a lesser extent Malta, some 50 miles to the south. In 1283, an Aragonese fleet arrived off the coast of Malta and managed to trap a similarly sized Angevin fleet inside Malta’s Great Harbor. The Aragonese fleet had two distinguishing factors in its favor: first, it was led by a highly capable Admiral named Roger de Lauria, and secondly that its ships had been built up with exceptionally tall fighting platforms (“castles”).

When de Lauria’s fleet arrived at the mouth of the Great Harbor, he formed them up in a line across its mouth and then proceeded to lash his ships together with heavy chains, forming a unified barrier across the exit. Wary of being trapped in the Great Harbor, the Angevin fleet immediately disembarked from its protected anchorage at Fort Saint Angelo and rowed out to give battle. De Lauria, however, counted on the superior height of his decks to shelter his men from enemy projectiles, and ordered his men to return only a small amount of token crossbow fire. The heat of the day was spent with the Angevin fleet futilely futilely flinging crossbow bolts, jars of lime, and javelins at the high Aragonese fighting platforms, doing very little damage and causing few casualties. Once the Angevins had expended all their ammunition, de Lauria ordered his fleet to attack, and his men were able to fire down on the lower decks of their now helpless adversaries.

The Battle of Malta is a very useful illustration of medieval naval combat, containing in miniature many of the more universal principles. First and foremost, the battle was decided tactically by the use of small arms like javelins and crossbows, as the ships involved were unarmed save for the personal weapons of their fighting crews. In this case, the single determinant factor of victory was that the Aragonese ships were taller. The battle also demonstrated that, although rare and usually small in scale, medieval naval combat was extremely bloody, as the victorious side tended to massacre enemy crews. At Malta, the Aragonese killed some 3,500 Angevin personnel, taking only a small fraction of that number captive.

This was a standard practice of the times. At the Battle of Sluys in 1340, for example, a French fleet tried unsuccessfully to replicate de Lauria’s blocking technique, chaining their vessels together to prevent the English from entering the Scheldt River. Unfortunately for the French, a strong wind began to disorder their formation, and the English fleet attacked them as they were struggling to hold their line. The English more or less massacred the French to the man, killing some 16,000 in a single day.

The Battle of Malta also, however, illustrates the limits to the scale and operational import of naval combat in this era. The two fleets that clashed in the Great Harbor were very small - something like 20 vessels on each side. Yet even such a small engagement - a skirmish by the earlier standards of the First Punic War - was sufficient to put the Angevins in retreat and cement de Lauria’s reputation as the best admiral in the Mediterranean. Today, he is still generally regarded as the greatest admiral of the medieval era, on the basis of a career in which his fleets rarely exceeded 30 ships.

It has become increasingly common to push back on the previously popular motif of the medieval period as a “dark age” of stunted human development in Europe. Despite the fragmentation of state authority after the fall of Rome, the middle ages saw the emergence of new strands in European high culture, the consolidation of embryonic modern states, and major advancements in agricultural practices and military technologies. Many European states, like 13th Century England, enjoyed prolonged periods of remarkable stability and prosperity.

This period was, however, a dark age for the science of war at sea. With Europe’s military apparatus devolved to prioritize local defense readiness, states lacked the centralized fiscal-military apparatus, technical expertise, and logistical infrastructure to maintain sophisticated standing navies. This rendered naval battle a matter of expediency, using modified variants of civilian cogs. Battles could be extremely bloody, and had a propensity to turn into the wholesale slaughter of defeated parties, but these engagements remained mercifully small with fleets numbering in the dozens, rather than the hundreds which were frequently seen in archaic battles.

Naval warfare as a science and an art languished for centuries in Europe, waiting for the perfect admixture of ingredients to reinvigorate it. The needs of the navy were threefold: fiscal-military systems capable of financing fleet construction, an economic rationale to make such fleets a sensible use of funds, and a weapons system capable of destroying enemy ships outright, without resorting to a gruesome close order fight. They would get all three: the state, spice, and cannon.

The Advent of Sail and Shot

The development of the highly effective weapons systems that we know as the line ships of the classic age of sail were the result of synchronous developments in the technology of sailing and cannonry, along with the economic systems needed to make these complex and expensive vessels feasible. Taken together, these innovations produced the single most powerful system of power projection ever seen, with vessels that had the range and seaworthiness to attain global reach, and the firepower and capacity needed to bring flexible and formidable combat power to bear wherever they went.

The signal development which set off the rapid development in European seamanship was the reconquest of Iberia in the 13th and 14th centuries. This long period of protracted war against Muslim occupation spurred the consolidation of highly militarized and assertive monarchies in Portugal, Aragon, and Castile, serving as an ideal example of the principle that, although the state makes war, war also makes the state. The reconquesta produced states with a very particular nexus of traits: they were mobilized and had unusually high state capacity for the era, possessed of an expansive and assertive orientation motivated by the sense of an ongoing cosmic war with Islam, and - most importantly - they lay on Europe’s Atlantic bow, making the sea their natural vector for expansion.

It was not surprising, therefore, that Iberia (Portugal in particular) became the site of particularly dynamic innovation in ship design and navigation. By the early 15th Century, the Portuguese were probing further and further down the African coastline under the sponsorship of Prince Henrique, Duke of Viseu - known to history simply as “Henry the Navigator.” The vessel favored for these annual expeditions was the caravel - an indigenous Portuguese design which featured a shallow draft and lateen (triangular) sails. The caravel was ideal for exploration along the coast - it could run safely in shallow waters and sail very close to the wind, and it proved an ideal workhorse for working down Africa’s western coast, with Portuguese navigators steadily working out the shape of the continent and taking constant depth measurements as they went.

The caravel was, however, a limited vessel. It was precarious (to put it generously) in the open ocean, both due to its triangular rigging (which was inferior on the open seas to the square rigging characteristic of larger vessels), and its relatively small size, which made it both cramped and dangerous in rough seas. Most importantly, however, this was fundamentally a scouting and exploration vessel, which lacked the cargo space to actually function as a long range trading vessel. The caravel could hug the coast and plot routes to foreign markets, but it could not haul back large quantities of precious cargo once it had reached them.

It is a well understood fact of history that Spanish and Portuguese exploration in this era were motivated by a desire to procure direct access to the rich markets of the east, tinted with a religious fervor to project Christendom across the globe. Situated on Europe’s western edge, the Iberian states were cut off from the profits of the silk roads by both the Islamic powers, which controlled the Levantine coast, and the merchant empires of Genoa and Venice, which dominated trade on the Mediterranean. Most everyone understands that the Spanish and Portuguese wanted to outflank these middle men and procure direct market access for themselves.

What is less understood, or at least less appreciated, is that it was access to these markets that made the European naval revolution financially feasible. The construction of larger and more seaworthy sailing ships, like the hefty, square rigged carrack, was astronomically expensive. These were among the most complex engineering products then in existence, and required a tremendous pool of highly specialized (and expensive) manpower to design, build, maintain, and operate. When the Portuguese crown financed the construction of two large carracks and a 200 ton supply ship for Vasco de Gama’s first voyage to India, the navigator Duarte Pacheco Pereira wrote simply: “The money spent on the few ships of this expedition was so great that I will not go into detail for fear of not being believed.”

The tremendous expense of these vessels was only made bearable to the state due to the extraordinarily high profits to be made in spices, exotic goods, and specie like gold and silver which could be found in Africa (and soon, the Americas). When Sir Francis Drake circumnavigated the globe and returned safely to England in 1580, the value of his cargo (much of it looted from Spanish vessels) was more than twice the English crown’s revenue for the year. Little wonder, then, that the English went all-in on the project of maritime empire.

Perhaps this seems obvious and elementary, but this underscores a crucial strategic aspect of sea power in history. Naval power projection, rather uniquely, has the potential to be economically self-perpetuating. The range and carrying capacity afforded by shipping makes the ocean a unique pathway for exploiting far flung economic resources and penetrating foreign markets. A land-based imperium historically did not offer a similarly cost effective system of scalable economic exploitation. It was not until the invention of the railroad - a late development in the human story - that continental powers like the United States and Russia had a cost effective way to exploit the vast resources of their interior spaces. Maritime empires, in contrast, never struggled with this problem, and so naval power projection and wealth created a singular feedback loop for the states of Western Europe, with each making the other possible.

The Age of Exploration, spearheaded by the Spanish and the Portuguese, therefore had the effect of breaking the ocean wide open for Europeans - not only in the sense that they demonstrated the possibility of global navigation, but also in establishing the economic feedback loop which could empower an early modern state to assume the massive fiscal and logistical burden of maintaining a navy. A possible modern allegory would be the development of phantasmagorical methods to economically exploit outer space - like generating space based solar power, or mining the mineral resources of asteroids - which could suddenly make expensive space exploration financially self-perpetuating.

The arrival of larger and more stable sailing ships also happened to dovetail historically with the emergence of gunpowder artillery, providing the ultimate platform for this powerful new weapons systems. Gunpowder weaponry began to spread in Europe in the late 1300’s, initially in the form of irregularly sized cannons which fired arrows, bolts, and stone shot. By the end of the century they had acquired a clear role in battle as defensive weaponry which could be mounted atop fortifications; the Byzantines used primitive cannon to great effect and defeated an attempt by the Turks to capture Constantinople in 1396; the Turks would then famously use dozens of their own large artillery during their ultimate capture of the city in 1453. This was still, however, an embryonic weapons system at the dawn of the early modern era - deadly, but cumbersome, difficult to move, and dreadfully expensive to manufacture.

It was no small matter that gunpowder weapons were emerging as a powerful battlefield expedient precisely as the Iberian age of exploration triggered a colossal expansion in shipbuilding. Large sailing vessels and cannon were, from technical perspective, a perfect match, in that they provided solutions to each other’s problems. Early modern cannon were tremendously heavy and laborious to move, and required large magazines of gunpowder and shot to operate. This could be a logistical headache for forces marching overland, which could require dozens of horses to haul a single gun. For a ship with tonnage in the hundreds however, even a sizeable battery of cannon was hardly an undue burden. Cannon, in turn, solved the main problem of medieval naval combat, by finally providing a ship killing weapon.

It therefore ought to be no surprise that the adoption of massed cannon at sea was an inevitability which happened very rapidly. Vasco de Gama’s flagship the São Gabriel carried twenty cannon on its 1497 voyage despite being only a modestly sized 100 ton carrack, while the English Mary Rose, which was launched in 1511, had roughly 80 guns of various calibers. When combined with the prowess of the fighting men on board - honed by centuries of intense intra-European warfare and crusading - this was a recognizable prototype of the weapons system that would extend European power to virtually every corner of the earth. Sail and shot had come.

These developments, we reiterate, were wholly dependent on their economic context. These increasingly large and ever more heavily armed vessels were among the most complex feats of engineering and the most expensive investments that an early modern state could make, and they justified themselves by creating the very economic expansion that made this expense possible. This, however, was not universally true. China, for example, achieved tremendous feats in navigation and shipbuilding, but it possessed its own vast inner world and colossal markets, leaving it ultimately disinterested (in both the economic and spiritual sense) in going abroad in search of foreign lands and wealth. Meanwhile, in the Mediterranean, there was no real possibility of a rapid economic expansion. This was a closed sea with a fully explored and intimately known perimeter, with established risks and rewards. In such familiar confines, a more familiar form of war would prevail for a while longer.

Old Reliable: The Galley in the Early Modern Period

The first thing that immediately stands out about the Battle of Lepanto as a major galley battle was how late it was fought. Lepanto was contested in 1571 - nearly eighty years after the Spanish had reached the Americas under Columbus and the Portuguese had arrived in India by circumnavigating Africa. Lepanto took place exactly 60 years after the launch of the famous English warship Mary Rose - a recognizably advanced sailing vessel armed with some 80 cannon.

Lepanto is thus temporally located firmly within the early age of sail. By this time, sailing vessels were crossing entire oceans; Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition had circumnavigated the globe, and sailing ships with broadside cannon were becoming a fixture in many European navies. And yet, when the Ottomans and their Catholic adversaries clashed off Greece, they did so with rowed vessels and a combat methodology that was largely similar to that utilized by the Romans, the Carthaginians, the Greeks, and the Persians. This is evidently very odd - in chronological terms, it would be as if the American navy launched sorties in Vietnam with First World War vintage biplanes.

This can give rise to the impression of primitiveness or a lack of imagination by the practitioners of 16th Century galley warfare. While a well armed carrack like the Mary Rose was bristling with many dozens of heavy cannon, a Mediterranean galley of the day would have been armed with, at most, three heavy guns, aimed forward from the prow of the ship - since the broadside of a galley was occupied by hundreds of oarsmen, it was obviously impossible to mount cannon there. Surely such a weakly armed ship represented an obsolete and archaic throwback - a nautical dinosaur awaiting extinction?

In fact, the galley retained its usefulness late into the 16th century due to a variety of economic, strategic, and geographic factors at play in the Mediterranean. The men who fought at Lepanto were not stupid, but were simply plying a well established form of warfare that had proven itself in the unique arena of the inner sea, and the galley as a weapons system can only be appreciated in the context of a broader system of warfare which prevailed in that time and place. In 1526, for example, the Venetian war office made an explicit decision to further experiment with galley designs, rather than pursuing the sailing carracks that were in use in Western Europe. It would require substantial hubris to presume that Venice, then one of the most educated, wealthy, and sophisticated states in Europe, would make such a decision out of ignorance, rather than well grounded tactical and strategic concerns.

To begin to understand this, we must view the Mediterranean Sea the way that strategists of the day saw it: as a single and vast littoral, or coastal zone. The Mediterranean is essentially tideless, splattered with islands, and ringed with accommodating sandy beaches, natural harbors, and shallow approaches. This created a tactical orientation which was fundamentally amphibious, and within this framework the galley remained the favored weapons system for centuries after the advent of cannon artillery. The crucial point is that weapons systems do not exist in a vacuum - it was not simply a matter of galleys being replaced by sailing warships, but rather that these vessels were used to prosecute entirely different systems of warfare.

The sailing, cannon broadside vessels which would eventually come to predominate the world offered a potent new strategic opportunity: they made it possible to control the sea. This was not only due to their powerful armament (with each ship possessing the firepower of a massed artillery battery, they offered the potential to shatter enemy fleets and sink cargo vessels with ease), but also due to their carrying capacity. A deep-draft sailing ship can carry hundreds of tons in cargo, allowing it to stay at sea for months at a time - this provides a permanent and extremely powerful force projection at sea. The ultimate manifestation of such sea control is the blockade: having driven the enemy surface fleet away, an armada of sailing warships can exert a suffocating control over access to the ocean.

A galley cannot do this. With most of the galley’s hull space dedicated to the rowing crews, they have a cargo-to-crew ratio that is very poor compared to a sailing vessel, and they are thus unable to stay at sea for extended periods of time. The galley was therefore not a tool for controlling the sea, but a weapon for projecting fighting power from the sea to the land, and vice versa. In the Mediterranean, the ability of the shallow-draft galley to operate right up against the shore, penetrate into riverways, and to ground itself on the beach was extremely valuable.

The galley thus continued to fill a critical role in a Mediterranean system of naval warfare that was very different from that which prevailed in the age of sail. This was a system of combat which focused not on major fleet actions and blockades, but on projecting power towards the land, with the main object of these operations being the networks of bases that supported long range galley operations. This was a schema that was intimately familiar to the Romans, who saw most of their naval conflicts resolved through the control of such bases. Carthage was defeated in the First Punic War through the capture or isolation of its harbors and depots, and in the later Roman Civil Wars it was Caesar Augustus and his admiral, Marcus Agrippa, who defeated Antony and Cleopatra by striking at their chain of supply bases and fortresses. This basic operational formulation had not changed much by the early modern period, and networks of island bases still remained the main object of naval combat.

There was one other important consideration which kept the galley relevant, however, and this was the cost and availability of cannon. In the 16th century, cannons were not yet subject to easy mass production. Methods for casting cannon (which produced the barrel in a single cast piece out of a mold) were beginning to appear by mid-century, but much of the European world’s artillery continued to be produced with variations of the hoop and stave method, which laboriously welded the barrel together out of multiple strips of metal, similar to the way a wooden barrel would be produced with planks. While the details of the metallurgical processes are perhaps interesting to some, the upshot was that cannon were still very expensive and limited in quantity. Given that the Mediterranean powers needed to provide cannon for both ships and their fortresses, while retaining enough pieces to serve their land forces in sieges (both the Spanish and the Ottomans in particular maintained large forces on land which competed with their navies for cannon), it is not surprising that more modestly armed galleys with a handful of bow guns remained in common use, while the heavily armed broadside ships took much longer to come into play.

And so, when the fleets clashed at Lepanto, the vessels were a refined but intimately familiar variation of the archaic galleys that had plied Mediterranean waters for thousands of years. Allowing for some variations among the combatant nations (more on this in a moment) a “standard” 16th century galley was approximately 136 feet long and some 18 feet wide, powered by roughly 200 oarsmen manning about 24 banks of oars. Vastly improved shipbuilding techniques made these early-modern galleys much more seaworthy than their ancient predecessors (unlike Athenian galleys, they did not take on water and so did not need to be hauled onto the beach to dry out), and of course they were distinguished by the presence of gunpowder weaponry. Lepanto galleys possessed a small battery of heavy cannon which aimed directly out of the bow, which when fired would recoil on their wheeled mounts back into the gap between the rowing benches. For flank protection against boarding, a variety of small swivel guns were mounted on the flanks of the ship, and of course a company of marine infantry prowled the deck.

The important point to emphasize, however, is that the maneuvering aspects of these ships was essentially unchanged since ancient times. This was both because they continued to be powered by oarsmen (and thus they moved essentially the same way as archaic ships), but also because the cannon battery aimed forward out of the bow of the ship - it could therefore only be aimed by turning the ship in combat. Because the cannon aimed statically forward - just like the rams on ancient Greek and Persian vessels - the ship maneuvered much the same in combat, aiming to achieve a shock attack on the vulnerable flanks and stern of the enemy vessel. And so, while cannons are obviously significantly more powerful than a ram, these remained vessels engineered to attack head first. The smell of gunpowder and the crack of the cannon were new, but an ancient admiral watching from a distance would have found the frothing oars and the maneuvering of the fleet to be comfortingly familiar.

Out With a Bang: The Battle of Lepanto

The backdrop for the great clash of Lepanto was the slow and inexorable expansion of Ottoman power around the Eastern Mediterranean rim, which brought it into conflict with the maritime empire of Venice. Venice’s strategic position and orientation were highly analogous to that of ancient Carthage: their “empire” consisted of a network of colonies and bases strung along the coasts and islands of the Adriatic and Mediterranean. The critical function of these positions was primarily to provide control over the sea route between Venice and the Levantine coast, with a chain of bases and fortified harbors protecting the shipping which was the lifeblood of the wealthy Venetian economy.

The keystone position which became the basis of the Ottoman-Venetian War was the island of Cyprus. From a geostrategic perspective, the importance of Cyprus is refreshingly easy to understand. As the easternmost island in Venice’s control, it was the critical node ensuring Venetian access to the Levantine coast. Cyprus also, however, sat directly on the sea lines of communication between the Ottoman heartland in Anatolia and their provinces in Egypt. In essence, Cyprus sat at the intersection of two critical sea lanes - a north-south line between Anatolia and Egypt, and an east-west line between Venice and the Levant. It is not particularly hard, then, to understand why the Ottomans coveted it.

When an Ottoman armada arrived at Cyprus in 1570, Venice faced a disturbing strategic outlook. Venice was a wealthy but thinly populated mercantile power, ill constructed for a protracted slugfest with the much more powerful Ottomans. The naval prowess of the Turks was by this point a well established fact - in 1538, the Ottoman Navy had smashed a coalition Christian fleet at the Battle of Preveza (fought, incidentally, exactly where the Battle of Actium had taken place some 1600 years prior). Another decisive Ottoman victory at the Battle of Djerba in 1560 had the Turks sitting 2-0 in major fleet actions. A third round would be no laughing matter, and Venice needed allies.

It was thanks to the intense and energetic intervention of Pope Pius V that Venice secured the assistance of Hapsburg Spain and her satellites, with the 1571 formation of the “Holy League”. The terms of the alliance called for the fleets of the allies to rendezvous in late summer at Messina, on the Sicilian coast, for a joint campaign into the Eastern Mediterranean. Command of the joint fleet would fall to Don Juan of Austria - the illegitimate half-brother of the Spanish King, Philip II.

And so we come to Lepanto - the swan song of the galley; violent codicil to a three thousand year old form of Mediterranean warfare. The battle was shaped and made possible by a serendipity which is often rare in war: both sides were highly motivated to seek a decisive battle, which meant that both sides had a carefully devised operational scheme that was thought out in advance. Lepanto was a battle that both sides wanted and planned for, and both the Turks and the Holy League managed to implement their battle plans and achieve their desired deployment.

The Turkish motivation to fight is easy to understand - they were under express orders from the Sultan, Selim II, to bring the Catholic fleet to battle and destroy it. As for the Holy League, their dynamic was more nuanced and subtle, and had much to do with Don Juan’s attempts to mediate an uneasy alliance.

The various constituent allies had different motivations for joining the war, and correspondingly different senses of urgency. For the Spanish, the war with the Turk was primarily a religious matter - another chapter in their long, cosmic struggle with Islam. Venice, on the other hand, was fighting for concrete geostrategic interests - particularly to save their colony in Cyprus. The Venetians also fought with an important handicap. Because Venice had such a relatively sparse population, mobilizing their fleet required them to raise levies of fishermen, merchant sailors, and other civilian laborers. Coming to a war footing therefore brought Venice’s economy to a full halt, and was extremely expensive to maintain. The Venetians were therefore strongly motivated to bring the war to a swift conclusion. Don Juan also had to worry about the various ancillary allies, particularly Genoa, which had joined the Holy League while continuing to trade with the Ottomans.

Don Juan therefore had to plan a campaign around strategic disagreements in his coalition, with the very real possibility that some of his fleet might withdraw from the alliance or even defect. The longer the campaign dragged on, the worse these aggravations were likely to become; therefore, he, like the Turkish Admiral, Müezzinzade Ali Pasha, was also determined to bring about a decisive battle as soon as possible.

After rendezvousing in Sicily late in the summer, the Holy League fleet - some 212 ships in all, crossed the Adriatic and arrived at the island of Kefalonia off the western coast of Greece on October 6th. The mass of the Turkish fleet, 254 vessels in all, was stationed just 65 miles to the east in their naval base at Nafpaktos, in the Gulf of Corinth. The Venetian name for Nafpaktos is Lepanto. The following day, both armadas came out to meet at the entrance of the gulf. It was October 7, 1571.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.