Among the many memoirs left behind by participants in the First World War, a ubiquitous motif is a profound sense of disorientation. The experience of the war was starkly different, depending on what node of the command hierarchy one inhabited, but enlisted men, officers, and political authorities all generally shared a sense that Europe was gripped in a death machine which had escaped the control of man. Humble infantrymen at the front experienced this the most acutely, in the intense physical disorientation that accompanied sustained bombardment by modern artillery, and also in the creeping spiritual numbness that accrued from years of siege in muddy trenches filled with detritus, rats, and corpses.

For officers in the upper echelons, the disorientation of the war was characterized less by the physical disorientation of the front and its endless cacophony of gunfire and explosions, and more by the breakdown of longstanding assumptions about how to conduct military operations, with operational planners groping in ignorance for solutions. In hindsight, it is easy to write off the brutal and ineffectual offensives (particularly on the western front), as an exercise in butchery and ignorance. In real time, however, the armies of Europe were attempting to solve tactical and operational problems which nobody had ever confronted before, and nobody scored particularly better on this test than anyone else, particularly in the early years of the war. Ypres, the Somme, and Verdun all blend together into a dissipated veil of death.

Given the apparent senselessness of these operations, the mass casualties that they produced, and the gridlocked nature of a front that moved very little over timeframes measured in years, it is easy to think of World War One as a fundamentally sterile and static conflict. This would seem to be as true at sea as it was on land, with the costly battlefleets of the combatants fighting engagements that were few, far between, and indecisive.

Nevertheless, if the war was relatively static on the operational scale, the immense strains of the war drove relentless experimentation. The Great War, while plagued by glacial fronts, positional combat, and intense attrition, saw the birth of new forms of combat which would become central to the conduct of later wars. These included Germany’s unrestricted submarine warfare against enemy shipping, innovative infantry tactics centered on small unit tactics and infiltration, and primitive variants of strategic bombing. It is impossible to tell the story of the Second World War without these concepts, and all of them were birthed in the seemingly static trauma of the prior war.

One of the Great War’s new forms of combat, which like the others would reach maturity in the second war, was the operational form that we know as the amphibious assault. The idea of amphibious operations itself was not new, of course - militaries had been using the sea as a maneuver space for the deployment of troops dating back to antiquity. One of the earliest battles that most people have heard of - the Battle of Marathon - began with a Persian amphibious landing in central Greece. Nevertheless, it was in the First World War that amphibious operations first took the form recognizable to modern peoples: landing an assault force against a prepared defense, in concert with naval support, with the intention of permanently holding the beachhead.

Like the great sieges of the primary European fronts, such seaborne operations were an entirely new combat problem, and complications abounded. Like virtually all other aspects of offensive combat in World War One, amphibious assaults were clearly an immature operational form, to the point where many interwar planners would draw the lesson that such assaults could not be successfully conducted at all. Of course, they were wrong, and amphibious operations became cornerstones of World War Two in a wide variety of theaters. Indeed, the single most famous American battle of all time, the invasion of Normandy, was conducted essentially along the lines pioneered in the first war. For better or worse, Spielberg’s unsparing treatment in the opening scene of Saving Private Ryan is perhaps the best known depiction of American combat.

Here we will trace the birth of this operational form, which was midwifed - like virtually all of the Great War’s military disasters - by a combination of strategic frustration, diplomatic imbroglio, hubris, and an overwhelming tactical nexus for which nobody had yet devised a solution. As Europe groped for solutions in 1915, some men, like the British First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, thought they had found one. Instead, they merely opened a new venue for slaughter in the place where earth and water meet.

A Brief Note on Amphibious Operations

Then God said, “Let the waters under the heavens be gathered together into one place, and let the dry land appear”; and it was so. And God called the dry land Earth, and the gathering together of the waters He called Seas. And God saw that it was good.

~ Genesis 1: 9-10

The sea has always been a combat zone for the warring states of the world, and one of the first privileges accruing to the state that holds sea power is the power to use the water as a maneuver space, to project combat power onto dry land across vast distances. This projection of power, by moving combat forces from the sea onto a hostile shore, what we call an amphibious operation, is one of the oldest combat tasks in the human experience, and one of the most perilous. One of the first battles in the general western consciousness, the Battle of Marathon, was an Athenian action to contest a Persian amphibious landing in Central Greece, and in the centuries that followed the Mediterranean frequently became a highway for armies sailing (and rowing) back and forth across the interior space of the ancient world.

The Great War, which began in 1914, marked a seismic shift in the nature of the amphibious combat task, which seemed to evolve overnight into something almost entirely new. The long history of amphibious combat had generally emphasized the role of the sea as a space for free maneuver, for the preferential landing of forces in unexpected or undefended places - in effect, using the long range and flexibility of seaborne transportation to outflank the enemy. In many ways, the entire point of seaborne force projection was to leverage its enormous range to land troops where the enemy was not.

The British, of course, were no strangers to this. As the world’s preeminent naval power over many centuries, few could boast such a vast experience moving troops to the dark corners of far flung theaters. The ability to deposit forces on the littoral had played a key role in Britain’s many colonial conflicts; in one of Britain’s most famous feats of arms, forces under General James Wolfe landed on the banks of the St. Lawrence River in 1759 and scaled the cliffs near Quebec, taking the French by surprise. That victory, which greatly accelerated the British acquisition of Canada, was punctuated by the famous last words of the French commander, Montcalm, who dismissed the amphibious threat by quipping: “It is not to be supposed that the enemies have wings so that they can in the same night cross the river, disembark, climb the obstructed acclivity, and scale the walls.” Indeed.

While the landing at Quebec was perhaps the most cinematic example of the operational form, it was hardly unique. In both the American Revolutionary War and the Napoleonic Wars, British control of the sea allowed them to deploy and support forces in theaters of their choosing. British control of the Chesapeake allowed them to penetrate inland from the American seaboard (leading directly to the burning of Washington DC in 1812), and in their wars against France they supported disconnected theaters of ground fighting in Iberia, including Wellington’s famous campaign in Spain.

All of this is perhaps interesting, but the key point from Britain’s long experience with amphibious operations was this: the benefit of sea control was that the sea became a maneuver space, by which forces could be inserted into advantageous positions to gain leverage over the enemy. Whether this took the form of a small scale venture, akin to modern special operations, as in the case of Wolfe’s task force scaling the cliffs on the St. Lawrence, or on a more strategic scale, like Wellington inflaming the Iberian front against Napoleon, the point was that, because the sea could allow you to insert forces at the place of your choosing, it could be used to outflank or avoid the enemy’s positions of strength.

In other words, the point of amphibious operations was certainly not to use the sea as a platform to launch direct assaults on enemy strongpoints. Even in the days of shot and sail, littoral fortifications, and especially proper forts, had intrinsic advantages over seaborne forces which were horribly difficult to overcome. Apart from the basic durability differential that accrued from a stone fort exchanging cannon fire with a wooden ship, forts enjoyed advantageous elevation and much larger and better protected magazines.

Therefore, in most historical cases where amphibious forces had to tangle with coastal strongpoints, they aimed to outflank the enemy by landing at a distance. This had been the case at the Siege of Louisbourg (1758) and the Battle of Beauport (1759). When Winfield Scott led the American invasion of Mexico in 1847, he landed his entire force several miles up the beach from the fortifications at Veracruz and then marched overland to assault it. This was considered an essentially textbook and idealized method for coping with a powerful coastal fortress. In the rare incidents where a direct assault from the sea was unavoidable, the results were frequently disappointing. In the 1797 Battle of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Horatio Nelson lost his arm leading a botched amphibious assault on Spanish fortifications in the Canary Islands. It was on the basis of this defeat that the famous saying was later attributed to Lord Nelson, although he almost certainly did not actually say it: “A ship’s a fool to fight a fort.”

What we are driving at with all of this is a relatively simple point: there was a great deal of experience with amphibious operations as such, but these generally aimed to use the sea as a maneuver space to deposit troops into undefended beachheads. In contrast, there was not an encouraging or systematic body of work that suggested that it was desirable to launch an assault from the sea directly into the strength of prepared enemy defenses. Even in more recent case studies, like the Crimean War, French and British naval forces had been unable to subdue Russian fortifications in places like Sevastopol and Petropavlovsk through seaborne assault, and the operations around Sevastopol transformed into a grueling overland siege that looked eerily like a preview of First World War positional warfare. In the American Civil War, likewise, naval power allowed Union forces to penetrate into the Confederate heartland via the great inland rivers, but was inadequate for a direct assault on the powerful defenses at Vicksburg, which was ultimately subdued, like Sevastopol, with overland operations.

When World War One broke out, the British were in the process of systematically studying such past examples of amphibious operations and considering how they could be applied to operations against the Germans. In January 1913, Winston Churchill - as First Lord of the Admiralty - tasked Admiral Lewis Bayly with studying the feasibility of using amphibious operations to seize an advance flotilla base on the Dutch, Danish, or Scandinavian coastline, which Bayly later narrowed down to the island of Borkum, some 18 miles off the German coast. Churchill then additionally tasked Bayly with studying the feasibility of a German force landing undetected on Great Britain, which remained a concern on the basis of exercises which had shown that it might be possible for a German landing fleet to reach the British coast undetected. Thus, when war broke out, Bayly was already in the process of evaluating the potential for amphibious operations in both directions - that is, of British landings on the far side of the North Sea, and of German landings in Britain.

On the basis of his analysis of past amphibious assaults, Bayly drew several important conclusions: namely, that feints and other methods of deception would be absolutely necessary to cover any potential landings, and secondly that the Royal Navy had to acquire specialized flat-bottomed landing craft. In effect, he had produced a feasibility study which, while it did not ultimately lead to any amphibious operations at Borkum or anywhere else on the North Sea coastline, did provide the first intentional sketch of future amphibious assaults. The theme was picked up by First Sea Lord Jacky Fisher, who advocated a landing on Germany’s Baltic Coastline.

However, systematic planning was undermined by the general sense of strategic paralysis which afflicted the British Navy in the first year of the war. No consensus emerged among the admirals as to where, how, or even if the German fleet ought to be drawn out for a decisive fleet battle, or how forward deployment of forces could be used to bring this about. Fisher was banging the drum for his Baltic option, and ordered a variety of landing craft and shallow draught gunboats, while others advocated offensive minelaying, submarine traps, and operations on the North Sea Littoral - there was even a speculative study of a raid to destroy the locks on the Kiel Canal. In short, there seemed to be practically as many suggestions as there were personalities involved. The general sense was that Britain’s seapower accrued immense operational flexibility and the ability to project combat power in any number of places, but there was little consensus as to how to capitalize on this. What mattered, however, was that the navy was already in the process of thinking systematically about amphibious operations, beginning with Bayly’s historical survey of 1913, when an opportunity presented itself in the apparently soft underbelly of the enemy.

The Decision for the Straits

The great military catastrophe that we know as the Battle of Gallipoli is something of a historiographical paradox. The reason for this is fairly straightforward. Because the decision makers responsible for Britain’s Dardanelle’s campaign were later compelled to defend themselves before an investigatory committee, an enormous amount of written evidence about the planning process was produced. Consequentially, the battle is one of the best documented incidents in military history. However, because those same defendants included a particularly verbose and famous individual named Winston Churchill, that same prolific body of evidence has been heavily colored by the energetic efforts of the aforementioned gentleman to clear his name. In particular, Churchill devoted an extensive word count in his six-volume history of the war to defending his decision making regarding the Dardanelles. Thus, the paradox is that when it comes to Gallipoli and the Dardanelles, we actually know a great deal about the campaign, but the things that we know are clouded by Churchill’s widely circulated version of the story.

To understand the military debacle that unfolded in the Turkish straits, we may as well go back to the beginning. Conveniently, the straits campaign can be ascribed a clean date of origin. On December 30, 1914, the British military attaché to Russia, Major General Sir John Hanbury-Williams, was summoned to the Stavka (army high command) in Baranovichi (modern Belarus) to meet with the Tsar’s cousin and Russian commander in chief, Grand Duke Nicholas. The Grand Duke informed his guest that the Turks had deployed a large army to the Caucasus which was now advancing across the front. The Grand Duke wove a thick cloud of melodrama, complaining that Russia had “been forced to deprive the Caucasus of the better part of its troops” in order to fight the Germans. He suggested, however, that “there were many places in the Ottoman Empire where any force brought to bear could broadly compensate for Turkish victories in the Caucasus”, and suggested in particular that a threat to Constantinople could be very helpful in this regard.

Without explicitly saying so, the Grand Duke was asking for a British diversionary attack against the Ottomans, and in a moment of remarkable diplomatic efficiency, this ad hoc meeting at the Stavka snowballed into full fledged operational planning in London in a matter of days. Almost immediately after concluding his meeting with the Grand Duke, Hanbury-Williams boarded a train for Petrograd, accompanied by Prince Nikolai Kudashev (the head of the Stavka’s diplomatic bureau). Upon arriving in the Tsarist capital, the pair met with the Russian foreign minister, Sergei Sazonov, and the British Ambassador, Sir George Buchanan. On New Years Day, Buchanan dispatched an urgent telegram back to the British foreign ministry in London asking that Britain contrive precisely such a diversionary operation to relieve the pressure on the Russians. The following day (January 2), the foreign ministry passed this request to Churchill (First Lord of the Admiralty) and Kitchener (Secretary of State for War). By the end of the day, Kitchener and Churchill had concluded that the only suitable operational schema was an assault on the Dardanelles.

The efficiency of this communication chain was breathtaking. The Grand Duke’s speculative and thinly veiled request for a diversion spiraled into serious operational planning in London in a matter of days. In a strange way, however, these discussions were moving so fast that they were outpacing events on the ground. It was precisely during those three days of urgent communication and discussion that the Ottoman Third Army was brought to the verge of total disintegration at the Battle of Sarikamish, presaging a decisive Russian victory on the Caucasian front. By January 2nd, the “urgent” situation in the Caucasus had been completely reversed, and the very premise of the Grand Duke’s request for a diversionary strike had become obsolete. This, however, had no meaningful effect on the planning process, which in just a few days had already taken on a powerful momentum of its own.

The reason was fairly straightforward. Even before the Grand Duke’s request for a diversionary strike, the British war cabinet was already thinking about where new fronts could be opened to evade the stalemate which had descended on the heavily fortified western front. While Churchill, at the time, was still an advocate of operations in the Baltic, other parties on the British War Council had already come around to the idea that the best way to undermine Germany might be to open a front against Turkey, particularly because Allied victories against the Turks might compel neutral Balkan states like Bulgaria and Greece to enter the war on the side of the Entente. A December 28th memorandum from Maurice Hankey, the secretary of the War Council, argued that “Germany can perhaps be struck most effectively, and with the most lasting results on the peace of the world, through her allies, and particularly through Turkey.” The Grand Duke’s request, then, served only to accelerate a discussion that was already happening in London.

Churchill, for his part, was initially skeptical about an operation against the Dardanelles, and in their initial discussions on January 2 it seems that he and Kitchener were thinking only of a demonstrative attack, rather than a real effort to break into the Turkish straits. However, in the two weeks that followed Churchill made an abrupt turn and became an energetic advocate of the emerging operation, and eventually the “owner” of much of the blame.

What happened was this: on January 3rd, Churchill wired Admiral Sackville Carden, commander of Britain’s Mediterranean squadron, asking bluntly if he considered “the forcing of the Dardanelles by ships alone a practical operation.” This was a crucial point, as in January 1915 the British had no troops to spare for a new land front of any real scale. To Churchill’s surprise, Carden replied that, while the Turkish straits could not be “rushed”, he believed it was possible to systematically break them open from the sea. Then, on January 7, Churchill received an intelligence report that the most powerful ship in the Turkish fleet had been put out of action for several months after hitting a mine. This was the SMS Goeben, a powerful German battlecruiser which had taken refuge in Constantinople and been “adopted” into the Turkish navy after being caught out in the Mediterranean at the outbreak of hostilities; in fact, the refusal of the Turks to evict the Goeben had been a proximate cause of Turkey’s formal entry into the war. Finally, on January 12, Jacky Fisher suggested to Churchill that Britain’s new super-dreadnought, the Queen Elizabeth, which was en route to the Mediterranean for gunnery trials, could participate in the operation and test her massive 15-inch guns on the Turkish fortifications. The availability of the Queen Elizabeth significantly improved the prospects, in Churchill’s eyes, given that the Mediterranean fleet (a deprioritized British command) consisted mainly of lighter battlecruisers and aged pre-dreadnought battleships.

The net effect of all this information was to completely change Churchill’s mind about the feasibility of a Dardanelles operation. He seems to have been surprised that Admiral Carden answered favorably about the prospects of breaking into the straits, and the sudden prospect of conducting the operation with greatly more favorable force ratios (that is, with the addition of the Queen Elizabeth and the subtraction of the Goeben) made a strong impression. Thus, on January 13, Churchill surprised everyone on the War Council by submitting a four point plan to force the Turkish straits from the sea. He concluded his proposal by arguing: "Once the forts were reduced the minefields would be cleared, and the Fleet would proceed up to Constantinople and destroy the Goeben. They would have nothing to fear from field guns or rifles, which would be merely an inconvenience.” Famous last words, but the operation was on.

Unfortunately, having started down the Turkish path, twin factors were conspiring to drive the British into a full fledged military disaster. First, diplomatic and strategic considerations forced the British into a naval-only assault on the Dardanelles by excluding other operational choices. Meanwhile, intense efforts by German officers working with the Turks were turning the Dardanelles into the single best defended and most professionally manned position in the Ottoman Empire. In other words, despite having enormous operational range and many choices, Churchill and his colleagues were unwittingly driving directly for the most impregnable Ottoman position on the map. All of these factors were independent, but they had a deadly synergy. We will review them in turn.

The Ottoman Empire had a vast littoral which was exposed to British naval power. In fact, at the time that the Dardanelles Operation first began to gain momentum, the British were already fighting the Turks in the Shatt Al Arab, and of course staring them down across the Sinai from the Suez Canal - and there were other potential places to open a front. In fact, Lloyd George (soon to be Prime Minister, but at the time Chancellor of the Exchequer) had suggested back in December that Britain might land forces on the Syrian coastline, where they could sever the Baghdad railway and slice apart Ottoman internal lines of supply and communication. In innumerable ways, this was a much easier prospect than forcing the Dardanelles, but diplomatic concerns precluded it.

The problem lay with the French, who had postwar claims on the region and were already greatly irritated with the question of command in the Dardanelles Operation. Per the terms of an agreement signed in August 1914, France had overall allied naval command in the Mediterranean, with Britain taking the reins in the North Sea, Atlantic, and the Channel. Yet, because the British would be committing the bulk of the force to the Dardanelles, Churchill insisted that Admiral Carden must have command, much to the chagrin of the French naval minister. In order to assuage French suspicion, Churchill had to pledge that the French would have command of any operations “in the Levant” (meaning Syria), and the British foreign ministry had to give an assurance that no British troops would be landed on the Levantine coast. Thus, the idea of severing Ottoman communications with an assault on the Syrian coastline - militarily, a highly sensible solution - had to be ruled out simply to keep the French happy.

It was not just the French, however, who factored into the decision to force the straits. The strategic concept had already escalated far beyond a simple diversion or demonstration, and London was now thinking about opening the straits to allow Russian grain exports to ship out of the Black Sea, and munitions for the Russian Army to flow in. The question of forcing the Dardanelles was also intrinsically linked with Britain’s Balkan policy. In early 1915, countries like Greece, Romania, and Bulgaria were still neutral, and it was greatly hoped that British operations against the straits could bring one or more of these powers into the war on the side of the Allies. In particular, the British had high hopes that Greek troops could participate in the operation and form the bulk of the ground force.

Unfortunately, Greek participation was ruled out by the Russians, who unequivocally vetoed any Greek contribution to the operation. The issue for the Russians was very simple: Constantinople (which they called Tsargrad) was the ultimate war prize for the Tsarist government, and they would not under any circumstances allow it to be taken by the Greeks. Sir Edward Grey had the unpleasant task of informing the war council that “the last thing the Russians wanted was to see anyone else making a triumphal entry into Constantinople.”

The Russians had the British over a barrel when it came to Constantinople. The city had to be unequivocally earmarked as a Russian prize in any postwar arrangement, to the point where the Russians threatened (on multiple occasions) to make a separate peace with Germany and simply drop out of the war if this condition was not met. This meant that the Greeks could not contribute ground troops, but the Russians were similarly unwilling to commit to provide troops of their own. There was a general sense that ground troops would have to be involved at some point - as Churchill pointed out at a January 28 meeting, even if the British fleet managed to force its way into the straits, “they cannot open these channels to merchant ships so long as the enemy is in possession of the shore.” Kitchener gave a vague assurance that he would “find the men”, whether in the form of Commonwealth troops from Australia and New Zealand, or the reserve 29th Division in England, but the idea was that ground forces would be made available only after the fleet had opened the straits.

This was a mess, but it is not hard to take the sum of all these factors. Churchill and Kitchener had set the British on the path to open a new front against the Turks, but the need to pacify French outrage ruled out any operations against the Levantine coast. The strategic import of opening naval traffic into the Black Sea further ensured that only a direct assault on the straits would do. Finally, Russia’s veto of Greek participation, Britain’s general lack of troops, and Russia’s own inability to contribute, ensured that there were no ground forces available to participate at the outset. Add it all up, and you get the Dardanelles plan: an attempt to break open the Turkish straits with a naval assault. Nelson’s apocryphal adage be damned. The ships would have to fight forts.

Unfortunately for the British, they were now on a course to attack the most formidably defended sector of the Ottoman coast. At the outbreak of war, the defenses on the Turkish straits were considered highly vulnerable, but much had changed since then. Russian intelligence had already ruled out an attack from the other side (against the Bosporus), noting that “the favorable moment for seizing the Straits has been lost.” This conclusion was, for some reason, not shared with the British.

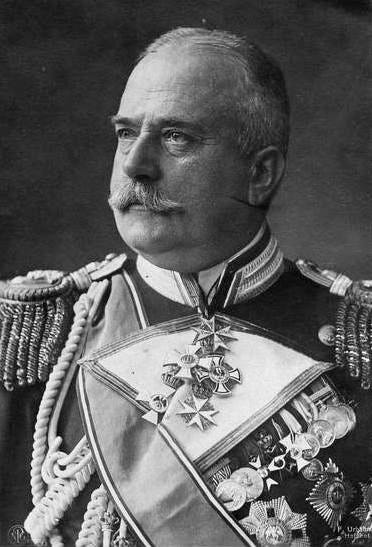

The critical development for the Turks had been the arrival of German Admiral Guido von Usedom, who was dispatched from Berlin in the autumn of 1914 to head up Sonderkommando (Special Command) Turkey, bringing with him a host of naval defense specialists, nearly 200 gunnery experts, and several batteries of heavy guns, including 14 inch Krupp models. In the months following his arrival, Usedom and his team conducted a major remodeling of the Turkish defenses: camouflaging guns, reinforcing casemates, erecting dummy batteries to draw enemy fire, and establishing eight mobile batteries which could deliver plunging fire on enemy ships and were very difficult for the enemy to target. The net result of all this was that the Dardanelles defenses, which in August 1914 possessed just twenty shore howitzers, now boasted 235 guns dispersed between fortifications and mobile batteries. Meanwhile, no less than eleven lines of naval mines, with a total of 323 mines, had been laid in the strait.

Furthermore, Usedom’s gunnery experts had been hard at work instructing the Turkish gun crews, instilling not only the requisite technical skills but also a thoroughly German sense of discipline. The Turks, for their part, profoundly impressed Usedom with their work ethic and rapid improvement, and he wired reports back to Berlin gushing about the great success bringing the Turkish gunners up to speed. Usedom then dispersed his German noncommissioned officers around the Dardanelles command, so that each gun crew had at least one German in it. While the British had a generally poor view of both the Turkish proclivity to fight and the state of the Dardanelles defenses, Usedom felt, with justification, that he had organized a motivated, disciplined, and schematically sound defense.

Taking the balance of all these factors, we get a fairly straightforward proposition. The British fleet (with a small French attachment) massed at Lemnos in the Aegean Sea was preparing to batter its way through a gauntlet of fortresses, augmented by mobile shore batteries, to clear the path for minesweepers to enter the straits and unblock the lane. No ground troops were initially available to assist the operation, although Churchill was holding on to vague promises from Kitchener that troops would be made available later, at an unspecified date for an unspecified purpose. The British did not seem to have an accurate assessment of the Turkish strength, or the many improvements that Usedom had made to the position. On the whole, strategic inertia had simply drawn the British into this course, with Churchill insisting repeatedly that the fleet could get through the straits on its own, while hedging his bets by maintaining that ground troops would eventually be necessary to fully secure the channel. All that was left was to give it a try.

The Dardanelles

The Dardanelles campaign began at 9:51 AM on February 19, 1915 with a farcical exchange of long range fire. The allied fleet which had massed at Lemnos was a formidable, if aged force. Admiral Carden had at his disposal a sizeable armada of 18 capital ships. Of these, the two hardest hitters were the brand new superdreadnought Queen Elizabeth, armed with eight 15-inch guns, and the battlecruiser Inflexible with eight 12-inch guns. The bulk of the fleet was comprised of pre-dreadnought battleships, twelve British and four French, armed with a total of fifty six 12-inch and eight 10-inch guns. This was hardly a fleet to rival the powerful British Grand Fleet or the German High Seas Fleet, which glared at each other across the North Sea, but for a secondary theater it was certainly an imposing force.

The Dardanelles defenses consisted of two critical zones. The more imposing by far was the section of the strait some ten miles upstream of the entrance, known appropriately as the Narrows. Here, the strait tightened significantly, so that it was less than a mile wide in places, and it was here that the bulk of the Ottoman firepower (and all of the minefields) were arranged. At the mouth of the Dardanelles, however, where the strait opens into the Aegean Sea, the passage was much wider (2.5 miles), and defended by a small cluster of forts: Seddul Bahr and the Cape Helles forts on the Gallipoli peninsula (the northern, European side of the strait) and Kum Kale on the southern, Asian side. All of these forts were of relatively archaic build (Seddul Bahr, for example, was a seventeenth century edifice), and modestly armed. All told, the Turkish emplacements at the mouth of the straits disposed of sixteen heavy guns and seven medium tubes.

Bearing in mind that Carden disposed of a significant volume of naval artillery, the results of the opening action on February 19 left much to be desired. Reducing the defenses at the mouth of the straits ought to have been the easiest phase of the operation, due to both the lack of minefields outside the straits, the relatively manageable size of the Turks batteries, and the fact that the allied fleet - firing from the Aegean - had a room to maneuver that would be sorely lacking once they progressed into the strait itself. The initial British attack, however, had little effect. Carden’s battleships, led off by the HMS Cornwallis, opened fire from extended ranges in the mid-morning and met no response from the defenders. The British ships were beyond Turkish ranges, but at such long distances it was impossible for the Allies to assess the damage that their opening salvos had done. At 2:00 PM, Carden closed to six thousand yards and fired again. Shortly after 4:00, the British finally came into range and the Turks opened up, with the British immediately pulling back. By 5:00 PM, Carden abandoned the attack and withdrew.

With the opening bombardment of February 19, Carden had wasted the element of surprise and fired 139 shells, which did virtually no damage to the Turkish batteries and killed only four defending personnel (two Germans and two Turks). The basic problem, as such, was that the defending batteries could really only be knocked out by striking the guns directly, but at long ranges the unspotted naval fire was woefully inaccurate against dug in targets on land. If Carden was hoping to open up the operation with a bang, he had failed.

With the element of surprise lost, Carden was now foiled by bad weather which forced a five day delay before he could attack again. As the fleet waited for the weather to clear, the British renewed their diplomatic offensive and sent out feelers to see if either the Greeks or the Russians wanted to get a piece of the action. The Greeks answered favorably, with the Anglophile Prime Minister offering three divisions to deploy to the Gallipoli Peninsula to provide a much needed land component for the operation, but the proposal was again scuttled by the Russians, who were playing a very effective diplomatic game. The Russians again categorically vetoed any Greek involvement, and counterbalanced this with a vague and non-binding offer to contribute an Army Corps which would get involved only after the British had forced the Dardanelles and destroyed the Turkish fleet. To make matters worse, Sazonov issued a threat (relayed through the French ambassador, Maurice Paleologue) that unless Russia was guaranteed Constantinople and the straits, he would resign. The meaning of this threat was clear: Paleologue informed Paris that if Russia’s demands were not met, Sazonov would be replaced by Sergei Witte, who was widely known as a Germanophile. Per Paleologue’s interpretation, Sazonov was essentially threatening that Russia would sign a separate peace with Germany unless she was guaranteed Constantinople.

The upshot of all this was immense strain on the British decision makers, who were being pressed on one side by Sazonov’s diplomatic offensive, and on the other by the surprisingly tenacious Turkish defense. On February 25th, Carden set back to reducing the outer forts and remained frustrated by the ineffectuality of gunfire. The British were only able to gain access to the entrance of the straits after landing demolition parties, which were able destroy several Ottoman batteries. This suggested, of course, that a mixed-amphibious solution would eventually be necessary, but as Carden’s entire ground complement consisted only of a few companies of Royal Marines, his ability to employ this strategy at scale was lacking.

Having broken into the mouth of the strait, Carden might have felt that he was gaining momentum. He was not. Once inside the straits, the British ships had come into the teeth of Usedom’s mobile batteries, for which they simply did not have a good answer. The problem was a basic matter of spotting. The mobile howitzer batteries, located at a good distance inland, could unleash “plunging fire” - high arcing shells that crashed down on the British ships - from firing points beyond the British line of sight, compelling the British to fire blindly back. British seaplanes, attempting to fly over the defenders to spot the batteries, were chased off by raking rifle fire. Meanwhile, the allied minesweepers (converted fishing vessels) now attempting to move into the channel served as veritable sitting ducks for the enemy howitzers.

At this stage in the operation, the crucial days of March 10-13 reveal the emerging British discomfort and the looming operational crisis. On March 10, Lord Kitchener at long last agreed to assemble a ground force to support the operation, which would be built around the 29th Division (to be dispatched from England a few days later) augmented by units of Australian and New Zealand origin which were now beginning to assemble on Lemnos. Although the belated decision to form a ground component, under General Sir Ian Standish Monteith Hamilton, was most welcome, it would not be available for many weeks, and its particular purpose was not yet clear. On March 12, Sazonov’s diplomatic squeeze (still directed mainly through Paleologue) finally paid off, and the British foreign ministry endorsed Russia’s postwar claim on Constantinople and the straits. Finally, on March 13 Admiral Carden and his second in command, Admiral de Robeck, reached the conclusion that their slow and systematic attempt to reduce the defenses was simply not working, and that “a heavy concerted bombardment and rush through the Dardanelles was to be considered.”

Taken together, it is clear that the British were on the verge of an operational crisis. On the one hand, Kitchener had finally agreed to assemble a ground contingent in Lemnos, which opened up a range of new possibilities. However, the accumulation of the ground force was progressing slowly, and it began at precisely the same time that the Naval commanders in the Mediterranean, particularly Carden, displayed fraying nerves and an increased sense of urgency. British planning was now pulling in two directions. Admiral Sir Henry Jackson, for example, counseled that the straits could not be forced in earnest until troops had been landed to clear out the enemy’s mobile howitzer batteries, while Churchill took the opposite approach and urged Carden to abandon “caution and deliberate methods” in favor of an aggressive push to “overwhelm the forts at the Narrows.”

Taken together, the second week of March ought to have been the moment for a systematic reevaluation of the operation. By signing off on Russia’s postwar claim to Constantinople and the Straits, Britain had essentially committed to expanded strategic goals which now implied the total defeat and dismemberment of the Ottoman state. Almost simultaneously, Carden and Churchill had come to the conclusion that their existing approach to systematically reducing the forts was not working, but somewhat surprisingly they did not seem inclined to amend their thinking based on Kitchener’s decision to organize a ground force. The unfortunate result was that the British opted to attempt a more aggressive push to open the straits with the fleet before the ground force was staged. This created immense operational confusion, particularly for the ground troops now beginning to accumulate in Lemnos. Hamilton recalled that Kitchener told him, rather unhelpfully, that “he hoped I would not have to land at all”, and that “he thought there was no great hustle.” In effect, the Army was forming a contingent on Lemnos under the rosy assumption that the fleet would succeed in forcing the straits alone, leaving Hamilton with the relatively easy task of mopping up and occupying a defeated Constantinople.

On March 17, the mood in the British camp had improved significantly. Hamilton had just arrived in Lemnos to oversee the assembly and preparation of the ground force, while the previous day Admiral Carden had resigned his post (citing poor health), bequeathing naval command to de Robeck, who was a much stronger and more aggressive personality. The general assumption, according to the War Council, was that a renewed naval attack would succeed in breaking open the straits, leaving Hamilton’s ground force available for “subsequent operations” of an unspecified nature.

The following day, March 18, began well enough, with a clear sky and a light, warm breeze dissipating the morning fog. De Robeck, energized by his new command, was fully prepared for what he expected to be the final push through the narrows. The plan, as such, was for a leapfrogging reduction of the Turkish defenses throughout the day. First, a line of the most powerful ships (including the Queen Elizabeth and the Inflexible) would advance into the narrows and destroy or suppress the forts from long range. Having silenced the guns in the forts, the second line of battleships would move forward to engage the smaller batteries on the shore and provide cover for the minesweepers to plod into the narrows and clear a channel 900 yards wide in the minefields. With the minefields cleared, the narrows would then be open for the battleships to advance to near point blank range and finish off the shore defenses. If everything went well, de Robeck expected to be through the strait, loitering in the Sea of Marmara and bombarding Constantinople the following day.

The attack commenced at 11:00 AM on March 18 and began much like the opening action of the campaign, with the first line of British ships bombarding the defenses from beyond the range of the Turkish guns. With no return fire coming from the shores of the narrows, it was difficult for the British to gauge the damage they were doing. It was clear that they had scored some strong hits on the forts, and just past noon de Robeck judged that it was time to dice things up at close range. He sent his second line (comprised of the four French pre-dreadnoughts) forward to see what they could do at more intimate distances, with his powerful first line trailing them and continually pouring on the fire.

It was at this point, as the battle spilled over into the afternoon hours, that things began to go horribly wrong. As the allied fleet finally pulled into range, Turkish guns opened up from both sides of the narrows, choking the channel with smoke, splashes, and splinters. Most of the Turkish guns were too small to do mortal damage to a well armored battleship, but they played havoc on the superstructures of the ships and confused the allied spotting.

A direct hit to the Inflexible’s fire control station, for example, sent fire and splinters streaming through the lightly armored post, which was perched high on her forward mast. Three men were killed and five wounded, including the battlecruiser’s gunnery officer, Rudolf Verner, who suffered a partially severed hand, fractured skull, a shattered leg, and a “pulped” arm. Retaining consciousness, Verner put on one of those remarkable displays of stoicism and bravery which often get washed out in the grand stories of war. He said “Thank you, old chap”, to a man who helped him lay down, then reported to the bridge: “Fore-control out of action. We are all dead and dying up here. Send some morphia.” Verner and the other wounded in the fire control station were eventually rescued, with Inflexible’s second in command suffering severe burns ascending the steel ladder to the post, which was scalding hot from the flames that now raged around the mast. These little vignettes - Verner politely asking for morphine, and a rescuer scorching his hands ascending a superheated steel ladder - are a poignant reminder that, for all the interest accruing to grand operational histories and designs, war is always the accumulation of innumerable human dramas which are life and death for those involved.

Worse still was the fate of the French battleship Bouvet, which was suddenly roiled by an enormous explosion at around 2:00 PM. The scene was practically surreal: in less than sixty seconds, she keeled, capsized, and disappeared entirely, taking her captain and 639 men down with her. Some 66 men were rescued (those that had been fortunate enough to be on or near the deck when the sinking began), who survived by running down the side and across the bottom of the ship as it rolled over, like hamsters on a wheel. Losing a battleship in the blink of an eye was bad enough, but for de Robeck and the other watching crews, the chilling element was that it was not clear what exactly had killed the Bouvet. Most assumed that a shell had penetrated into her magazine, but nobody had seen it happen.

The attack was misfiring badly. At 4:00, noting a slackening in the Turkish fire, de Robeck sent his minesweepers in. Their performance left much to be desired; having cleared a grand total of three mines from the first belt, they came under withering howitzer fire and retreated frantically back towards the entrance of the Straits. At 4:11, precisely as the minesweeping operation was collapsing, the Inflexible struck a mine near the Asian shore, in an area where no minefields had been expected. Now listing, Inflexible was forced to withdraw. The heavily bleeding Verner, still conscious, was transferred to a hospital ship to have his shattered arm amputated. He told the surgeon: “Tell my people that I played the game and stuck it out.” He died from his accumulated trauma a few hours later.

Shortly after the Inflexible limped out of the battle, Irresistible also struck a mine, but in her case the engine rooms flooded almost immediately, leaving her adrift. Her captain, notably, ran up a green flag which indicated that he believed he had been torpedoed. Fortunately for the crew, a destroyer was on station which allowed most of the men to safely abandon ship, but Irresistible was now left adrift. When HMS Ocean tried to pull alongside to tow the listless ship away, she likewise hit a mine and her crew were forced to evacuate.

It was at this point, as afternoon wore on into the evening, that de Robeck pulled the plug on the attack and withdrew. Of the twelve battleships that comprised his three main battle lines, three were now total losses (the Bouvet, which had sunk in such spectacular style, and the Ocean and Irresistible which were now drifting and abandoned), and three more were out of action, including the Inflexible and the French Gaulois and Suffren, both of which were partially flooded after taking hits near the waterline. De Robeck did have ships in reserve, but on the whole the action of March 18 had scratched off six of his eighteen capital ships. The worst part of all this, for de Robeck, was that he did not truly understand what was happening to his ships. Four of the lost or disabled ships (Bouvet, Ocean, Irresistible, and Inflexible) had apparently struck mines in places where they were not expected. Suspecting some sort of trick, he came to the conclusion that the Turks had devised a way to send floating mines downstream from the narrows.

In fact, unbeknownst to Allied command, the Turks had secretly laid an undetected minefield (the 11th such belt) under cover of darkness on the nights of March 7, 10, and 11. This minefield, very cleverly, was arranged much differently than the others. The first ten minefields in the Dardanelles were laid horizontally across the narrows (that is, perpendicular shore to shore) to block British access. The 11th, however, was arranged parallel to the Asian shore further up the strait, so that as the allied fleet came towards the narrows there was an undetected minefield to their right. It was upon this lateral minefield that all four of the aforementioned ships had fallen, striking mines as they attempted to maneuver under fire.

The attempt to crack open the straits had failed, and failed spectacularly. In enumerating the causes of the allied defeat, three distinct factors stand out, with important implications for future operations.

First and foremost, it had become clear that, although the firepower of modern naval artillery was extremely powerful, its use against land-based targets was limited in the absence of robust spotting and fire control. In the ideal use case, these guns were to be fired against other ships with an unobscured field of vision, with the open sea providing a clear horizon. The British had plenty of firepower, but they struggled to dial in accurate gunnery against concealed Turkish firing positions and especially against the mobile howitzer batteries which were firing “over the horizon” beyond the Allies’ field of vision. Although some efforts were made to provide spotting with aircraft and small landing parties, the communications and fire control of the day was simply inadequate for the task. In short, the British had very powerful guns which were frequently firing blind at targets they could not really see.

Secondly, the allied armada had woefully inadequate minesweeping capabilities. The minesweeping force consisted of 21 fishing trawlers requisitioned from the North Sea, with their civilian fishing crews assigned naval reserve personnel grades. Equipped with minesweeping arms and protected by improvised steel plates, the sweepers proved both skittish under fire and - even more importantly - unimaginably slow. In calm waters, they could sweep at a speed of 4 to 6 knots, but due to the gentle current that flowed out of the narrows, they could make no more than 3 knots when making their sweeping runs upstream, which is approximately the speed of a brisk walk. Furthermore, the draft of the converted trawlers was deeper than the lay of the mines, which meant they ran a constant risk of blowing up if they happened to bump an unswept mine. The makeshift armor, dangerous draft, and agonizingly slow speed combined to create a sense of intense vulnerability, particularly once they came under artillery fire. Perhaps, rather than wondering why they failed to clear the minefields, it is more appropriate to marvel that these civilian crews were able to make the attempt in the first place.

In short, therefore, the lack of accurate spotting prevented the fleet from successfully silencing the Turkish guns, and the inadequately of the sweeping vessels ensured that the mines could not be cleared, to the net effect that both elements of the Ottoman defense remained intact. When the dust cleared on March 18, only 9 of the 176 Turkish shore guns had been put out of action, and combined Turkish and German casualties were a mere 29 killed and 66 wounded. Finally, the third major intruding factor - the presence of an undetected parallel minefield running along the Asian shoreline - ensured that the failure of the allied attack carried an exorbitant cost, with these undetected mines claiming four battleships in the space of only a few hours.

Churchill remained unmoved, and expressed his belief that the Turks were running low on ammunition and that their morale was on the verge of breaking. The former point is debatable (the defenders were beginning to run short on shells for their biggest guns, but overall shell stocks were still healthy), and the second point is a farce. However, Churchill’s enduring enthusiasm for the naval-only attack plan was now a moot point. After conferring on March 22, de Robeck and Hamilton decided that the naval assault had categorically failed, and it was time for the army to get in on the action and destroy the shore defenses so that the sweepers could finally work in relative safety. The British would have to land on the Gallipoli peninsula.

Gallipoli

The Battle of Gallipoli was shaped in the first instance by a pair of nearly simultaneous discussions which occurred among the opposing leadership groups. On March 22, Admiral de Robeck hosted a small meeting aboard the Queen Elizabeth, which included General Hamilton (in overall command of the Mediterranean ground forces), Hamilton’s chief of staff, Major General Walter Braithwaite, and Lieutenant General Sir William Riddell Birdwood, who commanded the forces of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) which, along with the 29th Division which was still en route from England, was to form the bulk of the Gallipoli ground force. The conclusion of their discussion was twofold: first, de Robeck agreed that the time had come to scrap the naval-only assault and land troops on the Gallipoli peninsula; secondly, they decided against the more aggressive plan proposed by Birdwood to immediately land Anzac forces without waiting for the 29th Division to arrive. The net result, then, was a decision for a full scale joint army-navy assault on the peninsula which would necessarily be pushed out until mid-April (at the very earliest) in order to allow Hamilton to stage his full army group.

The timing, both of this British command conference and their proposed landing, was rather serendipitous, because it was just two days later, on March 24, that the Ottoman War Minister, Enver Pasha, summoned the German General Otto Liman von Sanders and offered him command of the newly formed Ottoman Fifth Army group for the defense of the Dardanelles and the Gallipoli Peninsula. Thus, after several weeks of letting the Admirals hash things out (first Carden and then de Robeck for the Allies, and Usedom for the Turks and Germans), both sides had decided almost simultaneously that it was time to let the Generals (Hamilton and Sanders) take over.

Liman von Sanders had extensive experience working with the Turks, having been appointed to head a commission from Berlin aimed at helping with Ottoman military modernization in the prewar period. Indeed, the “Liman von Sanders Affair”, as it came to be known, was a major friction point in the prewar diplomatic breakdown, with the Allies fearing German penetration into the Middle East. Notwithstanding the long relationship between the Turks and Liman von Sanders, it was no small thing for Enver Pasha to swallow his pride and give command of his best and most strategically critical army group to a German.

The Turks, however, had a good stream of intelligence which had tipped them off that a big amphibious operation was in the works, and Enver knew that the stakes were high. The intelligence aspect of the Dardanelles-Gallipoli campaign was rather unique, owing to the bizarre administration status of the British bases. The British had set up shop on the Aegean islands of Lemnos and Imbros, which were Greek territories. Notably, however, Greece had not taken possession of the islands (formerly longtime Ottoman holdings) until very recently, with the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913. What this meant, in effect, was that the British bases supporting the Straits campaign were on islands with sizeable Turkish populations, with the civilian administration in the hands of the neutral Greeks. The upshot of all this was that the British forces were essentially subject to persistent surveillance by local Turks, who were free to pass along what they saw to contacts in mainland Turkey. Enver Pasha was therefore fully aware that a sizeable allied ground force was assembling offshore in the Aegean, and that it was an appropriate time to swallow a bit of Turkish pride and give the Dardanelles command to the best man available, whom he judged to be Liman von Sanders.

In the aftermath of the Gallipoli Campaign, as we have previously noted, command decisions at every step were thoroughly autopsied and roundly criticized, and Hamilton’s choice of landing zones was no exception. A fair evaluation of the options, however, reveals that both Hamilton and Liman made essentially sensible decisions in a difficult situation.

The foundational fact to understand is that there were really only four suitable places on the “outer face” of the Gallipoli Peninsula which had terrain suitable for landing troops at scale. These were Cape Helles, on the southwestern tip of the peninsula; Gaba Tepe and Suvla Bay on the western face; and at the northeastern “neck” of the Peninsula, near the village of Bulair. Of these, the neck at Bulair was by far the most interesting. The neck of the Gallipoli Peninsula where it adjoins Thrace is very narrow, pinching to just under three miles wide at the narrowest point. A British landing here carried the obvious possibility of severing the peninsula’s connectivity to Thrace, which would cut off the bulk of Liman’s Fifth Army and trap it. Liman was acutely aware of this, and noted that a landing at Bulair could leave Fifth Army “cut off from every land communication.” This was not just a theoretical exercise for Liman - having established his headquarters in the town of Gallipoli in the center of the peninsula, he risked being cut off and trapped along with his troops. For Hamilton, however, there was a counterbalancing risk from the Bulair option: by landing his troops on the northern end of the peninsula, he would be exposing them to possible counterattack from the Turkish First Army, which was stationed in Thrace. Essentially, among the few possible landing spots in Gallipoli, Bulair and the “neck” was far and away the high risk, high reward option.

Knowing, then, that he needed to defend a few critical points, Liman chose what was an essentially sensible deployment plan, albeit weighted by a preoccupation with ensuring that the British did not cut him off at Bulair. Liman had six divisions at his disposal, two of which (the 3rd and 11th) had to be stationed on the Asian side of the straits to defend the forts. That left four divisions to defend the Gallipoli Peninsula on the European side of the Dardanelles. Liman opted to position one division (9th) at the southwestern tip, around Cape Helles, while holding two more (7th and 5th) at the northern end to defend Bulair, which he clearly understood to be the most sensitive spot on the map. That left his last division (19th, under the command of the future Ataturk, Mustafa Kemal) which he posted inland in the center of the peninsula, where it could be rerouted where it was needed as a sort of operational reserve.

The upshot of all this was that, among the possible landing spots in Gallipoli, the best defended was far and away Bulair. Cape Helles was adequately manned by the 9th Division, while Gaba Tepe and Suvla Bay were thinly manned, though Kemal’s 19th Division was in position to reinforce the defenses if needed. Ironically, Liman’s preoccupation with Bulair ensured that it was so robustly manned that Hamilton decided not to land there at all. Instead, the Allied landing scheme called for landings essentially everywhere else: French forces would land on the Asian side of the straits, the British 29th Division would assault five different beaches at Cape Helles, and the ANZAC forces would land at Gaba Tepe. Bulair would receive no landings, but a naval detachment would approach the shore to make a demonstration bombardment, hopefully fixing much of Liman’s force in place in anticipation of a landing that would never come.

Thus, criticisms of Hamilton’s landing scheme tend to miss the point. From a purely geographic schema, Bulair was certainly the best place to land, as it offered the opportunity to cut off all the Turkish forces on the peninsula and win the “big victory.” Since the sea was fundamentally a maneuver space in this campaign, critics of Hamilton emphasize his failure to leverage this mobility. Liman, however, was well aware of the vulnerability at Bulair, and had positioned two of his six divisions in the area, with the potential for additional forces scrambling in from Thrace. If the sea is indeed a maneuver space, in this instance it was almost certainly correct for Hamilton to use it to avoid the strength of the enemy’s defense.

In the Second World War, a nagging doctrinal disagreement lingered, centered on whether it was appropriate to support amphibious landings with preparatory naval bombardment. On paper, it obviously seems wise to soften up enemy defenses with heavy artillery fire, but skeptics argued that the results of such bombardments were not worth the downside of alerting defenders to the incoming landing. The Allies in the second war would try it both ways, at times applying a generous preparatory barrage, and at times attempting to gain the element of surprise by rushing the beach unannounced.

Gallipoli showed from the beginning why this debate existed in the first place, and why there was no cut and dry answer. As the allied armada approached the Gallipoli Peninsula in the early morning hours of the 25th, Admiral de Robeck noted that the night was “calm and very clear, with a brilliant moon.” Clear visibility makes it easier to oversee a complex landing operation, but it also helps the enemy. At 3:20 AM, a few hours before the first British troops made it ashore at Cape Helles, Turkish sentries from the 26th Regiment had already alerted command that the enemy fleet was approaching on the horizon. When the British naval guns opened up from extreme ranges at 4:30 AM, it was unmistakable that something big was coming. The troops that hit the shore at 6:00, therefore, ran into a defense that was essentially fully alert, with predictably deleterious consequences.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.