The assault on Normandy On June 6, 1944 is likely the single most dramatized moment in American military history. It has so far been depicted in three famous big budget productions - the amphibious landings in Saving Private Ryan, the airborne drop in Band of Brothers, and the entire package in the 1962 war epic, The Longest Day. With the addition of countless video game adaptations and the deeply entrenched trope of Greatest Generation lore that permeates American culture and politics, it is safe to say that Americans have a stronger impression of the D-Day landings than they do any other event in the American martial tradition.

This makes it rather difficult to discuss the battle for Normandy in an emotionally neutral light. Some people want to center the discussion on the beach because it is familiar, but this stems from a sort of childlike desire to hear our favorite stories told again. There is nothing wrong with this, of course, but it is not particular interesting from an intellectual or historical standpoint. Others, from outside the American perspective, like to hear Normandy debunked or retold - either because they are tired of the Anglo-Canadians being shoved aside or left out of the heroics, or because they are tired of American supremacy and want to diminish past American glories. Perhaps these are understandable impulses, but again they fail to be very interesting.

Normandy ought to instead be thought of as a major departure in the trajectory of the American armed forces. As we previously discussed, early American attempts to go toe to toe with the Wehrmacht went rather poorly, with US forces leaning heavily on superior firepower to salvage botched operational situations. The Kasserine Pass, in particular, was a harrowing experience for rookie American troops, and the famous biopic Patton begins with American forces in Africa languishing in a sorry state, with the titular General being rushed in to whip them into shape.

In Normandy, however, the US Army was transformed into an entirely different sort of animal. Rather than frantically calling in firepower to stabilize tenuous situations, the Americans developed operational techniques that simply crushed the Germans, running through them “like crap through a goose”, as Patton put it. The Wehrmacht always prided itself on its superior prowess in maneuver and its dominance in fluid operations, but in Normandy they were surpassed, humiliated, and destroyed in a campaign which launched the United States into its era of military supremacy and unparalleled swagger.

We can broadly think of America’s operational conduct of the war against Germany as occurring in two distinct phases. The first phase, essentially comprising the campaign in North Africa and the early encounters in Italy, revolved around learning how to contend with the German panzer package - in these initial operations, American forces faced a steep learning curve in combat against a veteran and lethal Wehrmacht, and American commanders in places like the Kasserine Pass or the beaches at Salerno tended to lean heavily on America’s awesome reservoirs of firepower as an answer to more agile and decisive German forces. This first phase could be thought of as a reactive stage, with the Germans doing most of the maneuvering and the Americans using superior firepower and air assets to counter them.

In the second phase, the US Army emerged as a first class combined arms force in its own right, capable of moving like lightening when it wanted to. Having first learned in the Mediterranean theater that they had the assets in the toolbox to paralyze the Wehrmacht and beat off its attacks, the American forces in France would demonstrate a potent capacity of their own to maneuver and to deploy a devastating assault package. In other words, 1942-43 was about learning to defeat the German armored force and suffocate German maneuver, and 1944-45 was about the US Army learning to maneuver in its own way. Armies are, after all, learning and evolving organisms, and the US Army that fought in France was in many ways unrecognizable from the inexperienced force that had washed ashore in Africa.

Before we can look at the specifics of the American operations in France, it may be fruitful to note two idiosyncrasies of the US Army as it relates to operational maneuver - namely, that it was both materially easy and frequently unnecessary.

On the first count, we ought to note that of all the combatants in World War Two, the United States had by far the easiest time with mechanization and motorization, speaking from a technical perspective. America is one of the great oil producing nations of the world - and this was especially true in the 1930’s, when middle eastern production was not yet unleashed. At the outbreak of war, the USA was responsible for over half of the world’s oil production. As a result, American was a highly motorized society, with mass adoption of the private car and commercial trucking, and a correspondingly titanic automobile industry.

The upshot of all this was that uniquely among all the belligerent parties, the United States found it almost trivially easy to motorize its ground forces - churning out trucks, halftracks, recovery vehicles, and jeeps by the tens of thousands. This made the order of battle against the Germans oddly asymmetrical; whereas the Wehrmacht had to carefully count and curate its precious mobile formations - the Panzer, Panzergrenadier, Light, and Motorized Infantry divisions - the US Army never needed these designations simply because the mass of its Infantry Divisions were motorized by default. The US Army, also most unlike the Germans, further benefitted from an enormous truck lift capacity - the idea of using livestock to haul crates of ammunition or drums of fuel up to frontline units was completely alien to Americans. As an organically motorized force, the US Army simply had no need to think deeply about how to allocate mechanized units.

What all of this meant, in a word, was that the US Army could move like lightning when it wanted to. Unlike the Wehrmacht, this was not a military that was conditioned to be constantly looking for seams and space to move; by nature, the American army was a firepower intensive organism that chewed through the enemy with fearsome material superiority and front-width offensives. However, when opportunities presented themselves and delicious gaps emerged in the German position, the Americans could move faster than anybody in the business, with fully motorized infantry, fuel to spare, and an overawing air force that could extend combat support deep into the battle space.

The Germans would learn that, despite their vast experience and competence fighting mobile operations, this would be a dangerous game to play with the late war American Army. This was truly a case of “give them an inch and they’ll take a mile” - a small breach could quickly turn into a catastrophe given the latent American powers of mobility, especially when a hard driving commander like Patton was at the wheel.

Bradley Breaks Through: Operation Cobra

At this point, a quick editorial note and perhaps an apology is due. While the most well known and pivotal moment in the Anglo-American 1944 campaigns was the famous invasion of Normandy and especially the landings of June 6, it is not my intention to discuss them in great detail here. Our focus in this series has been on operational maneuver, and the D-Day landings do not fit this theme - they will feature in a subsequent series on naval and amphibious operations.

I think that it is probably not necessary to expend great energy on the landings at this point. While the scene on the beach is the most famous vignette of the war in the west - and in particular for Americans - it may come as a surprise that the landings were without question the easiest stage in the battle for Normandy. Only one of the five landing beaches (Omaha) was especially well defended (allied intelligence had failed to detect the presence of the German 352nd Infantry Division at Omaha), and the other beaches saw allied forces get ashore with relatively little difficulty. Contrary to the popular myth that the Germans failed to counterattack because Hitler was sleeping in, there was only a single panzer division (the 21st) anywhere in proximity to the landing beaches on June 6th, and its attempts to organize an adequate counterattack were utterly foiled by a mixture of allied air power and naval gunnery.

Thus, the events of D-Day itself were relatively drama free, from an operational perspective. In contrast to the usual impression of carnage (which was certainly real enough to the men who fought through it on Omaha Beach) the landings were achieved with only a fraction of the expected casualties, and a vastly superior allied force more or less swatted away the overmatched German resistance. In fact, apart from Omaha Beach, allied losses were shockingly light - over 150,000 men came ashore on the first day at a cost of perhaps 10,000 total casualties, of whom less than half were killed. Given the scale of this war, in which millions were dying annually, this was a small sum - and the shine of the victory was made even brighter in light of the fact that the Germans had been preparing their “Atlantic Wall” for nearly two years with pretensions of defending at the water’s edge. Instead, the German defense was bashed open in a single day with low allied casualties. This was a great victory.

The mood among allied command on June 7th, therefore, was much closer to euphoria than to gloom. The sense was that losses had been light and the time had come to build momentum. Instead, the allies ran into trouble almost as soon as they began to push out from the beach.

The initial German response to the D-Day landings was initially a bit scattered, largely because German planners expected the Allies to land at Calais, where they could seize an operational port. Even with allied troops pouring ashore in huge numbers, there was still some question in German brains as to whether Normandy was only a diversion. Notwithstanding these doubts, the nervous system of the Wehrmacht was still capable of lighting fast reactions, and by the end of June 6 there were already German units beginning to scramble into the battlespace, fighting fiercely. Within the first week the Germans had established a more or less coherent defensive line, and at no point did the allies threaten to immediately break out directly from Normandy into the open.

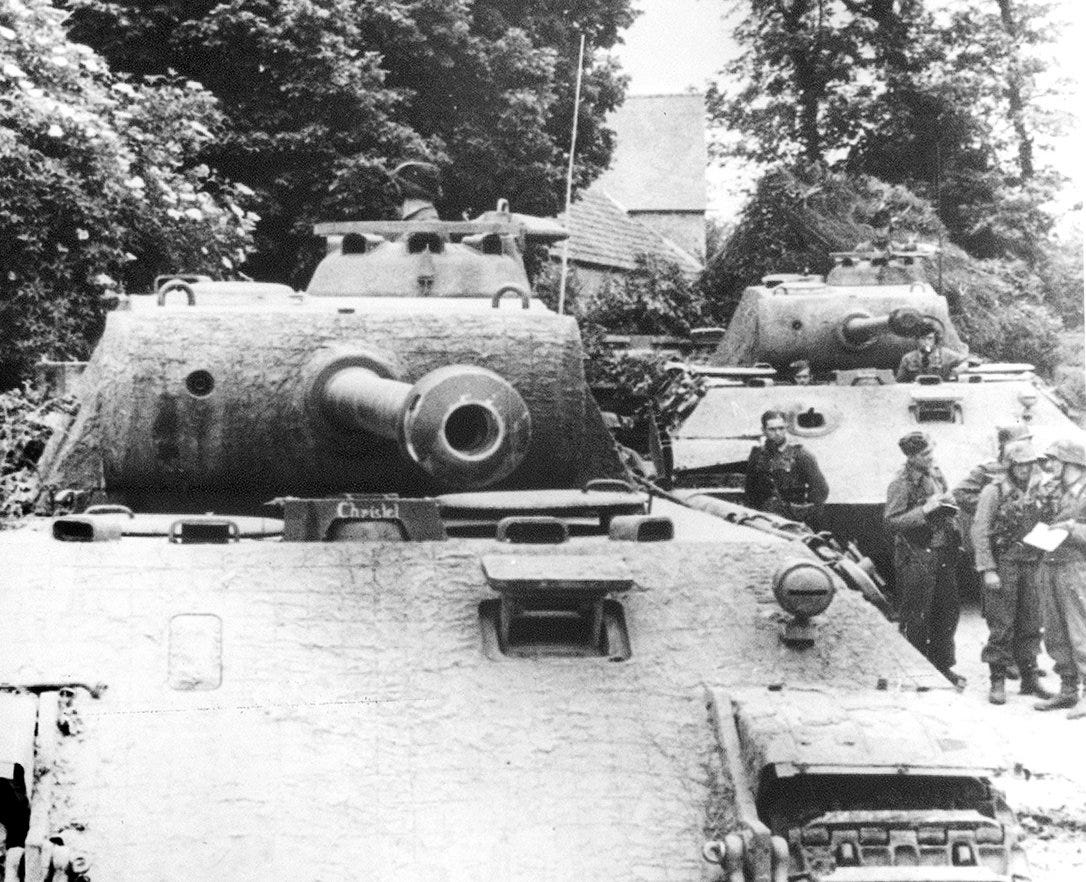

There were, of course, already signs that the brewing fight would not go well for the Germans. On paper, the Germans had an extremely powerful armored force in France - the Wehrmacht had, after all, chosen specifically to accumulate panzer assets in the west for the purpose of countering the allied landing. A comprehensive inventory revealed nine Panzer divisions and a single Panzergrenadier division, armed with some 1,400 armored vehicles. The tip of the spear was the 1st SS Panzer Corps, armed to the teeth with privileged access to new equipment and recruits.

On the tactical level, German Panzer forces - and especially the veteran heavy Panzer regiments with their Tigers and Panthers - were the best assets in the war, and therefore on paper the prospect of nine panzer divisions crashing into Normandy ought to have been terrifying to the allies.

Wars, however, are not fought on paper, and the Germans found it much harder to deploy to the front than the lines on the map would suggest. To begin with, the Panzer forces were scattered all over France, and rushing them all into Normandy would have been difficult even under ideal circumstances, which these certainly were not. The allies enjoyed total air supremacy from the outset, and this fact greatly complicated the movement of the German approach columns. Commanders were obliged to distribute their forces across a variety of different routes and do most of their marching at night. The mere sound of aircraft in the area was enough to make German columns bail off the road and take cover under trees, and everywhere there were wrecked bridges and shell-holed roads.

So while the Wehrmacht would have preferred - and indeed they tried - to rush their Panzers to Normandy and crush the Allied bridgehead, the arrival of German reinforcements was more like a trickle which could not get quickly organized for concentrated action, and most units arrived having already taken losses to allied aircraft along the way. To take but one example, the commander of Panzer Lehr Division, General Fritz Bayerlein, arrived in Normandy with his staff to discover that he was out of contact with both his Panzers (which were slowly dribbling into the area in dispersed columns) and his Corps commander, Sepp Dietrich, because Dietrich had also recently arrived and was still setting up his command post at some as yet unknown location. A General unable to either give or receive orders because he did not know where either his division or his corps commander were: emblematic of an army struggling to operate under a hostile sky.

German reinforcements trickling into the theater in a steady stream; allied forces coming ashore in ever greater numbers - a potentially combustible mixture, but the outcome satisfied nobody. Both forces at this point had ambitions of some sort of decisive engagement. The allies had notions of breaking out of Normandy quickly, and the Germans wanted to get forces in place quickly to counterattack and “drive them into the sea”, as the formulation went, but neither army could achieve what it wanted. Instead, German units arrived in theater too slowly to squash the beachhead (not that this would have been possible anyway, given allied naval artillery and aircraft) but quickly enough to wall the allies off in Normandy. Instead of breaking out to the south, the allies found themselves painstakingly carving out a position some 20 miles deep and 65 miles long.

The Normandy battlespace at the end of June had acquired a rather peculiar and quaint character, with a strange degree of symmetry. Two German armies had arrived on the line and now stood abreast across from two allied armies, locked in a positional struggle. On the west end of the line, German 7th Army faced the US 1st Army, and to the east 5th Panzer Army blocked the British 2nd Army.

It was at this juncture, as the front began to cohere, that the allied campaign was stymied by sheer rotten luck and oversight.

There had never been any particular reasoning that went into the allied deployment pattern, which had the Anglo-Canadian forces landing on the easternmost beaches and the Americans landing in the west. The assignment of the beaches had been simply an extension of the way that allied forces were arranged pre-invasion in England. British forces had been staged in southeastern England around areas like Dover and Brighton (indeed, many had been there since the end of 1940, in anticipation of a potential German cross-channel invasion) and the arriving Americans simply set up shop along the western part of the channel coast where there was room, nearer to ports like Dartmouth, Portland, and Poole. To avoid tangling up the invasion force, the assignment of beaches simply mirrored the staging in England, so that the Americans remained on the allied right (to the west) and the British remained on the left.

This seems all well and good - a simple practicality. However, the arrangement of the allied line proved to be of great consequence, because once they tried to push off the beach they discovered that there was nothing symmetrical about the terrain at all. On the allied left (the eastern, British zone), Normandy opens up onto an idyllic rolling plain, interspersed by small hamlets and the occasional orchard or tree line - in other words, the ideal terrain for mechanized operations.

Western Normandy, however, was the veritable opposite - a nightmarish patchwork of small farms and fields separated from each other by the legendary hedgerows. The latter are dense, intergrown hedges comprised of variegated trees, shrubs, bushes, and ivies, frequently planted on top of earthen embankments. While the term “hedge” may invoke the image of delightful topiary, in Normandy they were mighty tangles of plant matter some 10-12 feet high and several feet thick. In times of peace hedgerows have the dual effect of both fencing in the pastures and farmlands - conveniently marking the boundaries between properties and keeping livestock confined - and sheltering the fields from the wind. In 1944, however, the hedgerows served to compartmentalize the battlefield into thousands of tiny fortresses, ringed with dense shrubbery which could conceal firing positions, machine guns, antitank emplacements, and marksmen, and which were frequently so thick that even tanks could not easily pass through them.

Thus, while the British faced an open plain ideal for mechanized maneuver, the Americans on the allied right faced little more than an enormous siege and the prospect of endlessly trying to reduce German positions in small unit actions - a handful of squads, a machine gun and a mortar on each side, one field at a time.

The difference between the two sectors of front could hardly have been more stark. It can literally be seen on satellite imagery; western Normandy is a deep and verdant green, and close inspection reveals small pastures and fields latticed with hedges, while eastern Normandy is a tawny plain of rolling wheat fields. For all purposes, these were two entirely different battlespaces.

The problem for the allies was that they were deployed in the opposite of the ideal arrangement. The American Army was, for obvious reasons, the far more vigorous, rich, and powerful force. America was far richer and more potentially powerful than Britain in baseline calculations, and in any case Britain had been fighting the war for five years by this point, had taken far more casualties, lost far more material, and was generally running low on replacements and maneuver assets. This tended to make the entire British army increasingly casualty-averse, cautious, and tired.

Thus, the lower-energy ally - less able to take advantage of favorable maneuver terrain - was the one lined up on the open plain, while the ally with far more combat power and fighting energy was trapped in the hedgerow country, facing an excruciating positional battle. In contrast, the Germans did deploy their assets in something approximating an optimal way. The Wehrmacht rushed its premiere assets - the panzer units - to plug the open terrain to the east, putting a tired and apprehensive British force face to face with a wall of Panzer divisions.

The result of the disastrous allied deployment was an almost immediate stalling out of the Normandy operation and mounting casualties, with both Americans and British running into severe difficulties of very different kinds.

For the Americans, the problem was the unimaginable difficulty of slogging through the hedgerows, which afforded tremendous advantages to the German defenders concealed beneath the foliage. In contrast to our general impression of the Normandy beaches as the scene of the great drama, it was only after the Americans got off the beach and into the bocage (as the hedgerow country is sometimes called) that casualties began to explode - and explode they did. In the six weeks following the landing, frontline American infantry divisions suffered 60 percent casualty rates among their enlisted men and 70 percent among the officers. The worst damage, by far, was suffered by the 90th Division, which lost a whopping 90 percent of its rifle platoon personnel and endured a mind-boggling 150 percent casualty rate among its company grades (lieutenants and captains) - a number which essentially implies full attrition plus 50 percent losses among replacements. In total, the US Army took some 40,000 casualties in the weeks following the landing - a price which bought them a grinding, exhausting, infuriating advance of some 20 miles.

To the left of the Americans, the British had an equally difficult time, but for a very different reason. The British faced terrain friendly to the attack, but they shared the space with no less than nine panzer divisions which, in a word, soundly defeated every British attempt to break out. In particular, the British found that trying their luck in close quarters against the German heavy panzer battalions was a horrific idea.

The mismatch found its ultimate expression on the morning of June 13, when an entire British armored brigade found itself mixing things up in the little town of Villers-Bocage with Waffen-SS Lieutenant Michael Wittman of the 501st SS Heavy Tank Battalion. Wittman managed to take the British by surprise as they advanced up the road in a column - a pair of shots from his Tiger destroyed the lead British tanks and trapped the remainder on the road; Wittman and the rest of his company then drove parallel to the paralyzed column, firing as they went. Eventually, Wittman drove into the column, shooting several tanks and simply running over smaller vehicles. The Tiger shooting spree must have seemed like an eternity to the British warriors trapped in its fury, but the entire thing took less than fifteen minutes, at the end of which some 24 tanks, nine halftracks, and a few dozen trucks, cars, and guns had been destroyed by Wittman and his company.

This was a microcosm of the basic problem - the British could not cope with the tactical superiority of the elite Panzer units (which remained the best mechanized forces in the war, man for man and tank for tank), while the Americans had been tragically deployed in a secondary section of front characterized by impossible terrain. As a result, by the beginning of July neither allied force had captured its first major objective in Normandy (Caen for the British, St. Lo for the Americans).

Now, perhaps all of this may give the impression that the Germans were winning. They were not. The front had coagulated into a grinding, attritional struggle that cost the allies high casualties and slowed their advance. That much is all true. The issue was that the attrition cut both ways, and of course the Germans could not afford that burden in the long run. Even in the area around Caen, where the SS Panzer Divisions fought viciously and brilliantly and repeatedly defeated British attempts to take the city, the math was simply bad news for the Wehrmacht. These Panzer forces were, after all, the single most valuable asset still in the German stable, and here they were being used for positional defense. Even a successful defense was hardly consolation for the fact that the Germans were using their precious panzer divisions not for some decisive counterattack, but simply to hold a positional defense against an enemy with far more time, men, material, and firepower than they. This was a classic scenario in which a series of tactical successes adds up to an operational disaster.

Both the allies and the Germans, therefore, had a strong desire to unlock the front. The Germans wanted to restore mobility to the theater so that they could seek some sort of decisive battle, and the allies wanted to break out so that there might at last be room to fully deploy their superior fighting power. By mid-July, there was already a backlog of 250,000 men and a whopping 58,000 vehicles loitering in Britain simply because there was not enough room in the Normandy beachhead to deploy them.

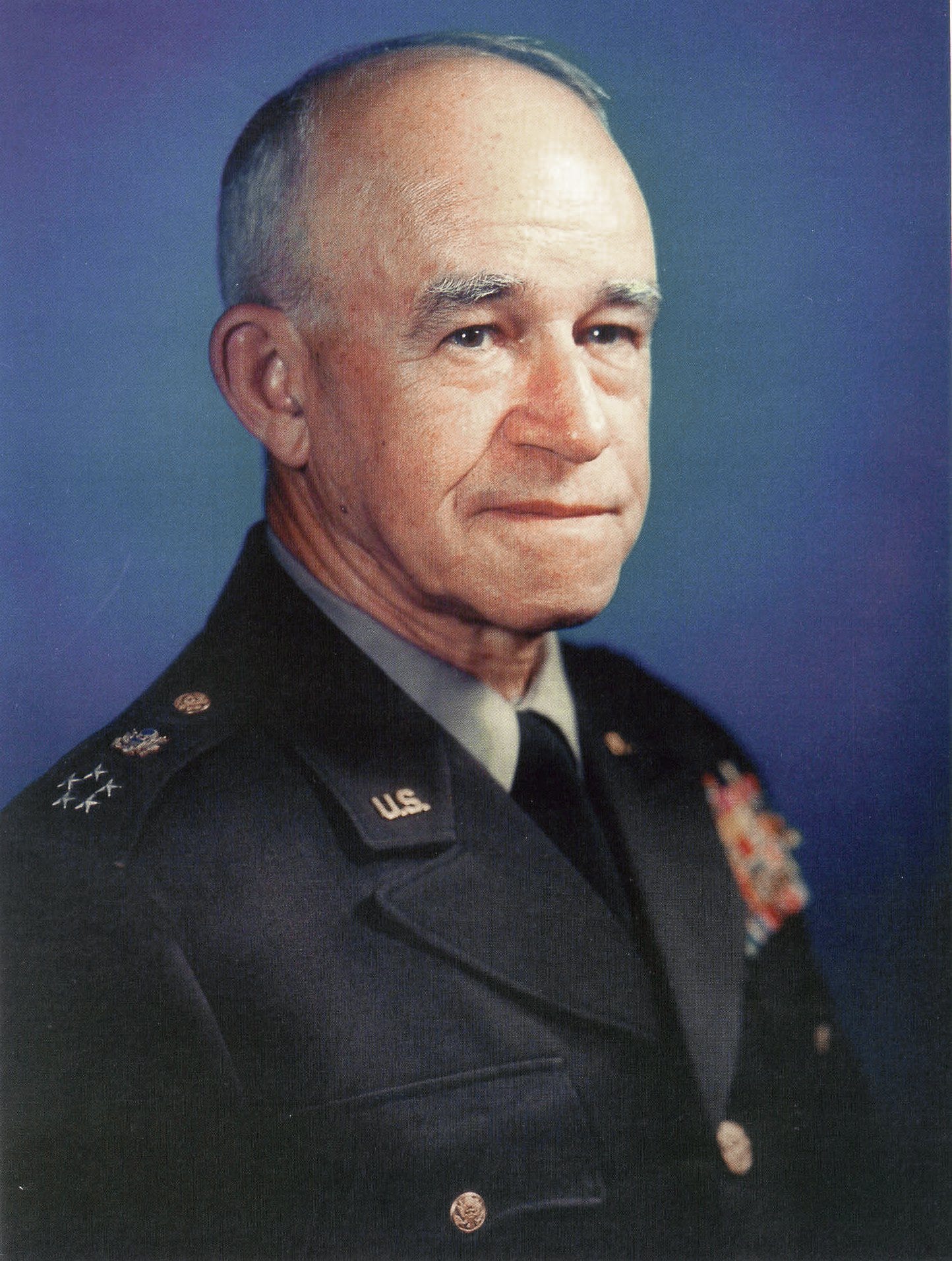

The task of solving this problem, on the allied side, fell upon General Omar Bradley, field commander of the US First Army. The solution that he landed on was rather fascinating, on a conceptual level, in that it combined the emerging motif of overwhelming American firepower with a concentrated and echeloned attack - in other words, an American version of Soviet Deep Battle.

Bradley resolved to select a narrow section of German front and crush it. The ensuing plan, named Operation Cobra, had two critical elements - namely, assembling a powerful, two-wave mechanized package, and planning an overwhelming aerial bombardment to pulverize the Germans in the sector selected for breaching. We can review the two elements in turn.

On the ground, Bradley organized an extremely powerful assault force, arranged in a way that would have been intimately familiar to Soviet planners. The first wave consisted of three infantry divisions, assembled on a very narrow front - 6,000 yards wide in total, or just 2,000 yards per division. Although labeled “infantry divisions”, the US Army (as we have mentioned) was able to equip these formations with a level of mechanization and firepower that far surpassed its competitors. The second wave, slated to exploit the breach in the German lines once it was opened, consisted of two armored divisions and an additional infantry division. Altogether, this six division package was designated US 7th Corps under General Joseph Collins, but in terms of fighting power this was essentially a full field army rather than a corps.

The arrangement of 7th Corps for Cobra looked virtually identical to the way the Red Army liked to stage for offensive operations, with two groupings - which the Soviets would have called Echelons - including a firepower-intensive breaching force in the first wave and a heavily armored and fully motorized exploitation force in the second wave. Bradley had, simply as an improvised battlefield expedient, laid the groundwork for the American equivalent of deep battle - but he would make it even more deadly, thanks to America’s uniquely unlimited ability to expend explosive ordnance.

The potent striking power of US 7th Corps was to be paired with one of the most awesome displays of airpower in the entire war, and indeed in history. Bradley had identified a 6,000 yard wide section of German front (a little under 3.5 miles). He now marked a rectangle around this sector on the map and asked the air force to absolutely plaster it with explosives.

Unfortunately, there was some controversy when it came to the bombing program.

The frontline essentially ran along the main east-west highway out of the town of Saint Lo, with the Germans and Americans glaring at each other from opposite sides of the road. This would be an extremely congested operating environment, not only on the ground, but in the air as well. The total strike package assigned for Operation Cobra included no less than 2,200 aircraft, including 1,500 heavy four-engine bombers. These planes would be asked to plaster a target area of only five square miles - affectionally dubbed “the carpet.” The potential for mistakes would be huge with so many planes airborne at the same time, trying to hit a small target that was only a few hundred yards away from American ground forces.

Bradley wanted to use the east-west road as a visual marker to reduce the potential for screwups. He viewed the road as a clear marker of the frontline that would be easily visible from the air, and he wanted the air force to fly parallel to the road, making their bombing runs on a west to east orientation. This would maximize their time over German positions and ensure that they did not overfly Bradley’s own assault force in its staging areas. The air force, however, was less than enthusiastic about this proposition - maximizing their time over the Germans also meant maximizing their exposure to flak. Bradley’s request for a parallel run was overridden, and the air force planned to approach the kill box perpendicularly - that is, flying over the top of Bradley's ground forces.

The start of the operation, slated for July 23rd, could not have been more ominous. As the enormous aerial strike force began to take to the skies, they spotted a storm blowing in and were recalled to base. One squadron of bombers somehow failed to receive the return to base order and began their bombing run, but they missed the kill box altogether and bombed positions of the US 30th Infantry Division. After waiting for the bad weather to clear out, Cobra was restarted on July 25th, and the first wave of American bombers once again released their payloads too soon and again bombed Bradley’s ground forces. In one of the more gutting twists of the war, this friendly-fire bombing killed the Commander of US Army Ground Forces, General Lesley McNair, who had gone to the frontline to encourage and inspect his boys. Thus, the highest ranking American officer to be killed in the European theater was killed by the US Army Air Force.

However, the bombers which accidentally dropped on their own positions were a tiny minority of the enormous Cobra strike. The great remainder roared over the designated carpet and began to transform it into a killing zone. A cloud of heavy, four-engine bombers - 1,500 in all - formed a death storm over the kill box and dropped a grand total of 60,000 bombs in the space of an hour: 1,000 bombs per minute, mostly 100 pound fragmentation bombs, every minute, without ceasing. Once the enormous bombing program had ended, Bradley’s ground force opened up with over 1,000 artillery pieces just to make sure the Germans were awake, and the tanks and infantry poured in. The enormous bombardment caught major elements of three German divisions - Panzer Lehr Division, 2nd Panzer, and 5th Fallschirmjager (airborne) - in an apocalyptic firestorm. Bradley had specifically requested the use of fragmentation bombs so that the roads would not be too cratered for his tanks and trucks to use, but the sheer mass of the bombing was sufficient to cause huge casualties and leave most of the German defenders completely stunned and incapable of resisting the ground assault.

The commander of Panzer Lehr Division, General Fritz Bayerlein, endured the American carpet bombing and gave one of the best accounts of what it is like to live through such an intense battering. There was no thought of resisting or taking any action other than hiding; he recalled looking to the sky and seeing the storm of bombers heading towards him, and then only a mad scramble as everyone ran for cover. The following hour was entirely disorienting, with zero visibility or communication possible amid the smoke, dust, and intense noise. By the time the bombing lifted, Beyerlein reported that his frontlines looked like the surface of the moon - “all craters and death” and he estimated that 70 percent of his personnel were either “dead, wounded, crazed, or dazed”. Little wonder that Panzer Lehr caved in almost immediately as Operation Cobra’s ground assault got underway.

After spending the first two days of the assault establishing and widening the breach in the German line, Bradley began to “insert the second echelon”, as his Soviet allies would have put it. The insertion of the American armored divisions into the battle on July 27 is the signal event which tore the German front wide open and put the US Army on a wild drive into the German rear. The following day (July 28) they captured Coutances and overran Panzer Lehr’s command post. On the 29th, they drove through Lehr’s repair shop - deep in what should have been the division’s rear area - and then out into open air. Normandy had been broken open.

It was during this hectic collapse of the front that General Bayerlein received a clichéd order that his division - which had essentially ceased to exist - had been ordered by the Fuhrer and Field Marshal Kluge to hold its position. Bayerlein’s apoplectic response entered the historiography as one of the few famous moments where a German general talked back:

Everything’s holding up front. My grenadiers and the pioneers—the antitank men—they’re holding. Not a single man leaves his post. Not one! They’re lying in their foxholes, still and silent, for they are dead! Dead, do you understand me? You may report to the Field Marshal that Panzer Lehr Division is annihilated… Only the dead are still holding the line, and I stay here as ordered.

Bradley had shown, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the US Army could create a breach whenever it wanted to. The American capacity to concentrate both maneuver assets and firepower could create a problem that the Wehrmacht simply could not solve. The hole was open, and it was time to drive through it.

And how did German high command react to Cobra? With their defensive front in Normandy torn wide open and a powerful American mechanized force pouring into the gap, surely the mood at headquarters was dour? On the contrary - in the face of an operational catastrophe, German command felt a grim sense of relief. They felt that they finally had the Americans right where they wanted them, but this time it would be the US Army that taught the Wehrmacht a lesson in the power of operational movement.

The Killing Field: Patton and the Falaise Pocket

The first weeks of August in 1944 were perhaps one of the most instructional vignettes for understanding the Wehrmacht - both the qualities that often made it lethal in the field and those that led to its inevitable defeat.

Certainly, there were any number of things to feel sorrowful about. Germany was facing total strategic overmatch on every front. The Luftwaffe had been chased from the skies and the German homeland was now exposed to relentless strategic bombing. Manpower and oil - the two pillars of industrialized war - were both at their limits. On the eastern front, the Wehrmacht had just suffered the greatest defeat of the war, with the entirety of Army Group Center swallowed up and digested into powder by the Red Army’s Operation Bagration. And now in France - the only strategic front that could even claim to have been quasi-stable - Operation Cobra had torn a hole in the line, and there was no reserve on hand to stop the leak.

Naturally, the Germans felt energized.

The German officer corps was trained to view warfare in a very particular way - a paradigm that shunned material intensive and costly siege warfare in favor of mobile operations and maneuver. The front had been blown open, yes, but this seemed to German eyes to present as much of an opportunity as it did a catastrophe, because it meant that the static siege in Normandy had been replaced by open and mobile warfare.

In fact, in the weeks leading up to Operation Cobra, the Germans had been seeking a way to break the front open and restore some sort of mobility to the fight. The problem they had was that their panzer divisions were all locked up in the defense, and getting them sorted out to attack required swapping them out with infantry divisions. Replacing large units in the line is tricky in the best of circumstances (which this was not), but the Germans were slowly but surely in the process of extracting Panzers from the frontline with the intention of concentrating them for a counterattack on Caen, with the objective of breaking through the British front and cutting into the allied rear, where they could threaten the vital allied airbases and landing infrastructure.

German plans for an offensive on Caen were preempted by Bradley’s big show at St Lo, and Operation Cobra forced a change of plans. Instead of an attack on Caen, the Panzers would be deployed to counterattack against the Americans.

Remarkably, there was a tentatively hopeful sense that the battle was shifting in Germany’s favor. This is because, by breaking the front open with Cobra, the Americans had restored a state of mobility and fluidity to the battle, and the Germans genuinely believed that they were genuinely much better in this sort of fight. In an attritional-positional fight for the hedgerows, the Wehrmacht simply could not hold up indefinitely against superior allied firepower and resources, but now that the front was moving again there was an opportunity for the Wehrmacht’s superior human factors (as they saw it) to play out - operational management, decisiveness, and aggression. One German military intelligence report stated, with a tone of optimism and without a hint of irony, that “the war of movement has begun!” Hitler’s headquarters went even farther, and proclaimed that the allied breakthrough represented a “unique opportunity” and that bold action could bring about “the collapse of the entire enemy front in Normandy.”

There was by now an entire field army bursting southward through the hole created by Operation Cobra - the newly activated US 3rd Army, under General George Patton (together with the US First Army, under General Courtney Hodges, Patton’s group formed the US 12th Army Group under the freshly promote Bradley). Patton’s legacy as a commander is somewhat muddled, partially because it is fused with his larger than life personality.

Patton was not a preternaturally brilliant operational mind, but he had one undisputed gift, and that was traffic control and movement. He was hard driving, and aggressive, and his obsession as a commander was keeping his legs churning at all times. Few commanders in history have been able to move as fast as Patton when he was off the leash, and in France, in the wake of Cobra, he was in his element. Astride a fully motorized force with bottomless gas, he began relentlessly funneling his units through the gap which now existed in the German line. By August 1, they had reached the critical town of Avranches, which lies at the “neck” of Normandy. In the following three days, Patton had somehow funneled seven divisions through Avranches, averting what could have been a titanic traffic jam by relentless ordering every unit to keep driving. For many of Patton’s men, their first view of their new general came at the roundabout at the center of Avranches, where Patton personally directed traffic with his riding crop, shouting his usual encouragements that they would kill the “goddamn bastards” and gut the “rotten sons of bitches.”

The gap that Patton was shooting was relatively narrow. On August 3rd, American forces captured the village of Mortain, solidifying a 20 mile opening between it and Avranches. This little bottleneck - for indeed, 20 miles was a short distance in the context of this war - was the gap through which Patton’s powerful mobile formations were now shooting, spreading out in all directions as they burst out of Normandy into the open of France.

Thus was born Operation Luttich. The concept was fundamentally very straightforward and in keeping with German operational sensibilities. In another context, the plan would have been “bold and brilliant”, as one German military intelligence officer later wrote. But this was no longer the Wehrmacht’s world.

Luttich ought to be very recognizable to anyone with a degree of familiarity with German operations. It called for all available panzer forces in Normandy (as well as some reserves hauled in from southern France) to be immediately concentrated into a strike group - Panzer Group Eberbach, under General Heinrich Eberbach - and launch an immediate counterattack on the Mortain-Avranches Gap. Slicing through the gap would put Patton’s entire Third Army out of supply, and put the Panzers in a position to then wheel northward and crash back into Normandy towards the allied rear.

In a different year, against a different opponent, Luttich might have been a smashing success. The German mechanized package retained its potency late into the war, and on the eastern front it was just this sort of decisive application of the Panzers that had repeatedly saved the Wehrmacht from desperate circumstances. France in 1940; Smolensk and Kiev in 1941, Kharkov in 1942 and again in 1943 - great victories across the breadth of the continent. Surely twenty miles was not too much to ask?

Reality has a way of intruding at inconvenient moments. On paper (a phrase which by now was becoming ominously familiar for the Wehrmacht) the Germans had nine Panzer Divisions either in Normandy or en-route from elsewhere in France, and Luttich called for all of them to be put under Eberbach’s command. But there were all manner of problems with actually getting this sizeable package staged. For one thing, many Panzer units were still defending in the line around the Caen sector and could not be rotated out in a timely manner. Their assembly area was on the eastern shoulder of the German front, which meant the Panzers had to move laterally behind the German line. Moving nine divisions at the same time in such a congested area would have been a traffic control nightmare during a peacetime exercise, and allied airpower turned it into an impossibility, with the Germans doing their now routine scramble to ditch off the road and throw on camouflage covering the moment they heard aircraft overhead.

Inevitably, an attempt to stage a strike force equivalent to a Panzer Army under these impossible circumstances fell far short of expectations. Eberbach’s nine division force ended up being four - only the 1st SS, 2nd SS, 116th, and 2nd Panzer divisions could reach their assembly areas, and these four were all far short of regulation strength simply because they’d all been fighting in Normandy for over a month. To make the math even more ludicrous, the commander of 116th Panzer Division - General Count Schwerin - could see that the Luttich was doomed and refused to participate on the grounds that it would needlessly waste his men. This was a rare moment of both loyalty and insubordination, depending on how one views it - undoubtedly insubordinate towards Hitler, but an act of loyalty and paternal care for his men. As a result of Schwerin’s stand, Eberbach’s assault - originally drawn up as a nine division power punch - ended up launching with three partial strength divisions, perhaps equivalent to a single full strength Panzer Division.

The results were predictable. Luttich became perhaps the single worst misfire of Germany’s war. The assault began around midnight on August 7 - by which time Patton’s army was already fanning out into the German rear - and initially put up the illusion of success. Allied aircraft were grounded by an overnight fog, and 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich managed to punch into Mortain, which was weakly held by the US 30th Infantry Division, who had only just arrived and were still setting up their command posts, road blocks, and firing positions. Taking the 30th unprepared and by surprise, it looked as if the Germans might build up some steam, but within 12 hours the entire fight had turned sour for the Germans.

There were three important reasons for this. The first - and for the Germans, most terrifying - was the midmorning dissipation of the fog, which let the allied air force rise up and efficiently smother the Panzer forces. The issue was not so much that a huge number of tanks were destroyed, but simply that they could not move and spent the rest of the day parked under trees and other cover. Secondly, the assault at Mortain was stymied by the heroic actions of US 2nd Battalion of the 120th Infantry Regiment. Caught out by the overnight German assault, the Battalion saw its command post (with their commanding colonel and all his staff) captured in the opening action and the remainder of the men surrounded. Totally cut off and out of command, the Battalion stood firm at their position on Hill 314 outside Mortain. Repelling multiple German attempts to knock them off their hill, 2nd Battalion used their perch on the hill’s peak to call in hyper-accurate artillery strikes all day. Finally, the Germans discovered that American infantry fought fiercely and effectively at their road blocks.

Luttich, originally conceived as a game-changing counterblow, collapsed into a debacle in a single day. With clouds of allied aircraft driving the Panzers off the road, American infantrymen doggedly defending critical road junctions, and 2nd Battalion - the so called “Lost Battalion” - sitting cozy inside the German operating area, watching everything from Hill 314 and calling down incessant artillery fire, the Germans simply couldn’t move. It is horribly difficult to wage a war of movement when one cannot move. By the end of August 7th, the German attack had firmly culminated, achieving perhaps 5 miles of headway around Mortain.

The following day (August 8), two signal events occurred. The first was that, rather predictably, German High Command doubled down on Luttich and decided to try a renewed assault on the Americans around Mortain. That same day, Patton’s 3rd Army overran German 7th Army’s command post at Le Mans. SS Obergruppenfuhrer Hauser and his staff escaped, but the geography was not looking good for the Wehrmacht. Patton had now driven far to the east of Mortain in a wide arc, and was coming up into the flank precisely as the Germans were banging away at Mortain to get westward. In essence, the Germans were straining to push their necks further into a noose precisely as Patton was tightening it.

The clock had started. A pocket was forming around the Wehrmacht in Normandy. As Patton’s third army rolled up in the east - reaching Argentan, well in the German rear - the other three allied armies on the line (US 1st Army, British 2nd Army, and Canadian 1st Army) began to press inward, bending the Germans into an ever more cramped compartment, even as Panzer Group Eberbach senselessly banged its head on Mortain. This was the Falaise Pocket - a unique form of hell on earth.

There had been plenty of pockets and total encirclements in this war, of course, but Falaise was unique in that it occurred in an incredibly cramped space under the overawing umbrella of allied air power. No other pocket or kessel in this war had so much explosive dropped on such a confined area, and that made it uniquely shocking.

Operationally speaking, Falaise was not perfect. In an infamous moment, General Bradley ordered Patton’s forces to stop their advance at Argentan, and await a linkup with the 1st Canadian Army, which was pushing south through Falaise as the northern pincer. However, the linkup never actually happened (1st Canadian could not completely break through the Panzer units still defending in the line) and so the pocket remained partially open, with an escape corridor that many Germans would eventually slip through.

Shortly thereafter, the story began to spread in America - begun apparently by a journalist embedded with Eisenhower’s staff called Ralph Ingersoll - that Patton had been ordered to halt because General Montgomery was envious of the glory and wanted British Commonwealth forces to complete the encirclement. Bradley was alleged to have stopped Patton’s advance as a sop to Montgomery. The story played on all the right chords of American wartime sentiment, which disdained Montgomery as a foppish, vain, and sluggish commander, and presumed that needless deference to sensitive British feelings only served to hold back superior American fighting men like Patton.

In fact, the failure to close Falaise was due to genuine military considerations. Patton’s leading units had advanced a long way in record time and were becoming increasingly strung out. Patton could surely have thrown a few infantry battalions out to block the exit from the pocket, but Bradley was worried (probably correctly) that the Germans would throw all their available panzers at these thin blocking forces in a breakout attempt. The simple fact that there was the equivalent of an entire German Army Group in the pocket, and Patton simply did not have enough forces out in the lead to solidly wall off the exit. Bradley’s later comment that he preferred “a solid shoulder at Argentan to a broken neck at Falaise” holds up to scrutiny.

In any case, the dissection of Falaise and the failure to close off the pocket entirely largely serves to distract from the reality on the ground. Falaise was one of the most totalizing and damaging defeats ever suffered in military history. Fully 100,000 German personnel were swallowed up, including no less than five Panzer divisions. While perhaps half of the Germans would escape through the 25 mile wide Argentan-Falaise Gap, they left behind the bulk of their heavy equipment.

As they seethed in the pocket, trying to organize some sort of extraction with the allies pressing in on all sides, the Germans were herded into one of the most appalling firebags ever witnessed. By August 18, the pocket measured only seven miles east to west and six miles north to south. This was an abnormally tight pocket, and it was raked nonstop by the unparalleled destructive power of the allied air forces and thousands of artillery tubes, with the beleaguered Germans under constant explosive assault by fighter bombers and shelling.

The German forces in the pocket remained relatively (and we stress this word) organized, simply because the entire command staff was trapped alongside the men. The units therefore remained operative, to a certain extent, and were able to sort themselves out to run the gauntlet of fire and attempt an escape. This is usually where military historians point out the high degree of “group cohesion” or discipline that let the Germans stay somewhat orderly inside the firebag, but this is only papering over a catastrophe. The allies had utterly crushed the Wehrmacht in Normandy. The Germans could not stand. By the time the last German survivors straggled out on August 21, they left behind a mass of corpses and wreckage so dense that it was unusual even by the standards of this war.

Eisenhower described the debris of Falaise this way:

The battlefield at Falaise was unquestionably one of the greatest "killing fields" of any of the war areas. Forty-eight hours after the closing of the gap I was conducted through it on foot, to encounter scenes that could be described only by Dante. It was literally possible to walk for hundreds of yards at a time, stepping on nothing but dead and decaying flesh.

It must be remembered further that the units shattered in the Falaise Pocket were those same divisions that had been incessantly chewed up over the previous month, making the climactic firestorm in the pocket the closing act of a decisive and exhausting strategic defeat. And what a defeat it was. From Falaise, it was almost a leisurely drive as the German occupation of France collapsed altogether. Within a week, the Americans were rolling up on Paris.

Operation Cobra and Patton’s subsequent explosion into the rear marked a stunning acceleration of the war, relative to the preceding slog in Normandy. From the D-Day Landings on June 6 to the start of Operation Cobra on July 25, it had taken the Americans 49 days just to reach St Lo - a midsized Normandy town just 20 miles from the beaches. Just 28 days later, on August 21, the Falaise Pocket was liquidated. Four days later, Paris was liquidated. The pace change was shocking - like a straining dam, the Wehrmacht had done everything to hold the water back for months, and when it burst it did so in astonishing fury.

The Germans should have been careful what they wished for. After all, it was they who had craved a return to mobile operations, and rejoiced at the resurrection of the “war of movement.” They got a war of movement - only it was the Americans that did all the moving.

Operations and Annihilation: Kluge, Patton

Viewed in the large collage of the Second World War, Operation Luttich can appear to be only a small and insignificant speck. We know the enormous, world changing campaigns - Barbarossa, Blue, Little Saturn, Overlord, and so on. What is Luttich - a five mile sputter by a few half strength Panzer divisions - compared to these enormous, continent-scale operations?

In fact, Luttich matters a great deal. In purely operational terms, it was significant - not because it gained results for the Germans, but because it ensured that the Wehrmacht shifted forces deeper into the Falaise Pocket at the same time that Patton was forming it. The decision to counterattack after the American breakthrough of Cobra, rather than preparing for a fighting withdrawal from Normandy, ensured that the allies were able to destroy the bulk of German fighting power in France right then and there. There would be no secondary defensive line on the Seine, or anywhere else in France - only a fiery and climactic defeat. It remains rather remarkable how quickly the allies were able to move on from Falaise to Paris and then right up to the German border, and Operation Luttich had a great deal to do with this.

But Luttich also matters as the archetype of German annihilation. Faced with total strategic overmatch, German generals remained obsessed with the idea of Operating - with maneuver as a panacea or silver bullet that could solve all their other problems. On the eastern front, Generals like Manstein constantly badgered Hitler for permission to Operate and move forces freely around the chessboard, completely blind to the larger context of Germany’s unfolding strategic disaster. In some ways, German officers were like a chess player obsessing over the optimal placement of a pawn, when the building around them is on fire and their opponent is aiming a gun at them. They continued to believe that some magic solution could be extracted from the board, but the chess game was over. So too the German Operations mania continued long after German had lost the ability to operate at all.

With Luttich, the planning staff naively drew up a maneuver scheme and planned an offensive in an act of willful ignorance. Wehrmacht personnel on the ground knew very well that they could not actually maneuver under the clouds of allied aircraft that roved the skies. They could not achieve strategic surprise, they could not assemble in secret or move unseen when the air was full of allied eyes, and they could not freely use the roads. The idea of maneuver, of a “war of movement” was an anachronism of yesteryear, when the Wehrmacht actually had the ability to move. Their prior experiences with the US Army in Africa and Italy had certainly taught them how impossible it was to Operate under allied aircraft and ranged fires, but the German officer corps was so trapped in its particular way of viewing war that it continued to pantomime Operations even as it was destroyed in every theater.

This was a systemic problem which plagued Germany from the moment their war began to go badly in 1941, in the expanse of the Soviet Union. From the moment of the first strategic failure, the only solution that the German officer corps had was to retool the maneuver scheme. They continued to seek solutions on the operational level, truly believing both that operations could make a difference in the context of total strategic suffocation and that they were unquestionably better in that domain; that superior German discipline, aggression, fighting cohesion, and decisiveness could overcome all of their enemies’ advantages. In the end, none of it was true. And with Luttich, the obsession with Operating ended in lunacy and the Wehrmacht learned that this was no longer their world.

They knew it, too. Field Marshall Günther von Kluge, Supreme Commander West at the height of the Normandy campaign, warned Hitler that given the low mobility of the Panzer forces and allied air superiority, “orderly conduct of the battle may be impossible.” But when the order came down to organize Operation Luttich, Kluge and his staff drew up the maneuver scheme anyway - and then, when the attempt to stage the necessary forces came up short and only three Panzer Divisions could be assembled, Kluge ordered the assault anyway. When it was clear after the first day that Luttich had hilariously misfired, Kluge ordered the assault to continue. Because Hitler ordered it.

And this raises a larger point. Luttich had one other connotation worth considering. The name of the operation was rather pointed. Luttich means Liege in German, and the operation was planned in the immediate wake of the failed July 20th plot to kill Hitler. In this context, the decision to plan and execute Operation Liege can be seen as a sort of re-pledging of loyalty to Hitler in the aftermath of an assassination attempt that provoked widespread disgust among the German officer corps.

What was the reward for this fealty? On August 15, as his army was being ripped apart in the Falaise Pocket, Kluge was removed from command. His crime, insofar as there was one, was coming under attack by allied aircraft, which raked his car en-route to a command conference and - although missing Kulge himself - destroyed his field radio.

Kluge’s brush with death put him out of communication for the better part of a day during a crucial stretch of the battle, sparking a fear at high command that he had gone AWOL. The Chief of the Wehrmacht Operations Staff, Alfred Jodl, even called Kluge’s chief of staff and asked him point blank if Kluge had defected, then dispatched Walter Model to replace him. Kluge knew that he was going to be scapegoated for the debacle, and on the way back to Germany he pulled off the road and swallowed a cyanide capsule. In his final letter to Hitler, Kluge attempted to clear his name with these words:

I take leave of you, my Führer—inwardly closer to you, perhaps, than you have ever suspected—in the knowledge that I have done my duty to the utmost. Heil, mein Führer.

And what was that duty? Drafting an insane operational order like Luttich and leaving an entire army group to be shattered in the Falaise Pocket?

This loyalty had transformed the German military institution into something monstrous. There is no denying that at the height of their powers, there really was nobody in the world that could Operate like the Germans, but by 1944 that world was gone. All that was left was the simulation of operation, which in reality became senseless acts of suicide that ballooned German casualties and winnowed the remaining ranks of the German youth.

The power to operate had now passed over in the east to the Red Army, and in the west to the ascending US Army, which had proven - emphatically, definitively - that the Germans simply could not withstand them.

And in particular, it would seem to have belonged to Patton, whose obsession with constant forward momentum, with grabbing the enemy and never letting go, would have been intimately familiar to many of the great names in the German pantheon of operators, for whom instinctive aggression and decisiveness were the foundation of victory. German fortunes had been forged by the willingness, or even enthusiasm, of their field commanders to march at high speed towards the enemy and then attack him immediately. Patton had this same instinct, and he was backed by a military apparatus far richer and more powerful than what remained of the Wehrmacht.

Surveying a field of burning grass, vehicles, and German corpses, Patton seemed practically invigorated by the acrid fumes. “Could anything be more magnificent?” He asked his aides. “Compared to war, all other forms of human endeavor shrink to insignificance. God, how I love it.”

Ironically, German leadership agreed with him. Trapped in a fight that they could not win, Hitler and his servitors increasingly searched for solace in the idea of glorious sacrifice. Luttich was part and parcel of an increasingly unhinged strategic direction that burned through divisions at a record pace - fortified places that were to be held to the last man, no-retreat policies, futile counteroffensives that threw units into the fire, and eventually a scorched earth policy within Germany itself. As the official German history of the war put it, “Readiness to die was raised to the criterion separating the worthy from the unworthy.” Ernst Junger, no stranger to this line of thinking, wrote that “Man’s deepest happiness is to be sacrificed, and the highest art of command is to show him goals worthy of sacrifice.”

Hitler believed that throwing millions of young men onto a funeral pyre would act as a sort of founding myth, or an act of transcendent inspiration for Germany’s future. One of his last written edicts - a dictation taken a day before his suicide - proclaimed:

Through the sacrifices of our soldiers and my own fellowship with them unto death, a seed has been sown in German history that will one day grow to usher in the glorious rebirth of the National Socialist movement in a truly united nation.

This was tragic, and it was all wrong. The enduring story from Normandy was not one of heroic German sacrifice, but of the ascendant power of the United States and the increasing swagger and competence of the US Army. Few people remember Luttich at all, let alone think fondly on the German soldiers who perished at Falaise. The only veneration to emerge from Normandy is that given to America’s “Greatest Generation.”

A bizarre pact had been forged, unspoken but fully understood, between the German army and the allies. The Germans would fulfill Hitler’s final wish and fight to the last man, to die in heroic embers, and the allies would kill them, happily playing the role of the antagonist in Hitler’s death drama.

“We got us a German who wants to die for his country. Oblige him.”

Big Serge’s Reading List

Cross Channel Attack by Gordon Harrison

Breakout and Pursuit by Martin Blumenson

Steel Inferno: I SS Panzer Corps in Normandy by Michael Reynolds

Normandy 1944: German Military Organization, Combat Power and Organizational Effectiveness by Niklas Zetterling

The Wehrmacht’s Last Stand by Robert Citino

Mortain 1944: Hitler’s Normandy Panzer offensive by Steven Zaloga

Victory at Mortain: Stopping Hitler's Panzer Counteroffensive by Mark Reardon

Falaise 1944: Death of an army by Ken Ford

Atlas of the Normandy Campaign: Maps and Aerial Photographs of D-Day to The Falaise Pocket by Michael Bechthold

Death of a Nazi Army: The Falaise Pocket by William Breuer

Normandy: From Cotentin to Falaise, June–July 1944 by Friedrich Hayn

There are not many people in this world I would like to meet to just to shake hands, if at all possible. Nobel Prize physicists are different but not comparable.

I was born during the end of WW II in occupied territory, the northern Netherlands, being liberated by Canadian and Tommies, the Amies going for some bridge near Remagen or something like that.

I grew up with the history of WW I and WW II and feel I have covered more history including military history than most. This summer, my wife and I cruised the Atlantic Coast of France, the second time for me. I still remember the pockmarked buildings in Caen from the early sixties.

Operation Market Garden is deeply ensconced in my generation and so is that 'Bridge Too Far. Working for the US Government in DC metro I wore the lanyard of the 82nd Airborne. No, I did not serve, I wore it to recognize the 82nd for the highest casualty ratio in their history, causing them to still have rubber raft boat races using real paddles every year in September in Fort Bragg NC, now Fort Liberty.

Visiting Normandy, I realized that there are a large number of German war cemeteries nearby the sizes of which dwarf the US cemetery near Omaha Beach, not an option on anyone's visiting schedule. The death count, not covered by anyone, is overwhelming.

I visited the Aberdeen tank display many years ago when it was still there, currently sitting in Richmond.

There is no one in your league as a military historian. I am grateful for everything you have written. Thank you.

Dear Serge, you seem to be one of the few to extract some wisdom out of that carnage that was the battles of WW2. Far too many analyses of engagements sound like Homer's catalogue of ships - just a boring (for the not initiate reader) compilation of forces and movements.

Your accounts instead are reflection and thorough analysis to actually grab the heart of the matter.

But to blame for that is also the peculiar state of historiography after WW2: the victor is far too often not very much interested in actual truth, the looser glosses over his failures and seeks someone or something else to blame.

The fact that the US sought the advice of - of all guys! - the german chief of staff Franz Halder to write the history of the war definitely blocked all real analysis for generations.