The outbreak of World War One delivered an astonishing blow to the collective psyche of political and military leadership in Europe, as the carnage of the war’s opening months shattered illusions about industrial war and lifted the proverbial veil from their eyes. It was not merely the collapse of the “short war” illusion which so famously pervaded, but also the unprecedented and unexpected casualty levels, which rapidly surpassed anything that the armies of the old continent had ever experienced.

This was particularly the case because, notwithstanding the infamous carnage of the war’s later great sieges - Verdun, the Somme, and so forth - the war’s opening months were among its very bloodiest. This was because it was in the opening months that the war was still fought in a somewhat mobile and attacking manner, with forces fighting largely in the open. The French, for example, lost just over 300,000 men killed in action in 1914 (despite the war beginning in August), at a loss rate of some 2,200 killed per day. It was only the following year, once the armies had properly dug themselves in, that loss rates stabilized, and in 1915 French casualties were “only” 1,200 killed on a daily basis. These loss patterns reveal, among other things, that the role of trench warfare is frequently misunderstood. Trenches and fortified belts did not lead to the failure of attacking operations; rather, they were dug in response to the astonishingly high casualties suffered in the war’s mobile phase in 1914. Trenches and positional warfare were a reaction to an unprecedented butcher’s bill, rather than its cause.

In any case, the shattering of prewar illusions about both the length of the war and its human costs led to all manner of improvisation and groping problem solving. This occurred at many levels of war making, with belligerent parties seeking ways to lever new allies into the war, open new fronts, and find innovative tactical solutions. In the technological realm, military leadership looked for ways to leverage emerging technologies to gain an edge on the battlefield. This was particularly the case for the Germans, who were strongly incentivized to find an edge wherever they could. The vastly superior human reserves of the Entente - which included not just Europe’s most populous state in the Russian Empire, but also powers in France and Britain that could mobilize vast reservoirs of manpower in their colonies - meant that Germany was always at a stark disadvantage in an attrition game predicated on trading human lives, and it was always Berlin therefore that felt the stronger pressure to change the game.

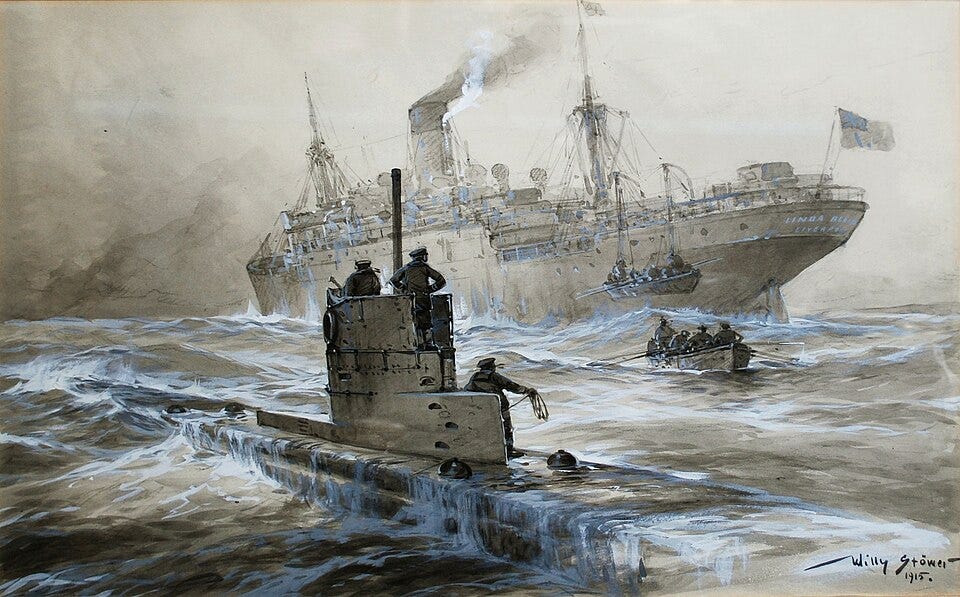

Thus, in the spring of 1915, the world saw three watershed moments on the battlefield in the span of only six weeks, all of them initiated by the Germans. On April 22, French and Canadian soldiers at Ypres became the first men on the western front to endure a battlefield gas attack after the Germans lit upwind canisters of chlorine gas. A few weeks later, on May 7, 1,198 passengers of the Lusitania perished when the ship was torpedoed off the southern coast of Ireland by the German submarine U-20. To cap off the tactical-technological experiments, on May 31 the city of London endured the prototype of what we might recognizably call strategic bombing, when the German zeppelin LZ-38 dropped 3,000 pounds of bombs on the city, killing seven people.

One of the sick ironies of those wretched weeks is the fact that of the three new technological-tactical methods, the gas attack at Ypres was by far the most deadly and terrifying and yet in time it would prove to be by far the most useless. Poison gas produced a powerful psychological effect which was outsized relative to its tactical use, simply because poisoning was such a cruel and spectacular way to die. Men were rightfully afraid of gas, which produced contorted, gasping, agonizing deaths, but countermeasures were quickly developed, particularly against inhaled agents like chlorine and phosgene (mustard gas, which could harm simply from contact with the skin, was somewhat more difficult to cope with). British casualty records indicate that among gas casualties, only 5% were killed or permanently invalid, while a full 70% were fit to return to service within six weeks. The result was a weapon that had a jarring disconnect between its tactical expediency and the horror and moral outrage which it inspired; consequentially, gas never had a real future in warfare and was used on only a handful of isolated occasions in World War Two.

Compared to the gas cloud at Ypres, Germany’s other two technical breakthroughs of 1915 - submarine attack and strategic bombing from the air - had little immediate tactical effect and killed relatively few people in their debuts. The first gas attack at Ypres killed 5,000 allied troops (being the first gas attack against defenseless men, it was the most devastating gas attack of the war) and wounded 15,000. In contrast, the attack on the Lusitania and the aerial bombing of London killed just over 1,200 civilians combined. As we well know, however, the submarine and the strategic bomber - unlike the gas cannister - were emerging weapons that would have major roles to play in future conflicts. More to the point, however, the actions of U-20 and LZ-38 that fateful spring brought a new dimension of terror and range to war, in that both the submarine and the zeppelin killed exclusively civilians.

With their novel and ethically dubious experiments of 1915, the Germans had opened the vertical axis of war. Fighting forces on land and sea had been maneuvering and fighting in two dimensional space from time immemorial, but now aerial bombing dealt death from above, while submarines hunted below the waves. Humanity was now a three-dimensional killing machine.

Age of Immaturity

The submarine is a technological development which is so self-evidently revolutionary that it can be easy to gloss over what it is, precisely, that makes it such a potentially powerful weapons system. In the early 20th Century, it was obvious that the emergence of a viable submarine arm had tremendously complicated the tactical situation at sea, but the great navies of the world still predicated their combat power on capital ships delivering long range gunfire, and submarine fleets were generally undersized, technologically fussy, and tactically immature. To begin, then, we should establish what, precisely, a submarine is. Obviously, a submarine is a watercraft which is capable of operating independently underwater, but in the military sense this is not particularly interesting. It is more important to ask why the ability to submerge a boat (submarines, as a linguistic quirk, are always called boats rather than ships no matter how large they are) might be advantageous.

From the perspective of a fighting navy, a submarine is a vessel which, in comparison to a surface ship, offers a colossal tradeoff between concealment and survivability. That is to say, submarines offer the unique potential to launch essentially undetected attacks, at the expense of extreme fragility. The vulnerability of submarines, which are highly susceptible not only to any direct impact on the hull, but also shockwaves or powerful water pressure, is an important factor in their operational applications and their tactics. As if to underscore the point, the first submarine in history to sink an enemy vessel, the experimental Confederate boat Hunley, was destroyed by her own munitions: by igniting a powder keg at the end of a boom arm, the Hunley did successfully sink a US Navy sloop, but the shockwave caused by the blast killed the entire crew instantly.

What submarines lack in survivability, however, they more than make up for in concealment. This was particularly the case at the outset of the First World War, when there was neither a reliable means of detecting submarines while underwater nor destroying them once they had submerged. Primitive hydrophones offered a modicum of underwater reconnaissance, but most submarine detection occurred via visual detection of either the boat or its periscope - or worse still, by tracking the wake of the submarine’s torpedo once it had been fired.

The essentially undetectable profile of submarines, especially when submerged, was of great importance when the World War broke out due to the extant relationship between naval gunnery and torpedoes. The self propelled torpedo was, very obviously, a novel and extremely deadly weapons system which initially promised to overturn the conventional calculus of combat power at sea. The prospect of sinking expensive, heavily armed battleships with relatively cheap, light, and fast torpedo boats was a tantalizing prospect that had enormous cachet, particularly with the French, who saw torpedo craft as an opportunity to even the odds with the Royal Navy at relatively miniscule costs.

The early promise of fast torpedo boats as dirt cheap battleship killers was scuttled, however, by counterbalancing developments driven primarily by the British. Specifically, three major innovations around the turn of the century substantially dampened the prospects for surface torpedo boats attacking capital ships. In 1887, Armstrong & Company developed a new quick-firing gun capable of firing 12 times per minute, targeting torpedo boats beyond the range of existing torpedoes. This gave battleships an organic fires capability capable of targeting the small and speedy torpedo boats before they could attack. Secondly, a new class of ship - dubbed the Torpedo Boat Destroyer, later shortened simply to Destroyer - was developed to screen the mass of the battlefleet, intercepting and destroying torpedo boats before they came into range. Finally, the transition to the all-big-gun Dreadnought battleships, with their exorbitant firing ranges in excess of 10,000 yards, gave capital ships the prospects of fighting at extreme distances far beyond torpedo ranges.

In short, battleship fleets had developed layered protection which seemed to offer adequate protection from the torpedo boat threats. Battleships would fight from extreme ranges, which would compel attacking torpedo boats to come to them, at which point they could be neutralized by the destroyer screen. If any torpedo craft made it through the screen, they could be engaged by the quick firing guns of the battleships. There was still a torpedo threat to ships that loitered too close to the enemy’s coast, where it might be possible for torpedo boats to quickly dart out, discharge their tubes, and then dash back to safety. The dual threat posed by minefields and by short range torpedo craft operating in the littoral formed an important motivation for the British to adopt a long-range blockade, with the Grand Fleet moored in the safety of Scapa Flow, but on the whole there did not appear to be an existential torpedo threat to a fleet operating far from the enemy’s bases.

Submarines were a novel, potentially game breaking weapons system because they had the potential to neutralize this layered system of torpedo defense by surfacing and attacking undetected at what amounted to point blank ranges. Prewar planning presumed that it would, perhaps, be possible to keep submarines from penetrating into the heart of the battlefleet using the destroyer screen, but this assumption was predicated on visually spotting the enemy’s periscopes. Needless to say, basing the security of monumentally expensive capital ships (with their thousands of crew) on successfully spotting a thin metal tube poking out of the water was a shaky proposition.

The “problem” of the submarine was ably summarized by one of the first attempts to experiment with them in organized maneuvers. First Sea Lord Jacky Fisher was an early champion of submarines, but he envisioned them primarily as coastal defense assets (a theory based on the limited range of early submarines, which forced them to keep near to their bases). In early 1904, therefore, the Royal Navy conducted fleet maneuvers intended to simulate the use of submarines to intercept and attack an enemy fleet approaching the British coast. The exercise pitted Britain’s relatively meager force of just six class-A boats against the battleships of the Grand Fleet, but the submarines - commanded by Captain Reginald Bacon - proved so stealthy and tactically lithe that they were able to score repeated hits with dummy torpedoes. At the conclusion of the maneuvers, the umpires were forced to scratch off two battleships as “sunk.” However, the exercise also served as a reminder of the boats’ fragility: the submarine A-1 was sunk when a merchant ship, which had wandered into the exercise area, drove right over the top of her while she was shallowly submerged.

Notwithstanding the impressive results of the 1904 exercises, the overall promise and role of the submarine remained subject to debate. Admiral Fisher was an enthusiastic proponent, declaring “I don’t think it is even faintly realized - the immense impending revolution which the submarine will effect as offensive weapons of war.” He was fixated on the novel and self-evidently powerful capability to destroy asymmetrically expensive ships via an essentially undetected attack: “Death near - momentarily - sudden - awful - invisible - unavoidable! Nothing conceivably could be more demoralizing.”

Of course, Fisher’s enthusiasm, however effusive and grandiloquent it may have been, was not equivalent to a naval construction policy. Indeed, Fisher’s endorsement of submarines ought to be taken with a grain or two of salt, because it was only a year after the 1904 exercises that his masterpiece, the monster battleship Dreadnought was laid down, at which point the construction of big gun battleships became the guiding animus of the British fleet. Other admirals, however, did not even share Fisher’s theoretical interest in submarines. Admiral Lord Charles Beresford derided them as “playthings” - interesting experiments with no practical application - while Admiral Sir Arthur Wilson went even further and decried submarines as cowardly weapons which besmirched the honor of the Royal Navy by stooping to an “underhanded method of attack.” He concluded his remarks by arguing that the service ought to “treat all submarines as pirates in wartime… and hang all the crews.” Remembering this remark, British submariners would later take to flying the jolly roger while returning to base after successful missions.

Such traditionalist objections to the submarine as an ungentlemanly weapon - “the weapon of cowards who refused to fight like men on the surface” as one officer put it - come across as bizarrely charming to the extent that they are remarkably ungrounded in reality. As we well know now, service on a submarine was not a task for cowards or for the mentally weak, as it entailed grueling work in cramped and uncomfortable quarters on a fundamentally fragile vessel from which there was no escape in the event of being hit. Seamen crewing a surface vessel might have a reasonable chance of abandoning ship, but in the confines of a submerged submarine casualties were invariably total. Submariners have traditionally had strong idiosyncrasies and a unique service culture that sets them apart from the rest of the navy, but they are unequivocally not cowards.

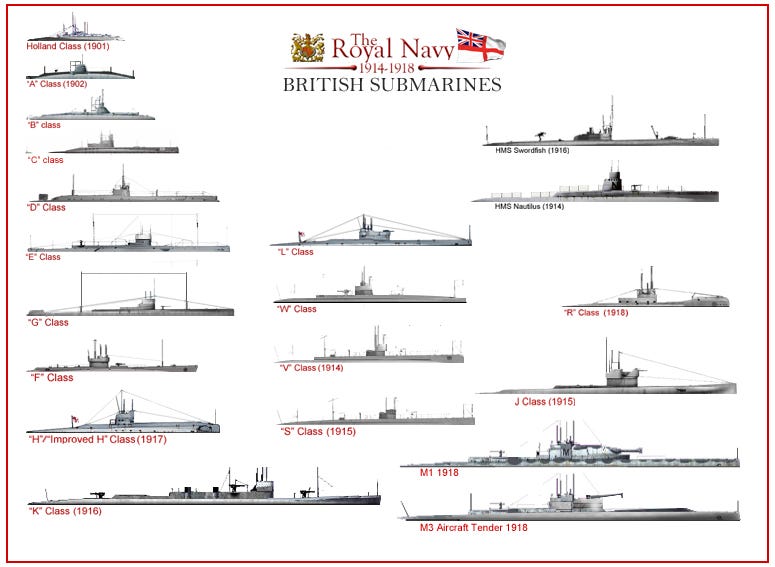

Nevertheless, the submarine arm did have real problems in the prewar period, chief of which was the simple fact that it was an immature technological system. Early British submarine classes - the logically named A’s, B’s, and C’s - were fundamentally coastal vessels with low seagoing endurance and underwater cruising speeds of just 8 knots. It was not until 1907 that the British unveiled the D class, which boasted diesel engines and an impressive 500 ton displacement which made it truly oceangoing, and by extension capable of proactive operations away from the British coast. The 1912 E class was even better, with a displacement of 660 tons, a punchy surface speed of 15 knots (10 knots submerged), and an operating range of some 3500 miles.

Rattling off the ranges and speeds of the various submarine classes is perhaps mildly interesting, but it raises the relevant point, which is that submarines displayed a promising trend, growing larger, more seaworthy, faster, and with much longer ranges. All of this was absolutely necessary for them to become meaningful weapons systems capability of operating at range. However, as the submarine grew larger it also became much more expensive, at a time when navies - particularly the British and German services - were clawing for funds to construct expensive battle fleets of Dreadnought equivalent ships. Many British officers raised the point that the newer models, like the D Class, cost as much as a destroyer while still offering much lower speeds and ranges.

It was difficult to justify massive investment in a weapons system that was still maturing, particularly because the specific tactical application of submarines had yet to be resolved. It was undeniable that torpedoes offered massive destructive potential, but getting submarines into position to attack was much more difficult than it sounds. This is largely due to their relatively slow speed, particularly when submerged. Given their poor underwater speeds, submarines had to move into position ahead of their moving targets. The submarine “attack area” thus necessarily lay in the path of the oncoming enemy, which in turn helped the enemy’s screening destroyers know where, exactly, they needed to screen. The difficulty that submarines had in both locating targets and moving in position to attack is one reason why both the British and the Germans pondered the idea of “submarine traps”, which implied laying a net of submarines in waiting and leading the enemy fleet into them. If submarines had difficulty catching up with the enemy, it was just as well to lead the enemy to them. Other suggestions included the use of submarines to enforce a close blockade of enemy ports, as a submerged submarine was the only type of vessel that could loiter safely near the enemy coast for any extended period of time. For this, of course, they would need ever greater range and endurance.

The crux of the issue, in other words, was that submarines offered a very powerful capability which had not yet been converted to a definitive tactical methodology. In other words, this was a novel weapons system which was the subject of imagination and experimentation, and cash strapped navies - already trying to scrape together every possible pound or mark to build battleships - were disinclined to spend heavily on imagination, and in any case the shipyards could not easily scale up to produce subs at scale.

Given the muddled tactical schema, it was perhaps natural that the Submarine services fielded a wide variety of models with limited production runs. For the British, the true workhorse was the E class, of which eleven were in service with the Royal Navy at the outbreak of war. The beginning of actual hostilities has a way of clarifying priorities, and in the case of the Royal Navy it induced a decision to simply serialize production of their most successful model, which was the E. Consequentially, a total of 58 E boats would be built by the end of the war.

However, the British continued to muck about with experimental designs, including the so-called “Oceangoing” Submarine, which was intended to have the requisite surface speeds to sail with the Grand Fleet. These models, which included the experimental Swordfish and Nautilus, eventually spiraled into the misbegotten wartime K class. The K’s were true monstrosities; driven by Admiral Jellicoe’s demands for a submarine that could keep pace with the surface fleet, the Ks metastasized into behemoths far larger than any extant submarines, capable of making some 24 knots and operating with the fleet. The cost of this speed, however, was a sprawling hull with poor dive handling, and above all - the true insanity - a steam powerplant in place of the diesel which had become ubiquitous on submarines.

The problem with steam on a submarine is simple: a steam powerplant generates enormous heat and furthermore requires a complex of funnels, exhausts, and air intakes, all of which have to be closed up in order for the submarine to dive. In order to actually submerge the boat, the crews had to extinguish the boiler fires and conduct a lengthy procedure to close up all the various ports and exhausts feeding the powerplant. The Ks therefore took half an hour to prepare for a dive, making it impossible for them to rapidly submerge upon sighting the enemy. Furthermore, the boat was always at risk of sinking if even one of these ports was not properly sealed. This was the fate of K13, which sank in 1917 with total loss of life after an air intake failed to seal properly and flooded the engine room. To make matters even worse, the Ks were so long, and tended to dive so steeply, that it was possible for the bow of the boat to be at the maximum dive depth while the stern was still practically at the surface. In short, this was a submarine that could not really submerge very well, which would seem to be an important capability for such a vessel. One officer complained that, for a submarine, the Ks simply had “too many holes”, while Ernest Leir, the Captain of K3, joked that “the only good thing about K boats is that they never engaged the enemy.” After six of the eighteen Ks were lost to accidents, the series was rather appropriately nicknamed the “Kalamity class.”

Taken together, the state of the British submarine force was somewhat confused, but not necessarily confusing. Early construction schedules consisted largely of the relatively cheap but limited early classes (A-C), which were useful mainly for coastal defense roles. The strongest proponents of submarines at this time included Admiral Fisher and Winston Churchill, who received routine recommendations to “build more submarines” from Fisher after the latter’s retirement in 1910. By 1912-14, the British had landed on a truly suitable workhorse design in the E class, but misguided demands from the admirals - for example, Jellicoe’s ask for a submarine capable of cruising with the fleet - led to a variety of unproductive side projects, like the steam powered Ks, which would prove essentially useless as military assets.

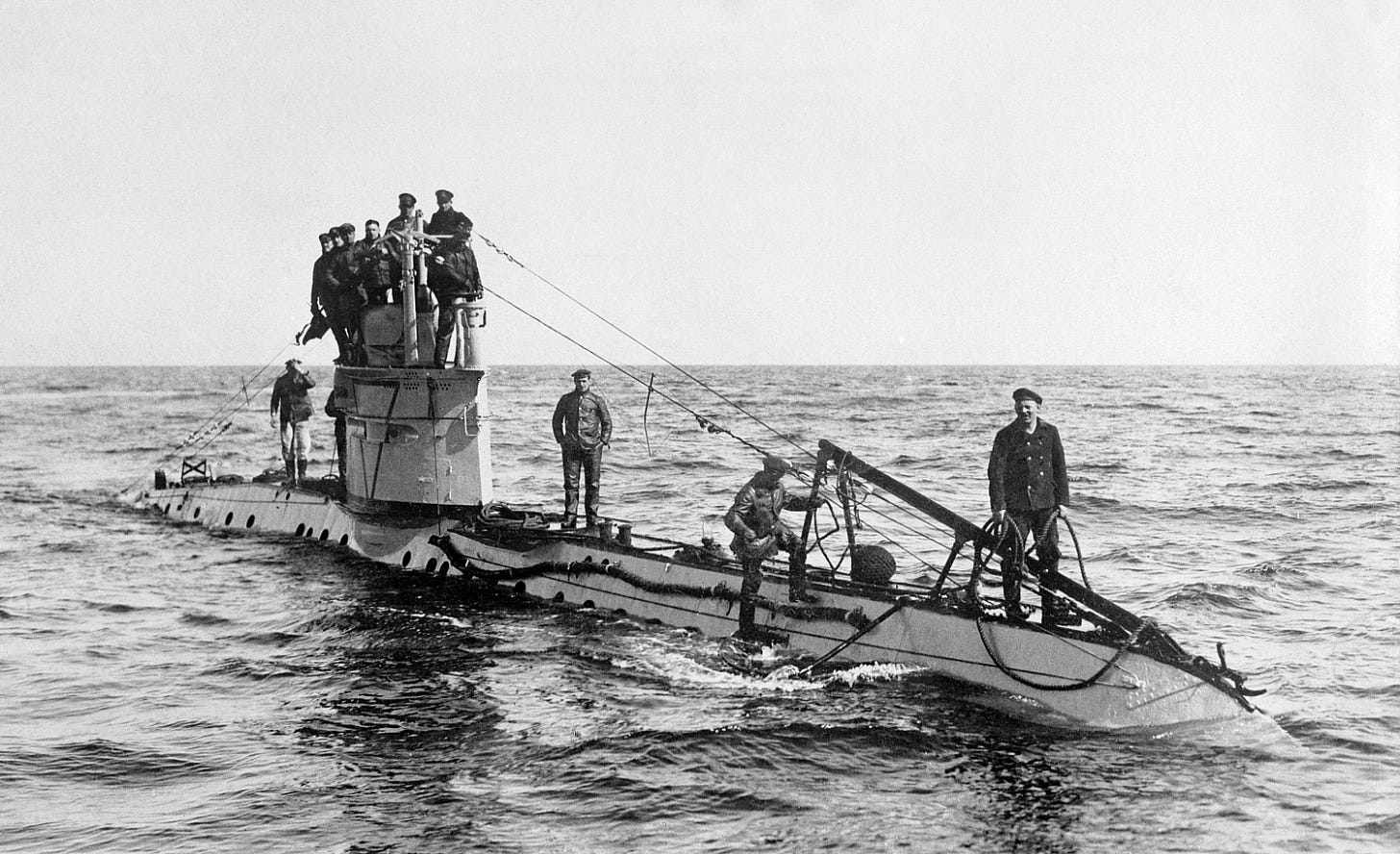

On the far side of the North Sea, the German attitude towards submarines was much different, and ensured that the Imperial Navy’s submarine fleet was far too small for the tasks that would be thrust upon it during the war. The architect of Germany’s fleet, Admiral Tirpitz, famously had little interest in submarines, quipping that he could not afford to finance “experiments.” This comment is frequently interpreted to cast Tirpitz as an unimaginative man with a hyper fixation on battleships, but there was a coherent framework to his thinking. Tirpitz was manifestly interested in building a “visible” fleet to build deterrence, and submarines did not contribute to this objective. Tirpitz was also focused on building a blue-water fleet capable of fighting on the high seas, which naturally dampened interest in early submarines, with their short ranges confining them to coastal defense roles. So, while the Royal Navy had a modicum of interest in early short-range submarines (As, Bs, and Cs) for littoral operations, Tirpitz did not. It was not until improvements in diesel engines gave submarines longer legs that they became systems of interest for Germany. The upshot of all this is that while the famous U-boats (for the self-explanatory Unterseeboot) are thought of as an iconic German weapons system, Germany had far too few of them when the war began.

German submarine construction was also hampered by the structure of German naval building, which was predicated on “naval laws” passed by the Reichstag which enshrined naval construction timetables over the course of many years. Germany’s 1912 naval law called for a fleet of 70 U-boats to be completed in 1919, and an expanded program proposed in 1915 looked for a completion date of 1924. Obviously, given the timetables of World War One, this was not a particularly realistic or useful timeframe, but it reflected both the improperly low priority initially given to the U-boat force and flawed assumptions about how long the war in Europe would last. The expanded U-boat fleet proposed in 1915, for example, was designed on the assumption that the war would end soon and submarines would be needed for some unscheduled later war with England.

First World War U-boats were generally adequate vessels largely equivalent to British E class submarines, with strategic ranges in the thousands of kilometers. German boats accrued significant advantages from their efficient diesel engines, particularly a 4-stroke supplied by MAN (Maschinenfabrik Augsburg-Nürnberg). Sufficient range was particularly important for the Germans if they wished to operate beyond the North Sea and seriously interfere with naval traffic to Britain. Given the efficiency of their diesels, however, the Germans were able to operate U-boats in the Irish Sea, the north Atlantic, and the Mediterranean. The issue was that, given Germany’s inability to conduct a crash building program, there were simply never enough U-boats to go around.

On April 1, 1915, when the German naval command first began exploring the possibility of using U-boats to implement a blockade of the United Kingdom, there were only 27 oceangoing boats on hand. Counting ships ordered and under construction (and accounting for expected losses) the Germans could count adding 13 additional boats by the summer of 1916. At the same time, however, naval planning estimates indicated that a full blockade of Great Britain would require at least 48 U-boats, plus an additional 56 for other fleet operations and replenish expected losses. This put the overall ledger at 104 boats needed against just 40 available.

The estimated requirement of 104 U-boats, however, turned out to be a somewhat deliberate underestimate designed to provoke accelerated construction. In February 1916, the German Admiralstab prepared a much more comprehensive plan for unrestricted submarine warfare against the British, which called for a far larger fleet. This plan called for no less than 27 U-boat operating areas (analogous to hunting grounds) occupied by 170 oceangoing boats. To this were added boats required for patrolling the Heligoland Bight (tasked with keeping it clear of British boats to allow the U-boats to get in and out of their bases), a reserve, minelaying U-boats tasked with mining against both Britain and Russia, and a force of boats that could operate with the fleet. When everything was added up, the navy’s 1916 plan called for an eyepopping 366 torpedo U-boats and 117 minelayers. Reading this proposal must have been disorienting. In fact, Germany by this point could count a grand total of 119 torpedo U-boats and 14 minelayers.

The exorbitant estimates of 1916 were obviously so far beyond Germany’s potential force generation that, in real time, they served almost no real purpose. For us, however, they are interesting because they indicate what the German admirals thought they needed to successfully prosecute a war-winning submarine campaign. Despite having a force that was far short of their estimated requirements, they ended up attempting an unrestricted submarine campaign anyway. The First World War upset most of Europe’s assumptions about how future conflicts would be fought, but in light of the German Admiralstab’s 1916 proposals, submarines surely stand out as one of the key misses. After being treated as an essentially ancillary system during the prewar naval buildup, particularly by the Germans, who were guided by Tirpitz’s emphasis on a visible fleet of blue water capital ships, by 1916 they had come to be a critical arm on which Germany’s hopes increasingly rested.

The Multivariate Problem

By far the most famous use of submarines, at least in their pre-nuclear iterations, was as platforms for sinking commercial vessels. The imagine of U-boats prowling the Atlantic, preying on helpless merchant shipping, came to utterly overshadow the other, more theoretical tactical applications, which included coastal defense, minelaying, submarine traps in concert with fleet operations, screening lines, and so forth. However, at the outset of the Great War it was not at all obvious that attacking merchant shipping was a proper role for submarines, and the concept faced serious obstacles which required a revolutionary radicalization of war at sea.

At the turn of the century, naval warfare was governed by various conventions and treaties which apparently made submarines utterly unsuitable for operations against merchant shipping. Chief among these were the so-called Prize Rules, which governed the “taking” of civilian vessels under wartime conditions. These regulations originated in attempts by the European powers to delineate between lawful blockade and piracy, particularly as the world moved to abolish the ancient practice of privateering (the granting of a license allowing private warships to lawfully board and raid the enemy’s shipping). Extant rules governing blockades stipulated that there were various grades of contraband that were lawfully subject to seizure, but even more importantly they dictated that blockading vessels were obligated to stop the target merchantmen and conduct an orderly inventory (to ascertain if the cargo was indeed contraband) while guaranteeing the safety of the civilian crew and passengers.

The rules of interdiction dictated by the prize rules underpinned theories of long-range cruiser warfare, which supposed that speedy armored cruisers could range into sea lanes to intercept and capture the enemy’s shipping. This had obvious appeal in any war against Great Britain, which by the 20th Century had become heavily dependent on imports of vital industrial inputs and raw materials. Germany, however, had eschewed a cruiser-based raiding strategy on the grounds that it lacked the overseas bases and coaling stations required to sustain these vessels, particularly if they were cut off from German home ports by the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet.

Submarines, it would seem, offered a substitute for cruisier warfare, particularly as the new diesel models with their extended ranges came online. Unlike a cruiser, a U-boat had good odds of slipping out of the North Sea, and their powers of concealment made them much harder to run down. The problem, however - leaving aside the fact that Germany had just 28 U-boats when the war began - was that submarines were extremely fragile, which made it very dangerous for them to follow the prize rules. This was particularly the case once the British began adding concealed guns to merchant ships, creating the so-called “Q-ships”. A surfaced, immobile submarine was a very vulnerable target indeed, even against the modest guns carried by the Q-ships. It does not take much imagination to picture a German submarine surfacing, flagging down what is believed to be a defenseless merchantman, and then taking shots at point blank range as she pulled alongside to board.

The Q-ships proved more than capable of sinking U-boats attempting to implement the prize rule. In June, 1915, the Inverlyon sank the submarine UB-4 with the loss of all hands in the North Sea, after raking her with shots from a single 3-pound gun. A few months later, the HMS Baralong sank U-27, in an incident that became somewhat infamous after the Baralong’s captain ordered the surviving German sailors to be shot in the water. Incidents like this demonstrated how dangerous it was for U-boats to operate under the prize rules, and deeply embittered German attitudes towards British merchantmen - particularly because the Q-ships concealed their armament to look like ordinary cargo ships, which was taken as essentially equivalent to perfidy. The upshot of all this was that, for the U-boats, it was tactically senseless to surrender their greatest advantage - concealment - by openly surfacing and attempting to board and search the enemy. The solution, obviously, was to simply treat enemy shipping like military targets and sink it, unannounced, with a concealed torpedo attack.

Tactically speaking, therefore, submarines could only be a substitute for cruiser warfare if they did away with the prize rules altogether and sank shipping outright as a matter of course. This was manifestly a violation of international law, and a tactic which ultimately hinged on an element of terror and randomness. The decision to wage “unrestricted submarine warfare”, which functionally meant the unannounced sinking of all naval traffic entering the declared “war zone” around Great Britain, was therefore not merely a tactical question, but a rather nebulous strategic problem which had to take into account the danger of angering neutrals, and in particular the United States. These calculations took place parallel to a more concrete tactical math problem, related to the actual quantity of shipping that could be sunk by the limited German U-boat force.

In other words, unrestricted submarine warfare presented a nested set of difficult calculations. On the purely tactical level, the issue was that submarines were not exactly a direct substitute for an effective naval blockade. Submarines could not seize contraband cargoes, they could not capture ships and install prize crews, and they could not maintain a permanent and visible present off the enemy’s coast. What they could do was sink ships, and the relevant question was whether they could sink enough enemy shipping to *simulate* the effects of a blockade. This was always a shaky proposition, given the relative scarcity of U-boats, the fact that only a small portion of the force could actually be on patrol at any given time (the remainder being either in port or transiting between their bases and their patrol areas), and the surprising difficulty that submarines had in locating targets on the open seas. These tactical calculations occurred within the context of a larger risk-reward calculus which weighed the diplomatic costs of attacking neutral shipping against the potential economic damage imposed on the British. These were all questions without clear answers, to the effect that unrestricted submarine warfare became a method that the Germans would dial up and down as their sense of strategic frustration and the strength of the U-boat force fluctuated.

When the war began, the cost-benefit analysis on unrestricted submarine warfare was not particularly strong. One of the idiosyncrasies which shaped early war operations were the vastly different assumptions animating the British and German fleets. Admiral Jellicoe of the Royal Navy presumed that mines and torpedo craft would make it cost prohibitive for capital ships to operate openly in the North Sea, and he based the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow, far to the north of Germany’s bases. The Germans, on the other hand, were fully anticipating an attempt by the British to engineer a decisive fleet battle at the outset. Given the limits of the U-boat force, the German preoccupation was therefore how to use submarines in the anticipated general fleet action.

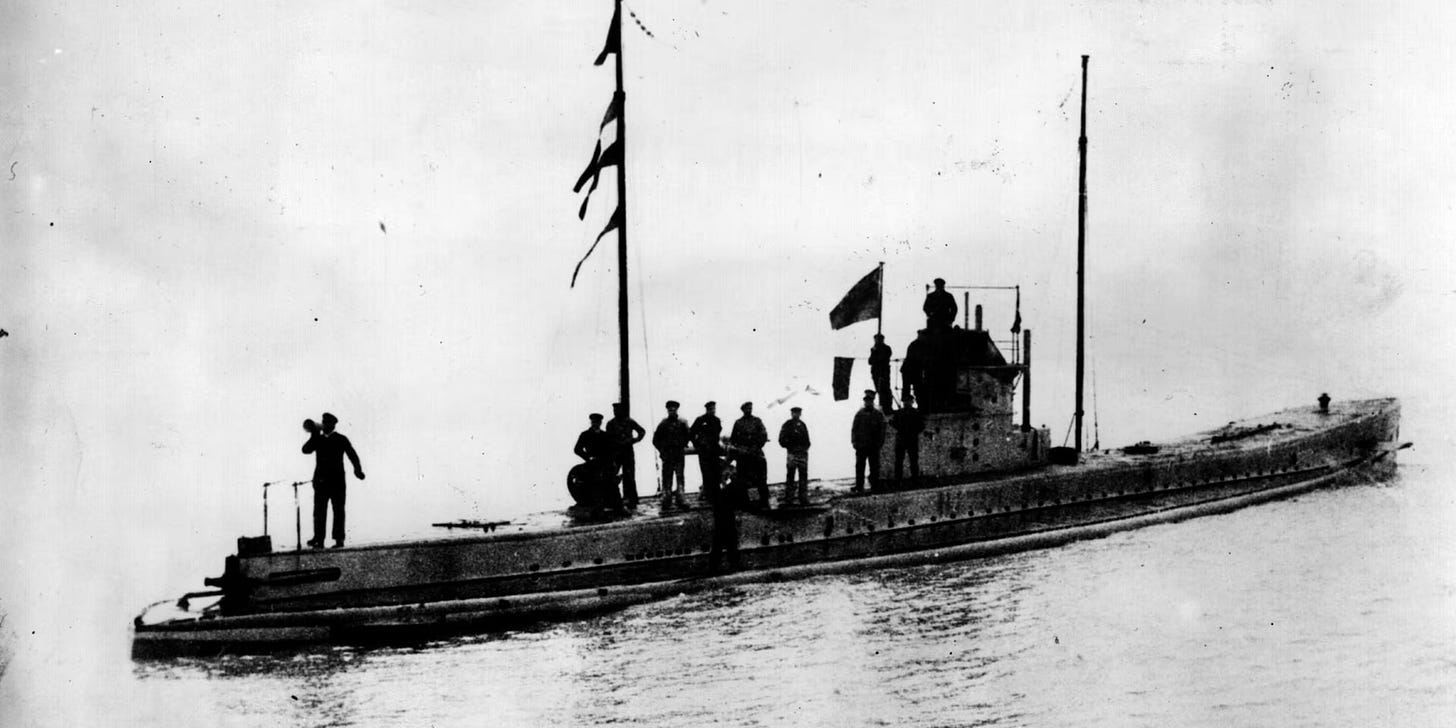

The initial German deployment scheme utilized a screening line of destroyers stationed some 30 miles out at the edge of the Heligoland Bight, with a secondary line of submarines 10 miles inside this outer screening line. These U-boats were spaced at roughly equidistant intervals, tied up to mooring buoys on the surface. The notion, apparently, was that as the British Grand Fleet approached, the outer line of destroyers would immediately withdraw back into the bight; the retreat of the screening line would be the signal for the U-boats to cut loose of the buoys and submerge, in preparation to launch torpedo attacks on the oncoming British ships. On paper, it was hoped that the U-boat screen would be able to score a modicum of hits and even the odds before the fleets engaged in the Bight. In other words, U-boats were viewed as a supplementary component of the Bight defense, rather than an independent arm for waging proactive operations.

The first proactive use of the U-boats was as a reconnaissance force. Commander Hermann Bauer, who commanded the submarine force, organized a flotilla of ten U-boats which were tasked with sweeping the North Sea to locate the Grand Fleet and, if possible, identify the disposition of British blockading lines. They ran northward across the sea on a 60 mile front, attempting to probe all the way to the Orkneys north of Scotland. Beginning on August 6, 1914, nine U-boats (one had encountered engine trouble shortly after departing and had to turn back) made a 350 mile sweep across the North Sea. Remarkably, despite ostensible searching an area of some 21,000 square miles, the seven submarines that returned to base on August 12 reported that they had not encountered a single British warship. As for the two missing U-boats, U-15 had encountered the light cruiser Birmingham in the Orkneys and been sunk by the British ship, and U-13 had apparently simply vanished. Unfortunately for the Germans, U-15 actually had something interesting to say: she had reached the Orkneys and ascertained that the British Fleet was loitering there, safely out of reach of the German Navy. Obviously, however, her ill-fated encounter with the Birmingham prevented her from relaying this insight to the Naval Staff.

The reconnaissance mission of August did little to instill confidence in the U-boats. Ten boats had conducted a relatively wide-ranging sweep of the North Sea and returned without damaging, let alone sinking, a single British ship, while losing two submarines. Not only that, but they had returned with no actionable intelligence of any kind, other than confirming that the British were not implementing a close-range blockade. Prewar expectations for the submarine force were not high, and this experience did little to raise them. As one German officer put it, “Our submarine fleet was as good as any in the world, but not very good.” Given the denigration that the Germans initially laid on their own U-boat force, it is truly remarkable that the submarines soon became a critical arm on which Germany laid much of its hopes for victory.

The paradox of the naval war was the plain fact that, notwithstanding the enormous resources that had been poured into the German and British fleets, the North Sea was relatively devoid of ships. Jellicoe was adamant that torpedoes had turned the North Sea into a dead zone, and the German High Seas fleet - expressly built to contest at the edge of the Bight - lacked the range to strike out in a meaningful way. Not everyone shared Jellicoe’s caution, however, and several British ancillary forces continued to operate in the Channel and the southern end of the North Sea with relatively lax protection against submarines. One such force was a squadron of Bacchante class armored cruisers - worn out and weary ships built in 1889, hastily mobilized out of the Reserve Fleet at the outbreak of war and tasked with screening the entrance of the Channel, ostensibly to protect the convoys ferrying the British Expeditionary Force and its supplies to France.

The Bacchantes were slow and old, crewed by men called up from the Fleet Reserves, with their officer ranks filled out by cadets from the Royal Navy College. Plodding along a patrol line off the Dutch Coast, it is difficult to imagine more accommodating targets. Captain Roger Keyes wrote to the Admiralty’s Operations Division: “Think of two or three well-trained German cruisers… For Heaven’s sake, take those Bacchantes away! The Germans must know they are about and if they send out a suitable force, God help them….” What is interesting about Keyes’s warning is that he was worried about the Bacchantes coming under attack by German surface ships. This is unusual because Keyes was himself the head of the British submarine service, yet he apparently did not consider submarines to be the pressing threat. The Bacchantes were not withdrawn from their patrol duties, though officers in the Grand Fleet (which was safely ensconced in the Orkneys) took to calling them the “live bait squadron.”

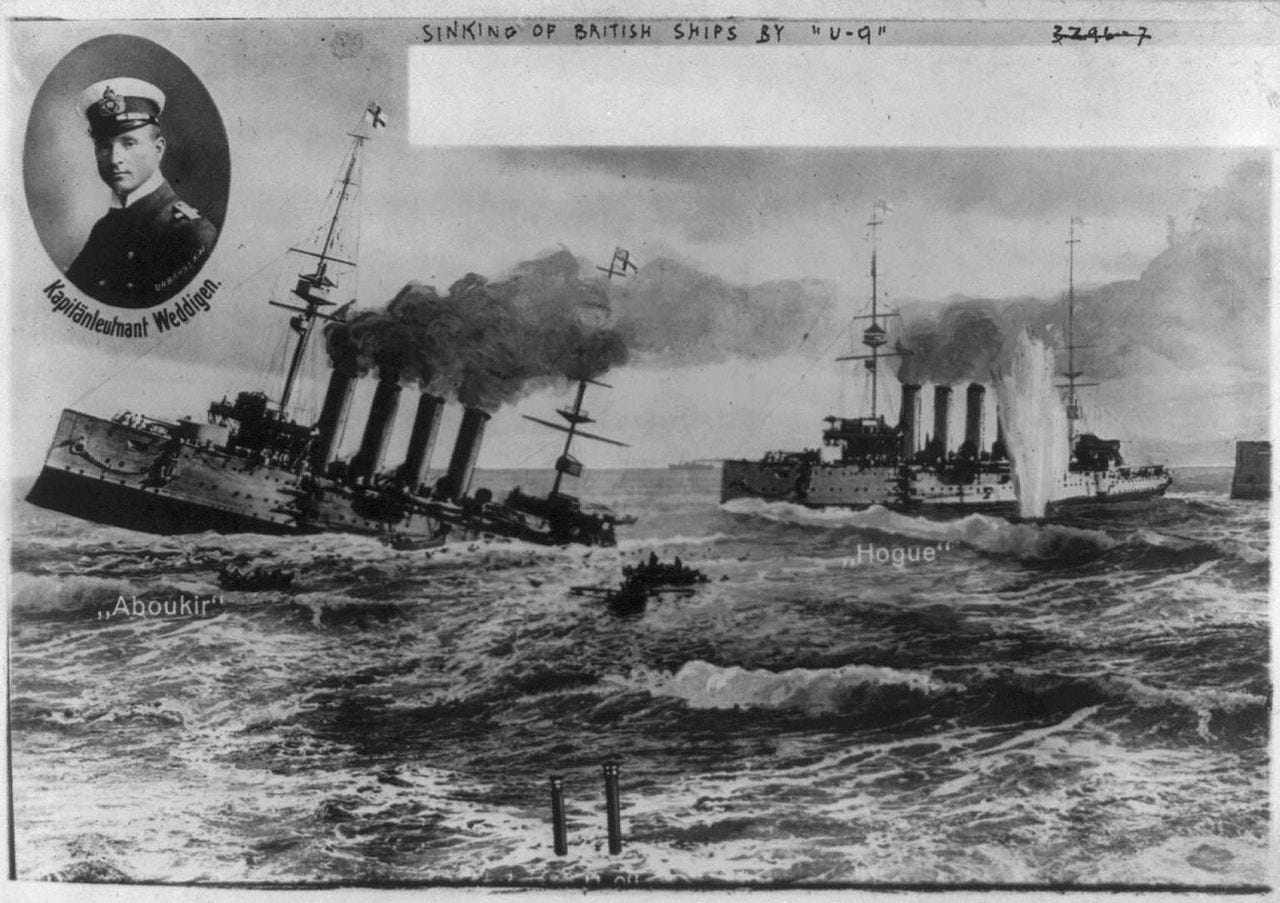

At 6:30 AM on September 22, three of the Bacchantes - the Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy - were steaming along their patrol line when a massive explosion ripped apart the Aboukir’s starboard side. She had been torpedoed by the hitherto undetected German submarine U-9, which had sighted the British cruisers on the horizon at dawn.

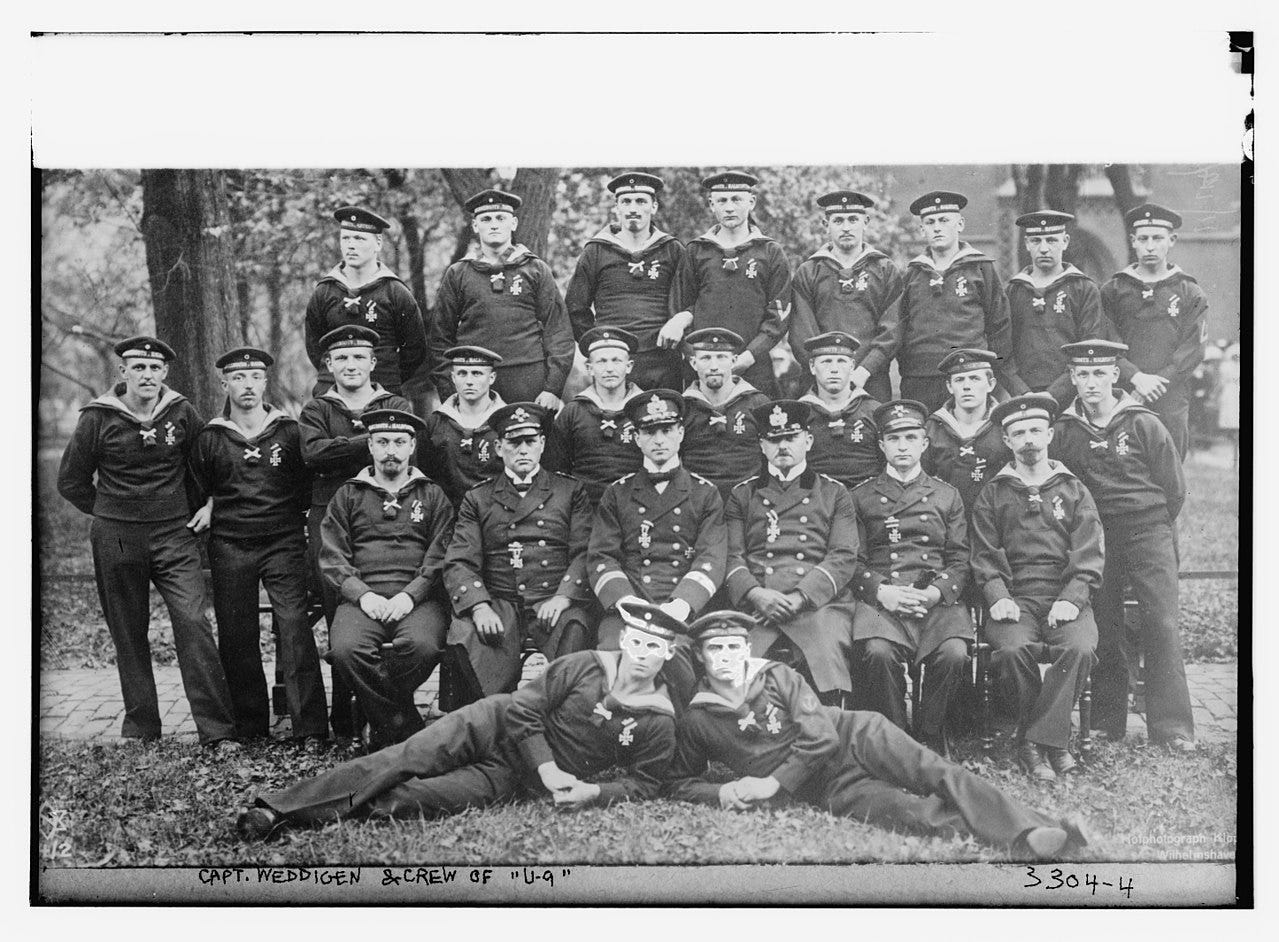

U-9 was captained by one Otto Weddigen, who was something of a legend, at least as far as early submariners went. In 1911 he had survived the sinking of U-3 during a training exercise in Kiel Harbor (somebody left a ventilator open) by using pressurized air to vent the boat’s forward buoyancy tanks, temporarily floating the bow of the vessel to the surface. Weddigen then led his crew of 28 men on a precarious climb up to the bow (the boat was now suspended at a sharp incline with the bow at the surface and the stern in the deep), before they escaped from the sinking boat by crawling through an 18 inch wide torpedo tube. Weddigen therefore understood better than most the risk of being a submariner, but he took his profession with deadly seriousness, and was well known for drilling his handpicked crew relentlessly.

Weddigen was, in other words, a fitting character to score one of the submarine’s first great tactical coups. He was eating his breakfast that morning when the word came down that the Bacchantes had been spotted. He immediately abandoned his meal and ordered a dive to periscope depth. He steered the submarine towards the cruisers, aiming for the middle of the three ships, alternately raising and lowering his periscope to maintain concealment. At 6:20 AM, he came to the surface, fired a single torpedo at the Aboukir and immediately dove. The torpedo hit the cruiser amidships below the water line and immediately flooded the engine rooms, and the Aboukir began to sink rapidly. Within 25 minutes, she capsized completely.

As the Aboukir went belly up, the well-intentioned captain of the Hogue, Wilmot Nicholson, steamed at low speed towards the wreck to take on the many survivors who were by now spilling in the water. He ordered his men to throw tables and chairs overboard for the men in the water to grab on to while he prepared to lower his boats to recover them. Before he could begin the rescue, however, the Hogue was ripped by a pair of blasts from two torpedoes. After hitting the Aboukir, Weddigen had gone back down to periscope depth and reloaded his discharged tube. Although he noted, with some regret, the plight of the “brave sailors” now struggling in the water, he fired both his forward tubes at the Hogue. She too began to sink, and Weddigen and his crew watched with unease as the remaining cruiser - the Cressy - loitered and did her best to recover the mass of flailing men now struggling in the water. Now with just three torpedoes left on board (two in the stern tubes and a reserve for the bow), Weddigen rotated U-9 and fired both stern tubes at the Cressy, scoring one hit. He then came back around and fired his last torpedo off the bow, putting a capper on his shooting spree, before hightailing back to base. The Cressy sank at 7:55 AM.

Weddigen’s exploits on September 22nd spoke for themselves. The Bacchante class were old warships with limited value in fleet operations, but this did not abrogate the spectacle of a single submarine sinking three armored cruisers in the space of barely 90 minutes. Although a few hundred sailors were rescued, first by Dutch civilian boats and then by British destroyers responding to the distress call, the vast majority were killed. A total of 837 men were fished from the water alive, while 62 officers and 1,397 sailors drowned. Jacky Fisher raged that U-9 had killed more of his men than Nelson had lost in all of his battles combined. The scene was shocking, and it made a deep impression on Weddigen, who felt deep admiration for the British sailors, and reported: “They were brave and true to their country’s sea traditions.”

It was revolutionary for a single submarine to achieve something so impressive. Weddigen instantly became a hero in Germany, and both he and his crew were lavishly decorated by the Kaiser. The British at first refused to believe that the attack had been the work of a lone submarine. The Times reported that German submarines always operated in groups of six, and “If it is true that only one, U-9, returned to harbor, we may safely assume that the others are lost.” However, Weddigen’s coup served as a bolt of lightning to the submarine war, inducing the British to roll out new regulations and countermeasures (for example, zig-zagging to confound torpedo ranging and prohibiting large warships from stopping in place to take on survivors from sinking ships) and it produced a new German interest in U-boats as a potentially decisive weapon.

The realization that submarines were serious weapons, and not “experiments” as Tirpitz had famously called them, dovetailed with growing frustration at the British blockade to push the Germans into their first foray with unrestricted submarine warfare. The foundational fact to understand in this regard is the simple reality that Britain’s blockade of Germany was “illegal.” This is a term which is always precarious to introduce in the context of war; at the risk of going down a lengthy and potentially unproductive tangent, there is really no such thing as “laws” of warfare. What matters, ultimately, is winning. A brief perusal of individuals and states brought to account for violating the “laws of warfare” reveals essentially a list of losers. However, within the parameters of international convention at the time, Britain’s blockade was clearly illegal, in that it operated at great distance from the German coast and attempted to interdict all traffic into the North Sea. The declaration of the entire North Sea as a warzone was not something that international treaties proscribed, and neither was the British interdiction of items like food, which were not considered war-related contraband.

The legality of Britain’s blockade did not end up mattering very much, because Britain won the war and successfully managed its diplomacy to avoid alienating neutral powers like the United States. The USA, just as an aside, did complain frequently about Britain’s blockading practices, but as we know America ultimately entered the war as a British ally. Therefore, though the “illegality” of the blockade is essentially indisputable, it ought to be classified as an extremely successful and calculated violation, which is the best kind.

What did matter a great deal, however, is that the British blockade greatly irritated and outraged the Germans, and Britain’s perceived indifference towards the “rules” of blockading encouraged the Germans to retaliate with their own violation of international law by unleashing the U-boats. In December, 1914, Tirpitz gave an interview to an American correspondent in which he complained about America’s failure to intervene against the illicit British blockade, and argued that Germany could retaliate with a U-boat campaign. “We have the resources”, he claimed, “to torpedo every English or allied ship approaching a British port.” This was not exactly true, but it underscored the German belief that unrestricted submarine warfare was an appropriate response to Britain’s blockade.

The first German attempt at a submarine blockade, which began in February 1915, can be thought of as a cathartic reprisal against the British blockade which went terribly wrong. To begin with, it seems fairly obvious that submarine warfare always threatened to be a more inflammatory violation of international law than the blockade, simply because sinking ships unannounced is a far more violent and shocking act than conducting an orderly seizure of their cargoes. Furthermore, the decision to take recourse to submarines completely reversed a growing frustration with the British on the part of the neutrals. Opinions in America were strongly against the British blockade and the “insolent aggressions” which the British displayed when they seized America’s “peaceful trading ships.” The Secretary of the Interior, Franklin Knight Lane, griped: “The English are not behaving very well. They are holding up our ships; they have made new international law… Every day… we seethe a little more at the foolish actions of the English.”

The Germans failed to understand, however, that the most decisive battleground of the war was neither the North Sea, nor the trench lines in France, nor the rolling front in Eastern Europe: rather, it was the war for American sympathy. Mounting frustration with the English blockade, the loss of U-boats attempting to comply with the prize rules, and a growing sense of impotence on the part of the German navy compelled them to roll the dice with what was, apparently, the best weapon that they had. In particular, the decision to attempt unrestricted submarine warfare was goaded by a pair of British policies which the Germans viewed as underhanded treachery: namely, the practice of concealing weaponry on merchant ships (the Q-ships) and a January 1915 order from the British Admiralty that British merchant vessels should fly the flags of neutral countries to evade German submarines. With the British now both disguising armed warships as unarmed merchantmen, and disguising their own vessels as neutral ships, the frustration had reached a boiling point. On February 4, 1915, Admiral Hugo von Pohl published a warning:

The waters around Great Britain and Ireland, including the whole of the English Channel, are hereby declared to be a War Zone. From February 18 onwards every enemy merchant vessel encountered in this zone will be destroyed, nor will it always be possible to avert the danger thereby threatened to the crew and passengers. Neutral vessels also will run a risk in the War Zone, because in view of the hazards of sea warfare and the British authorization of January 31 of the misuse of neutral flags, it may not always be possible to prevent attacks on enemy ships from harming neutral ships.

Similar warnings were published in the United States by the German embassy. The policy was highly cathartic, and was imagined in Germany as a proportionate response to Britain’s own illegal blockading measures and their perfidious use of neutral flags. The campaign suffered from the beginning, however, from twin defects: namely that there were simply not enough U-boats to enforce an effective blockade, and the spectacle of simply sinking civilian vessels unannounced was taken as an act of barbarism. To neutral powers, even those like the United States that strongly opposed the British blockade, unrestricted submarine attacks did not appear to be a proportional response at all.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.