Total Kievan Debellation

The Russo-Ukrainian War: Year 3

On March 5, 2022, the wreck of the sailing ship Endurance was found in the depths of the Weddell Sea off the coast of Antarctica. This, of course, was the vessel lost in Ernest Shackelton’s third expedition to Antarctica, which became trapped in the ice and sank in 1915. The story of that expedition is an extraordinary tale of human fortitude - with the Endurance lost to the ice, Shackleton’s crew evacuated to a loose ice flow where they camped for nearly 500 days, drifting about the Antarctic seas, before making a desperate dash across the open ocean in an open 20 foot lifeboat, finally reaching the southern shore of inhospitable and mountainous South Georgia Island, which they then had to cross on foot to reach the safety of a whaling station.

The story itself has an essentially mythic quality to it, with Shackleton’s crew surviving for years on free floating ice floes in the most inhospitable seas on earth. For our purposes, however, it is the story’s coda that is particularly interesting. In Shackleton’s memoirs, he remembered that, upon finally reaching the safety of the Stromness whaling station, one of his first questions was about the war in Europe. When Shackleton first set out on his ill-fated expedition on August 8, 1914, the First World War was less than a week old, and the German Army had just begun its invasion of Belgium. There was little expectation then that the war would proceed as it did, unleashing four years of slaughterous positional warfare that engulfed the continent.

Shackleton, having been adrift at sea for years, clearly did not imagine that the war could still be raging, and asked the commandant of the whaling station “tell me, when was the war over?”

The answer came back: “The war is not over. Millions are being killed. Europe is mad. The world is mad.”

The timing is serendipitous, since the discovery of the Endurance’s wreck, after more than a hundred years, happened to occur only a few weeks after the world again went mad, with the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War in February 2022. As time continues its inexorable march and the calendar turns yet again, the war is passing through its third full winter. In February, Z-World will be three years old.

Of course, modern communications make it extremely unlikely that anybody could be cut fully out of the loop for years at a time, like Shackleton and his men. Instead of being ignorant as to whether or not the war is over, many of us are exposed on a daily basis to footage of men being killed, buildings being blown up, and vehicles being shredded. Twitter has made it essentially impossible to live under a rock, or on an ice floe, as it were.

If anything, we have the very opposite problem of Shackleton - at least as far as our wartime information infrastructure goes. We are saturated in information, with daily updates tracking advances of a few dozen meters and never ending bombast about new game changing weapons (which seem to change very little), and bluster about “red lines”. This war seems to have an unyielding dynamic on the ground, and no matter how many grand pronouncements we hear that one side or the other is on the verge of collapse, the sprawling front continues to grind up bodies and congeal with bloody positional fighting.

It would seem difficult to believe that a high intensity ground war in Europe with hundreds of miles worth of front could be boring, yet the static and repetitive nature of the conflict is struggling to hold the attention of foreign observers who have little immediately at stake.

My intention here is a radical zoom-out from these demoralizing and fatiguing small scale updates (as valuable as the work of the war mappers is), and consider the aggregate of 2024 - arguing that this year was, in fact, very consequential. Taken as a whole, three very important things happened in 2024 which create a very dismal outlook for Ukraine and the AFU in the new year. More specifically, 2024 brought three important strategic developments:

Russian victory in southern Donetsk which destroyed the AFU’s position on one of the war’s key strategic axes.

The expenditure of carefully husbanded Ukrainian resources on a failed offensive towards Kursk, which accelerated the attrition of critical Ukrainian maneuver assets and substantially dampened their prospects in the Donbas.

The exhaustion of Ukraine’s ability to escalate vis a vis new strike systems from NATO - more broadly, the west has largely run out of options to upgrade Ukrainian capabilities, and the much vaunted delivery of longer range strike systems failed to alter the trajectory of the war on the ground.

Taken together, 2024 revealed a Ukrainian military that is increasingly stretched to the limits, to the point where the Russians were able to largely scratch off an entire sector of front. People continue to wonder where and when the Ukrainian front might begin to break down - I would argue that it *did* break down in the south over the last few months, and 2025 begins with strong Russian momentum that the AFU will be hard pressed to arrest.

Front Collapse in South Donetsk

What stands out immediately about the operational developments in 2024 is the marked shift of energies away from the axes of combat that had seen the most intense fighting in the first two years of the war. In a sense, this war has seen each of its fronts activate in a sequence, one after the other.

After the opening Russian offensive, which boasted as its signature success the capture of the Azov coastline and the linkup of Donetsk and Crimea, the action shifted to the northern front (the Lugansk-Kharkov axis), with Russia fighting a summer offensive which captured Severodonetsk and Lysychansk. This was followed by a pair of Ukrainian counteroffensives in the fall, with a thrust out of Kharkov which pushed the front back over the Oskil, and an operation directed at Kherson which failed to breach Russian defenses but ultimately resulted in a Russian withdrawal in good order over the Dnieper due to concerns over logistical connectivity and an over-extended front. Energies then pivoted yet again to the Central Donbas axis, with the enormous battle around Bakhmut raging through the spring of 2023. This was followed by the failed Ukrainian offensive on Russia’s defenses in Zaporozhia, in the south.

Just to briefly recapitulate this, we can enumerate several operational phases in the first two years of the war, occuring in sequence and each with a center of gravity in different parts of the front:

A Russian offensive across the land bridge, culminating in the capture of Mariupol. (Winter-Spring 2022, Southern Front)

A Russian offensive in Lugansk, capturing Severodonetsk and Lysychansk. (Summer 2022, Donets-Oskil front)

Ukrainian Counteroffensives towards the Oskil and Kherson (Autumn 2022, Oskil and Dnieper fronts)

The Russian assault on Bakhmut (Winter-Spring 2023, Central Front)

Ukrainian counteroffensive on the land bridge (Summer 2023)

Amid all of this, the front that saw the least movement was the southeastern corner of the front, around Donetsk. This was somewhat peculiar. Donetsk is the urban heart of the Donbas - a vast and populous industrial city at the center of a sprawling conurbation, once home to some 2 million people. Even if Russia succeeds in capturing the city of Zaporizhia, Donetsk will be by far the most populous of Ukraine’s former cities to come under Moscow’s control.

In 2014, with the outbreak of the proto-Donbas war, Donetsk was the locus of much of the fighting, with the airport on the city’s northern approach the scene of particularly intense combat. This made it rather strange, then, that at the start of 2024 the Ukrainian Army continued to occupy many of the same positions that they built a decade prior. As intense fighting ebbed and flowed along other sectors of front, Donetsk remained besieged by a web of powerfully held Ukrainian defenses, anchored by heavily fortified urban areas stretching from Toretsk to Ugledar. Early Russian attempts to crack this iron ring open, including an assault on Ugledar in the winter of 2023, met with failure.

The signature operational development of 2024, then, was the re-activation of the Donetsk front, after years of static combat. It is not an exaggeration to say that after years of coagulation, the Russian Army cracked this front wide open in 2024 and Ukraine’s long and strongly held network of urban strongpoints collapsed.

The year began with the AFU fighting for its fortress in Avdiivka, where it continued to block the northern approach to Donetsk. At the time, the typical argument that one heard from the Ukrainian side was that the Russian assault on Avdiivka was pyrrhic - that the Russians were capturing the city with exorbitantly costly “meat assaults” that would inevitably sap Russian combat power and exhaust their ability to continue the offensive.

With the full measure of the year behind us, we can definitively say that this is not the case. After the fall of Avdiivka, Russian momentum never seriously slackened, and in fact it was the AFU that appeared to be increasingly exhausted. The Ukrainian breakwater position at Ocheretyne (which had previously been their staging point for counterattacks around Avdiivka) was overrun in a matter of days, and by the early summer the frontline had been pushed out towards the approach to Pokrovsk.

The Russian thrust towards Pokrovsk led many to believe that this city was itself the object of Russian energies, but this was a misread of the operational design. Russia did not need to capture Pokrovsk in 2024 to render it sterile as a logistical hub. Simply by advancing towards the E50 highway, Russian forces were able to cut off Pokrovsk from Ukrainian positions to the south on the Donetsk front, and Pokvrovsk is now a frontline city subject to the full spectrum of overwatch from Russian drones and tube artillery.

By autumn, the Russian advance had put the Ukrainians in a severe salient, creating an unstable chain of positions in Selydove, Kurakhove, Ugledar, and Krasnogorivka. Russia’s advance from Ocheretyne onto the southern approach to Pokrovsk acted like an enormous scythe, isolating the entire southeastern sector of the front and allowing Russian forces to carve through it in the closing months of the year.

This war has turned the word “collapse” into a devalued buzzword. We are told repeatedly that one side or the other is on the verge of collapse: sanctions will “collapse” the Russian economy, the Wagner uprising of 2023 proved that the Russian political system was “collapsing”, and of course we hear that exorbitant losses have one army or the other on the verge of total failure - which army that may be depends on who you ask.

I would argue, however, that what we saw from October 2024 onward represents a real occurrence of this oft-repeated and discarded word. The AFU suffered a genuine collapse of the southeastern front, with the forces positioned in their strongpoints too attrited and isolated to make a determined defense, Russian fires becoming too heavily concentrated in ever more compressed areas to endure, and no mechanized reserve in the theater available to counterattack or relieve the incessant Russian pressure.

Ukraine does maintain enough drones and concentrated fires to limit a full Russian exploitation - that is, Russia is still not able to maneuver at depth. This gave the Russian advance a particular stop-start quality, leapfrogging from one settlement and fortress to the other. More generally, Russia’s preference to use dispersed small-unit assaults limits the potential for exploitation. We have to emphasize, however, that Russian momentum on this axis has never seriously slackened since October, and many of the key Ukrainian positions were overrun or abandoned very quickly.

Ugledar is a good example: the Russians began their final push toward the town on September 24. By September 29, the 72nd Mechanized Brigade began evacuating. By October 1, Ugledar was fully under Russian control. This was a keystone Ukrainian position put in a completely untenable position and it went down in a week. One could argue, of course, that Ugledar held out for years (how then can we say with a straight face that it was captured in a week), but this is precisely the point. In early 2023 Ugledar (with the help of artillery stationed around Kurakhove) successfully repelled a multi-brigade Russian attack in months of heavy fighting. By October 2024, the position was completely untenable and was abandoned almost immediately when attacked.

The Ukrainians did no better trying to hold Kurakhove - previously a critical rear area that served as both a logistical hub and a base of fire for supporting (former) frontline strongpoints like Ugledar and Krasnogorivka. Kurakhove, now under full Russian control, will in turn serve as a base of support for the ongoing Russian push to the west towards Andriivka.

Taking the state of the front holistically, the AFU is currently holding two severe salients at the southernmost end of the line - one around Velyka Novosilka, and another around Andriivka. The former is likely to fall first, as the town has been fully isolated by Russian advances on the flanks. This is not a Bakhmut-like situation, where roads are described as “cut” because they are under Russian fire - in this case, all of the highways into Velyka Novosilka are cut by physical Russian blocking positions, making the loss of the position only a matter of waiting for the Russians to assault it. Further north, a more gentle and less strongly held salient exists between Grodivka and Toretsk. With Toretsk now in the final stages of capture (Ukrainian forces now hold only a small residential neighborhood on the city’s outskirts), the front should level here as well in the coming months.

This leaves the Russians more or less in full control of the approaches to Kostyantinivka and Pokrovsk, which are in many ways the penultimate Ukrainian held positions in Donetsk. Pokrovsk has already been bypassed several miles to the west, and the map portends a re-run of the typical Russian tactical methodology for assaulting urban areas - a methodical advance along the wings of the city to isolate it from arterial highways, followed by an attack on the city itself via several axes.

The coming months promise continued Russian advances across this front, in a continuation of what can only be regarded as the collapse of a critical front on the part of the AFU. The Russian Army is advancing to the western border of Donetsk oblast and will ferret the Ukrainians out of their remaining strongpoints at Velyka Novosilka and Andriivka, while pushing into the belly of Pokrovsk. At no point since the fall of Avdiivka have the Ukrainians demonstrated the ability to seriously stymie Russian momentum along this 75 mile front, and the ongoing dissipation of Ukrainian combat resources indicates that little will change in this regard in 2025.

Toehold: The Incredible Shrinking Kursk Salient

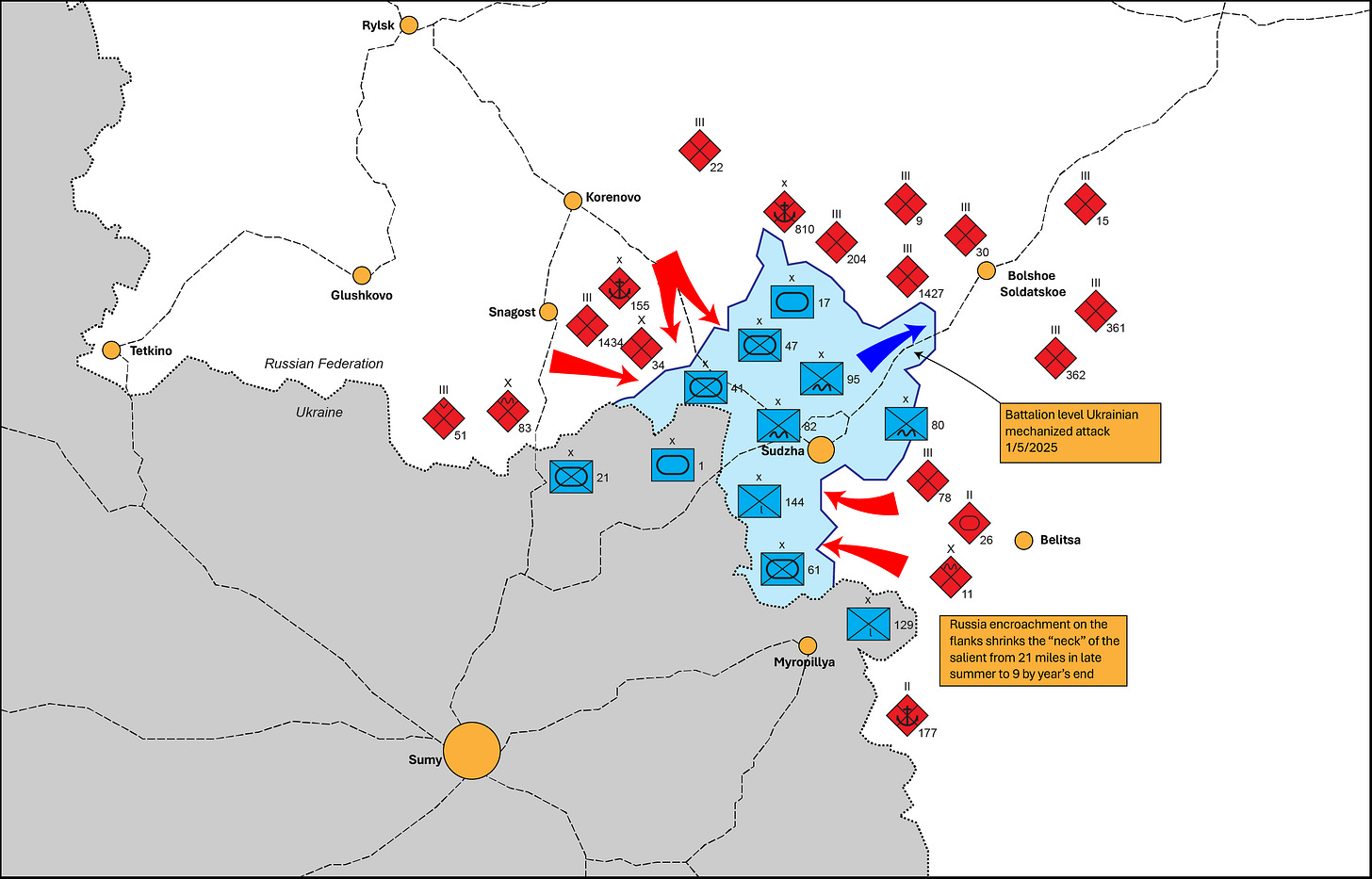

Throughout the autumn of 2024 and these early months of winter, as Ukrainian forces were dug out of their dense web of fortified positions in the southern Donbas, their comrades continued to stubbornly hold on to their position in Russia’s Kursk Oblast. The basic shape of Ukraine’s offensive into Kursk is by now well known - billed by Kiev as a gambit to change the psychological trajectory of the war and strike a prestige blow to Russia, the Ukrainian attack had early momentum after achieving initial strategic surprise, but quickly faltered after Ukrainian columns ran into effective Russian blocking positions on the highways out of Sudzha. Efforts to force the roads through Korenovo and Bolshoe Soldatskoe were defeated, and the Ukrainian grouping was left holding on to a modest salient around Sudzha, jutting out into Russia.

Throughout the autumn, Russian counterattacks have focused on chiseling away at the base of the Ukrainian salient - forcing the Ukrainians out of Snagost and pushing them away from Korenovo. The progress here has been incremental, but significant, and by the start of January the “neck” of the Ukrainian salient had been compressed down to a little over nine miles wide, after their initial penetration in the summer had forced a breach of over twenty miles. All told, Ukraine has lost about 50% of the territory that they grabbed in August.

The Russian pressure on the flanks of the salient have amplified many of the qualities that make this position wasteful and dangerous for the AFU. There is limited road connectivity for Ukrainian forces - a problem amplified by the rollback from Snagost, which cost them access to the highway running from Korenovo to Sumy. Apart from a few circuitous side roads, Ukrainian forces only have a single highway - the R200 route - to run material and reinforcements into the pocket, which allows Russian forces to surveil their lines of communication and conduct effective interdiction strikes. The compression of the pocket also greatly narrows the targeting area for Russian drones, tube artillery, and rocketry, and creates more condensed and saturating bombardment.

Despite the fact that this position has been profoundly unproductive for Ukraine - being steadily rolled back and having no synergy with other, more critical theaters - the same grouping of Ukrainian units remain here, fighting in a steadily more compressed space. Even more baffling, the Ukrainian grouping consists largely of premiere assets - Mechanized and Air Assault brigades - that could have contributed meaningfully as a reserve in the Donbas over the last three months.

On January 5, there was a surprise in the form of a renewed Ukrainian attack out of the salient. The internet of course jumped to the conclusion that the AFU was going back over to some sort of general offensive posture in Kursk, but the reality was very underwhelming - something like a battalion sized assault up the axis towards Bolshoe Soldaskoe, which got a few kilometers up the road before it ran out of steam. Ukrainian efforts to jam Russian drones were stymied by the increasing ubiquity of fiber-optic systems, and the Ukrainian attack collapsed within a day.

The tactical particulars of the Ukrainian attack are interesting, and there’s ongoing speculation as to its purpose - perhaps it was intended to cover a rotation or withdrawal, to improve tactical positions on the northern edge of the salient, or for inscrutable propaganda purposes. However, these specifics are rather unimportant: attacking out the end of the salient (that is, trying to deepen the penetration into Russia) does nothing to reverse Ukraine’s problems in Kursk. These problems are first, on the tactical level, that the salient has been greatly compressed on the flanks and continues to narrow, and on the strategic level the willful expenditure of valuable mechanized assets on a front that does not impact the critical theaters of the war. More simply, Kursk is a sideshow, and it is a sideshow that has gone wrong even within its own operational logic.

One thing that has been of endless interest, of course, have been the continued rumors of North Korean troops fighting in Kursk. Western intelligence agencies have been adamant about the presence of North Koreans in Kursk. Some people are predisposed to instinctively disbelieve everything that western officialdom says - while I think some skepticism is warranted, I do not automatically assume that they are lying. One recent report lays out what would seem to be a plausible version of this story: that the idea actually originated in Pyongyang, not Moscow, and that a modest number of Korean troops (perhaps 10,000) are embedded with Russian units. The presumption here is that the Koreans hatched the idea as a way to gain combat experience, with the Russians in turn getting auxiliary forces, though of questionable combat effectiveness.

However, it is worth noting that this is not nearly as important as it has been made out to be. Much has been made of the idea that the North Korean presence proves some sort of Russian state of desperation, but this is fairly silly on its face - with more than 1.5 million active personnel in the Russian military, 10,000 Korean troops in Kursk represents a paltry appendage. More importantly, there has been an attempt to portray the North Korean contingent as a major departure point in the war. In particular, the formulation “North Korean troops in Europe” has been used to conjure cold war imagery of communist despotism clawing at the free world.

The point, however, is that North Korean troops are presumed specifically to be in Kursk, which is in Russia. This is linked, of course, to the recently concluded mutual defense agreement signed between Moscow and Pyongyang. By attacking into Kursk - widening the front into prewar Russian territory - Ukraine created a defensive combat task for Russia which triggers the possibility of military assistance from North Korea. However much one may wish to link the Korean contingent to Russia’s dreaded “war of aggression”, the force in Kursk is very objectively engaged in the defense of Russian territory, and that makes it possible for Russia to use auxiliary forces - including conscripts and the troops of its allies - to fight there.

Ultimately, then, the presence of North Koreans in Kursk is interesting, but perhaps not very important after all. These troops are not in Ukraine (even under the most maximal definition of the Ukrainian territorial unit), they are not carrying the primary combat load, and they are unequivocally not the problem that the AFU is facing in Kursk. The “big problem” for Ukraine, very simply, is not the presence of some amorphous Korean horde dedicated to spreading Glorious Juche to Europe - it is the loitering of large grouping of their own precious mechanized brigades in a compressed salient, far far away from the Donbas, where they are greatly needed.

Scraping the Barrel: AFU Force Generation

I think it is well understood, of course, that Ukraine faces severe manpower constraints relative to Russia, both in terms of the raw totals of male biomass available - with roughly 35 million fighting aged males in Russia against perhaps 9 million in prewar Ukraine - but also in terms of its capacity to mobilize them.

Ukraine’s mobilization scheme is hampered by both widespread draft evasion (with willingness to serve decreasing as the war has stretched on) and a stubborn unwillingness to draft younger men, aged 18-25. Ukraine is structurally burdened with a deeply imbalanced population structure: there are roughly 60% more Ukrainian men in their 30’s than in their 20’s. Given the relative scarcity of young men, particularly in their early 20's, the Ukrainian government rightly views this 18-25 year old cohort as a premium demographic cohort that it is loathe to burn away in combat. Given the ubiquity of draft evasion, the refusal to mobilize younger males, and the corruption and inefficiency characteristic of the Ukrainian government, it should come as no surprise when Ukrainian mobilization falters.

Russia, in contrast, has both a much larger pool of potential recruits and a more efficient apparatus for mobilization. In contrast to Ukraine’s scheme of compulsory conscription, Russia has relied on generous sign-on bonuses to solicit volunteers. Russia’s incentive system, to this point, has provided a steady stream of enlistments that has been more than enough to offset Russian losses. Without going too far into the various speculative estimates of Russian casualties, it is widely acknowledged by western military leadership that Russia has significantly more personnel now than it did at the start of the war.

All of that is to say: Ukraine faces a severe structural disadvantage in military manpower in the aggregate, which is exacerbated by the idiosyncrasies of the Ukrainian mobilization law, ameliorated slightly by the relatively low troop densities and the preponderant power of strike systems in this war.

The argument that I want to make here, however, is that Ukraine’s systemic problems matching Russian manpower have been exacerbated by several developments which specifically became prominent in 2024. In other words, 2024 can and should be marked as the year where Ukrainian manpower constraints became markedly and perhaps irretrievably worse due to specific decisions made in Kiev, and particular developments on the ground.

These are as follows:

The decision to expand the AFU’s force structure through the creation of the “15 series” brigades

The decision to deliberately widen the front and create additional demands for manpower by launching the incursion into Kursk

The stall out of Ukraine’s new mobilization program in the autumn

Accelerating problems with desertion in the AFU

We’ll run through these in order.

An army that is intaking new personnel has to decide between two possible allocations for them. New personnel can be used as replacements to replenish existing frontline units, or they can be used to expand the force structure by creating new units. That much seems fairly obvious, and ideally mobilization will exceed losses and make it possible to do both. Where armies face hard manpower constraints, however - that is, where losses are equal to or greater than intake of men, the decision to expand the force structure can have monumental consequences. The stereotypical example, of course, would be the late-war Wehrmacht, which created premiere new assets in the form of Waffen SS divisions, which received privileged access to recruits and equipment while regular army divisions in the line suffered from a trickle of replacements which could not keep up with losses.

Ukraine, with its garbled force structure, has created a mess through its own attempts to expand its force structure in the face of dwindling strength on the line. Late in 2023, the AFU announced intentions to form an entirely new grouping of brigades - the so-called “15 series”, given their designations as the 150th, 151st, 152nd, 153rd, and 154th Mechanized Brigades. This was followed in 2024 with the appending of the 155th Mechanized Brigade, which was to be trained and equipped in France.

Forming a new grouping of mechanized brigades is essential to the way that Ukraine is presenting its war. Because Ukraine still aims (at least on paper) to recapture all of its Russian held territory, there must always be the illusory possibility of a future offensive, and in order for that illusory possibility to remain, Ukraine must present itself as actively preparing for future offensive operations. Ukraine’s presentation of its own strategic animus - the idea that it is holding the front while it prepares to go back on the offensive - essentially locks it into a program of expanding its force structure.

The problem for Ukraine is that the immense pressure on the front makes it essentially impossible for them to properly husband resources the way they would like. Properly training and equipping half a dozen fresh mechanized brigades and holding them in reserve would be very helpful, but they cannot really do this in light of the demands for personnel at the front. These brigades instead become “paper formations” that have a bureaucratic existence, while their organic assets are pulled apart and sucked into the front - stripped down into battalion or company sized elements that can be plugged into sectors of need on the frontline. At the moment, none of the 15 series brigades have seen action as organic units - that is, fighting as themselves.

The French-trained 155th brigade forms a useful example. Originally designed as an overweight formation of some 5800 men, equipped with premiere European equipment, the brigade was hemorrhaging personnel from the start, with Ukrainian sources reporting that some 1700 men - many of them forcibly conscripted off the streets of Ukraine - deserted the unit during training and formation. A collapse in the brigade’s leadership - with its commander resigning - made matters even more complicated, and the formation’s first action around Pokrovsk went badly. Now, the brigade is being dismembered, if not formally disbanded, with personnel and vehicles being stripped down and parceled out to bolster neighbor units.

The decision to allocate personnel to new mechanized brigades (though given stocks of armored vehicles it is questionable whether those designations mean anything) does not necessarily change Ukraine’s manpower balance in the aggregate, but it is certainly an inefficient way to use personnel. To return again to the 155th brigade, one problem noted by Ukrainian analysts was the fact that much of the brigade was formed whole cloth from forcibly mobilized personnel, without a proper cadre of veterans and experienced NCOs - some 75% of the brigade, it turns out, had been mobilized less than two months before arriving in France for training. This fact was certainly instrumental in the mass desertions and the brigade’s poor combat effectiveness.

Given Ukraine's constraints, the best course of action would undoubtedly be to allocate new personnel and equipment as replacements to build out the depleted veteran brigades on the front lines, plugging in replacements around existing veterans and officers. Kiev, however, prizes the prestige that comes from force expansion and the “shiny new toy” factor of new formations equipped with scarce and valuable equipment like Leopard tanks. These new brigades, though billed as premiere assets, clearly have lower combat effectiveness than existing formations, given their lack of experience, shortage of veteran officers, and low unit cohesion.

The simple reality, however, is that replacements for existing brigades are nowhere close to keeping up with burn rates. Frontline units have complained of increasingly dire infantry shortages for months, with some brigades on the Pokrovsk axis reporting that they are down to less than 40% of their allocated infantry complements.

In short, Ukraine’s decision to embark on force expansion in the face of significant manpower shortages has exacerbated the problem - both starving veteran units of replacements and concentrating newly mobilized personnel into combat ineffective formations that lack a veteran core, experienced officers, and vital equipment. They have tried, belatedly, to square this circle by parceling out new formations to backstop line brigades, but this is less than ideal - it leads to a patchwork order of battle with lower unit cohesion and a fragmented defense.

Unfortunately, this comes precisely as Ukraine has created additional self-imposed strains on its resources, in particular through its incursion into Kursk. At the moment, elements of at least seven mechanized brigades, two marine infantry brigades, and three air assault brigades are stationed on the Kursk axis. Without going too far into the weeds rehashing Ukraine’s operation here, it’s important to remember that Ukraine - facing extreme pressures on its force generation - voluntarily chose to widen the front into a secondary theater, diverting scarce assets and reducing its own ability to economize forces.

In summary, Ukraine has made deliberate decisions to widen the front and expand its force structure, both of which have been decidedly detrimental to its efforts to economize personnel. This comes precisely as a 2024 effort to ramp up mobilization has come off the rails.

Ukraine’s mobilization program suffered from a variety of defects, including gaps and errors in its databases and endemic corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency. Laws passed in 2024 aimed to rectify many of these problems, including through the rollout of an app that would allow draft-eligible men to register and check their status without having to visit recruitment offices. It appeared that matters had come to a head when Zelensky fired several recruitment chiefs in 2023, and there was a real sense of urgency. After some signs of initial promise, it is clear that this intensified mobilization drive has faltered over the autumn and early winter.

There were initially signs of optimism for Ukraine - in the first month after the new mobilization law was passed, there was a surge and the army enlisted 30,000 new personnel. However, by the end of the summer this initial burst of enlistments had faded, and mobilization was again running behind the AFU’s losses. An October briefing from the Ukrainian General Staff confirmed that enlistments had already declined by 40% after the brief surge brought on by the new mobilization law. Around the same time, officials in Odessa (Ukraine’s third largest city) admitted that they were running at only 20% of their mobilization quota.

The problems are myriad. The new mobilization law led to some initial improvements but has ultimately failed to resolve problems with draft evasion, bureaucratic miscues remain endemic, and employers desperate to retain workers filed an avalanche of employment related draft deferments. Unable to sustain the initial surge of enlistments, Ukraine faces a looming manpower crisis.

Furthermore, Ukraine’s continued inability to provide either demobilization or timely rotations means that mobilized personnel face the prospect of indefinite service on the frontlines. This is obviously bad for morale, with soldiers contemplating the possibility of years of uninterrupted service, and this in turn drives the desertions that are becoming a mounting problem for the AFU. Some reports indicate that as many as 100,000 Ukrainian troops have deserted by this point, many no doubt driven by the psychological and physical strains of endless combat with no prospect of rotation.

A deadly feedback loop is now at work, with the lack of rotations and the shortage of replacements synergizing to accelerate the burn of Ukrainian personnel. The AFU is unable to regularly rotate units out of combat, and the inadequate flow of replacements causes frontline infantry complements to wear thin. Unable to rotate or reinforce, line brigades resort to cannibalization - scraping support personnel like mortar teams, drivers, and drone operators to fill out frontline positions. This further accelerates losses as brigades fight with thinned out support and fires elements, and makes Ukrainian men more unwilling to enlist - because there is now no guarantee that becoming a drone operator, for example, will save one from being sent to a frontline trench eventually.

Where does this leave us? Ukraine continues to dispose of a very large force, with more than a hundred brigades and hundreds of thousands of men under arms. This force, however, is both substantially outnumbered by the Russian army and in a clear trend of decay. Despite a highly touted attempt to reinvigorate the mobilization apparatus in 2024, the intake of new personnel is clearly too low to offset losses, and the heavy lifting formations in critical sectors of front have seen their strength - particularly in the infantry complements - decline, in some cases to critical levels.

The failure of Ukraine’s 2024 mobilization program has coincided with several strategic choices which have exacerbated manpower concerns - specifically the decision to embark on a program of force expansion even as the AFU voluntarily extended its commitments by opening a new secondary front in Kursk. In other words, Ukraine’s mobilization falls short of its force requirements, and the AFU has also made choices that sabotaged its ability to economize. Units are ground up, replacements come in a paltry trickle, rotations are late or absent, units cannibalize themselves, and angry and weary men desert.

It’s not at all clear that this will lead to a “breaking point”, in the sense that people are anticipating. Ukrainian strike capabilities and the Russian preference for dispersed, leapfrogging assaults limit the potential for grand breakthroughs and exploitation. However, what we saw over the past three months on the southern Donetsk axis offers a preview of what awaits: an exhausted force being steadily rolled back, dug out of its strongpoints, and mauled - covering its retreat with drones but losing position after position. The line holds, until it doesn’t.

End of the Line: ATACMs, JASSMs, and Hazelnuts

Ukraine’s ability to remain in the field depends on a titration of two indispensable resources: first, Ukrainian male biomass, and secondly the critical western weaponry that gives them combat effectiveness. We have evaluated the first: Ukraine is not exactly out of men, but the trends of its mobilization program are poor and personnel shortages are mounting. The trends regarding the second are, if anything, even more foreboding for Kiev.

There are two general dynamics that have emerged, neither of which create an optimistic picture for Ukraine, which we’ll examine in turn. These are as follows:

The delivery of heavy weaponry to Ukraine (tanks, IFVs, and artillery tubes) has largely dried up in recent months.

The west has essentially run out of escalatory weaponry (strike systems) to give, and those systems already given have failed to meaningfully altar the trajectory of the war.

In 2023, building out new mechanized units was the name of the game, with the Pentagon leading a multinational effort to stand up an entire army corps worth of units equipped with Leopards, Challengers, and a whole slew of western IFVs and APCs. When that lovingly assembled grouping bashed its head on a rock in the botched assault on the Zaporizhia line, the United States belatedly and begrudgingly dispatched its own Abrams to backstop the Ukrainian tank force. In 2024, however, deliveries of heavy weapons slowed to a trickle.

The role of the tank in Ukraine has been greatly misunderstood. The vulnerability of tanks to the myriad strike systems of the modern battlefield led some observers to declare that the tank as a weapons system was now obsolete, but this did not really square with the fact that both combatants in this war were eager to deploy as many as possible. Tanks need more critical enablers - more combat engineering, air defense, and electronic warfare support - but they continue to fill an indispensable role and remain an essential item in this war. The failure of Ukraine’s 2023 counteroffensive showed, if anything, that tanks simply are not “game changing” systems, but mass consumption items - but this has always been the case. The signature quality of iconic tanks like the Sherman and the T34 was that they were numerous.

Unfortunately for Ukraine, deliveries of tanks have dropped off dramatically after the failures of 2023. America’s drawdowns for Ukraine in 2024 were almost entirely devoid of armored vehicles of any kind. Data from the Kiel Institute, which has been meticulous tracking weaponry commitments and deliveries, confirms a sharp dropoff in heavy weapons in 2024. In 2023, Ukraine’s backers pledged 384 tanks. This dropped to just 98 in 2024 - which explains why the new Ukrainian mechanized brigades are perilously light on the equipment indicative of their designations.

While 2023 was all about building out Ukraine’s mechanized package with tanks, IFVs, and engineering, 2024 has been largely about enhancing Ukraine’s strike capabilities. There have been two separate elements at play - first, the delivery of both air and ground launched systems (most notably the British Storm Shadows and American ATACMs respectively), and secondly the loosening of the rules of engagement to allow Ukraine to strike targets inside pre-war Russia.

This dovetailed, as it turned out, with Ukraine’s operation in Kursk, and in many ways the most direct impact of the Kursk incursion has been to force the west’s hand on the rules of engagement. While Ukraine has long been striking inside Russia with indigenous systems, most notably drones, the White House continued to drag its feet on formal approval for strikes with American systems. By launching a ground assault on Kursk, Ukraine made the decision for them: the United States gave clearance to use ATACMs to support the ground forces in Kursk, and this metastasized into general license to strike Russia with the full range of available systems. This was a poignant reminder that, however we conceive of the proxy-sponsor relationship, Ukraine has some ability to force America’s hand: a classic example of the tail wagging the dog.

In any case, 2024 saw Ukraine and its western backers slowly but surely bash through all the supposed red-lines in this domain: the British breached first with the delivery of Storm Shadows late in 2023, and this was followed by the delivery of ATACMs (with a handful of F16’s to boot), and finally the loosening of the rules of engagement to clear strikes on Russia.

Where does this leave us? There would seem to be three important things to consider.

The west has essentially reached the end of its escalation chain. The only remaining step that they can take would be to supply Ukraine with JASSMs (Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile), which would mark a quantitative but not a meaningful qualitative upgrade to Ukraine’s strike capabilities.

Ukraine’s use of western-supplied strike assets has been dissipated and has not materially improved their situation on the ground.

Russia maintains a dominant strike advantage, both qualitative and quantitative.

Ukraine faces a stark disadvantage in strike capability relative to Russia, in a variety of ways. Russian strike assets are far more numerous and have significant range advantages, but it is also important to take into consideration both Russia’s significantly greater strategic depth and its more dense and relatively unscathed air defense. Unlike Ukraine, which has seen its air defense stretch to the limit with destroyed launchers and a mounting interceptor shortage, Russia’s air defenses have been essentially untouched, as Ukraine has lacked the large numbers of assets required to conduct a proper SEAD/DEAD (Suppression/Destruction of Enemy Air Defense) campaign.

Given this basic calculus, using western strike systems to wage a blow for blow strategic air campaign is bad math for Ukraine. It is generally unwise to engage in a bat fight when your opponent is a bigger man with a much longer bat. Instead, Ukraine’s strike systems should have been leveraged to support ground operations - concentrating strikes spatially and in time to synergize with efforts on the ground. Just as a simple thought experiment, it is not difficult to imagine ATACMs making a difference if they had been available in 2023 and used to saturate Russian rear areas during the assault on the Zaporizhia line - striking in tempo with the mechanized assault to disrupt Russian command and control and prevent reinforcement of critical areas.

Instead, Ukraine’s strike capacity has been largely dissipated in attacks that sometimes achieve success hitting Russian installations but fail to directly support successful operations on the ground. The result is a diffusion of Ukrainian striking power that is less than the sum of its parts. Now, Ukraine has essentially run dry on missiles - of the 500 ATACMs sent by the United States, perhaps 50 are left in Kiev’s stockpiles. Stocks of air launched Storm Shadow missiles are similarly low, and Britain’s commitment to resupply is limited to “a few dozen”.

The last option for the west to backstop Ukrainian strike capability are American JASSMs. While there is a longer-range variant in production (the JASSM-ER, or Extended Range), these are relatively new and expensive and are earmarked for American stocks - it is therefore presumed that the Ukrainians would receive the standard variant. The standard JASSM has slight range advantages over Storm Shadows and ATACMs, at roughly 230 miles. In the event that JASSMs are not given, there is a shorter range system called the SLAM (Standoff Land Attack Missile) with a range of some 170 miles. Both JASSMs and SLAMs would be compatible with Ukrainian F-16s.

Two things need to be noted about the JASSM. First, the JASSM - while offering slightly longer ranges - would essentially serve as a backstop/replacement for the rapidly dwindling ATACMs and particularly the air launched Storm Shadows - instead of Ukraine’s native SU-24s launching Storm Shadows, they would utilize F-16s launching JASSMs. This would not represent a dramatic upgrade in Ukrainian capabilities, but would instead simply serve to maintain a bare minimum Ukrainian strike capability. JASSMs are a replacement for dwindling capabilities, not an augmentation to them.

Secondly, it must be understood that JASSMs are the last stop. We’re now entering the territory, not of artificially constructed red lines, but physical and real limits. Russia has essentially eaten the gifted stocks of ATACMs and Storm Shadows, with little discernable effect on their ability to fight, and JASSMs are the last extant item in the inventories to keep Ukrainian strike capabilities operative. We are at the last rung of the aid ladder.

In the case of JASSMs, however, there are notable downsides for the United States. This is an important case of putting all of one’s eggs in the same technological basket. In 2020, the United States scrapped the development of its conventionally armed Long Range Standoff Missile, making the JASSM - particularly the new extended range variants - the system for the United States, earmarked to play a critical role in future conflicts, particularly in the Pacific. This makes the JASSM an extremely sensitive system, as a centerpiece of American strike capabilities, particularly with the modernization of the Tomahawk system crawling along at a few dozen units per year.

Given the fact that JASSMs are GPS guided, there are real reasons to be reticent about giving Ukraine such a technologically sensitive system. Russian electronic warfare has enjoyed considerable success jamming GPS and disrupting similarly guided American systems. Allowing the Russians to gain familiarity with a keystone American system could wreak havoc on Pentagon war planning - most, if not all of the strike eggs are in this basket, so why let an adversary peek inside?

It’s probable, given what we have seen to this point, that these concerns will ultimately be dismissed and Ukraine will receive a line of JASSMs which will backstop their strike capabilities - but given the size of Ukraine’s F-16 fleet, the scale will be constrained. Furthermore, air launched systems are less optimal for Ukraine, given their dependence on large and easily targeted airfields, in contrast to ground launched systems which are mobile and more easily concealed.

Certainly, JASSMs will never give Ukraine the ability to match Russia’s own strike capacity. After hearing endlessly about how Russia is running out of missiles, it has at last been concluded that this is simply not true, and indeed never was. Recently, Ukrainian defense intelligence admitted that per their own estimates Russia retains about 1,400 long range missiles in its reserves, with a monthly production of roughly 150 units. Russian production of inexpensive Geran drones has also skyrocketed, with Ukrainian intelligence estimating a ceiling as high as 2,000 drones per month.

There is also the matter of the new Russian missile system - the now famous Oreshnik, or Hazel Tree. Russia tested the Oreshnik system on a large machining plant in Dnipro on November 21, 2024, which allowed the basic capabilities of the system to be gauged. The Oreshnik is an Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile, characterized by its hypersonic capabilities (exceeding Mach-10) and its Multiple Independent Reentry Vehicle equipped with six separate warheads, with the potential for submunitions in each. Although the attack on Dnipro was essentially a demonstration which used inert training warheads (that is, without explosive payloads), the missile can be configured with nuclear or conventional warheads.

As in the case of the North Korean troops in Kursk, I rather think that the Oreshnik launch was not nearly as important as it was made out to be. The system is expensive and likely impractical for conventional use. I understand the desire to conceive of Oreshnik as a massively powerful conventional weapon - showering its target with half a dozen warheads with the power of an entire flight of Kalibr missiles - but there are several problems with this. The accuracy of the system (the CEP, or “Circular Error Probable” in the technical parlance) is much more consistent with a nuclear delivery system than a conventional one. Furthermore, the problem with using an IRBM for conventional strikes is the danger of miscalculation - foreign adversaries may misinterpret the launch as a nuclear attack and respond appropriately. This is precisely why the Russian government actually alerted the United States to the launch ahead of time - a fine arrangement for a demonstration, but impractical for a weapon that is intended to be used regularly.

We may see another use of the Oreshnik against Ukraine, but ultimately this is unlikely to be a system of consequence in this war. The demonstration in Dnipro was instead likely intended to send a message to Europe - reminding NATO that Russia has the capacity to deliver strikes against European targets that cannot be intercepted. It also serves as a poignant reminder that Europe lacks the equivalent capability, and in essence provides a demonstration of Russia’s ability to launch missiles from far beyond the range of either Ukrainian or European response. The Hazelnut is a tangible reminder of Russia’s strategic depth and strike dominance in Ukraine.

Ultimately, Ukraine will lose the strike game. It’s strike capacity has dwindled, with missiles frittered away in a dissipated air campaign, and though the exhaustion of Storm Shadow and ATACMs stocks can be offset somewhat by JASSMs, Ukraine simply lacks the range or quantities necessary to match Russian capabilities. Needing to do more with less, Ukraine instead diffused its assets and failed to synergize its strikes with ground operations. We are now at the end of the line - after JASSMs, there’s nothing left in western warehouses to upgrade Ukrainian capabilities. Hazelnuts or no, the math on this bat fight is bad for Kiev.

Conclusion: Debellation

Trapped in an endless news cycle, with daily footage of FPV strikes and exploding vehicles, and a dutiful cottage industry of war mappers alerting us to every 100 meter advance, it can easily feel like the Russo-Ukrainian War is trapped in an interminable doom loop which will never end - Mad Max meets Groundhog Day.

What I have endeavored to do here, however, is argue that 2024 actually saw several very important developments which make the coming shape of the war relatively clear. To briefly recapitulate:

Russian forces caved in Ukrainian defenses at depth across an entire critical axis of front. After remaining static for years, Ukraine’s position in Southern Donetsk has been obliterated, with Russian forces advancing through an entire belt of fortified positions, pushing the front into Pokrovsk and Kostayantinivka.

The main Ukrainian gambit on the ground (the incursion into Kursk) failed spectacularly, with the salient being progressively caved in. An entire grouping of critical mechanized formations wasted much of the year fighting on this unproductive and secondary front, leaving Ukrainian positions in the Donbas increasingly threadbare and bereft of reserves.

An attempt by the Ukrainian government to reinvigorate its mobilization program failed, with enlistments quickly trailing off. Decisions to expand the force structure exacerbated the shortage of manpower, and as a result the decay of Ukraine’s frontline brigades has accelerated.

Long awaited western upgrades to Ukraine’s strike capabilities failed to defeat Russian momentum, and stocks of ATACMs and Storm Shadows are nearly exhausted. There are now few options remaining to prop up Ukrainian strike capacity, and no prospect of Ukraine gaining dominance in this dimension of the war.

In short, Ukraine is on the path to debellation - defeat through the total exhaustion of its capacity to resist. They are not exactly out of men and vehicles and missiles, but these lines are all pointing downward. A strategic Ukrainian defeat - once unthinkable to the western foreign policy apparatus and commentariat - is now on the table. Quite interestingly, now that Donald Trump is about to return to the White House, it is suddenly acceptable to speak of Ukrainian defeat. Robert Kagan - a stalwart champion of Ukraine if there ever was one - now says the quiet part out loud:

Ukraine will likely lose the war within the next 12 to 18 months. Ukraine will not lose in a nice, negotiated way, with vital territories sacrificed but an independent Ukraine kept alive, sovereign, and protected by Western security guarantees. It faces instead a complete defeat, a loss of sovereignty, and full Russian control.

Indeed.

None of this should be particularly surprising. If anything, it is shocking that my position - that Russia is essentially a very powerful country that was very unlikely to lose a war (which it perceives as existential) right in its own belly - somehow became controversial or fringe. But here we are.

Carthago delenda est

I hope Kagan is right about that! What infuriates me is Zelensky's portray of the Ukraine as the victim. The Ukraine is like a neighbour who invites your worst enemy into his house in order to threaten you. This is hardly a country just minding its own business. What guarantees can the squirrel get that it can punch the bear on the nose and not get a response? The only real guarantee is for the squirrel not to do that - but Z. refuses to learn.

A good big picture summary, and in line with my own thinking so naturally I like it...

We can absorb a lot of daily detail, but the wider view is more important.

My sense last year was that the UAF would "collapse" in the fall. Well that did not occur, but it has increasingly been unable to effectively resist and hold ground. I think the collapse will be like bankruptcy, very slowly at first then all at once. Once the prospect of defeat takes hold, I suspect the PBI in the UAF will find reasons not to fight. I've commented elsewhere that Mr T should cut and run on day 1 as this is a no-win situation for him, and he will get blamed for the "Biden" debacle anyway. But we will wait and see.