Perhaps no battle or operation in the Second World War has the same level of name recognition and infamy as the great battle at Stalingrad in the waning months of 1942. This battle, more than any other, became the archetype of apocalyptic urban combat and the potential for modern war to become a senseless charnel house. Fighting for months in the ruined and smoking remains of a wrecked industrial city, combined casualties of the two contesting forces would swell into the millions. Stalingrad presents a visceral image of grey skies, endless rubble and ruin, and grim death. For the warriors who actually fought the battle, the Volga river may as well have been the Styx.

Stalingrad attains further notoriety from its role in the narrative structure as the identified turning point of the war. Whatever arguments may be made about whether such a turning point actually exists, Stalingrad certainly represented a clear shift in the momentum and progress of the war, particularly in the sense that it marked the irretrievable loss of strategic initiative for the Germans. After Stalingrad, the Wehrmacht was increasingly unable to attempt the sweeping offensive operations that had previously characterized its war, and the Germans found themselves irreversibly on the back foot. Stalingrad also marked the first time in the war that a major German field army was lost wholesale - destroyed, in just the sort of annihilation battle that the Wehrmacht had long been inflicted on its enemies.

Between the foreboding, ominous, and widely identifiable impression of Stalingrad as the unparalleled urban apocalypse battle, and the undeniable sense that the battle represented a momentous pivot in the course of the war, it is perhaps less fashionable to think about the battle as an operational contingency - a mere chance, or even an accident. The battle was apocalyptic, massively violent, and historically significant - this much is clearly undeniable. Yet it is equally true that Stalingrad itself was nothing less than an instrumental objective for both armies - certainly, nobody set out in 1942 with the intention of fighting over this unremarkable and drab city.

Indeed, it is rarely understood why, exactly, this city was so viciously fought over. There remains a myth (which seems impossible to eradicate) that the city became a battleground because it was named after Stalin. The idea that Hitler wanted to embarrass Stalin by capturing his namesake retains eternal allure, because it allows Hitler to be reduced to a childish simpleton, destroyed by his own petty hubris. Tempting, perhaps, but also untrue, and representative of the worst sort of history for children.

Stalingrad became the scene of unprecedented carnage as a result of the organic development of a large-scale German operation in the summer of 1942 - an operation which never initially identified Stalingrad as a target. Nobody in either the Wehrmacht or the Red Army anticipated that the city would become the locus of one of the largest and most bloody battles in world history, and this is perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of the battle. While Stalingrad will always retain its cachet as the blood soaked turning point of the war, for us it offers a fascinating window into the way that operational dynamics can seemingly have a mind of their own - two armies can become trapped in a death pit at a place where neither of them expected or wanted to fight.

Strategic Context: The Global War

In many ways, the operations of the Wehrmacht in the early months 1942 can seem like merely business as usual for an army that had unparalleled proficiency on the operational and tactical level. Indeed, one could make the case that - after the horrors of winter warfare - spring arose on a German army that was back to its old ways. In May, two of the Wehrmacht’s most celebrated field commanders won major victories - Erwin Rommel in North Africa at the Battle of Gazala, and Erich von Manstein in Crimea - (we examined both battles in an earlier entry). These operations were soon followed by a major German victory at Kharkov, which destroyed a large Soviet tank force.

Operationally, this was indeed business as usual. All the by now familiar motifs of the Wehrmacht’s craft were on display, and the German mechanized package seemed to have lost none of its potency. Perhaps some officers could convince themselves that the setback at Moscow had been only an aberration; a speedbump on the road to victory.

Yet, above the operational level, on the geostrategic plane, Germany faced an emerging catastrophe. The final failure of the drive on Moscow had coincided with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and Germany now faced not only a continental scale land war with the Soviet Union, but also a global conflict with the enormously powerful Anglo-American bloc.

This created a broader strategic peril where active fronts threatened to metastasize rapidly, dispersing German forces and preventing a timely resolution in the east. Of course, it is clear (as I have argued before) that Germany did not actually have a viable path to victory over the Soviet Union by this time, but if the Anglo-Americans began to activate new fronts the diffusion of German energies would make the outcome a foregone conclusion.

In the near term, however (that is, at the beginning of 1942), American power was only just beginning to mobilize, and Germany appeared to be winning in North Africa. There therefore appeared to be a window of opportunity where the the Wehrmacht still had strategic initiative and could concentrate the great preponderance of its combat power in the east. It was therefore possible to plan a large operation in the Soviet Union in 1942, but this operation had to be designed to improve Germany’s ability to shift to a strategic defense in the coming years.

In the long run, it was clear that the entry of American combat power would cost Germany the strategic initiative and force a full-spectrum strategic defense of the Nazi empire in Europe. The “optimistic” scenario for such a defense, which still existed in early 1942, was based on a few key strategic assumptions, as laid out in a series of Wehrmacht memorandum.

These assumptions, upon which Germany rested all its hopes, were as follows:

Germany could achieve its critical military objectives in the USSR and in North Africa before American fighting power could be mobilized.

German victory in Africa and the Soviet Union would induce Turkey, Spain, Portugal, and Sweden to join a continental defensive bloc, granting Germany the ability to control the naval lithosphere around Europe.

Japanese operations in the Pacific would maintain their momentum and force major Anglo-American force commitments in that theater, preventing America from conducting a full scale two-ocean war.

As events happened, all three of these assumptions proved to be not only unrealistic and unfounded, but laughably so.

Yet they are extremely instructive. We must strongly note (for this is of great importance) that in early 1942, much of Wehrmacht leadership still believed that the war with the Soviet Union was a sort of appetizer, which would be won as a preliminary condition for waging a global war with the Anglo-Americans. The land war in the east, in other words, was something that needed to be resolved so that Germany could be freed to wage a full strategic defense of Europe by land, sea, and air - using the resources of the defeated Soviet Union to power this long war effort.

This, of course, demonstrates that Germany was asking the wrong questions and thinking about the wrong problems. They were concerned with bringing a resolution in the east so they could move on to the (as they saw it) bigger problem of contesting Anglo-American global hegemony. They did not yet seem to realize that they were being defeated outright in the east. So eager were they to move on to the main course, they did not see that the appetizer was eating them.

So, what to do? Clearly, the attempt to destroy the Soviet Union in a single campaign had failed badly, but there was still time to bring operational resolution in the east and establish a stable position for strategic defense. This implied that, even if it was now deemed impossible to destroy the Soviet Union outright with a heavy blow, the Wehrmacht must contrive a way to at least cripple the Red Army. This would entail not only the destruction of major Soviet forces, but also an attempt to cut off the Red Army from its oil resources. It was perceived, then, that a badly mauled and de-mechanized Red Army could be dismantled and finally defeated at leisure in the future.

An April directive from Hitler commanded the Army to “destroy what vital defensive strength was left to the Soviets and, as far as possible, to deprive them of the most important energy sources for their war effort.”

Easier said than done.

Get the Oil: Case Blue

Understanding the operational design and subsequent maneuvers that brought the Wehrmacht to Stalingrad requires, in the first place, a basic sketch of the region’s geography. The central objective in 1942 was for the Wehrmacht to reach the Soviet Union’s oil fields in the Caucasus. This provided both the only viable way to remedy Germany’s own critical fuel shortages, but also starve the Red Army of the same.

In 1938 (the last year before war), fully 91% of the Soviet Union’s oil production came from the Caucasus region, in particular productive fields around Maykop and Baku. Even after accounting for some growth in production in other regions of the USSR, the Germans hoped to leave the Soviets with critical fuel shortfalls if they could be successfully cut off from production in the Caucasus. The capture of the Donbas region also promised to leave the Soviets cut off from 80% of their prewar coal output, 95% of their manganese, and 96% of their coke (used in steel production). The oil of the Caucasus had long been a favored objective for Hitler, and there was now no possibility of delaying any longer. “Only through possession of that territory”, he remarked, “will the German war empire be viable in the long term.”

In short, while the USSR was clearly possessed of enormous mineral and industrial resources, it seemed that the Wehrmacht could cut its access to a few critical bottleneck materials and potentially cripple the Soviet capacity to wage an industrialized, mechanized war. Then the Panzer force could slake its thirst on the sweet oil of the Caucasus, and it would be the T-34s that ran dry. “The operations of 1942 must get us to the oil,” admitted Keitel, head of the armed forces high command. “Unless we achieve that, we shall not be able to conduct any operations next year.”

The imperative to reach the Caucasus and the oil fields created a unique operational conundrum. The most productive oil fields, at Baku, were more than 1,000 km away from the German front lines, and reaching them would require a tremendous effort, pushing across the south Russian steppe and then taking a right hand turn towards the south. This would leave the German forces in the Caucasus greatly exposed, and suspended far out in space. Yet, there was no choice. Hitler even said “‘If I do not get the oil of Maykop and Groznyy, then I must end this war.” Of course, he did not follow through, but in real time there was at least some cognizance that this was a do or die moment.

This, in particular, is where the geography of the region plays a crucial role in operational design. The Caucasus region is bounded to the north by a pair of mighty rivers - the Don and the Volga - which bend towards each other in their lower courses. At the narrowest place, these rivers are barely thirty miles apart. This creates a nearly continuous river barrier to the north of the Caucasus.

The conception of the German operations in 1942, therefore, was to take advantage of this river structure to create a solid defensive line - a shield, if you will - north of the Caucasus, to protect the connection to the oil fields. This would entail, in essence, an operation to clear the inside bend of the Don and the lower Volga of enemy forces, so that the German front could be anchored along these two rivers. If such an operation succeeded, the Red Army could only retake the Caucasus by either attacking across one of the two rivers, or by trying to punch through the narrow gap between them. In either case, the Wehrmacht’s strategic defense would be much easier, and in the long run (so it was envisioned) the Soviet Union would be doomed by lack of oil, coal, and manganese.

In the most grandiose German pipe dreams, the success of this operation would coincide with victory in North Africa and the capture of the Suez Canal - successes that would finally convince Turkey and Spain to align with Germany. In this scenario, the Mediterranean and Black Seas would become Axis lakes, and Germany would transition to a grand strategic defense astride a continental empire fed by the captured resources of the prostrate Soviet Union.

A neat plan. If it worked.

The difficulty, as always, lay in attempting to translate ideas from planning maps to reality - and in reality, the Wehrmacht and the eastern land forces in particular were in a parlous state. By the spring of 1942, the army had lost a whopping 3,319 tanks in the Soviet Union and recieved only 732 replacements, for a shortfall of 2,097 vehicles. Motor transport was in similarly dire shape, with a shortfall of over 35,000 trucks. Total casualties by this point had crossed the million man threshold.

This was, very plainly, not an army that was in an adequate state to be aiming for objectives a thousand kilometers away. Field Marshal Fedor von Bock (reassigned to command Army Group South, which would be tasked with the crucial Caucasus operation) had a most sober assessment. In February, he reported:

The repair services were created for a certain intake of repairs. They cannot cope with the accumulated mountain of work produced by the campaign in Russia. . . . General overhauls cannot be performed at all. . . . Lack of spare parts, lack of skilled men, and lack of machinery are therefore at such a disproportion to the number of motor vehicles in need of repair, and above all of general overhaul, that the army, despite full use of all capacities, cannot help itself by the means within its power…

As a result of this situation the picture is as follows. The armored divisions with their 9–15 battle-worthy tanks do not at present deserve that name. The motorized artillery can move into new position only in staggered phases. It is therefore operational only in positional warfare. The bridge-building columns are, with one exception, immobile. Supply services are adequate only because the railway operates well forward. Matters are similar in all areas dependent on motor vehicles.

The army, in consequence, is not combat-ready for a war of movement. It cannot make itself combat-ready by the means within its power.

At the end of March, an assessment of unit battle-readiness concluded that only eight divisions in the entire eastern army were rated “Fit for all tasks” - a proxy for being at full capability. The majority were rated either “Fit for limited offensive tasks” or “Fit for defense.” By comparison, Operation Barbarossa had been launched in June of the previous year with 136 “fit for all tasks” divisions.

In order to prepare the army to launch an operation toward the Caucasus, several measures had to be taken, therefore.

First and foremost, it was quickly determined that the Caucasus operation would be the only major offensive operation undertaken that year in the east. Army Group South would bear this burden, while North and Center remained in a defensive stance. This, in and of itself, was a tacit admission that German strength was horribly degraded. In 1941 they had been capable of launching a major offensive with three different army groups, each on its own independent axis. Now, only one such axis could be pursued, so that resources could be concentrated. This did allow the vast bulk of replacement vehicles, tanks, material, and rehabilitated units to be dedicated to Army Group South, though it was far from clear whether this would be enough.

The second remedial measure was the decision to construct the Caucasus operation in distinct stages. Army Group South would aim to clear the lower Don and Volga basins of enemy troops and then punch into the Caucasus in a sequence of pre-planned phases. This was in acknowledgement of the fact that neither German fighting power nor logistics would allow the army to wage a continuous operation at depth; instead, they would have to expect a stop-start tempo.

The third and final measure, and by far the most sensitive, was to further mobilize Germany’s allies. Troops from Italy, Hungary, Romania, Finland, and other minor German satellites had been participating in the eastern war from the beginning, but now - in light of Germany’s inability to replace manpower losses in time - it was clear that their manpower contributions would have to be increased.

Hitler laid the groundwork by writing personal letters to Mussolini in Italy, Horthy in Hungary, and Antonescu in Romania, laying out the idea that the Soviet Union was on its last legs and a final victory over Bolshevism could be won with an intensified effort in 1942. Mention of the strategic objective - and in particular, mention of Germany’s own degraded combat strength - was strictly forbidden. Through a concerted campaign of cajoling, flattering, lying, and over-promising, Hitler managed to get commitments from these three key allies to raise their force deployments in the east. Whatever later stereotypes exist about the lackluster contributions of Germany’s allies, in 1942 the Nazi Empire’s operational ambitions were explicitly predicated on their contributions to flesh out Army Group South.

Thus, Fall Blau, or Case Blue was born.

The explicit objective of Case Blue was in itself relatively straightforward and prudent. Its goal was neither to capture the Caucasus nor Stalingrad, but to destroy the Soviet armies south of the Don River and the lower Volga; in essence clearing these regions in preparation for a drive south into the Caucasus. In theory, this would give Germany a highly defensible position with the Don and Volga shielding almost the entirety of its front in the south, allowing the Wehrmacht to consolidate control over the Caucasus.

The general sketch of Case Blue was fairly straightforward conceptually, though it had enough turns and maneuvers to make it a tricky job. Army Group South would clear the southern river basins by working its way from north to south in a series of pincer movements, which (it was anticipated) would allow it to scoop up large Soviet forces in encirclements. The first phase would feature three German armies (2nd, 6th, and 4th Panzer Group) driving a short distance to the Don and converging at the city of Voronezh. They would then wheel south and push into the lower Don Bend, converging again around the town of Millerovo and linking up with 1st Panzer Group, before loading up for a final push westward towards the Volga. They would be trailed by a variety of Italian, Hungarian, and Romanian armies which would provide much of the mop up infantry and protect the flanks of the spearhead German units.

If this plan worked as intended, the Wehrmacht would catch several Soviet armies in pockets - recreating the success that they had repeatedly enjoyed in 1941, and had only recently replicated in the annihilation battle at Kharkov. This would leave Soviet forces in the south crippled and essentially establish a solid defensive line protecting the (so far unplanned) attack on the oil fields.

What of Stalingrad? It was noted in the orders for Case Blue, but it received no more attention than other cities like Rostov, Kalach, or Voronezh. Certainly, nobody reading the orders would think this was a particularly important location. The orders noted that it would have to be “reached” and could be used as a “blocking position”, and there was a note in particular that the “Stalingrad area” would be the place where the pincers would meet up as they drove for the Volga. The planning documents, however, were fairly vague as to what would be done with the city - whether it would be masked or screened, captured, or simply bombarded. This is because the implicit assumption of Case Blue was that the greater part of the Soviet forces in the region could be encircled and destroyed to the west of Stalingrad proper.

Certainly, there was no hint that Stalingrad was the focal point of the operation or some sort of deranged Hitlerian fixation, and there is absolutely nothing to support the ludicrous idea that Hitler was willing to fritter away his war in an attempt to humiliate Stalin by capturing the city named for him. Hitler’s only comment on this matter was indifferent: “I wanted to reach the Volga, to be precise at a particular spot… By chance, it bore the name of Stalin himself.”

Luftstoss

Spring came and went, and the Wehrmacht did not appear to be getting any closer to starting Blue. High command wavered over the start date; there simply was not as much fuel or as many tanks and trucks as they would have liked. What ended up forcing the issue, remarkably, was yet another wayward staff plane. Many are no doubt familiar with the 1940 incident in which a plane carrying operational documents accidentally landed in Belgium, forcing a total redesign of the campaign against France. In this case, on June 19th, a small plane flew off course and landed behind Soviet lines. The airplane was carrying Major Joachim Reichel, the chief staff officer for 23rd Panzer Division, and Major Reichel was carrying the complete orders and situation maps for Blue.

Rather than force a return to the drawing board, the news that the operational plan had been lost wholesale prompted the Wehrmacht to begin the attack as soon as possible (aiming, essentially, to get started before the Soviets could digest and act on the information), and a start date of June 28th was issued. The Germans need not have worried - Stalin decided that the captured plans were a disinformation ploy designed to distract from an attack on Moscow, and took no measures to counter Blue.

Blue began with all the hallmarks of a spectacular German victory in the making. The lead elements of 4th Panzer Group tore through Soviet defenses with almost no resistance and began to barrel towards the city of Voronezh. By the end of Day 2 (June 29th), the Germans had overrun the headquarters of Soviet 40th Army, forcing the staff to flee and leaving the men of the 40th without command and control, and thus fish in a barrel. By July 4th, one week into the operation, 4th Panzer Group had reached the Don, and it seemed that another great encirclement was due to be bagged.

It was at this moment that a bizarre cocktail of contingencies began to rip way the Wehrmacht’s great victory. Some of the ingredients are familiar, like fuel shortages and Hitler. By far the strangest, however, was a seemingly incoherent pattern of Soviet counterattacks and disintegration. Let us elaborate.

By the end of the first week, the spearhead German elements at the far north of the line were approaching Voronezh, facing little to no meaningful resistance. Further south, German Sixth Army more or less walked through the Red Army’s defenses. This was entirely unexpected. The Soviets had been digging in here for months - even with tactical surprise, the Germans expected a real fight to breach these lines before they could start driving into the rear. Instead, it seemed as if broad swathes of the Soviet front were simply vanishing.

What exactly was happening? Was the Red army executing a pre-planned withdrawal, to prepare for a later counterattack? Was this a sign of a widespread loss of command and control? Was it possible, as Hitler mused, that “The Russian is finished?”

What seems to have happened was a mixture of pre-planned withdrawal and general panic at the lower levels. There was some intention of waging an elastic defense, but it seems that in many cases these withdrawals lost their cohesion and metastasized into general flight and panic. The loss of a cohesive defense across the Don basin prompted Stalin to issue his famous Order #227: “Ni shagu nazad!” – Not one step back! Nevertheless, the Red Army would keep stepping - and indeed running back for many weeks.

This was all wrong. The operational design of Blue was predicated on large Soviet forces standing in a front loaded defense, so that they could be encircled and destroyed, but this could not be achieved if the enemy melted away on contact. The Germans had a word for this - a Luftstoss. Literally a gust of wind, in the military parlance a Luftstoss meant a strike into the air - a mighty punch that hit nothing. Field Marshall Bock would glumly observe that, “Army High Command… would like to encircle an enemy who is no longer there.”

While portions of the Red Army were melting away and retreating to the east - a completely unforeseen contingency - in other sectors, the Soviets were counterattacking with tank forces. This was equally unforeseen and perhaps even more problematic, in that it created a sense of operational paralysis - a rare occurrence for the Wehrmacht. The plan called for 4th Panzer Group to get to Voronezh and then drive south as fast as possible, but a series of armored counterattacks by the Red Army to the north of Voronezh gave Bock doubts about pulling the Panzers away immediately. This led to a direct confrontation with Hitler, in which both men had valid points. Bock was rightly concerned with sending 4th Panzer south and leaving his northern flank weakly defended, and Hitler was rightly concerned that any delay in getting the Panzers moving could blow up the entire operation.

What this reflects, above all, is that this German force had insufficient mechanized forces and fuel to wage an operation like this. This was an operation being fought on a shoestring budget, so to speak, which left no margin for error. Any wasted time or wasted force could lead to a catastrophe, and this complete lack of cushion made operational uncertainty threatening in the extreme.

And so, facing an enemy who would not cooperate by standing still between the great German pincers, Case Blue broke down into an operational calamity, with the key German maneuver units being sent back and forth across the Don Basin, trying to catch something, and frequently being stopped for days at a time awaiting fuel deliveries. III Panzer Corps, for example, would cross the Donets River twice and drive over 250 miles in July looking in vain for somebody to fight - wasting precious time and fuel on what amounted to a driving tour southwestern Russia.

In the end, Blue wasted much of the summer and tremendous amounts of fuel searching in vain for a decisive battle to the west of the Don River, when the bulk of the Soviet forces were either on the east side or hightailing it that direction as fast as they could. German commanders across the theater reported the same repeated experience - rather than encircling large Soviet units, the best they could do was to (by accident) run into retreating Soviet columns.

The map of Army Group South’s movements paints a sufficient picture of the operation’s futility - various units crossing back and forth, ramming into each other, closing pincers with nothing in between them, vainly attempting to trap an enemy that was no longer cooperating.

Could it have been different? It is of course popular to conduct thorough autopsies, and to blame particular decisions - especially if they were made by Hitler. Personalities matter, and decisions matter (Hitler certainly thought so when he fired Bock at the end of July), but that was not quite the problem with Blue. The flight of huge sectors of the Soviet front certainly threw a major wrench in the works, but even this was not really the problem.

The problem was one of force generation. The Wehrmacht simply had too few trucks and tanks, and too little gasoline to fight this operation - this meant that a small handful of keystone units, especially the overstretched Panzer forces, had to shoulder all the operational burdens.

Take, for example, the heated argument between Hitler and Bock as to whether 4th Panzer ought to run to the south immediately or loiter to stabilize the northern flank. It is easy to get bogged down comparing the two options, but it is rather more interesting to note that the nature of the debate itself shows forth the Wehrmacht’s doom. The Fuhrer and the Field Marshal were, in essence, arguing about whether a Panzer Army ought to be on the north or south end of the line. A single Panzer Army cannot be in two places at once. It would be much better to simply have another Panzer Army - but the Germans did not.

The fact that Case Blue depended - even in its best case scenario as drawn up on paper - on a handful of mechanized units screaming back and forth across the theater reflects the fact that the Wehrmacht was simply understrength and could only hope for success by massively overburdening these forces.

Perhaps the best example is that of XXXX Corps. This Corps began the operation with a total of just 230 tanks, and yet it was tasked with subdividing itself and pursuing three different objectives in all manner of opposing directions. Asking an understrength corps to be in three places at once is not a recipe for success. The Corps’ chief of staff put it rather blandly: “the corps was aiming at goals in three directions at once, and was running the risk of not reaching any of them.” At this point, command might have argued about which objectives to pursue and which to ignore, but the entire conversation would have been pointless - XXXX Motorized Corps ran out of gas and had to sit still for several days.

Ultimately, Blue attempted to do too much with too little, and no matter what the minutia of the decisions were, the meager mechanized forces simply could not adequately handle all of these operational tasks. The Red Army’s decision (whether intentional or not) to retreat out of the forming pockets did not help, but the bigger issue was that there were inadequate forces to weave a sufficiently thick net around the Soviet forces. Or, as the great historian Robert Citino put it, there really was nothing wrong with Blue “that a thousand or so extra tanks would not have fixed.”

The Decision for Stalingrad

Blue had put the Wehrmacht in an awkward position. From a territorial perspective, the operation had been a sort of success, in that it brought Army Group South over the Don River to the doorstep of the Caucasus. While it would not have been fair to say that the path to the oil fields was wide open, the Wehrmacht was at the very least within striking distance, poised to make one final lunge for the oil.

And yet, it was all wrong. There had been no battle of annihilation, no great encirclements, and no destruction of Soviet combat power on a meaningful scale. Instead, the Red Army forces inside the Don bend had largely melted way to reconstitute themselves on the other side of the river. Thus, although the Caucasus and the oil was now seemingly within sight to the south, Army Group South faced a whole slew of intact Soviet armies hanging over the top of its head to the north.

The basic question, then, was how the campaign could be continued towards the oil fields without this enormous Soviet force coming down from above.

Case Blue had originally stipulated that an advance on the Caucasus could only be attempted once two conditions had been met. First, the mass of the Soviet forces in the lower Don and Volga needed to be crushed (or at least badly mauled), and secondly the Wehrmacht needed to hold a blocking position on the Volga which could shield the lines to the Caucasus. Neither of these objectives had been achieved in the summer campaign, but on July 23rd Hitler issued a new directive greenlighting the next phase of operations. This direction (Fuhrer Directive 45, to be specific) has been hotly debated ever since, and identified as one of those many potential points where Hitler can be said to have lost the war.

The essence of Directive 45 was to split Army Group South into two sub formations, pursuing both the next stage goals in the Caucasus and completing the original goals of Case Blue simultaniously.

Army Group A would commence the invasion of the Caucasus - codenamed “Operational Edelweiss”. Group A’s to-do list was formidable. It needed to envelop the Soviet Caucasus armies in a great pincer move (and destroy them before they could withdraw into the mountains), capture several Black Sea ports, and motor through the mountains to capture three major oil fields, at Mayakop, Grozny, and Baku. It is easy, sometimes, to think of the Caucasus as a sort of footnote or mop-op operation, but the scale of Edelweiss was absolutely enormous. It has been pointed out that the distance from Rostov (the operation’s starting point) to Baku was roughly as large as the distance from Rostov to Warsaw, meaning that even after all the fighting they had done over the previous year, the Wehrmacht was barely halfway to the end. The Caucasus region was colossal (larger than either prewar Poland or France), and many of the cities slated for capture were huge. Thus, far from being some sort of reasonable wrap-up job, Edelweiss promised to be an enormous operation in its own right.

Accordingly, Group A was to be the main effort and was given strong forces (such as were available). Under the command of Field Marshal Wilhelm List, Group A was to consist of five armies - the 17th, the Romanian 3rd, and the two Panzer Armies (1st and 4th), to be joined by the 11th Army under Erich von Manstein, which was to be ferried over from Crimea.

This left precious little for Group B, which in the end consisted of little more than the German 6th Army under General Paulus, with a few Hungarian and Italian forces in tow (though Hitler would eventually reassign Panzer Army 4 to from A to B). Group B’s task was to easier said than done. The actual wording of Hitler’s directive instructed it to move towards Stalingrad, “smash the enemy forces concentrated there, occupy the town, and block the land-bridge between the Don and the Volga, as well as the Don itself.” In other words, Sixth Army was to establish the blocking position that Case Blue had aimed for, and use Stalingrad as the anchoring point of this new defensive line that would protect the long lines of supply to the Caucasus. As Sixth Army advanced towards Stalingrad, the Hungarian and Italian armies would lag behind and protect the flank.

Perhaps the best way to think about the construction of these operations is to consider what Germany’s best case scenario was. What, precisely, did Hitler and his staff hope for out of these decisions? In the most rosy outcome, Group A would have completely captured the oil fields in the Caucasus, and work could have begun creating viable overland links both to supply operations there and to extract oil. This strung out position in the Caucasus could then have been defended by a strong defensive position on the south side of the Don and Volga Rivers, with the 6th Army (a powerful and oversized formation) guarding the gap between the rivers, using Stalingrad as its defensive anchor.

All in all, this would have been a fairly strong position. The aims of Blue and of its follow-up operations were sensible. The Germans simply had inadequate forces to achieve them, and once again the Soviets refused to play ball.

Sixth Army dutifully jumped off its start lines and started to drive east. In the path lay the Soviet 62nd and 64th Armies - perhaps another opportunity beckoned to win an encirclement battle? Once again, however, lack of motorized forces and especially a lack of fuel prevented such an outcome. In fact, by the closing days of July, Sixth Army was almost entirely immobilized by lack of fuel, and would not be able to get moving again until August 7. By this point, nobody could deny that Paulus’s force was simply inadequate for its assignments, and Panzer Army 4 under General Hoth was reassigned to Army Group B to assist it.

The notion of an entire powerful Panzer Army sweeping northward to join the battle is the stuff of German fever dreams - but by this point, it was only a dream. In order to get Paulus’s force moving again, 6th Army had to be promoted to top priority for fuel. This bumped the other units down, and so Hoth’s Panzer Army was now the lowest priority, severely limiting its mobility. Rather than rushing up to join the action in heroic fashion, it made a plodding rumble across the steppe as fuel supplies allowed. It is very difficult for an army to wage a campaign of maneuver when it is unable to fuel all of its major maneuver elements at the same time.

On September 2nd, the two major German formations - 6th Army and Panzer Army 4 - linked up on the approach to Stalingrad. Again, two massive German pincers had slammed shut, but again they had moved too slowly and nothing of note was caught between them. A final attempt to encircle the Soviet armies on the open plains outside Stalingrad had failed, and the Wehrmacht found that its prey had withdrawn into the city. 6th Army had dealt out a good blow while forcing its way across the Don - taking some 57,000 prisoners and destroying a sizeable Soviet tank force - but this fell far short of the enormous encirclements of the previous year, and the Wehrmacht had so far failed to destroy any of the Red Army’s operational level units.

We come at last to the fateful decision, and the core question. How did the German campaign - and indeed, the war - come to hinge on the previously insignificant city of Stalingrad?

General Kleist (commander of 1st Panzer Group) had concluded that “The capture of Stalingrad was subsidiary to the main aim. It was only of importance as a convenient place, in the bottleneck between the Don and the Volga, where we could block an attack on our flank by Russian forces coming from the east.” And yet, already by July 30th, Alfred Jodl (Wehrmacht Chief of Staff) had concluded that “the fate of the Caucasus will be decided at Stalingrad.” How could this be so?

The Wehrmacht had arrived on the doorstep of the city without succeeding in inflicting a major defeat on the Red Army. They therefore faced the looming threat of intact and growing Red Army forces in the theater, indeed, the Stavka was already preparing reserve armies for the newly formed Soviet Stalingrad Front. So what to do?

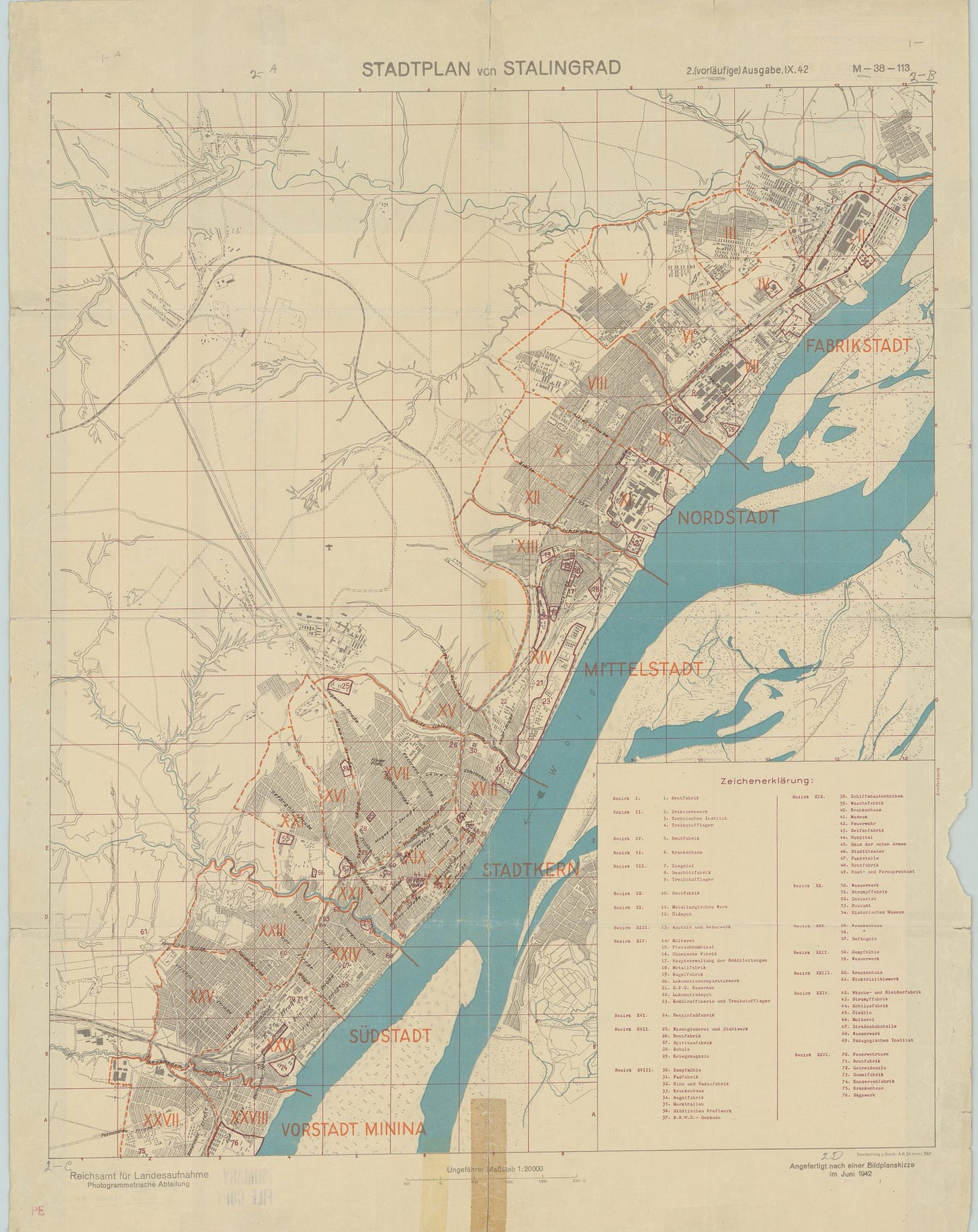

Stalingrad itself was rather unusual. It was not shaped like a normal city, but more like a rectangular strip full of heavily built up industrial areas. Since the city was on the western bank of the Volga, it formed a ready-made heavily fortified bridgehead for the Red Army. Because it could be both supplied across the river and defended by powerful Soviet artillery forces on the east bank, it was impossible for the Wehrmacht to surround it or besiege it.

There were, really, only a few options. The Wehrmacht could sit where it was, exposed on the steppe at the end of a long and tenuous supply chain and wait for the Red Army to counterattack. It could retreat and abandon the campaign in the Caucasus, but this would mean giving up on the oil and thus any prospect of victory. Or, it could go into the city, try to dig out the Red Army defenders, and establish a defensible position for the winter.

Faced with a set of choices that ranged from bad to catastrophic, the Germans chose the option that was merely bad. On September 5th, the assault on Stalingrad was launched. The Luftwaffe swarmed overhead, and the 6th Army went into the city.

Rattenkrieg

Since our focus in this series has been operational maneuver, the fight for Stalingrad itself does not fit in very well, since maneuver and operational level warfare ceased to exist as such. Far more interesting for our purposes are the broad decisions that led to Stalingrad and to the resolution of the campaign. Nevertheless, we may indulge in a few words about the fight in the city itself.

Stalingrad, more than any other battle in the Nazi-Soviet War, presents a visceral image of an apocalypse on earth. Artillery and aerial bombardment quickly reduced much of the city to rubble, limiting the use of tanks - correspondingly, most of the 4th Panzer Army was sent back to the Caucasus, and it was 6th Army’s infantry divisions that would have to shoulder the burden of Stalingrad. This was a battle of individuals fighting in extremely close quarters – especially given the Soviet practice of “hugging” the Germans, which meant taking up positions so close that the Germans could not call in artillery strikes for fear of hitting themselves. Veteran German soldiers who had fought from Poland, to France, and now to the seeming ends of the earth in Russia found that the scope of their war had shrunk down to close quarters, or even hand to hand combat for the control of ruined buildings.

This was a battle fought in mounds of rubble, basements, streets, and sewers, waged by infantry wielding small arms, machine guns, and mortars. In many cases, the distance between the two sides amounted to a single city street, or even a single interior wall in a half-destroyed building. The scale of the war was radically altered; instead of targeting objectives spread out hundreds of miles apart in the vast Soviet interior, the Germans now fought to capture individual blocks, factories, apartments, and even drains and sewer culverts. This latter charming feature led the Germans to dub the battle a “Rattenkrieg” - rat war. The key objectives were very specific city sites - most famously the Dzerzhinsky Tractor Works, but also various railway stations, docks, parks, apartment blocks, and factories. Perhaps the most important site was Mamayev Kurgan, or Hill 102 to the Germans. An enormous grassy hill which had once been a burial ground, Hill 102 offered dominating ground over the city center and the docks. There was, perhaps, something primordial and atavistic about a ferocious battle for an ancient battle ground. As Macaulay put it:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his Gods.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.