Endless ink has been spilled pontificating on precisely how and why Europeans came to rule the world in the modern era. There are a variety of what we might call grand, unified theories of European domination, ranging from the geographic determinism of “Guns, Germs, and Steel” to more mystical notions of “western civilization” and the ability of philosophical concepts to convert readily to hard power. In the modern political climate, with its trite anathematization of all things colonial and imperial , the topic has increasingly become toxic in its entirety - European hegemony is taken to be synonymous with western civilization, and vice versa.

If one can move past the ideologically charged caricatures of rapacious Europeans prowling the earth in search of loot and slaves, a moment of brief reflection might reveal how counterintuitive Europe’s age of global empire was. In the late middle ages, Europe was both more politically fragmented, less populous, and significantly less wealthy than the imperial states of the east. Although the trope of the middle ages as a barbarous dark period have increasingly been left behind, there is little question that regions like China, Central Asia, India, and the Middle East enjoyed a higher level of political consolidation and state capacity, and were both more populous and richer than Europe in this period. Militarily, Europe was frequently on the back foot amid deep geopolitical penetration by the Ottomans and the Islamic statelets of North Africa.

Even more strange, however, is the fact that the key progenitors of European empire were poorer and more politically marginal states even within Europe itself. It was not the economic and technological powerhouses in Italy and Germany that spread European power to the ends of the earth, but relatively poor, unpopulous, and ancillary players like Portugal, the Netherlands, and England.

Our purpose here is not to dwell at length about the European spirit, for good or ill, but instead to examine the evolution of the weapons system that won the earth for Europe: the full-rigged sailing ship armed with broadside cannon. The spiritual and intellectual content of European civilization is another matter entirely from the technical methods that gave it supremacy thousands of miles from its home shores. Europe was certainly not the only part of the world to possess gunpowder in the 16th and 17th centuries, but it was Europe that successfully married cannon to ship and produced the phenomenally powerful navies that ruled the waves in the age of shot and sail. It was these ships that gave Europe the means to rule the world, creating the economic basis which made possible the construction of ever larger fleets, empowering the entrenchment of greater state capacity, and prompting the systemization and professionalization of naval warfare.

The Advent of Empire: Portugal and the Battle of Diu

At a cursory glance, the first arrival of Portuguese ships in India must not have appeared to be a particularly fateful development. Vasco da Gama’s 1497 expedition to India, which circumnavigated Africa and arrived on the Malabar Coast near Calicut consisted of a mere four ships and 170 men - hardly the sort of force that could obviously threaten to upset the balance of power among the vast and populous states rimming the Indian ocean. The rapid proliferation of Portuguese power in India must have therefore been all the more shocking for the region’s denizens.

The collision of the Iberian and Indian worlds, which possessed diplomatic and religious norms that were mutually unintelligible, was therefore bound to devolve quickly into frustration and eventually violence. The Portuguese, who harbored hopes that India might be home to Christian populations with whom they could link up, were greatly disappointed to discover only Muslims and Hindu “idolaters”. The broader problem, however, was that the market in the Malabar coast was already heavily saturated with Arab merchants who plied the trade routes from India to Egypt - indeed, these were precisely the middle men whom the Portuguese were hoping to outflank.

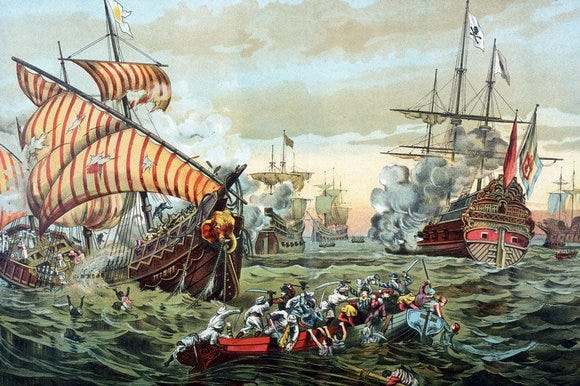

The particular flashpoint which led to conflict, therefore, were the mutual efforts of the Portuguese and the Arabs to exclude each other from the market, and the devolution to violence was rapid. A second Portuguese expedition, which arrived in 1500 with 13 ships, got the action started by seizing and looting an Arab cargo ship off Calicut; Arab merchants in the city responded by whipping up a mob which massacred some 70 Portuguese in the onshore trading post in full sight of the fleet. The Portuguese, incensed and out for revenge, retaliated in turn by bombarding Calicut from the sea; their powerful cannon killed hundreds and left much of the town (which was not fortified) in ruins. They then seized the cargo of some 10 Arab vessels along the coast and hauled out for home.

The 1500 expedition unveiled an emerging pattern and basis for Portugal’s emerging India project. The voyage was marked by significant frustration: in addition to the massacre of the shore party in Calicut, there were significant losses to shipwreck and scurvy, and the expedition had failed to achieve its goal of establishing a trading post and stable relations in Calicut. Even so, the returns - mainly spices looted from Arab merchant vessels - were more than sufficient to justify the expense of more ships, more men, and more voyages. On the shore, the Portuguese felt the acute vulnerability of their tiny numbers, having been overwhelmed and massacred by a mob of civilians, but the power of their cannon fire and the superiority of their seamanship gave them a powerful kinetic tool.

When the Portuguese returned yet again in 1502, this time once again under Vasco da Gama, they were still thinking about the massacre at Calicut and looking for revenge. They started by burning an unarmed ship full of Muslim pilgrims returning from Mecca, before engaging in a sequence of fruitless negotiations with the Zamorin (king) of Calicut, and beginning a blockade of the city. An attempt to lift the blockade and drive the Portuguese out predictably turned into a disaster. Despite mustering a significantly larger fleet (over 70 vessels against the 16 in De Gama’s armada) Calicut blundered into a disaster; the Portuguese took advantage of both their superior gunnery and favorable winds to remain at range and pummel the Malabar fleet, shattering it while taking only minor losses of their own.

The strategic situation in the Indian Ocean thus took the following shape. The Portuguese had originally aimed to establish a permanent trading post in Calicut, but relations had gone permanently sour (for obvious reasons), and they instead formed an alliance with Calicut’s enemy to the south, the Sultan of Cochin (a kingdom centered on the modern day Indian state of Kerala). Holding permanent, fortified positions in India was of supreme importance to the Portuguese, not only for purposes of basing and protecting their trade, but also to anchor them amid the seasonal winds of the Indian ocean. The Indian monsoon has a charming and useful reliability, with strong winds blowing from Africa to India during the summer, before reversing in the winter. This pattern gave the Portuguese a reliable current to make the circuit to India in a year, but it also meant that once they had ridden the summer Monsoon in, they could not leave until the winds reversed late in the year. The seasonality of the winds meant, in essence, that Europeans could not simply come and go any time they wished, and made it paramount for the Portuguese to have safe harbors and solid bases. Eager to leverage Portuguese gunnery against his rivals in Calicut, the Sultan of Cochin was happy to provide just such a base of support.

The alliance with Cochin gave the Portuguese a permanent base in India which allowed them to devastate shipping around Malabar, and in December of 1504 they sunk almost the entirety of Calicut’s annual merchant fleet as it was en-route to Egypt. The disaster at last prompted the Zamorin to seek outside help, and envoys were sent to Cairo to request assistance from the powerful Mamluk Sultanate, which was already growing very tired of Portuguese aggression towards the Arab merchants operating in India. In 1507, a Mamluk armada arrived on the coast of Gujarat, basing themselves in the port city of Diu.

The war for the west Indian coast would therefore be fought primarily between the Portuguese, operating out of their base in Cochin, and the Mamluks, who were supported by (and had come to the aid of) the Zamorin of Calicut, the Gujarati Sultanate, and the prosperous communities of Muslim traders operating all along the coastline. In March of 1508, the Mamluks managed to ambush and defeat a small Portuguese flotilla at the port town of Chaul, killing the son of the Portuguese viceroy, Dom Francisco de Almeida, and alerting the Portuguese to the fact that they now faced a serious adversary who would attempt to dislodge them from India altogether. Almeida called in all available ships to rendezvous at Cochin, and in December they set out for Diu, to crush the Mamluk fleet. After a cautious voyage up the coastline, they arrived near Diu in March, 1509.

The Muslim strategy in the ensuing battle was shaped first and foremost by the human considerations that often intrude on the rational calculus of war. Although nominally a consolidated allied fleet, the Muslim armada was in fact a tenuous joint force comprised of Mamluk vessels under the command of Amir Hussain Al-Kurdi and the local Gujarati forces of Diu, under the command of the local governor, Malik Ayyaz. The relationship between the two was, in a word, less than amiable, and hobbled by mutual suspicion - conditions which are rarely conducive to sensible military planning.

Hussain argued from the jump that they ought to sail out and meet the Portuguese in the open sea, while they were still tired from their long voyage and had not had time to formulate a battle plan of their own. Ayyaz, however, saw this as a ploy - fighting in the open sea would allow the Mamluks to break away and flee back to Egypt if the fight went poorly, leaving Ayyaz and the people of Diu to face the wrath of the Portuguese and shoulder all the consequences. Ayyaz therefore insisted that they ought to instead wait in the shelter of the harbor and let the Portuguese come to them. Nominal tactical arguments were made for this plan, but the real purpose - from Ayyaz’s perspective - was to prevent Hussain from abandoning him. Hussain then tried to override Ayyaz by simply ordering the entire armada to sail out, at which point Ayyaz had to scramble to override the order and call his own ships back. Thus, before the battle even began, the two Muslim commanders were fighting each other to a command stalemate.

These dynamics of mistrust pushed the Muslim fleet into the default strategy, which was to simply wait in the shelter of the city in a defensive position. There were certain tactical points to be made here, of course - the Gujarati artillery on land might be able to intervene in the battle, and the Muslim fleet might be safe from Portuguese maneuvering if it remained snug against the shore, but the larger problem was that Ayyaz and Hussain had ceded the initiative to a Portuguese enemy that was very eager to fight, and to fight aggressively.

In the end, the Muslim fleet deployed with its heavy ships - including the six carracks and six galleons of Hussain’s fleet and four Gujarati carracks - anchored in a snug line close to the shore, under the ostensible protection of shore mounted cannon, while a cloud of lighter vessels, mainly comprised of small oared vessels and light galleys, loitered farther up in the harbor. The plan, as such, seems to have been to draw the Portuguese into a fight against the shoreline so that the light vessels could sail out and swarm them in the rear. It was not a commendable design, but given the paralyzing distrust between the Muslim commanders it would have to do.

The mood in the Portuguese fleet could hardly have been more different. Almeida was emphatic that the coming battle would be decisive, not just in the local, tactical sense but in a more grand and historic way. He told his captains that “in conquering this fleet we will conquer all of India”, and made lavish promises of knighthoods, promotions, and rewards to every man in the event of victory.

The Portuguese battle plan hinged on tactical aggression, initiative, and superior gunnery. Almeida’s flagship, the Frol de la Mar (Flower of the Sea) transferred most of its fighting men to other vessels and prepared to fight as a mobile artillery platform, to loiter in the rear of the battle where it could offer fire support and allow Almeida to coordinate the fight. The remainder of the Portuguese fleet was prepared to sail laterally across the face of the Muslim fleet and soften the enemy with cannon fire before wheeling in for boarding action.

As the sun rose on February 3, 1509, a small Portuguese frigate sailed down the line of the fleet as it loitered and waited to commence the battle. As it passed each ship, it briefly stopped and a herald came aboard to read a proclamation from the Viceroy. This gesture underscored that Almeida was not only fully prepared and eager to fight, but also convinced that he was about to win a world-historic victory. The proclamation read, in part:

Dom Francisco d’Almeida, viceroy of India by the most high and excellent king Dom Manuel, my lord. I announce to all who see my letter, that on this day and at this hour I am at the bar of Diu, with all the forces that I have to give battle to a fleet of the Great Turk that he has ordered, which has come from Mecca to fight and damage the faith of Christ and against the kingdom of the king my lord.

After reading the proclamation, the herald reiterated the previously promised rewards of titles and knighthoods, and gave universal permission to loot the enemy in the event of victory. Having dispersed this message to the whole fleet, Almeida’s flagship fired a signal shot and the Portuguese began to spill into the harbor, sailing right past the shore batteries of the defender. To the great dismay of the Muslim fleet, the defensive fire from the shore guns had no great effect on the onrushing Portuguese armada. The lead Portuguese ship, the Santo Espirito, had its deck swept by fire which killed nearly a dozen men, but the line of Portuguese warships continued uninhibited and set on the static Muslim fleet.

The ensuing battle was shaped by a threefold Portuguese advantage in gunnery, armor, and tactical aggression, all of which were magnified by the disastrous decision by the Muslim commanders to moor their ships in a line with their sterns towards the shore - this rendered the Muslim fleet largely immobile and ensured that they could only fire their bow cannons, while the Portuguese vessels fired broadside volleys as they spilled into the mouth of the Diu harbor. The opening salvos of the Portuguese managed to sink a Mamluk carrack at the outset, and they continued to disgorge fire as they wheeled inward and slammed into the stationary Muslim warships, which remained largely immobile and fought like floating forts.

Portuguese fighting spirit was evidently extremely high, and their heavily equipped marines led ferocious boarding actions which, supported by the gunnery of the ships, slowly but surely overwhelmed the Muslim defenders. Hussain had some hope that his flotilla of light boats, which was loitering further up in the harbor, might swing the fight in his favor by swarming into the rear of the Europeans and boarding them from the stern, but this gambit was shattered by Almedia’s flagship. The Frol del Mar had remained aloof from the close quarters fighting and was prowling in the rear, offering fire support as it went; when the cloud of little boats came charging into the battle at full row, they ran straight into the Frol, which unloaded its cannon on them. The lead boats were smashed, leading to a congested and fouled mess which blocked the other vessels from entering the battle. The utter failure of this attempted swarming on the flank left the larger Muslim vessels trapped helplessly against the shore, where they were slowly but surely overwhelmed.

By the end of the day, Diu had turned into the most overwhelming Portuguese victory imaginable. Every one of Hussain’s 12 warships had been destroyed or captured, and of the 450 Mamluk personnel who had fought in the battle, a mere 23 had escaped - Hussain himself and some 22 men who had fled with him in a small boat. As for Hussain’s erstwhile ally, Ayyaz, he played his cards brilliantly in the end - after watching the battle from the shore, he brought Almedia an offer of surrender, pledged vassalage to Portugal, and sent the victorious Portuguese fleet a sumptuous gift of food and gold.

In the grand scheme of things, Diu was not a particularly large or complex battle. The victorious Portuguese fleet had a mere 18 ships, of which only 9 were heavy carracks, and there were at most 800 Portuguese fighting men and sailors present. For our purposes, however, the battle presents two highly notable elements.

Diu was a significant and early demonstration of the emerging European naval system as a tool for potent long range power projection. The ability of a European power - even a poor one like Portugal - to project military force thousands of miles from home, fighting and winning in the littoral of wealthy and vast foreign states, was an entirely new and shocking state capacity, and one which would obviously have earth shattering implications. The combination of massed cannon fire and heavy European infantry created a powerful tactical nexus, which could now be deployed and sustained with truly global reach. By the end of the 16th Century, the Portuguese would control a chain of forts and outposts stretching all the way from Lisbon to Nagasaki, and Portuguese sailors and soldiers would withstand decades of bloody warfare, repelling all attempts to dislodge them.

On a tactical level, however, Diu resembles a bridge between eras of naval combat. Although the workhorse vessel in the Portuguese fleet was the carrack, which was recognizable as a precursor iteration of the broadside warship, the fighting at Diu still centered on boarding actions. The Portuguese used their gunnery to great effect and sank large Mamluk vessels with cannon fire, but the cannonry was still largely utilized for softening up the enemy and supporting boarding parties. Most of the Muslim fleet was overwhelmed by the boarding actions of heavily armored Portuguese marines which, although tactically powerful, exposed the Portuguese to deadly bowfire - as a result, more than a third of the Portuguese who fought at Diu were wounded in a battle that they won decisively.

In this sense, although the Portuguese fought at Diu with recognizably advanced sailing ships capable of traversing oceans and operating thousands of miles from home, the combat itself was still a close order affair with gunnery operating in a supportive role. Notwithstanding the different design of the ships, the physics of this combat was not altogether different from that which was seen on the galleys at Lepanto.

Diu and Lepanto were fought on opposite ends of the 16th Century. For naval warfare, therefore, this century forms what we might call a historical estuary, where distinct eras blurred together. Lepanto was the swan song of a very old system of naval warfare involving close order combat between rowed galleys; Diu was fought with the prototype of broadside sailing ships, but they fought rather similarly to galleys. Lepanto was the last showing of an old form of warfare which had reached the point of obsolescence; Diu was the prologue to an emerging system of naval warfare that had not yet been fully developed. Cannonry, with the ship as a floating artillery battery, was clearly an extremely powerful weapons system, but the secret of its proper application had not yet been fully uncovered.

The Spanish Armada and the Birth of the Royal Navy

More than 4,000 miles from Diu, there sat a relatively poor and unimportant kingdom called England. In the mid-16th Century, England was a marginal and unimportant state in the grand turnings of European affairs. She had not yet consolidated control over Scottland, had no overseas possession apart from the port of Calais on the French coast, and her ability to project power or exert influence beyond her shores was minimal. Her role in the European system at this time was primarily that of a junior partner to the powerful Spanish and an antagonist to the French; during the reign of the notorious Henry VIII, England would fight three wars with France as an ally of Spain.

Relations between Spain and England reached a turning point with the onset of the English Reformation and the death of Henry VIII. Henry’s successor, the young Edward VI, became the first English king to have been brought up as a Protestant, but he reigned for only six years before dying at age of just 15. The throne then passed to his aunt, the Catholic Mary I, who reversed many of the church reforms and attempted to reassert Catholic prerogatives in England. In 1556, Mary was wed to King Philip II of Spain, providing a powerful foreign backer of the Catholic cause in England, and under his auspices Mary joined yet another war against France, which ended in victory for Spain, at the cost of England’s last possession on the continent when the French captured Calais in 1558. Mary died a few months after the loss of Calais and was in turn succeeded by Elizabeth I, who once more reversed the religious trajectory and favored the Protestants.

The whipsawing of the English religious balance of power, with the throne passing back and forth between Catholic and Protestant monarchs, of course has great importance in the story of England’s political development. What is interesting for our purposes, however, is the way this was perceived in Habsburg Spain, which was the most powerful Catholic state in Europe and a preeminent advocate of the Catholic cause. From the Spanish perspective, the English reformation threatened to tear England out of Spain’s orbit, robbing Spain of its influence over an ally that was usefully positioned on France’s northern flank. The death of Mary I was particularly devastating, in that it cost King Philip his direct influence over the English crown and replaced Mary with the Protestant Elizabeth.

It was within this context that Spain began to contemplate plans for what modern readers will instantly recognize as regime change. The Spanish initially supported plots to have Elizabeth overthrown and replaced with her cousin, the Catholic Queen Mary of Scotland - in response, Elizabeth had Mary imprisoned, forced her abdication, and eventually ordered her execution in 1587. Elizabeth further responded to these Spanish intrigues by backing the rebellion of Philip’s provinces in the Netherlands and commissioning privateers to attack Spanish shipping. From the Spanish perspective, England was on the verge of permanently slipping out of Spain’s orbit, and the time had come for more direct measures. Thus, the scheme for the Spanish Armada (colloquially called the “English Enterprise” in Spain) was born.

The Spanish Armada represented a remarkably ambitious attempt to settle the question of the English reformation once and for all. The plan, as such, was to muster an enormous fleet in Spain, sail through the English Channel, link up with a Habsburg ground army in the Spanish Netherlands, and then amphibiously land the army across the Channel to march on London, depose Elizabeth, and replace her with a compliant Catholic monarch. On the whole, this was an unprecedented scheme for the early modern era, combining as it did a massive fleet operation, amphibious assault, overt plans for regime change, and operations at great distance from the Spanish fleet’s home ports.

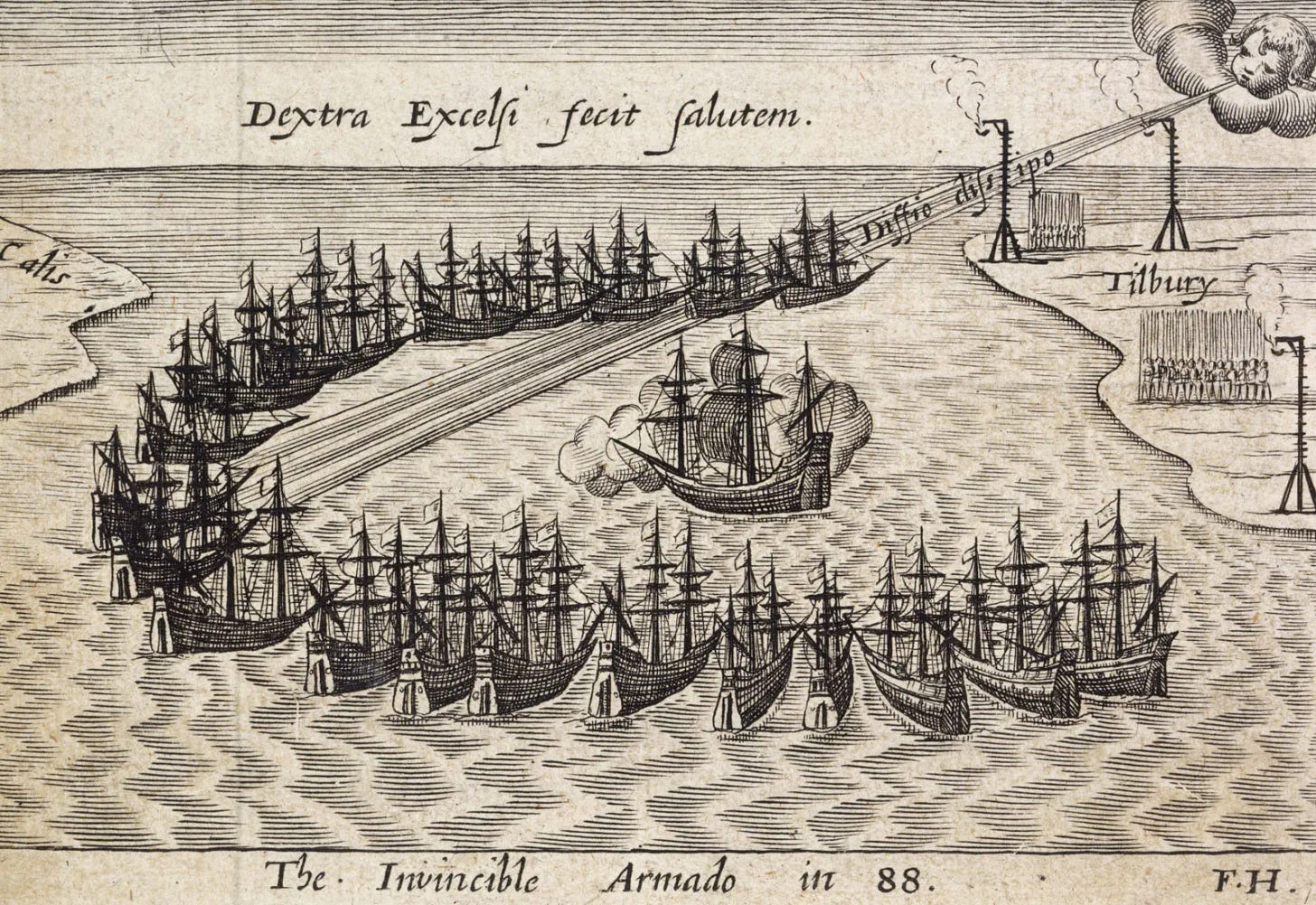

The Spanish initially had pretensions of maintaining the element of surprise, but given the sheer scale of the preparations involved (including not only assembling an enormous fleet in Spain but also staging the invasion army in the Netherlands) this proved impossible. By the summer of 1588, the famous Spanish Armada of 141 ships had been assembled in Lisbon (at this time, Portugal and Spain were in a state of personal union under Habsburg rule), and they set out for the Channel.

As the Armada entered the English Channel, it rounded a peninsula in Cornwall and was spotted on July 29 - the news of the Spanish arrival was then conveyed to London via a chain of beacons constructed for that purpose, and the English fleet readied itself at Plymouth to contest the channel. The following weeks of action would constitute, in many ways, the birthing operation of the Royal Navy, which had been formally founded by Henry VIII some 42 years prior.

The Spanish advantages were formidable. On paper, the English had more ships - around 220 against 117 in the main body of the Spanish fleet - however, of this large number a mere 34 English ships were purpose built warships in the royal fleet. The remainder largely consisted of armed merchantmen, few of which participated in combat. Thus, although the Spanish nominally had fewer hulls, they had a significant advantage in firepower, with up to 50% more guns. Furthermore, the complements of heavily armed Spanish marines on deck would give the Armada an insuperable advantage in close range fighting and boarding actions. All told, the Spanish had good reason to feel confident in a pitched fleet action, to say nothing of the danger that the English would face if the Armada succeeded in convoying the Hapsburg land forces over the Channel.

As the Armada worked its way eastward through the Channel in the final days of July, the English attempted in vain to engage them. The Spanish had adopted a crescent-shaped formation which protected their transport ships and barges by wrapping them in a tight perimeter of heavy galleons; given the danger inherent in grappling with these massive Spanish warships at close range, the English fleet under Sir Francis Drake was forced to snipe at them from range with cannon fire; this initial action failed to result in the loss of even a single ship on either side. English fortunes improved slightly on August 1 when several Spanish ships collided, setting one galleon adrift and allowing it to be captured by the English fleet. A second Spanish galleon was captured, albeit heavily damaged, when its gunpowder magazine exploded. On the whole, however, the Armada managed to reach Calais on August 7 entirely intact, where it anchored itself in the same defensive crescent formation to await a linkup with the Spanish ground forces.

In the dead of night on August 7, the Spanish fleet anchored off Calais was awakened by the alarms and bells of their lookouts. Eight burning hulks were drifting slowly towards the Spanish formation. These were eight large fireships - stripped down English hulls packed with gunpowder, pitch, pig fat, and any other flammable material on hand, then set ablaze and cut adrift at a distance from the Spanish anchorage. As the wind and current naturally drove them in at the Spanish, the Armada fell into a panic. Much of the Spanish fleet cut their anchors and scattered in a mad scramble to evade the path of the drifting fireships. While none of the Spanish vessels was burned, the fireship attack at Calais served the critical function of scattering the Armada and compelling it to break its tight crescent formation, which it had worked so hard to maintain ever since it entered the Channel.

The broader problem for the Spanish was that, by cutting anchor and scattering in a mad panic, the Armada had been driven eastward by the prevailing winds - it was now not only disorganized, but it would have to fight powerful currents if it wished to either return to anchor at Calais or regain its crescent formation. It was in this state of disorder, as the Spanish were scattered by the fireships and carried out by the wind, that the English fleet chose to attack. They closed in on the morning of August 8 as the Spanish attempted to sort themselves out near the town of Gravelines, some 20 kilometers up the coast from Calais.

The Battle of the Gravelines is one of those historical oddities where it appears at first blush that very little happened. The Spanish had left their home port in July with 141 vessels in their armada, and at Gravelines the British managed to sink just five. This would appear to be a fairly inconsequential battle then, judging by the loss calculus. In fact, Gravelines marked a crucial turning point in naval warfare, and created a tactical pivot around which the English began their rise to rule the waves.

As the Spanish Armada attempted to reconstitute its formation following the disorientation of the fireship attack, the English fleet sailed in to have a fight. Drake had discovered, upon studying the captured galleons in the channel, that Spanish ships were not laid out for efficient reloading of their guns, with the Spanish cannon tightly spaced together and the gun decks clogged with supplies. This was because the Spanish, like the Portuguese at Diu, still favored a tactical methodology inherited from their long experience with galley warfare. Spanish cannons were intended for softening up enemy vessels as a prelude to boarding action, and the vessel itself was thought of fundamentally as an infantry assault craft.

The Spanish therefore had a damnably difficult day at Gravelines, as Drake’s ships constantly stayed at the edge of grappling range, firing volley after volley at the Spanish fleet and constantly evading the enemy’s attempts to board them. While little of the tactical detail of Gravelines is documented, a few things are known for certain. First, we know that five Spanish ships were sunk and another six suffered significant damage. No English ships were lost. Furthermore, the battle ended at approximately 4 PM because the English fleet had expended most of its powder and shot; in contrast, recovered Spanish wrecks revealed large supplies of unused munitions. This supports the general sketch of the battle as one where the English were prepared to fight at range the entire time, while the Spanish struggled in vain to execute boarding actions.

Although the fighting at Gravelines sank only a small fraction of the Armada, the entire operation had been successfully scuttled. The Armada was scattered and disordered, had missed its rendezvous with the ground forces, and was now driven much farther to the east than it had intended. Returning to Calais would mean battling not only the English fleet, but also the winds. The Armada could not sail west back into the channel, it could not facilitate an amphibious invasion of England, and it could not defeat the English Navy. That left only one course of action, which was to return to Spain by sailing north and circumnavigating the British Isles. The Spanish rounded northern Scotland on August 20 and soon ran into yet another disaster, when the gulf stream carried them much closer to the Irish shore than they had anticipated. A series of strong winds drove many of their ships into the shore - particularly those that had been damaged in battle or by the long voyage - and claimed another 28 ships.

The Spanish Armada had set out with lofty strategic goals, preparing itself for the triple lift of fighting a major fleet action, facilitating an amphibious landing, and affecting regime change in England. Expectations were high, and the Spanish crown had mobilized impressive resources. Because the strategic intention was fundamentally to eradicate Protestant rule in England and resuscitate the Catholic monarchy, Philip II had even been granted the right to raise crusading taxes and grant indulgences to his men. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Armada represented the second front in a broader Spanish war for Catholicism. They had been victorious in the Mediterranean front against the Turks at Lepanto, but faltered in the English channel, and the costs were high. Of the 141 ships that were mobilized in July, a third were lost to combat and storms. The proportional loss of men was even higher, with many perishing from disease and accident along the way: 25,696 men set out, and 13,399 returned.

In the larger picture, the battle at Gravelines proved to be a tactical turning point in naval combat. The Spanish, influenced by their long experience fighting galley battles with the Turks in the Mediterranean, had continued to view their ships as infantry assault craft, with cannon batteries serving as supplemental weapons designed to support and facilitate boarding actions. Tactically, the Spanish attempted to fight Gravelines in a manner very similar to the way the Portuguese fought at Diu - firing limited salvos with their heavy cannon before boarding with their heavy infantry. In contrast, the English fleet used its ships as floating and highly mobile artillery batteries. The results vindicated the English model.

Going forward, the English would aggressively pursue ship designs which facilitated gunnery-centric combat. Most importantly, the English fleet would pioneer so-called “race built” ships. The word “race” is here a deformation of “raze”, and implied “razing” the fore and aft castles, creating a much sleeker vessel. The fighting castles, which continued to feature prominently on Spanish galleons, were useful in boarding actions, but they made ships top heavy and reduced maneuverability. By scrapping the fighting platforms altogether, English race built ships attained the familiar sleek shape and streamlined deck that gave them an insuperable advantage in ranged combat.

The English capital ships, which by the end of the 16th Century constituted the most powerful warships in the world, were essentially an admixture of four important technological changes:

Wheeled cannon carriages which rolled back into the ship upon firing, allowing for faster reloading.

Water tight porthole covers which could allow cannon banks to be placed on lower decks closer to the waterline.

Race built ship designs to make ships more maneuverable and less top heavy.

Full rigging, with three or more masts bearing square rigging.

While the English did not invent all of these important innovations, they were the first European Navy to pursue the systematic adoption of all four, and in doing so they cemented the superior combat power of ships deployed as mobile artillery batteries, rather than infantry assault craft. It was a warship built in 1514 for Henry VIII that first demonstrated the possibility of cutting gunports in the hull and placing banks of cannon close to the waterline, and it was Sir John Hawkins - Queen Elizabeth’s Treasurer of the Navy - who began cutting the fighting castles off of English ships to create the maneuverable race-built design.

The naval revolution which found its pivot at Gravelines is a profound example of the way that weapons systems can intervene in history, and even outweigh the larger structural factors of state power. Spain was a much more powerful, wealthier, and more populous state than England, with an exceptional military pedigree. It did not matter - the English had fully accepted the logic of the agile floating artillery battery in a way that the Spanish, who were accustomed to boarding fights in the Mediterranean, had not.

And so, the 16th Century presented three landmark naval battles which proved the passing of the age and the future of war at sea. At Lepanto (1571) the Holy League and the Turks fought a classical galley battle centered on boarding actions. At Diu, the Portuguese used solidly built sailing ships, but their cannons were utilized to support a galley-like boarding assault. Finally, at Gravelines (1588) the Spanish attempted to fight somewhat similarly to the Portuguese at Diu, but were utterly unable to either grapple with or return the fire of the more agile and relentlessly cannonading English fleet. The embrace of heavily armed ships optimized for broadside firing - the so-called “Great Ships” - gave the English the first recognizable Capital Ships on the seas and became the embryo of their eventual naval supremacy.

The Line Arrives: The Dutch and English Wars

The Dutch Republic and England fought three major wars at sea between 1652 and 1674. Curiously, these wars failed to make a lasting impression in either the English popular memory or the broader historiography of Europe and warfare. They are a point of interest in the Netherlands, but beyond Dutch shores they are little known and little regarded.

This fact is rather strange, because it was in these Anglo-Dutch Wars that naval warfare in the age of sail reached its mature and recognizable form, particularly through a series of radical and important innovations made by the Royal Navy - innovations which were frantically and aggressively copied by the Dutch. The Royal Navy’s eventual ascension to total global naval supremacy - the backbone of Britain’s century of global empire - was forged in decades of intense and close quarters naval combat with the Dutch. Perhaps it is little wonder, then, that one particular historian of the field, named Alfred Thayer Mahan, found these wars to be uniquely important and dwelt on them at great length.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.