Author’s Note: This essay marks a direct continuation of a previous discussion of Germany’s 1942 campaign in southern Russia, which culminated in the Battle of Stalingrad. It is warmly suggested that you read this prior entry for context.

[They] constructed the largest and most complex military machine that has ever existed. It has been hammered and damaged to such an extent that it is questionable if it can ever be repaired. The supply, maintenance and administration of her retreating armies may already be beyond her capacity to control. We believe, therefore, that a situation may arise, and for which we must be prepared, in which [they] will be unable to stabilize and hold a line in Russia for any length of time at all. If that should occur, organized resistance in Russia might collapse.

A timeless assessment - usable in many contexts. But who said it, and of whom? It certainly reads like one of the overconfident predictions made by German leadership in the summer of 1941 during Operation Barbarossa - or perhaps it is a contemporary analysis by some talking head on cable news predicting the immanent collapse of the Russian army in Ukraine?

In fact, this was the assessment of the Anglo-American Joint Intelligence Committee in February 1943, after the Red Army’s world historical victory in the Battle of Stalingrad. The allies, which previously had fretted that the Wehrmacht would overrun the Soviet Union, now worried that German defeat was not only inevitable, but also that the Germans might be unable to wage a defensive campaign at all, and that the Soviets might win a rapid victory unfavorable to western interests. The whiplash is intense - a full 180 degree turn, from worrying that Germany was on the verge of conquering the USSR to fearing that the Red Army would sweep over Europe before the allies could get into the game.

Clearly, exaggerated and fickle doom-mongering has been around longer than we generally recognize. As Solomon said, there is nothing new under the sun.

Stalingrad is, to be sure, an easily identifiable turning point in the Nazi-Soviet War - marking, as we previously said, the first outright destruction of an operational level German formation and the end of the phase of the war where Germany held operational initiative and dictated the tempo and location of the fighting.

Yet in contrast to the melodramatic assessment of Anglo-American intelligence, which feared the immanent total collapse of the German Eastern Army, neither German nor Soviet planners were under any illusions about the fact that this war was far from over. Modern armies are, after all, unbelievably difficult to destroy outright, and even if the Wehrmacht no longer had any path to victory, it still had plenty of fight left in it. Purely in chronological terms, the Nazi-Soviet War was not even halfway over: by the time the Stalingrad pocket was liquidated at the end of January, 1943, a total of 588 days had elapsed since the Wehrmacht invaded the USSR, and there would be 830 more days of fighting before Germany surrendered. Nor, for that matter, had casualties reached their halfway mark.

Stalingrad was a turning point, yes, but one which left neither party room to contemplate its significance. The loss of the Sixth Army created a whole host of operational crises for the Wehrmacht, which left no time to sit around and mope; but neither could the Red Army sit on its laurels and celebrate - for the Soviets were planning an ambitious slate of even larger and more expansive follow up operations.

The irony of Stalingrad, then, was that although the battle is rightfully seen as a climactic moment and a discernable turning point in the momentum of the war, both the Wehrmacht and the Red Army viewed it as a subsidiary or secondary component of a much larger campaign. For the Wehrmacht, Stalingrad was an ancillary objective to a more expansive effort to capture the Caucasus, while the Red Army understood its counteroffensive at Stalingrad as only the first phase in a much larger plan to smash German Army Group South altogether. The deadly drama on the Volga, far from being a denouement, in fact only signaled that it was time for the pace to quicken.

To the Ends of the Earth: Edelweiss

As the German Sixth Army fought for its life inside the pocket at Stalingrad, their comrades four hundred miles to the southwest had a different set of problems. In Stalingrad, the war suffocated with its unbearable closeness - Russians across the street, through the wall, in the sewers, never more than a hundred feet away. This was a claustrophobic fight, brought to a fitting end in an ever shrinking encirclement, with the starving Sixth Army slowly squeezed to death by a closing vice.

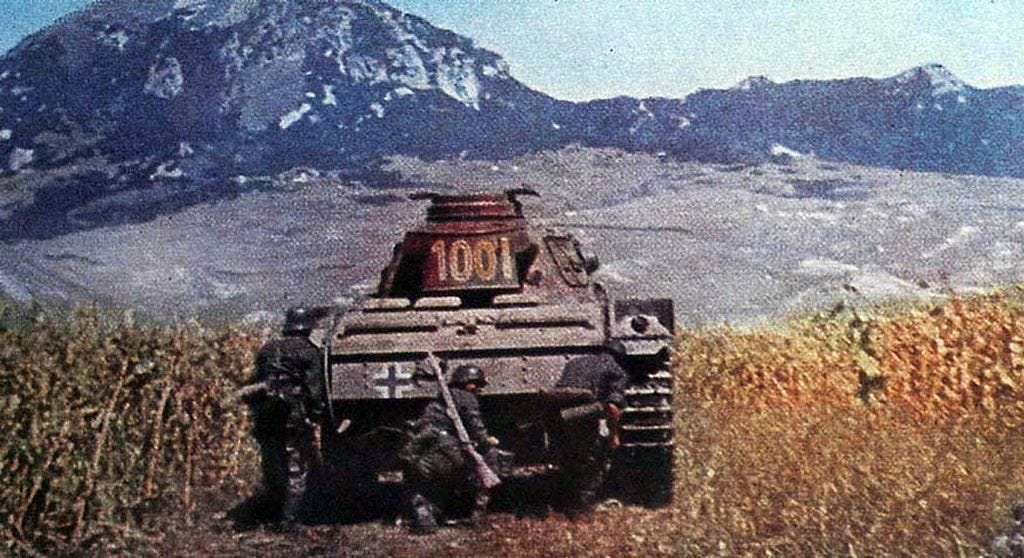

In sharp contrast, the German 17th and 1st Panzer Armies in the Caucasus were tyrannized by distance. This was Operation Edelweiss - fittingly named after a high altitude flower which grows on the slopes of the Alps, Edelweiss was to be the final stage of Germany’s 1942 lunge for the Soviet Union’s oil fields: an aggressive armored thrust into the Caucasus to seize the oil cities of Maikop, Ordzhonikidze, Grozny, and Baku. Whereas Stalingrad was an intensely compacted battlespace measured in blocks and buildings and rooms, Edelweiss presumed to reach objectives many hundreds of miles away across a vast mountain range.

The infamy of Stalingrad - and its apocalyptic scenery - has resulted in something of a reversal between operational priority and the narrative structure of the war. Almost everybody knows about Stalingrad; few know of Edelweiss. Yet in real time, Edelweiss was very much the primary operation, and Stalingrad the secondary. Stalingrad, in point of fact, was fought for the sake of Edelweiss; the drive to the Volga being conducted for the sole purpose of shielding the flank of the German thrust into the Caucasus (as we discussed at great length in the previous essay).

Although the drive into the Caucasus was construed as a sort of “final effort”, with the oil fields finally in sight, nothing about the operation was simple or modest. The Caucasus region was larger than prewar France or Poland, and the distances that the Wehrmacht needed to cover were significantly greater than the spaces covered in any of Germany’s early war operations. In fact, the distance from Edelweiss’s start line to its farthest objective (Baku) was 700 miles, making it the most geographically ambitious operation of Germany’s war - and the start line was already 1200 miles from home! The central feature of the region - the Caucasus Mountains - were by far the most difficult terrain feature that the Wehrmacht had yet attempted to navigate, and at the end of it all there were enormous cities like Baku and the threat of horrible urban fighting thousands of miles from home. Even the successful mediation of these obstacles and the capture of the oil fields threatened to create a complex engineering problem, as Germany would then have to devise a way to extract the oil.

Problems, problems, problems.

Like most of Germany’s operations in the war, what shocks the most about Edelweiss is how close it came to success. Loaded up with a pair of Panzer Armies and initially given top priority for fuel and truck transport, Edelweiss absolutely exploded off the start line on July 26. The Soviets were still in the process of establishing a coherent Caucasus front, and over the following two weeks Army Group South would storm across the Kuban Steppe, sweeping aside patchy Soviet resistance and pausing only to deal with a few engineering complications, like bridging rivers.

By August 10, the Wehrmacht had captured Maikop - the first of the three major oil cities identified as the objectives of Edelweiss, to be followed by Ordzhonikidze and Baku. Of course the oil fields had been thoroughly and competently taken offline by Soviet engineering, which not only destroyed all the above-ground extraction and refining gear but even poured concrete down the oil wells. So while the capture of Maikop did nothing to ameliorate German fuel shortages in the near term, given enough time German engineering could get the fields back online.

The Wehrmacht at Maikop represents what we might classically call a culmination point, far moreso than the Sixth Army at Stalingrad. In a little over two weeks, the Germans had driven 250 miles south from the Don and captured a major oil field, completing a critical operational objective. This was also the moment that the German strategic expansion, which had seemed so unstoppable for four years now, finally drifted to a halt like the ocean reaching high tide.

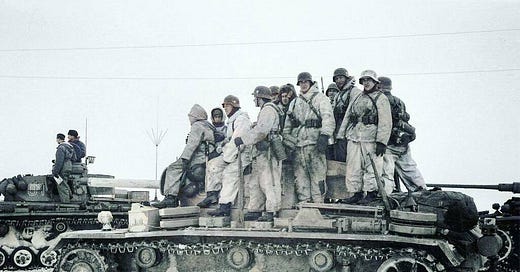

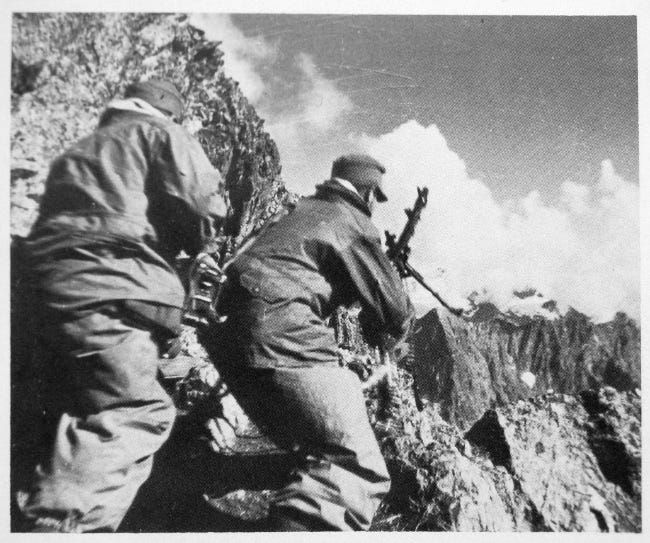

There were several problems. First and foremost, Maikop was the last stop before the flat and accommodating steppe gave way to the domineering Caucasus Mountains. Of course, it ought not to come as a surprise that operations in the mountains come with exceptional difficulties, but even so the Wehrmacht found it slow going. The sparse and crude roads made it a veritable nonstarter to bring heavy equipment up the slopes, and so the Panzers and motorized infantry had to give way to lighter formations like Jaegers and specialized Alpine units. The tactical difficulties are obvious, in that the rocky and forested crags of the Caucasus favored the defense by accommodating hidden firing positions and ambushes, but the problems with supply were perhaps even more aggravating - supply trucks simply could not reach forward positions, which meant virtually every bullet and every mouthful of food had to be taken either by mule or on foot to the front. All of this is to say nothing of the climactic extremes: the Wehrmacht fought in triple digit (Fahrenheit) temperatures and choking dust on the steppe in August, and in a snowy, high altitude freeze in the winter mountains.

The mountains were obviously a rather intractable obstacle to waging mobile operations, but the larger issue was that the German forces in the Caucasus were stripped of much of their fighting power right when they needed it. By late August, Sixth Army’s progress towards Stalingrad was stalling, and the response from Hitler and high command was to shift resources away from Edelweiss, including not only the entirety of 4th Panzer Group but also most of the theater air support - they even demoted the Caucasus group’s priority for fuel.

This speaks, once again, to the impossible choices facing the Wehrmacht. Every allocation of strength necessarily implied a denuding of fighting power in some other critical part of the front. There was not enough air power, not enough fuel, not enough Panzers, not enough of anything to wage such an expansive war across such astonishing distances. Hard driving Panzer crews, who had come so far, had to sit idly for days at a time awaiting fuel, loitering in the shadow of the mountains.

The Panzers slogged up the mountain roads, the Jaegers and Engineers and Alpine troops fought on the slopes, and once again the Wehrmacht came agonizingly close to its objectives. By the first week of November, the 3rd Panzer Corps had crawled to within two kilometers of Ordzhonikidze and the nearby oil fields at Grozny. Two kilometers. But like the battle at Moscow a year previously, the advancing force was simply exhausted, massively understrength, and straining to keep itself upright with a trickle of food and ammunition. And, like at Moscow, it had to fall back in the face of a timely Soviet counterattack.

This was an emerging theme - the Wehrmacht continued to set itself impossible operational objectives, come agonizingly close to reaching them, and then watch it all fall apart under the immense strain.

A few months later, on February 18, 1943, Reich Propaganda Minister Goebbels would deliver the most famous speech of his life at the Berlin Sportpalast. Now infamously known as the “Total War Speech”, the address for the first time acknowledged a sense of military crisis and called on the German people to intensify their commitment to the war and save Europe from onrushing Bolshevism. His famous line, “Do you want total war?” demanded a totalizing national commitment to victory, whatever the cost. War without limits.

The speech was several months too late. The Wehrmacht had already been waging war without limits in the Caucasus - not, perhaps, the moral and ideological limits implied by Goebbels, but a war blind to the limits of distance, material, and altitude.

In Operation Edelweiss, the Wehrmacht attempted something impossible. They began the year with an understrength army group and then prosecuted a busy summer operation in Case Blue, leaving the force further weakened and with a backlog of supply and maintenance problems. Then, with virtually no rest and dangling at the end of a 1,000 mile long supply line, they split that understrength Army Group in two and ordered two field armies (each of them half strength at best) to attempt a 700 mile drive, cross one of the world’s most difficult mountain ranges, and capture three major oil fields along the way.

Somehow, they captured one of the oil fields at Maikop and came within two kilometers of Ordzhonikidze. Two kilometers.

War without limits had long characterized this Wehrmacht, especially from 1941 onward - blind indifference to degraded fighting power, catastrophic supply problems, and tyrannizing distance, this was an army that continued to unload heavy swings at the enemy’s head, like an injured fighter running on pure adrenaline. And once again, the Wehrmacht had made it a frighteningly close run affair.

There was always this nagging question - just how far could an army get purely on aggressiveness, tactical proficiency, and willpower? It could get close. But not close enough.

Hardly consolation to the troops now strung out in the Caucasus fighting both bitter cold and Soviet forces, or to their commanders who had once again fought their way into a dead end, without the strength to go forward and unable to go back. They were nearly 1400 miles from home, with another 300 to go to get to Baku - but with the state of this army, Baku might have well been on Mars.

So many problems. How to get hot food to the frontline. How to move ammunition. How to get the oil wells at Maikop producing again. How to gas up the panzers. How to move forward. Problems everywhere.

And then, 300 miles to the north, the roof caved in at Stalingrad.

Deep Battle Unleashed

It was, at long last, time for the Red Army to make a powerful demonstration of its operational art.

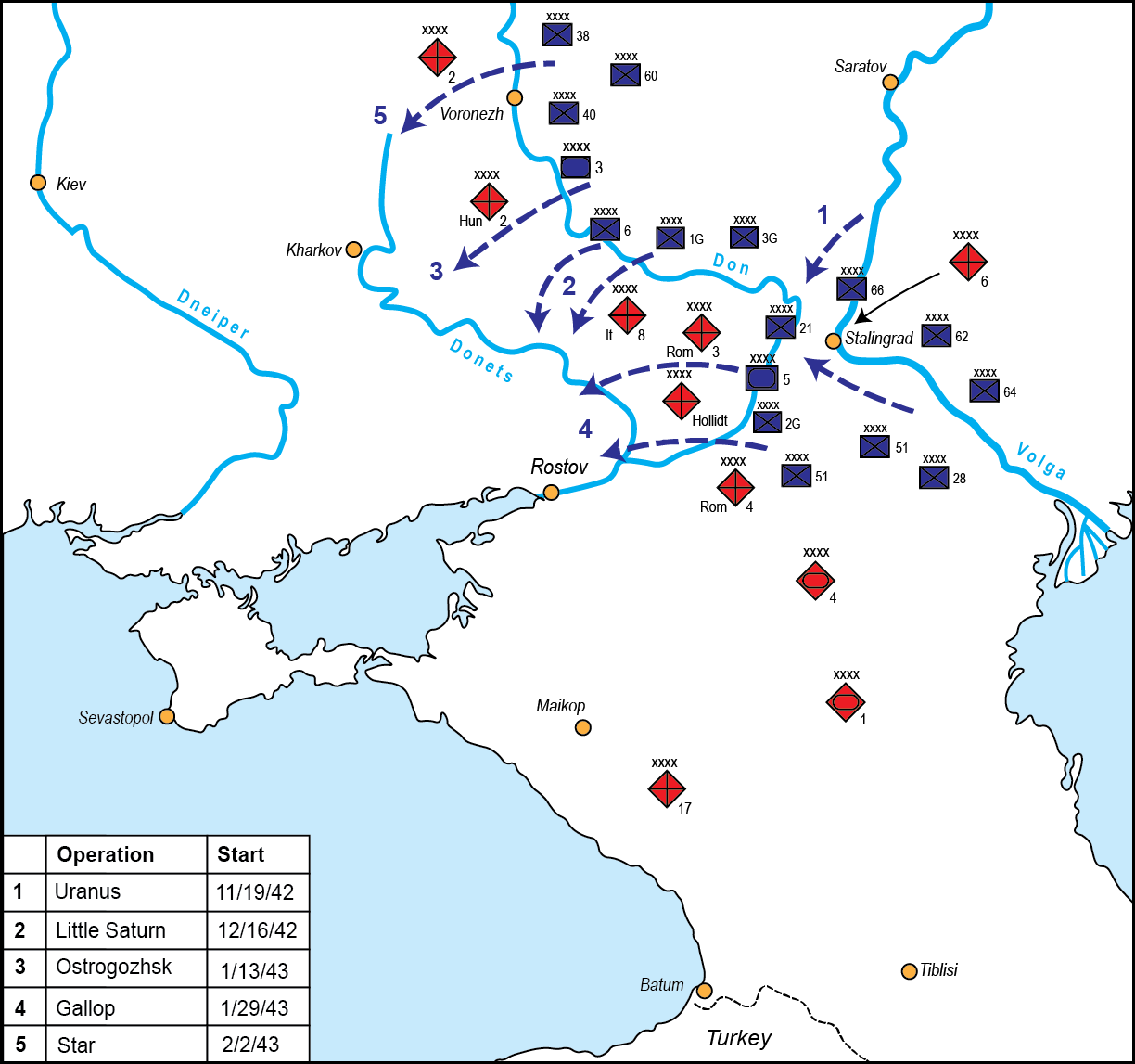

The encirclement of German Sixth Army had been a tremendous achievement and a great victory, but there was nothing about the operation that was particularly Soviet in nature - no special trademark signatures, if you will. Operation Uranus had been a fairly straightforward and obvious maneuver - two pincers smashing through the Romanian armies on the flank, meeting up at the Don River in the German rear. Lovely, clean, wonderfully effective, but this was not “Deep Battle” or any particular manifestation of the Soviet operational sensibility.

The unique quality of Soviet operational theory was not the use of pincers or encirclements. Lots of armies throughout history (and the Germans most of all) did this. The special Soviet ingredient was the concept of Consecutive Operations (sometimes called Sequential Operations) which emphasized the preparation of a series of assault packages that could launch one blow after another, hammering the enemy with a series of chained attacks. Modern armies had become so powerful and organizationally robust that it was impossible to destroy them in a single decisive blow (as the Germans had learned in 1941), so it was necessary to be ready to unload a series of coordinated punches, so that the enemy could not regain his balance and get back into a defensive stance.

In the early months of 1943, the Soviets at last found the perfect opportunity to demonstrate sequential operations. Operation Uranus had bagged the 6th Army, but this was just one of a series of operations which aimed to bag much larger prey. A field army was a fine catch - but what about destroying an entire army group?

The encirclement of German Sixth Army in November created a crisis for the Wehrmacht that went far beyond the simply loss of fighting power (a considerable blow in and of itself). Edelweiss had launched a large German force deep into the Caucasus, consisting of the entirety of 17th Army and 1st Panzer Army, the majority of 4th Panzer Army, and a variety of Romanian units that were in tow. The Soviet counteroffensive at Stalingrad now raised the possibility of a larger offensive to cut off the German line of supply and retreat and bag the entire operational group in the Caucasus.

The German line along the Don River was manned by units of variegated strength and national origin - from north to south, the German 2nd Army anchored the defense at the top around Voronezh; the Hungarian 2nd sat to its south, followed by the Italian 8th, the remnants of the Romanian 3rd, and then - a giant hole, where Sixth Army used to be. To plug this hole, the Wehrmacht created an improvised grouping - optimistically designated “Army Group Don” and rushed in one of their most gifted commanders to run it - Field Marshal Erich von Manstein. He was tasked with stabilizing the defensive front and - if it was even possible - counterattacking towards Stalingrad to rescue 6th Army.

This offers a useful opportunity to comment on the… shall we say, organizational liberties which the Germans increasingly began to dispose of. Manstein (probably the best overall German commander of the war) was nominally given command of a new army group - in theory, this was one of history’s greatest talents being handed a powerful bat to smack the enemy. But of what did this army group actually consist? As it turns out, not much at all.

Manstein’s new “Army Group” consisted on paper of three armies, but one of these was actually the Sixth Army - almost all of which was encircled at Stalingrad. So that left two armies, but one of these was almost exclusively Romanian and had little combat value. That left one army - ostensibly the 4th Panzer Army. Surely Manstein with a Panzer Army could do some damage! In fact, most of 4th Panzer had been previously split off and sent back to the Caucasus, and the portion left for Manstein had no Panzer divisions and consisted largely of… Romanians.

So Army Group Don, despite its lofty title, had virtually no organic combat power. Manstein was under orders to rescue 6th Army at Stalingrad, but he initially had no armor to speak of. In the end, he received a mere two Panzer divisions - the 6th (fresh off a refit in France) and the 22nd, which was transferred from the Caucasus and had a mere 30 tanks left in its inventory. These two divisions were used to launch “Operation Winter Storm” - an impossibly optimistic attempt to punch through the Soviet ring and reestablish a ground connection to 6th Army at Stalingrad. Predictably, the attack collapsed in only a few days.

And so Manstein, tasked with protecting the crucial sector of front connecting the German grouping in the Caucasus, was forced to fight with “Kampfgruppen.”

The Wehrmacht has been romanticized and mythologized in countless ways, and few are as bizarre as the idealization of the Kampfgruppe. Literally a “battle group”, these were improvised units that were increasingly used to deal with emergencies as the war turned against Germany. The Kampfgruppe is frequently romanticized as a symbol of a preternatural German inclination for warfare and a skill for improvisation. The notion is that the Germans could just throw together random units - a battalion of infantry, a few halftracks, a mortar, and a handful of assorted Panzers - and create highly effective and flexible units.

More often than not, the Kampfgruppen were ineffective and broke apart quickly. Usually, they did not even consist of proper troops and they were frequently commanded by officers who were not field commanders, but were put in charge because they happened to be available - logistics, personnel, and engineering officers, for example. The names on the German order of battle - “Gruppe Stahel”, or “Hollidt Gruppe” - vaguely conjure up the idea of stoic and experienced commanders leading gritty units, but more often than not these were rear area officers leading rear area personnel, like Luftwaffe ground crews, engineering units, military police, administrative staff, and the like - in short, men that were given rifles and hauled up to the front because the Wehrmacht was being defeated by the Red Army.

The contrast of these two armies could not have been more extreme.

While Manstein was trying to rescue Sixth Army with a pair of panzer divisions and stabilize the defensive front with combat ineffective Kampfgruppen, the Soviets prepared a sequence of operations that aimed to shatter the entire German line in the south and cut off the Caucasus grouping.

The operational agenda for the Red Army was genuinely impressive and spoke to an army that was fighting with increasing confidence. Operation Uranus had smashed the Romanians around Stalingrad and encircled 6th Army, and would be followed up by a series of similarly powerful attacks all across the Don River line. Each Axis army was to be targeted by a multi-Army offensive. The Italians were to be smashed by Operation Little Saturn; the Ostrogozhsk Operation would hit the Hungarians; Operation Gallop would attack westward across the Don against Manstein’s “Don” grouping, and finally Operation Star would smash the German 2nd Army near Voronezh.

These operations were to occur in a sequence, one after the other with little intermittent lag. This was to be a bona fide display of Successive Operations (or Consecutive/Sequential - pick your preferred terminology), which would hammer in a sequence along the entire German front. For an army like the Wehrmacht that had very little in the way of reserves, this promised a catastrophe, and if the Red Army reached Rostov they would cut off the entire German grouping in the Caucasus - a disaster that would have been a full order of magnitude more deadly than Stalingrad.

It should come as no surprise to anybody that the Red Army’s attacks broke through almost everywhere. Little Saturn began on December 16 and positively shredded the Italian 8th Army, which had no anti-tank weapons or armor to speak of. Many Italian units (somewhat stereotypically) either surrendered or fled without a fight. The Soviet 24th Tank Corps drove 150 miles into the rear in only nine days and overran a major Luftwaffe airfield on Christmas Eve. This produced one of the most cinematic scenes of the entire war, with dozens of German aircraft destroyed on the runways by Soviet tanks - some Red Army tankers rammed the tails to save ammunition. Overrunning an enemy airfield has always been a classical indicator that genuine operational exploitation has been achieved, and in this case it served as an iconic proof of Little Saturn’s great success.

January brought another catastrophe, with the Soviet Ostrogozhsk offensive beginning on the 13th and rapidly overrunning the Hungarian force, which consisted of only light infantry.

It is perhaps tempting to write this off as simply another instance of Germany’s allies being lightweights, but this would in fact be rather unfair. The German armies targeted by Operations Gallop and Star did not fare discernably better than the Hungarians and Italians did. The rather plain fact was that the Axis defense along the Don was overstretched, undersupplied, and completely overmatched by the enormous force that the Red Army had assembled. It was little wonder that the Soviets put up one of the most substantial operational successes of the war.

By the middle of February, the Red Army had advanced all along a front nearly 350 miles long from north to south, and most importantly they had gone deep - nearly 300 miles, in some places. Major industrial cities were recaptured in short order - Voronezh, Kursk, Belgorod, Kharkov. Since the start of Operation Uranus in November, no fewer than six axis field armies had been either destroyed outright or mauled to the edge of disintegration. Most importantly of all, the Red Army seemed poise to not only reach Rostov (cutting off the German Caucasus grouping) but perhaps even drive to the Dnieper - destroying Army Group South in its entirety.

Little wonder then, that it was precisely at this time that Anglo-American Joint Intelligence issued their warning that German forces in Russia might collapse altogether.

Deep Battle, and more specifically Sequential Operations had been a smashing success of the highest order. The Red Army had as recently as October been defending along the Volga, but they’d caved in the German line on the Don, crossed the Donets, and now the Dnieper was in view! At which river would they stop? The Bug? The Vistula?

The Rhine?

The crisis faced by the Germans was proportionate to the elation of the Red Army. A whole line of armies had crumbled, Edelweiss was stalled out, the Caucasian grouping faced entombment in the mountains if they failed to get moving soon, and the entire southern theater was collapsing.

To try and restore this appalling situation map, Army High Command took the discombobulated order of battle, with its disjointed, strung out, half-strength army groups - “Group A”, “Group B”, “Group Don” - and merged them back into a single command as Army Group South. This command was given to Manstein, along with a simple objective: save the army.

Manstein had always fancied himself a genius in the vein of Moltke or Napoleon - gifted with both the preternatural aggression of the classical German school, a precocious intellect and deft command of operational realities, and that ethereal ability to see things, to extract truth from the map, to know and act and win. Most of his colleagues, enemies, and historians agreed, however begrudgingly, that he was probably right. He was the architect of the world historic victory over France, and his solo command in Crimea had been an amazing success. No one could deny it: Manstein was talented. Perhaps he was even a genius.

It would take a genius to save Army Group South.

Manstein’s Immortal Maneuver

The Field Marshal glowered at the map. Problems everywhere. He finally had what he had wanted from the very start. Full theater command - carte blanche and a whole army group. Well… it used to be an army group. Now it was just a mess. There were two Panzer Armies in the inventory, but they were way out in the Kuban, far south of the Don. He had to get them out of there, somehow. The Hungarians and Italians had melted away. That much was to be expected, he supposed, but it still left a gaping hole in the center of his front, and the Soviets were plowing through it - heading for the Dnieper. If they reached the river… Something had to be done. 2nd SS Panzer Corps was arriving in theater. He could do something with that. There was some real fighting power. And the two Panzer Armies in the South. Yes… there were enough pieces here to achieve something. They just needed to be brought into position. Somehow.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.