The most famous warships in history tend to be known either for their wartime exploits or for their longevity and place of pride in their fleets. A few names that might come to mind would include the German Bismarck, which was pursued and sunk in a dramatic chase on the high seas by the Royal Navy; the HMS Victory, which served as Nelson’s flagship at Trafalgar; the USS Constitution, in service today with the US Navy as the oldest commissioned warship still afloat; or perhaps the carriers that fought at Midway, like the Enterprise, Hornet, and Yorktown, or Japan’s Kaga and Akagi.

It is ironic, then, that perhaps the most famous warship of all time, the HMS Dreadnought, had a service career that was both short and entirely light on kinetic action. Launched in 1906, the Dreadnought had an active lifespan of just thirteen years - barely that of a small dog - and by 1921, after two years in reserve, she was ingloriously sold for scrap. Today, virtually no artifacts of the ship survive, apart from a few small items like a decorated gun tampion (essentially a plug for the barrel of a gun) at Britain’s National Maritime Museum. In the brief years that she was on active duty, the Dreadnought fought no real battles and never fired at an enemy ship: her lone kill was the German submarine U-29, which was sunk off the coast of the Orkney Islands in 1915 when the Dreadnought ran her over.

The Dreadnought had, by any measure, a short and quiet service career. But this has little bearing on the enormity of her significance in the history of naval warfare. When she was launched in 1906, the Dreadnought marked a watershed development in ship design. Her form was the culmination of a dramatic evolution in warship design, which had been moving steadily forward throughout the latter half of the 19th Century with the adoption of steam propulsion, armored hulls, and exploding shells. From the moment the Dreadnought came off the slipway and settled her hulking girth into Portsmouth Harbor, every other capital ship in the world was obsolete, and she left her mark on the world’s navies by conferring her name to a new era of ship design: every ship built before her was now designated a “pre-dreadnought”.

It is easy, in the historiography, to find any number of appellations and praises for the Dreadnought. The “most powerful warship in the world”, ushering in a “revolution” in naval design - on and on it goes. This can lead easily to the conclusion that the Dreadnought’s design was implicitly accepted, or that her innovations were readily apparent to all - in other words, that it was obvious to everyone that this new class of warship, the modern battleship, was the future.

It was not. Although the Dreadnought was indeed the most powerful ship in the world when she launched, and a central component of British plans to maintain naval supremacy, the new battleships were hardly an icon of British triumph. In fact, the design of the Dreadnought came about against a backdrop of British strategic crisis, in which Great Britain’s strategic position began to decay in significant ways - and although the Dreadnought was undoubtedly an impressively powerful weapons system, she did not ameliorate the British strategic conundrum.

The Dreadnought, then, marked a departure point not merely in ship design, but in an emerging century characterized by geopolitical pressures and military-industrial processes that were virtually unrecognizable. The Industrial Revolution in Britain had uncorked a bottle and let out a genie wielding technological processes, financial considerations, and geopolitical pressures. The genie could give gifts and grant wishes, of course, in the form of bigger profits, bigger guns, bigger armies, and ever more powerful weapons systems, but the diffusion of this technology around the world looked ever more like a curse as time went on - and the genie could not be put back into the bottle.

Britain’s Strategic Crisis

At the core of the great naval developments occurring around the turn of the 20th Century was a systematic erosion of Great Britain’s strategic position. This strategic decay was of course a multivariate process which included the emergence of new great powers like Germany, Japan, and the United States, and the evolving industrial dynamics of the world. At its heart, however, the problem was very simple: in the latter half of the 19th Century, industrial technologies began to diffuse from Great Britain to the rest of the great powers, to the effect that British supremacy in industry and critical military technologies became an open question.

A brief perusal of the relevant economic statistics betrays a clear and sustained erosion of British supremacy. In 1880, Britain still accounted for nearly a quarter of global manufacturing output and was by far the leading industrial nation of the world. By 1913, it had fallen in absolute terms well behind Germany and especially the United States, which now boasted nearly 2.5 times Britain’s output. Already by 1910, Britain (formerly the world’s premiere steelmaking nation) produced only half as much steel as Germany and barely a quarter of American steel output.

The immense economic advantages enjoyed by the United States need little enumeration. America occupies a uniquely providential economic geography, being blessed with a pair of accommodating seaboards saturated with natural harbors, an internal Mississippi waterway that is both dense and far reaching to accommodate internal trade, superb growing regions, peaceful borders, and ample deposits of virtually every mineral resource thinkable. In short, it is a country with bountiful mineral and agricultural resources, internal waterways for moving them about, harbors for exporting them abroad, and no meaningful security threats.

The German case, however, bears closer scrutiny. Whereas the United States was characterized by boundless space, free of meaningful external security threats, Germany was intensely bounded in the middle of Europe, birthed into a firestorm of potential enemies all around it. German economic might was little like the American story, characterized by the uninterrupted exploitation of a vast geographic bounty, and more the product of powerful and aggressive German institutions - both of corporations and the state.

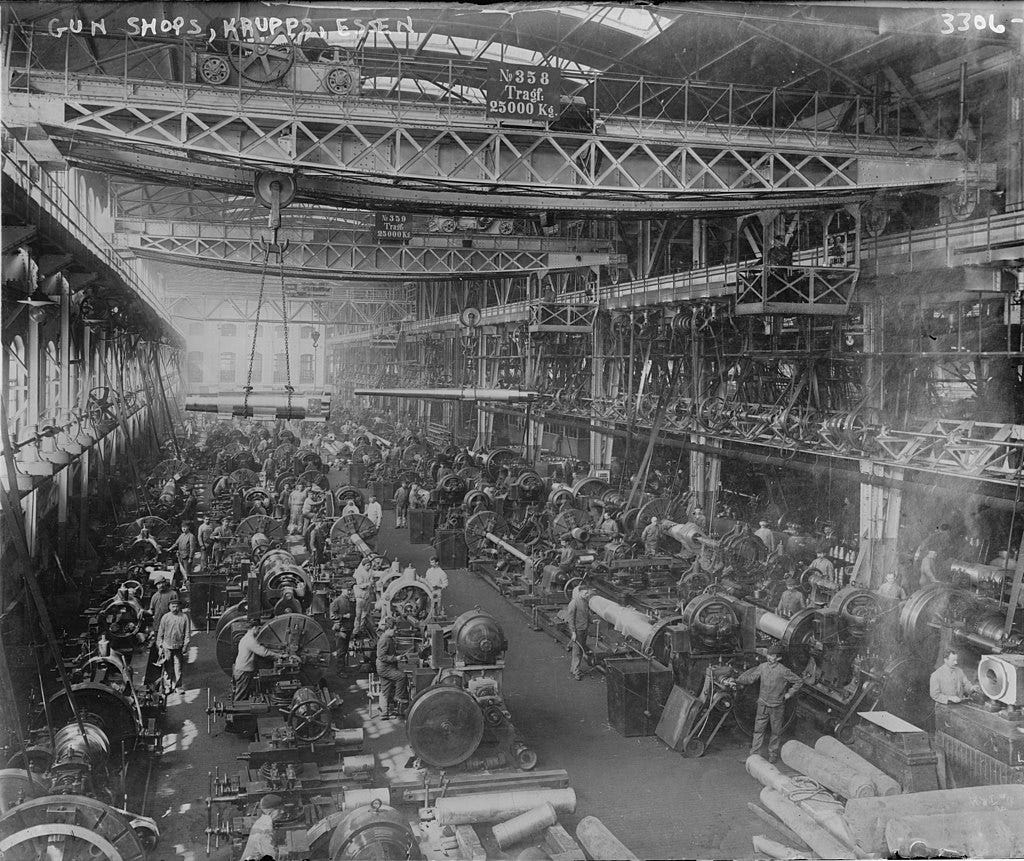

The German population grew rapidly into the 20th Century (German birthrates were forever a point of hand wringing for the French). The German population grew from some 49 million in 1890 to 65 million by 1910 - an increase of 32%, compared to an increase of just 3% in France (from 38.3 to 39.5 million) and 20% in Britain (37.3 to 44.9 million). Simultaneously, the consolidation of an impressive educational apparatus ensured that this growing population was highly literate and productive. Around the turn of the century, many European armies still reported high levels of illiteracy among recruits. In Italy, some 33% of recruits were deemed illiterate: the corresponding figure was 22% in Austria-Hungary and 6.8% in France, but a mere 0.1% in Germany. The rapid growth of such a young and educated population benefited not just the German army, but also the burgeoning roster of German industrial enterprises like Krupp, Siemens, AEG, Bayer, and Hoechst. Such firms dominated the emerging 20th Century industries like chemicals, optics, and electrics, and the intensive adoption of agricultural modernization and chemical fertilizers made German agriculture the most productive in Europe on a per-hectare basis.

The explosion of two industrial powers who could not only compete but even outstrip Britain (and one of them right in the heart of Europe) could have no effect other than directly undermining Britain’s strategic position. Matters were made worse, however, but the proliferation of advanced naval technology around the world - in many cases directly abetted by British firms.

In 1864, British military leadership had made the fateful decision to keep artillery production in the hands of the state-owned Woolwich arsenal, despite the emergence of private industrial firms, like the Armstrong company, who were capable of making state of the art naval artillery. Cut out of British government contracts, this let manufacturers like Armstrong with no choice but to seek foreign buyers. When Armstrong built an armored cruiser - the O’Higgins - for the Chilean government, it set off serious alarm bells about the basis of British naval supremacy. The O’Higgins was fast enough to easily outrun any capital ship of the day, but her powerful 8 inch guns made her more than capable of sinking targets in the lower weight class. This suggested a distinctive use case as a commercial raider, able to evade enemy battleships while preying on merchants. Chile, of course, was hardly a rival to Great Britain, but Armstrong’s exploits did not end there. All told, Armstrong would build 84 warships for twelve different foreign governments between 1884 and 1914, and frequently supplied technical systems more advanced than those in use by the Royal Navy at the time - for example, the powerful main battery of the Russian cruiser Rurik, launched in 1890.

The prospect of fast cruisers - optimized for speed and striking power at the expense of armor - was particularly alarming to Britain owing to emerging patterns of agricultural production. The advent of efficient steamships had drastically lowered seaborne transportation costs - a fact that was of the first importance for Britain, as it allowed for the mass import of cheap grain from places like North America, Australia, and Argentina, at costs far below the levels at which British farms could compete. As a result, between 1872 and the end of the century wheat acreage in Great Britain dropped by about 50 percent, and already by the 1880’s some 65 percent of Britain’s grain was imported from overseas. The prospect of swift enemy cruisers capable of intercepting grain shipments while evading the British battle fleets now assumed a potentially existential importance, as for the first time in history London contemplated the possibility that the interdiction of its trade could bring the island to the brink of starvation.

This raised the possibility of a dangerous asymmetry: might it be possible to nullify Britain’s centuries-old naval supremacy without building competing battleships at all? French naval theorists certainly thought so, and it was proposed that France could out-lever Britain on the seas with a fleet comprised entirely of fast cruisers and torpedo boats. Such a program had the additional advantage of being very cheap, with dozens of torpedo boats available at the cost of a single armored battleship. This financial calculus was particularly important to France: after the disastrous defeat at the hands of the Prusso-Germans in 1870-71, it was natural that building out the army should be Paris’s primary concern. Therefore, a naval program that promised to outmaneuver the British without eating into funds for the army had irresistible allure. In 1881, the French allocated funds for 70 torpedo boats (halting the construction of armored battleships), and in 1886 the new Minister of Marine, Admiral Aube, launched a new building program for 100 additional torpedo boats and 14 swift cruisers designed to raid enemy shipping.

Taken together, the decay of Britain’s naval supremacy is easy to sketch out. Great Britain had become uniquely vulnerable to asymmetrical warfare at sea, owing to its growing dependence on imported grain, at the same time that technical changes in the form of the torpedo and the fast cruiser gave her enemies the potential to exploit this vulnerability. To make matters worse, the diffusion of the industrial revolution to continental Europe and the United States raised the prospect that Great Britain might no longer be able to simply out-build her enemies. In a sense, the comforting and familiar dynamic of the blockade was now reversed: instead of a powerful British battlefleet insulating the home islands from invasion and blockading enemy ports, the home islands now faced starvation at the hands of fast and cheap enemy raiding vessels armed with torpedoes and modern naval artillery.

All of this was bad enough, but technical developments further conspired to make the mass of the British battlefleet obsolete. As late as the 1880’s, British battleships continued to use enormous muzzle loading cannon. These could do immense damage when fired at close ranges against accommodating targets (in essence, continuing the tactical methodology of Nelson’s day), but their slow rate of fire and inaccuracy threatened disaster in a fight against swift enemy torpedo boats and cruisers. It was not unthinkable now that a ponderous and expensive British battleship could be sunk by an enemy torpedo boat, darting in close to discharge its tubes and then zipping away again before the massive muzzle-loaders could be brought on target.

But it got even worse. In the late 1850’s, an American naval officer named Thomas Rodman discovered that propellant powder could be packed into grains with a hollow space on the inside, allowing the powder to burn on both the inside and outside of the grains simultaneously. This had the effect of stabilizing and equalizing the burn rate of the powder - instead of a massive initial burn that rapidly trailed off, the propellant would burn at a stable rate from ignition right down to the end of the burn. When combined with the introduction of nitrocellulose explosives (so-called “guncotton”), Rodman’s graining system promised a much more powerful, more stable, and essentially smokeless propellant system.

It was this leap which finally made the muzzle loading cannon obsolete. The more stable burn provided by Rodman’s system greatly increased muzzle velocity, because the burn rate of the charge remained constant after ignition (as opposed to older powder forms where the power of the charge rapidly decreased after firing). This required, in turn, lengthening the barrel to leverage this stable charge, providing both greater accuracy and range. Longer barrels, in turn, made muzzle loading obsolete at last - a series of powerful demonstrations by Krupp in 1878 and 1879 proved once and for all that breech loading steel cannon were the future.

The discomfiting reality was that the entirety of the British naval ordnance was on the verge of total obsolesce, both tactically and technically. Tactically, the muzzle loading batteries were too inaccurate and fired too slowly to engage fast enemy torpedo boats, and technically they could not compete with the new generation of breach loading artillery. In 1879, the British naval authorities decided that it was time to make the switch to steel breech loaders.

This, as it turned out, was much easier said than done. The sole provider of naval ordnance continued to be the state-owned Woolwich arsenal, which now faced not only the challenge of adopting entirely new gun designs, but also a total overhaul of its plant, which would have to be converted from wrought iron to steel. To make matters worse, the Board of Ordnance was under army control. Feeling intense pressure to renovate the navy’s artillery park, naval authorities now had to face both the physical limitations of the Woolwich arsenal and an army-led Board of Ordnance which was viewed as lethargic and unresponsive to the needs of the navy.

Frustrated by the intransigence of both the Board of Ordnance and the Arsenal officials, who seemed to be unapprehending of the severity of the situation, one enterprising officer decided to take matters into his own hands. This was Captain John Fisher - known to the British public and to history as Jackie Fisher. Recovering at home from a bout of malaria and dysentery developed on deployment, Fisher reached out to a journalist named W. T. Snead in 1884, and together they hatched a plan to force the government’s hand with a series of explosive articles under the heading “The Truth about the Navy”, published under the ominous pseudonym: “One Who Knows the Facts.”

These articles, which had a fantastic effect in Britain, argued in no uncertain terms that the Royal Navy’s supremacy was on the verge of extinction, and perhaps had already ceased to exist. It did achieve some measure of immediate results, with Parliament increasing the naval appropriations by some 50%. On a more historic scale, however, Jackie Fisher became a singular figure in both modernizing the Royal Navy and in breaking down the traditional barriers that had existed between the service, private industry, and politics, creating a nexus between them that is very familiar to us. Fisher, in effect, ushered in the military industrial complex.

Fisher’s rise was meteoric, born of his own ambition, his political acumen and willingness to flaunt convention, and his intense preoccupation with what he saw as a technological crisis. While older and more conservative officers felt that it was their duty to simply make the most of whatever funds the political authorites chose to allocate, Fisher was willing to go the mat - first anonymously and then publicly - to argue for the Navy. His ascension furthermore tracked very closely with the conversion of the naval artillery: in 1883 he had been made commandant of the naval gunnery school, and in 1886 he made the leap to Director of Naval Ordnance, and in 1892 he was an Admiral, Third Sea Lord and Controller of the Navy - in control of all naval procurement. By 1904 he was First Sea Lord: the highest ranking officer in the navy.

Throughout this ascent, Fisher served as the icebreaker plowing a new path of relations between the navy, private industrial firms, and politics. This was partially the result of a changing British political substrate. In 1884, the British franchise widened dramatically without a commensurate expansion of the income tax. This meant that there were now millions of new voters with a keen interest in economic conditions - particularly reducing unemployment - who were little concerned with how this might be paid for.

As a result, after 1884 there was a clear turn in British politics towards what we would now recognize as fiscal stimulus - particularly because there was a depression in 1884 precisely as the franchise widened. Economic depression suddenly made it seem more pressing to pass large naval appropriations to generate work and employment in private industry. In October 1884, the First Lord of the Admiralty suggested to Parliament that “if we are to spend money on the increase of the navy, it is desirable in consequence of the stagnation in the great shipbuilding yards of this country, that the extra expenditure should go… to increase the work by contract in the private yards.” The idea of a senior officer stumping for a larger naval bill on the basis of job creation, unthinkable just a few decades ago, now had a sudden sublime logic to it that was irresistible to politicians.

At the same time, Fisher pioneered a growing nexus between the military and private industry. The most important change in this regard came in 1886, after Fisher’s promotion to director of naval ordnance. Frustrated with the lethargic Woolwich arsenal and fixated on what he viewed as a critical technological gap, Fisher demanded (and was given) permission to purchase anything from private manufacturers that Woolwich could not supply more quickly or cheaply. On paper, Fisher hoped to stimulate competition between the arsenal and private producers, but the reality was that Woolwich would never be able to match the capital investment needed to match private lines. Armstrong, for example, had reacted to the emergence of Krupp as a competitor in foreign markets by investing in both a new steel mill and a shipyard, and was thus willing and able to immediately begin delivering guns to the Navy while the Woolwich arsenal was only beginning its foray into breech loading guns.

In essence, Fisher’s tenure as Director of Naval Ordnance allowed private manufacturers, of whom Armstrong was the most famous but not the only, to systematically undercut the more expensive and cumbersome arsenal system, granting a de-facto monopoly to private industry. This was the birth of the British military-industrial complex, with the feedback loops and personnel sharing that still characterize this system today, albeit much stigmatized.

Today, it is common to read outraged complaints about the incestuous relationship between armaments manufacturers, politicians, and military officers. At the risk of making an apologetic for this system, it is critical to understand that in the late 19th Century this system emerged more or less as an imperative of state security, without the negative connotations of corruption that exist today. In other words we could say that while there are many distasteful aspects of the modern military-industrial complex, no great power could survive the 20th Century without one.

Indeed, from very early on it became necessary to inculcate a close cooperation between Naval leadership and military industrialists, largely because of the sheer complexity and cost of naval engineering. Fundamentally, the Navy was buying very large, complex, and expensive products, which necessitated a close working relationship between procurement officers and private industrialists. Most famously, William White, who served as the Admiralty’s Director of Naval Construction, came directly from Armstrong, where he had worked as the company’s chief ship designer. But White was hardly the only such example, as personnel moved back and forth between state and private employment in an estuary of armaments design and fabrication.

The effect was not only to align private designs more closely with the needs of the navy, but also to accelerate the pace of change. Prior to the 1880’s, engineering and innovation had been largely driven by private inventors performing autonomous experimentation. This was a highly speculative enterprise with no guarantee of financial return - Armstrong discovered this firsthand in the 1860’s, when his breechloading guns (although definitively the superior system) were passed up by conservative officers in favor of muzzle loaders from the Woolwich arsenal.

In such an environment, technological change was bound to be relatively incremental, simply because private industrialists were unwilling to spend heavily on R&D with no assurance of return. By the mid to late 1880’s - the start of the “Fisher Era”, if you will - the growth of naval budgets and the close cooperation between Navy and industry provided an escape route. Now, the Admiralty could provide financial assurances to reduce the risk of expensive research and development, and even guide the process of innovation. Technological progress thus became a top-down, guided affair, rather than a process driven by private experimentation. In effect, the Admiralty set parameters for new systems - performance metrics for a gun, or an engine, or a torpedo, or an optical sight, and so on - and the engineers at private firms worked to meet them. It was now possible for invention and technological changes to respond to the needs of the service, rather than the service adopting its tactics around available technology.

The most famous example of this - and a truly revolutionary one - was a weapons system designed to counter the rising threat of fast torpedo boats: the quick firing artillery gun. The Admiralty asked for a very specific weapons system: a gun capable of firing at least twelve rounds per minute, with the range, accuracy, and power to destroy an enemy torpedo boat beyond the 600 yard range limit of the day’s torpedoes. By 1887, Armstrong had a gun that met all the design criteria, utilizing a hydraulic recoil system to automatically return the gun to its firing position after each shot. When combined with improvements to the breech system, this became the recognizable prototype of most modern artillery systems, which can fire in quick succession while remaining trained on target.

The quick firing gun was not only an effective tactical solution to enemy torpedo boats, but a powerful example of command technology, with innovation progressing towards concrete objectives laid out by naval authorities, rather than moving haphazardly at the auspices of private experimentation. Another such example was a new class of ship - the torpedo boat destroyer, which morphed into the vessel that we simply call the destroyer. Essentially a marriage of the quick firing gun with innovative new tube boilers, the concept was a fast and agile vessel that could screen battlefleets to intercept enemy torpedo boats before they could close to threaten capital ships. By 1897, the Royal Navy was fielding destroyers capable of making 36 knots - more than doubling the speed of warships just a decade earlier.

Taken together, it is clear that the mid-19th Century created a strategic crisis for the British which they answered by unleashing a military-industrial revolution, with the encouragement of Jackie Fisher. The diffusion of industrial capacity abroad, the development of new asymmetric warship types like torpedo boats and fast cruisers, and Britain’s growing dependence on imported grain all threatened to upend a centuries old calculus of British naval supremacy. Matters further came to a breaking point when developments in gunnery made the Royal Navy’s muzzle loading naval artillery (and the Woolwich arsenal that manufactured it) obsolete.

Facing both a technical and a strategic crisis, the British opened up a new nexus between political bodies, naval authorities, and private industrialists which promised to propel the Royal Navy to future glories. Close working relationships with major manufacturers like Armstrong allowed the Navy to drive innovation and procure ordnance in quantities that the old Woolwich arsenal, venerable though it was, could never hope to match. Meanwhile, the political apparatus discovered that naval appropriations were popular both on patriotic grounds and as a mechanism for job creation. Taken together, the entire apparatus of industry, technology, and finance were reaching the escape velocity needed to propel warfare at sea to a higher form.

The Rising Sun at Sea: Tsushima

While Britain busied herself responding to a systematic decay of her strategic position, unleashing an embryonic naval revolution in the process, equally dramatic changes were happening on the far side of the world in another island nation. The emergence of Japan as a modern and assertive power was among the most important geopolitical developments of the 19th Century, rivaled only by the American Civil War and the unification of Germany. The Japanese story, however, was endlessly surprising. Germany and the United States were well understood and intimately familiar nodes in the European mental map, with obvious potential as future powers - the question was only one of what sort of political arrangement would emerge to harness that power. Not so with Japan.

The Japanese revolution generally features in history books under the innocuous name of the “Meiji Restoration”, which belies the enormity of the changes in Japanese society which occurred in relatively short order. When the future Meiji Emperor, Mutsuhito, was born in 1852, Japan was still a pre-modern and fundamentally feudal country characterized by an extreme level of feudal decentralization, with over 270 minor polities ruled by petty warlords (Daimyos). Nominally ruled by a military head (the famous Shogun) who exercised power in the name of a politically neutralized emperor, the reality of Japanese political life was decentralization, warlordism, and strict isolation from foreigners.

The lifespan of a single man, then - in this case, Mutsuhito the Meiji Emperor - contained the wholesale transformation of Japan into a virtually unrecognizable modern state. The Boshin War (1868-1869) successfully overthrew the Shogunate and returned power to Emperor, and in the following decades the Meiji court would unleash a flood of reforms on Japan which reversed, practically in their entirety, the previous trajectory of the country. Japanese isolation, formerly a strict policy, was abolished and replaced with an intentional program to solicit foreign advisors and engineers, as Japan sought to remake itself into a modern state. Heavy land taxes on the peasantry and burgeoning silk exports financed the construction of modern industrial plants, railroads, and shipyards. Simultaneously, old feudal power structures were dismantled and the Imperial government pressured the privileged Samurai class (which numbed in the millions) into becoming productive civil servants and army personnel.

In short (and we can never do such a monumental event justice in such a short space), Japan transformed itself from prototypical colonial prey into an embryonic imperial power. Pre-Meiji Japan was precisely the sort of state which had traditionally been devoured by European powers: insular, fractured, and listless. Under the Meiji government, this Japan was transformed into a centralized Imperial state which consciously and aggressively sought modernity by adopting the best technological and bureaucratic practices of the day, even at the cost of transgressing ancient Japanese social taboos and coming into direct conflict with conservative Samurai.

Conveniently, the navy was one of the few areas where Japan had already opened itself to foreign influence even before the Meiji restoration got underway. A series of mid-century dustups with European fleets had highlighted the need for naval modernization, such that even the conservative Shogunate could not ignore it. In 1862, a British merchant was killed by the retinue of a local Daimyo, and when a small British armada appeared offshore the following year to demand restitution, it was able to bombard the city of Kagoshima with impunity. Almost simultaneously (in 1863), a joint western armada was able to force control of the Shimonoseki Strait, which separates the Japanese home islands of Honshu and Kyushu.

Basic prudence dictated that Japan, as an archipelago, would have to become a naval power to have any prospects in the world, and so the Shogunate had already begun soliciting foreign engineers (primarily British and French) to assist with the construction of modern naval arsenals, with a handful of warships purchased from Dutch, British, and American shipyards. We could say, then, that the Navy was one of the few arms of the Japanese state that was already open to foreign influence and modernization even before the Imperial restoration made this the norm.

Naturally, however, the development of the Imperial Japanese Navy (formally established in 1869) accelerated amid the more widespread reforms of the Meiji Period. Although the Royal Navy was widely seen as the gold standard to be emulated, it was in fact the French that provided the most powerful influence in the early Meiji period. This was precisely the time that the French were espousing their ideas for a budget fleet comprised of fast torpedo boats and cruisers which, in theory, could sink expensive capital ships at a fraction of the cost. This had obvious appeal to the Japanese, who were modernizing the entire state on a shoestring budget, and Japan’s 1882 naval appropriations bill laid the foundations for a fleet predicated on torpedoes, naval mines, and fast cruisers.

Both Japan’s foreign policy and the design of her fleet would take a sharp turn in the last decade of the 19th Century, with China serving as a crucial fulcrum. The Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) featured a series of largely unbroken Japanese victories, but there were still important lessons to be learned.

In particular, the Battle of the Yalu River (September 17, 1894) revealed the limitations of the French-style fleet design predicated on cruisers and torpedo boats. The Japanese did win the battle rather handily - shattering a Chinese fleet in the bay at the mouth of the Yalu, off the coast of Korea. However, the Chinese armada did possess a pair of German-built ironclad battleships which proved largely impervious to Japanese gunnery: they were only defeated after the remainder of the Chinese fleet had been swatted away, permitting torpedo boats to come in at close range.

This is not to remotely imply that the Yalu River was anything but a decisive Japanese victory, but for Japanese senior officers observing the battle, the resilience of the two Chinese battleships was slightly discomfiting, and seemed to indicate that a fleet comprised entirely of torpedo boats and cruisers was inadequate. It followed logically, then, that future phases of fleet expansion would incorporate capital ships, and the Japanese turned towards a more conventional, Mahanian battle fleet along British lines.

Secondly, the outcome of this first Sino-Japanese War did much to embitter Japan against the European powers and intensify their proclivities for a kinetic foreign policy. The chief cause of this was the so-called “Triple Intervention”. What happened was this: in the wake of Chinese defeat, a treaty was signed renouncing Chinese influence over Korea and ceding both Taiwan and the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan. Almost immediately after these terms were ratified, however, a joint diplomatic intervention by Russia, Germany, and France urged Japan to renounce its claim on the Liaodong Peninsula in exchange for a larger financial indemnity from China. Japan acquiesced under this European pressure, only to watch the Russians swoop in afterwards and obtain a 25 year lease on the peninsula, where they established a naval base at Port Arthur in 1898.

The Japanese, rather fairly, felt that they had been bullied and swindled, with the Russians taking a critical position that had been rightfully won with Japanese blood. To make matters worse, the new Russian position at Port Arthur, along with the new Trans Siberian Railway (which opened in 1904), put Russia in a position to move into Korea, which was now the main theater of empire for Japan.

In short, the Sino-Japanese War marked an important first chapter in Japan’s imperial story. Her victories against the Chinese fleet gave the modernizing Japanese navy an important base of experience and demonstrated that the growing fleet could not rely completely on torpedo boats but would require proper battleships, and the subsequent diplomatic wrangling embittered Japanese opinion against the European powers, particularly Russia. In the wake of this war, Japanese foreign policy would become increasingly muscular. Tokyo would sign an alliance with Great Britain in 1902, intended to deter further meddling by the French and Germans, and the Japanese battlefleet would be built out even further with capital ships. The stage was set for Japan to try her strength against a European power, and avenge herself on Russia.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, then, constituted an attempt by Japan to sterilize the encroachment of Russia towards Korea and Manchuria. The war began with a surprise attack on the Russian base at Port Arthur, with the Japanese beginning their assault several hours before a formal declaration of war. While Americans would later be scandalized and outraged at the undeclared attack on Pearl Harbor, this was in fact a well established trick in the Japanese playbook: at Port Arthur and at Pearl Harbor, Japan began its two largest wars against outside powers with a surprise attack on the enemy’s main naval base.

The full scope of the Russo-Japanese War is beyond our remit here, but we will make a few brief comments on its overall character. Japan’s surprise attack failed to capture Port Arthur, but they were able to successfully bring it under siege and largely sterilize Russia’s Pacific Fleet in the process. The Russians made a variety of attempts to break out and concentrate their fleet for action, but were unable to do so. Naval mines - a relatively new technology - played an important role for both sides, serving to both keep the Russian fleet in Port Arthur and the Japanese out.

On land, this war was a muddled affair. The Russians and the Japanese each had a difficult problem to solve. For the Russians, the main issue was that their operational possibilities were narrow and left little room for creativity: the Russian armies railed into the region had a singular objective (break the siege on Port Arthur), which left them no other course of action than to try and fight their way down the rail line from Harbin (see the map above). Thus, the largest land battle of the war, Mukden, was fought precisely on this rail line. Fighting literally thousands of miles from home in Russia’s remote far east, it was impossible to supply these armies without rail, and this fact meant that the Russians simply could not maneuver or try anything clever. In a word, their operational planning was extremely predictable, with their line of advance and supply chained to the rail line.

For the Japanese, the problem was that their tactical aggression and initiative were giving them a preview of the First World War, and Russian rifle fire and artillery frequently inflicted terrible losses. At the Battle of Nanshan, for example (which cut off the land approach to Port Arthur), the Japanese suffered more than 6,000 casualties in the process of overrunning a relatively small Russian defending force of perhaps 3,800 men. Although the Japanese were victorious at Nanshan, in that they did capture the Russian positions, their losses were thrice that of the Russians. At the Battle of Mukden, Japanese casualties were likewise very heavy, with more than 75,000 killed or wounded.

In essence then, the overland campaigns of the Russo-Japanese War had a unique and frustrating logic, in that the Russian Army was tactically proficient (it could inflict significant casualties on the Japanese), but operationally sterile, trying as it was to advance in a linear and predictable fashion down the railway line to rescue the besieged garrison at Port Arthur. Mukden was a paradoxical battle which was superficially indecisive; but to win the war, the Russians had to break through to rescue Port Arthur, therefore even a stalemate at Mukden constituted defeat for the Russians.

It was in this context that we come to our topic of interest here: the Battle of Tsushima. The strategic framework for the Russians was very simple: Port Arthur was besieged and therefore needed to be rescued. The overland rescue had come untracked at Mukden, with the army unable to proceed any farther. Therefore, all hopes for the salvation of the Port Arthur garrison came to rest on the Russian Baltic Fleet, which was dispatched at ultra-long range from Petersburg to Port Arthur. There is a persistent myth that the Russians were denied the use of the Suez canal by the British after a jumpy Russian captain opened fire on British fishermen in the North Sea, thus needlessly extending the voyage by forcing them to circumnavigate Africa. While the incident with the British fishing ships did occur as reputed, it had no relation to the ability of the Russian fleet to traverse Suez: the journey around Africa was necessary from the start, as the draught of the newer Russian ships was too deep for the canal.

With Suez closed to them, albeit by engineering particulars rather than British remit, the Russian Fleet was compelled to steam out into the North Sea, around Iberia, and thence down the entire length of Africa, across the Indian Ocean, around Indochina, and then north towards Korea. In total, this was a voyage of about 18,000 nautical miles which took seven months. Without any exaggeration, we can therefore call the Baltic Fleet’s attempted rescue of Port Arthur the longest range combat operation of all time. The logistics of the voyage were complicated even farther by the idiosyncrasies of the Russian Navy. First and foremost, Russia - unlike, say, the British - did not possess a network of far flung coaling stations to support the fleet - which meant the Russians had to manage a tending force of colliers and supply ships. Secondly, because the Baltic Fleet had been designed as a coastal defense force intended to fight in the littoral of the Baltic, many of its ships were simply not designed for a global voyage nor crewed by sailors with robust experience on the high seas.

This cumbersome fleet, now asked to operate at the absolute limits of thinkable range, was put under the command of fifty-three year old Vice-Admiral Zinovi Petrovich Rozhdestvensky. He certainly cut a striking figure - tall, dignified, and energetic, known for being a high strung workaholic (he regularly went sleepless for days at a time). A British rhyme described him thusly:

And after all this, an Admiral came,

A terrible man with a terrible name,

A name which we all of us know very well

But no one can speak and no one can spell

Russia is by convention a land power, and given its geography it is natural that the army should always have place of pride and importance in the country’s defense and power projection. In 1905, however, the Russian Navy - and the Baltic Fleet in particular - had elements that were essentially modern and capable. The core of the fleet sailing to far east consisted of four Borodino Class Battleships, which had been completed in 1901-02, and were thus slightly newer than their Japanese equivalents. The Borodino class was equipped with what was, at the time, state of the art weaponry, armor, and powerplants, much of it designed in collaboration with French and German engineers. On the whole, although the Japanese had significantly more ships on aggregate, much of this came from armored cruisers and torpedo boats, while the Russians had more battleships.

Functionally, the Russian fleet was at a disadvantage in almost every area: it had fewer ships, fewer mid-caliber guns (like the 6 and 8 inch batteries on Japan’s cruisers), and it was operating very far from home. Furthermore, the Borodino class had been designed with an eye towards protection from torpedoes, which meant that its heaviest armor was below the waterline. Much of the superstructures above the water, including the coning towers and gun turrets, had little armor to speak of. This indicates, in general, that around the turn of the century the design of modern battleships was still in flux, and there was no consensus as to whether armor ought to be optimized to defend against torpedoes or against the enemy’s big guns. The Russians did, however, have one distinctive advantage: they had more big guns (of the 10 and 12 inch varieties). Therefore, if the ensuing battle was fought at longer ranges, to take the Japanese cruisers out of the action, the Russians would have a boxer’s chance.

What the ensuing Battle of Tsushima would demonstrate (beyond the obvious fact that the Japanese were to be treated with deadly seriousness), was the critical importance of two specific capabilities: speed and fire control. We will make a brief digression to examine fire control in particular before treating with the battle itself.

Fire control, as such, simply refers to the ability to coordinate accurate fire at range, and entails a spectrum of technical capabilities including range finding, optics, and correction. At Tsushima, the Japanese fleet utilized a new system of fire control which decisively demonstrated its superiority over older methods. There were certain technological advantages in play, of course - electric firing mechanisms, superior telescoping sights, and state of the art rangefinders - but beyond this, the Japanese had pioneered a new methodology which proved to be decidedly superior.

Traditionally, the fire control system was dissipated: an artillery officer and his assistants would estimate the range to the target and transmit the data to the gun crew commanders. After firing the first shot, these gun crew commanders would make adjustments to the range by observing the splash of their shells in the water - splashes behind the target meant the range had to be reduced, and vice versa for splashes in front of the target. The problem with this system of fire control is that, by giving responsibility for adjusting range to individual gun crew commanders, the turrets became desynchronized, with each turret commander independently tinkering with the range. Furthermore, with all the gun crews adjusting their fire independently, it quickly became difficult to tell which splashes came from your shells and which came from the other turrets on the ship.

At the Battle of the Yellow Sea in 1904, the Japanese began to implement centralized fire control, which gave responsibility for calculating new ranges to the ship’s artillery officer and his team. Under this system, all the gun turrets used the same range for each subsequent salvo - the result was that there was now a single set of splashes (with all guns firing in unison). Instead of each gun crew commander straining to watch the splashes and then make his own adjustments on the fly, the ship would fire a synchronized salvo and then wait for the adjusted firing parameters to be calculated by the artillery officer and his technical specialists. When combined with state of the art rangefinders and optics purchased from the British, this would give the Japanese a considerable advantage in accuracy. The rate of fire might be slightly reduced, since the gun crews had to wait for the new firing parameters to come down from the artillery officer, but the Japanese had learned that the increase in accuracy was well worth the slight delays that came from centralizing the range calculations.

A memorandum from Fleet Admiral Togo expressed the new system thusly:

Based on the experience of past battles and exercises, the ship's fire control should be carried out from the bridge whenever possible. The firing distance must be indicated from the bridge and must not be adjusted in gun groups. If an incorrect distance is indicated from the bridge, all the projectiles will fly by, but if the distance is correct, all the projectiles will hit the target and the accuracy will increase.

The Japanese fleet was also faster. In this case, the matter was not merely a difference in the technical capabilities of the ships, but the fact that the Russian fleet (having sailed tens of thousands of kilometers) had worn its boilers down to the bone, and the powerplants of the vessels were badly fouled by smoke and particulate pollution. This advantage in speed would prove crucial, particularly given the more numerous Russian big guns. If the battle was fought at extreme ranges, the Russians would have the advantage in firepower, but because the Japanese were faster, they were able to dictate the range of the engagement and fight at distances that kept their cruisers (with 6 and 8 inch guns) in play.

In short then, the Russians came to Tsushima with plenty of firepower and a powerful nucleus of modern battleships, but they were slower than the Japanese and at a significant disadvantage in fire control, owing to better Japanese rangefinders and the methodological advantages of centralized fire control. These two basic capabilities - speed and accuracy - would make all the difference.

Before the battle could be joined, Admirals Togo and Rozhdestvensky had to make difficult deployment decisions. The Russian fleet had departed its Baltic ports in October of 1904, under orders to relieve the besieged garrison at Port Arthur by sea. These orders had become obsolete on January 2, 1905, when Port Arthur surrendered to the Japanese Army. This did not, however, prompt a recall of the Baltic Fleet, and Rozhdestvensky proceeded under revised orders to reach Vladivostok, link up with the surviving squadron of Russia’s Pacific Fleet, and bring battle to the Japanese navy.

From this accrued an obvious geographic problem. Vladivostok lies on the continental coastline of the Sea of Japan - so named because it is an almost entirely enclosed sea, walled off in all directions by the Japanese home islands. Only three deepwater channels offer access to the Sea of Japan: these are the Soya, or La Pérouse Strait (between the islands of Hokkaido and Sakhalin), the Tsugaru Strait (between Honshu and Hokkaido), and the Tsushima Strait which separates the Japanese home islands from the Korean Peninsula.

To reach Vladivostok, Rozhdestvensky had to choose between taking the straight route through Tsushima and circumnavigating Japan to slip through the Soya strait in the north. The Soya route was significantly longer, adding more than 1,000 miles to a Russian voyage that had already strained the limits of long range operations. Despite the distance, there were factors recommending it, as the Tsushima straits would bring the Russians right past several major Japanese naval bases. If the Russians chose the longer route and were able to sweep around the Japanese home islands mostly undetected, there was a good chance that they could catch the Japanese fleet out of position and reach Vladivostok unmolested. In the end, however, Rozhdestvensky opted against the Soya route due to a combination of distance and fears that the Soya Strait (only 25 miles wide) might be heavily mined.

So, Rozhdestvensky chose to steam straight into the strait of Tsushima and head directly for Vladivostok. Unfortunately for the Russians, Admiral Togo had correctly guessed his intentions and based virtually the entirety of the Japanese surface fleet at Masan Bay, on the coast of Korea, where - like a spider waiting in the corner of a web - it could quickly sortie for action when the Russians entered the strait.

Togo’s decision to bet the farm on Tsushima spoke to extreme confidence and calm. Although the Japanese had virtually all the momentum in the war, there were larger strategic reasons to be nervous. The Japanese victory at Mukden had required committing virtually all of Japan’s trained reserves, and the country was generally running low on both manpower and cash (in fact, Japan’s looming exhaustion was the primary reason why the terms of the eventual peace were much less decisive than expected, given the scope of their victories). The Russian Army in Manchuria, although defeated, had been able to withdraw in good order to the north and was awaiting reinforcement. More generally, although the Japanese had won significant victories, they had no ability to defeat Russia strategically, given the scope of Russian manpower and their strategic depth. If Togo gambled wrong - if the Russians went east, around Japan, and evaded him - the war threatened to extend for another year, and the longer this war went on the better it was for Russia.

But Togo had not gambled wrongly. As the Japanese waited for weeks at Masan, waiting for some clue as to Rozhdestvensky’s whereabouts, there was increasing chatter that the Japanese fleet ought to redeploy northward and hedge its bets. Togo decided to wait. On the 27th, he received a vital bit of information that confirmed he had been correct. Intelligence arrived informing Togo that much of the Russian support fleet, including the colliers, had broken off from the battle fleet and arrived in Shanghai. This confirmed Togo’s bet on Tsushima: if the Russians were planning to take the longer route and sail to the east of Japan, they would have kept the supporting ships with them. At 2:45 AM on May 27th, the Japanese reconnaissance cruiser Shinano Maru managed to spot the Russian fleet, despite the foggy night. A radio message came crackling into Togo’s anchorage at Masan:

The enemy sighted in number 203 section. He seems to be sterring for the eastern channel.

By 6:30 AM, the Japanese fleet had spilled out of Masan Bay and was steaming into Tsushima to intercept the enemy. Togo’s flagship, the battleship Mikasa, hoisted a signal strongly evocative of Nelson’s famous exhortations:

The fate of the Empire depends on today’s result, let every man do his utmost.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.