Who is the greatest general in history?

The question, while fun to contemplate, is indeed a thorny one, as it presumes that the figure of the “general” takes a consistent form that can be compared fairly across the ages. Upon reflection, this is not immediately obvious. One can hardly imagine Konstantin Rokossovskiĭ or Erich Manstein personally leading the charge of the Macedonian cavalry the way Alexander the Great did - but it is equally difficult to imagine Alexander sitting dutifully in a command post, pouring over situation maps and directing the movements of dozens of divisions from afar. The commander traded his lance and sword for maps, pencils, and telephones.

To be sure, the role of the general has changed throughout the ages, from the heroic battlefield commanders of the ancient world who fought and killed in the melee with their men, to ever more cerebral and technical maestros of the map. Generals still face danger and may be killed by deep striking weapons like artillery, missiles, and aircraft, but the days have long since come and gone where a general might be expected to intentionally engage in combat.

Despite these radical shifts, certain qualities of the successful military leader remain eternal and transcendent: decisiveness, steady nerves, properly balanced aggression and prudence, and leadership.

This last quality has become something of a trite and cartoonish concept for many people today. “Leadership” has been stripped down into a quality that many people genuinely believe can be taught in a classroom or acquired from reading droll business books, or (God forbid) watching motivational YouTube videos with manipulative soundtracks. It is a transcendent quality that many are eager to strip of its transcendence so that it can be bureaucratized, systematized, and monetized.

This is nonsense. Leadership, genius, decisiveness, these are qualities that emerge organically from the process of collective struggle and effort. The first kings and chieftains were the men who killed the wolves and tigers terrorizing the camp, not the graduates of pedantic leadership academies. Genghis Khan was acclaimed the ruler of all the steppe tribes because he killed his enemies and rewarded his friends, not because he read the latest Simon Sinek book. And above all, the Duke of Wellington said that Napoleon’s presence at a battle was worth 40,000 men because the latter innately possessed the indefinable and irresistible quality of genius, not because of his Enneagram type. One must not confuse leadership with power or greatness with titles.

The duties of the general have changed throughout history, but the archetype remains timeless, if indefinable. The great fighting man, in any age, is something that we recognize when we see it, and few better fulfill the archetype than Napoleon.

Napoleon, by any counting, commanded more major set piece battles than any other man in history, and he almost always won. At the peak of his powers, between his Italian campaign of 1796 and the beginning of his downfall in Saxony in 1813, he fought 53 major battles and suffered defeat in only 4 of them. He won victories repeatedly when fighting at a numerical disadvantage, and he won in summer and winter, deserts and mountains, from France to Egypt to Russia.

Napoleon did, of course, lose his wars in the end, but it must be recognized and acknowledged that this was a man so prodigiously skilled at warfare, commanding such a finely machined army, that his defeat required the cooperative work, without exaggeration, of essentially all of Europe. The so-called War of the Sixth Coalition, which finally brought about his defeat, pitted Napoleonic France against Russia, the United Kingdom, Prussia, Austria, Portugal, Denmark, Sweden, Spain, and eventually almost all of the Germanic principalities. A formidable alliance - but Napoleon still somehow made it close.

So who is the greatest general? We can defer to Napoleon’s great British nemesis, the Duke of Wellington. He was asked the same question once, and answered without hesitation: “In this age, in past ages, in any age, Napoleon.”

Let us dwell with Napoleon and learn his art of war.

How to Move an Army

Napoleon practiced a discernable system of warfare, with motifs, techniques, and principles that are clearly identifiable. However, this system or art of war must be teased out of Napoleon’s battles, because he himself never wrote out any sort of systematic methodology of warfighting. His military acumen was intensely practical, and the Napoleonic system was created from doing, rather than from institutional study and methodology. This stands, for example, in sharp contrast to the Prusso-German way of war in the 19th century, which was created through an intentional program of reform and theorizing by their General Staff. Napoleon had no time for this - he simply fought battles. To the extent that he left meaningful quotes about war making, they take the form of aphorisms, rather than a single systematic treatment of war.

Two overarching principles are clearly visible in the Napoleonic system, and in Napoleon’s own words. These are, namely, the absolute priority of offensive action, and the criticality of movement that is both rapid and ambiguous. Napoleon was adamant that the central aim of warfare was the destruction of the enemy’s fighting mass, and that all other concerns were subordinate to the need to find and destroy the enemy’s main field army. In 1797, he explained it thusly:

“There are in Europe many good generals, but they see too many things at once. I see only one thing, namely the enemy’s main body. I try to crush it, confident that secondary matters will then settle themselves.”

Napoleon eschewed the dance between diplomacy, position, and battle, and instead gave primacy to battle, preferring to negotiate only after the enemy’s main fighting force had been vaporized. He also strongly shied away from siege warfare, preferring to seek decision through the direct clash of the main field armies. Insofar as he moved towards enemy supply depots and cities, he did so because threatening them would force the enemy to offer up their field army for battle. It was all well and good to drive towards the enemy’s capitol, but this was because doing so would force them to put their army in the way, allowing it to be attacked and destroyed.

With this goal in mind, Napoleon was manically focused on the offensive. He believed fundamentally that decisive offensive action was crucial in that it allowed him to dictate the tempo of operations and force the enemy to become a reactive entity, granting him full initiative. “Make war offensively;”, he said, “it is the sole means to become a great captain and to fathom the secrets of the art.”

Napoleon executed his attacking style of war with an army that was able to move both quickly and efficiently while disguising its movements. As he himself famously said, “Strategy is the art of making use of time and space. I am less chary of the latter than the former; space we can recover, time never.” The Grande Armee could move at shocking speed for the era, but it did so in a dispersed and concealed manner that left enemies at great pains to guess where it was going. This combination of speed and deception repeatedly left Napoleon’s opponents disoriented and wrongfooted before a musket was ever fired.

Three particular ingredients were crucial for granting Napoleon’s army its characteristic speed.

The Corps System: The organization of Napoleon’s army into self-sufficient combined arms corps allowed the army to disperse and travel on independent lines of advance. This made the army both faster, by distributing it on many different roads, and more ambiguous by disguising its intentions.

The Officers: By dispersing his corps, Napoleon also by definition dispersed his command system. Unlike Frederick or Hannibal, he could not personally travel with and command the mass of his army, because there was no single mass. Therefore, the precise movement of the army required Napoleon to delegate to competent officers who could be entrusted with the independent command of a significant force. This was a monumental step towards a recognizably modern command and control system and professional officer corps. At the apex of this system were Napoleon’s famed Marshals.

The roads and towns of Europe: The Grande Armee was able to move at great speed thanks to the density of the roads and settlements throughout Europe. The road system allowed for not only the rapid travel of the main bodies of men, but also communication between the dispersed units via messengers on horseback. Furthermore, the population density allowed the army to move without supply chains by requisitioning food from local civilians as they passed through.

Napoleon’s armies could move very fast indeed, but the pace of this advance would vary widely depending on the phase of the operation. At the outset, the army was widely dispersed and marched at a (relatively) leisurely pace. Most of the time, Napoleon’s forces moved at between 10 and 12 miles per day. During this opening phase, the army would also be maximally dispersed, with some of the opening fronts being quite colossal. In 1796, Napoleon’s invasion of northern Italy began with his forces spread out across a 75 mile front; the 1805 Ulm campaign began on a 125 mile front, and the famous invasion of Russia began with the Grande Armee arrayed across a 250 mile front.

Dispersing the army across a wide starting line allowed Napoleon to capitalize on an important asymmetry: his army could move faster and more precisely than the enemy. Therefore, by stretching out the theater of operations, he created an advantage for himself, because the faster party will always have the edge in a wider arena. The dispersion of the army both disguised his intentions from the enemy and created maximum flexibility for the French by allowing them to maneuver towards wherever the enemy decided to concentrate his forces. In some cases, the wideness of the front compelled the enemy to split up his own forces, in which case Napoleon could destroy the enemy army in pieces.

As the Grand Armee advanced on the enemy, it was obscured behind a dense screen of cavalry. The cavalry screen had both intelligence and counterintelligence functions. Riding ahead of the mass of the army, the cavalry would scout and scour for intelligence about the enemy’s position and movements, but they were also tasked with detecting and chasing away the enemy’s own cavalry scouts. With the movement of the army obscured behind this moving screen, the enemy could never get more than a vague sense of Napoleon’s forces and intentions. The screen formed a curtain, behind which the French mass was shrouded in fog. In most cases, the cavalry screen was the only portion of the French army that enemy scouts would actually be able to physically see.

In general, as the French got closer to the enemy force, the front narrowed as the corps gradually drew closer together, preparing to concentrate for the decisive battle. The movement of the army was less like a monolithic column and more like a net that was slowly drawn close as they moved nearer to the enemy. Then there came a critical moment, when Napoleon would pull the proverbial trigger. At that point, the corps would begin to rapidly snap together into position for battle. The pace of the march would radically increase as the army drew together. In one of the most famous and celebrated examples, Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout marched Third Corps nearly 80 miles in about 48 hours to reach the battlefield.

This, then was the idealized form of maneuver in Napoleon’s system of warfighting. A divided army comprised of self sufficient corps marching across a widely dispersed front, with a cavalry screen obscuring its precise movements from the enemy. This left enemy commanders disoriented and in the dark, as they perceived only vaguely the French fighting mass snaking its way forward like a many headed hydra. Only once the enemy army had been decisively located would the dispersed army suddenly snap together on the enemy, forcing him into decisive battle.

Napoleonic Combat

Napoleonic battle was a fluid interplay between the three arms: infantry, cavalry, and cannon. Notwithstanding Napoleon’s many famous quotes about the preeminence of artillery on the battlefield (his fondness for cannon originating in his early career as an artillery officer in the Bourbon army), there was no single arm that was more important than the other. All three arms interacted with the others in unique and important ways, and successful battle required a synergistic application of the whole.

The Cornerstone: Napoleon’s Infantry

The most numerous type of soldier in the armies of both Napoleon and his adversaries was the humble line infantryman, equipped with musket and bayonet. His was a brutal, terrifying existence.

The musket was, in retrospect, a rather curious weapon. Its range and accuracy were extremely limited. In a famous experiment conducted by the Prussian army, a canvas target 100 feet wide and six feet tall was set up for a battalion of line infantry to test fire upon. The size of the target created the generous condition of simulating a volley fired at an entire enemy battalion. The results therefore approximated the odds, not of hitting a single specific enemy soldier, but of hitting anybody in the entire enemy unit. The results were not encouraging. From 150 yards out - well within the advertised range of a musket - only 40% of the test shots hit the canvas at all, while from 75 yards the rate was only 60%.

From even these modest distances, a tremendous amount of shot would be wasted. However, when units closed to point blank range - within fifty yards, or so - casualties could be horrific, as the narrow distance finally mitigated the weapon’s unreliable accuracy, and the sheer volume of a battalion volley threw huge amounts of lead into the air. Units that had to stand at close range and exchange repeated volleys with the enemy could be vaporized. At Austerlitz, one particularly miserable regiment stood in the line exchanging fire until it was completely destroyed, losing 95% of its men. Therefore, on balance, one might say that although an individual musket was not a particularly reliable or accurate weapon, a mass of musketeers fighting in close order was a very powerful and lethal military system.

Within the infantry, there were shades of specialization. Famously, armies fielded units of “Grenadiers.” Originally, the name was a literal description - primitive grenades were heavy and unstable, and so it was common practice to select only the tallest and strongest soldiers for grenadier units, making them the physical elite of the army. By Napoleon’s time, however, dedicated grenade units had fallen out of favor, and so the term grenadier ceased to refer to their weaponry and was instead a status label used for elite infantry, making the various guards grenadiers regiments simply the most prestigious and experienced musketeer units. Thus, in the Grande Armee, a grenadier was equipped identically to any other line musketeer, but he was taller, more experienced, better paid, and had more cachet with women. A typical infantry battalion might have a single company of grenadiers, who would serve as the battalion’s shock troops and lead unit.

A second particular subset of French infantry were the Voltigeurs, or skirmishers. These were men with particular skill as sharpshooters, whose basic task was to screen the deployment of their comrades by harassing the enemy line with musket fire, usually directed at officers.

While Napoleon did tinker with the precise organization of the army over time, an idealized example may illustrate how the infantry deployed to fight, supported by skirmishers. A typical French infantry battalion would be made up of nine infantry companies of 120 men each, typically aligned 40 wide and three deep for line combat. Eight of these companies would be line infantry, and the ninth would be skirmishers. As they marched on the battlefield, the objective was to remain in column (for quick marching) as long as possible, before deploying smoothly into firing lines. Successfully managing the pivot from marching column to firing line was a crucial aspect of battlefield effectiveness.

Upon nearing the contact point, the lead company (the skirmishers) would jog ahead and disperse, kneeling down to harass and screen the enemy with targeted fire. Screened by these skirmishers, the column would begin to fan out, with each company slotting into line as they closed the final distance, before they began the bloody process of exchanging volleys.

Thus, what appeared at a distance to be a narrow column would first give way to a cloud of skirmishers opening fire, behind whom advanced a terrifying line of musketeers, 320 wide and 3 deep, ready to give fire. This would make an unbroken line of men 200 or more yards wide, able to fire up to 1280 rounds per minute (only the front two lines being able to fire, each man firing at a rate of up to two rounds per minute). This would make one battalion, advancing to contact, and when fighting in full force Napoleon could bring upwards of 200 battalions to the field. Little wonder, then, that many battles had front lines that stretched many miles, or that tens of thousands of men could be killed in a single day under such conditions.

The basic art of the Napoleonic infantryman, aside from marching, reloading, and firing his musket in the volley, consisted in shifting between three various types of formation based on battlefield circumstances. These were, respectively, the column, the line, and the square. Each formation offered some particular situational advantage, in the form of either mobility, firepower, or defense, but with potentially offsetting drawbacks.

The column was the formation for marching - not just on the road, but during the approach on the actual field of battle. It offered the fastest and most agile movement, and it also offered the most density and shock value for bayonet charges. In contrast, the line formation was immobile and sluggish, but provided maximum firepower. In the Grande Armee, line infantry regiments usually lined up three ranks deep, with the first two ranks offering fire and the third rank stepping forward to fill holes in the line as men fell - this was a ruthlessly efficient, shallow formation designed to make use of every possible musket. The final base formation, the square, was the doctrinal response to cavalry attack. A square provided 360 degrees of protection, with at least three ranks of men facing in every direction. Typically, the front ranks would kneel with fixed bayonets while the second and third ranks offered musket fire. This created a dense formation bristling with bayonets and gunfire that could ward off cavalry attack, but at the expense of sharply reduced firepower and greater vulnerability to ranged fires, owing to how closely the men were crowded together. In particular, a densely packed square of infantry could be ravaged by cannon fire.

Much of the tactical art of Napoleonic warfare revolved around mediating the transition between these formations - not only properly moving your own infantry into the correct formations, but also attempting to force the enemy into moving into formations that were disadvantageous to him and to disrupt his own synergistic use of arms.

The infantry square provides a potent example of this. During the early phases of battles, it was common for cavalry squadrons to skirmish with each other. If the enemy’s cavalry could be defeated and forced to withdraw, then it became possible to directly threaten the enemy’s infantry with a cavalry attack. This would compel them to form squares. Infantry in a crowded square were well defended from cavalry, but at this point they could be pummeled, either with one’s own infantry (infantry in a line having four times the firepower of the equivalent men in a square), or - even more devastatingly, attacked with horse drawn artillery, which could gallop up and unleash devastating close range barrages on the packed squares of musketeers.

This was a standard battlefield tactic which emphasizes the synergistic, back and forth logic of the era’s combat. Cavalry alone cannot simply crush a battalion of infantry - the infantry will simply form squares and become impenetrable hedgehogs. But cavalry can force the infantry to form these squares so they can be punished with musket or cannon fire. All the arms must work together to create advantage.

Similar synergistic warfare was required for the successful use of stacked charges. Given the horrific casualties that could result from extended exchanges of musket fire, it was common to seek a decisive result by launching a shock action bayonet charge with infantry in columns. This did offer the potential of breaking through the enemy line and shattering his formation, but charging head on into musket fire was a problematic concept. Therefore, column charges needed support by intense artillery bombardment, with cannons brought forward to hammer on the spot where the charge was intended to land. Napoleon, personally, was emphatic that bayonet charges could not succeed without artillery support.

The God of War: Napoleon’s Artillery Arm

Napoleon’s great regard for artillery is well known. In his early military career, he had served as an artillery officer in the Bourbon army, and deeply internalized the importance of cannon. He famously quipped that “God favors the side with the best artillery”.

Artillery in Napoleon’s era had already become an extremely potent weapons system. Two changes, in particular, had enhanced its deadliness. The first was the universal adoption of pre-packed ordnance, which greatly increased the rate of fire by freeing the gunners from having to individually load the propellant charge and cannonball. The second great advance was one of Napoleon’s personal organizational priorities: the move to militarized transportation.

In the 18th century, it had been typical practice for cannons to be hauled to the battlefield by hired civilian drivers and horse teams. Because these civilians were loathe to put themselves in danger (and skittish and unreliable under fire), artillery was generally unhitched in the rear areas and then manually dragged to firing positions. Napoleon ditched the civilian contractor system and adopted militarized transport, with dedicated horse teams and drivers within artillery battalions, including and especially the deadly “horse artillery”. These were light cannon that could be dragged nearly at full gallop into battle along with the gunnery crew, who were also mounted.

A precursor to self-propelled artillery, horse cannon could be brought up to critical points at lightning speed, rapidly unhitch, and provide close fire support. The speed at which these cannon and their crews could rush to the front, deploy, and open fire recalls the pit crews of modern car racing - an impressive display of rehearsed coordination and precision. Horse artillery completely changed the nature of cannon, from clumsy, lumbering systems that sat mostly immobile in their batteries, to responsive, flexible, mobile weapons that could be deployed at specific points in response to specific needs. This greatly enhanced the deadliness of the artillery arm. There was little as terrifying for an infantry battalion as being forced to form a square by attacking cavalry, only to see the horse artillery come galloping up to the front to discharge canister shot right into the square.

Canister shot was a particularly nasty innovation that gave artillery an added level of firepower against closely packed infantry. While traditional round shot was used at longer ranges, against close order infantry it was typical to use canister - more or less a thin walled can filled with iron or lead balls, perhaps an inch across. Upon firing, the flimsy canister disintegrated, blasting the contents out in action that resembled nothing less than a giant shotgun. At close ranges, canister shot could quickly vaporize infantry and created horrific carnage.

Artillery was used in battle from the very first moment. Barrages were laid down to cover the first advance of the infantry onto the field (more likely than not, the first men to die in any given battle would fall to cannon balls crashing in from far beyond musket range), and then continuing to pummel the enemy throughout. Once a position in the enemy line seemed to be weakening, artillery fire would be concentrated on that point to fatally weaken it, so that it could be pierced by a shock action charge. In this way, the action of the batteries on the field resembled the movement of the corps system - dispersed and lower intensity at first, then concentrating and intensifying greatly at the decisive moment.

Shock and Awe: Napoleon’s Cavalry

The final and most cinematic arm of the Napoleonic army was the cavalry. The uses of cavalry were threefold: reconnaissance and screening during the advance to battle, shock and mobility in combat, and exploitation and punishment against a defeated enemy. Or, as Napoleon himself put it, “Cavalry is useful before, during, and after the battle.”

Notwithstanding his eternal love of artillery, Napoleon was equally clearsighted about the absolute necessity of a strong cavalry arm. Most importantly, as he understood it, cavalry was the arm that allowed for decisive victory, because it was the cavalry that would run down and exploit a compromised enemy army. Without a strong cavalry force, a defeated enemy could simply withdraw from the field. While cannon and musket killed the most men during the set piece phase of the battle, it was cavalry that inflicted terrible damage once the defeated army broke and attempted to flee. On this subject, Napoleon wrote:

“I say that it is impossible to fight anything but a defensive war, based on field fortification and natural obstacles, unless one has practically achieved parity with the enemy cavalry; for if you lose a battle, your army will be lost.”

Accordingly, Napoleon and his staff exerted great effort regularizing and organizing the cavalry arm, which had suffered neglect during the revolutionary period. Each of the Grande Armee’s corps had an organic cavalry element, as did Napoleon’s elite Imperial Guard, and the army also retained an independent cavalry reserve for handling special tasks and emergencies. Allowing for some slight variation and special units, French cavalry fell into three broad categories.

Cuirassiers formed the heavy cavalry - in this case, “heavy” being not merely a military designation but also a literal description. Cuirassiers were, to put it succinctly, huge men, riding huge horses, wearing huge armored breastplates (the Cuirass, after which they were named) and swinging long swords. They formed the core shock element of the cavalry, deriving their combat effectiveness from the literal weight and power of their charges. Although generally equipped with a pair of pistols as well, they generally did their damage with their swords, which could cut down exposed infantry like a scythe through grass.

The second cavalry form, the Dragoon, was a general purpose problem solving soldier. More lightly armored than the heavy Cuirassiers, the Dragoons were instead more versatilely equipped, carrying not only a sword and pistol, but also a shortened musket. Trained for both mounted and dismounted combat, they had suitability for nearly limitless different tasks, and could operate in cavalry screens, protect the army’s flanks, go on raids or other special missions, or - in a pinch, dash to vulnerable positions and dismount to bolster infantry forces.

The final arm (and the most numerous) were the Light Cavalry, including the famous Hussars. The Light Cavalry instantiated the swagger, braggadocio, and daring of the archetypical cavalryman. Armed with pistols, carbines, and sabers, their tasks were screening, scouting, harassing, and - especially - exploitation. During the advance to battle, they were expected to be the lead elements, harassing the enemy and disrupting his deployment, nipping at his flanks and points of exposure, and screening the French deployment. In the (frequent) case of victory, it was the light cavalry that pursued the fleeing enemy, running down retreating infantry, capturing baggage and artillery trains, and generally doing everything possible to turn a tactical victory into a total rout.

Well did Napoleon say, “Without cavalry, battles are without result.”

All in all, the French army under Napoleon was a versatile and well drilled machine capable of astonishing battlefield dexterity. Time and time again, it demonstrated methods for seamlessly integrating cavalry, artillery, and infantry operations in response to shifting battlefield conditions. At the Battle of Auerstadt (discussed in detail below), one infantry division went through the entire range of tactical arrangements in a single day - approaching the battlefield in column, deploying into lines to deliver volley fire, withdrawing back into squares to beat off an incoming cavalry charge, and then redeploying into columns to deliver a finishing bayonet charge.

No method of warfighting is perfect. Napoleonic warfare always threatened to devolve into horrific attrition battles, and over time the British in particular evolved ways to mitigate French tactics. Yet on the whole, these basic doctrines and methods worked nearly seamlessly, and they brought France well over a decade of continuous battlefield victories.

Blueprint of Strategic Destruction

Given the sheer volume of battles that Napoleon fought over his career, it becomes possible to identify patterns and systems that are quintessentially Napoleonic, despite the fact that he never actually wrote down anything like a system or handbook for warmaking. As a practitioner, rather than an author, we might say that Napoleon’s theory of battle was implicit, rather than explicit. Still, we can with reasonable confidence identify what we might call Napoleon’s idealized approach to battle. This was an idiosyncratic battle scheme which fit Napoleon’s maniacal desire to destroy as much of the enemy’s fighting power as possible in a set piece field battle.

Let us walk through an idealized variant of Napoleonic battle, and then examine a few specific instances where it was implemented most perfectly.

To begin, we should note that the innovative system of corps allowed Napoleon to take battle with relative ease. To begin with, the dispersed and rapid movement of the corps usually left the enemy in a state of confused inactivity, allowing Napoleon to bear down on him and force a battle. The individual corps, however, were also valuable tools for forcing the enemy to take the fight.

Time and time again, upon locating the main enemy mass, Napoleon would bring the entire army to converge on it. The first corps to arrive was tasked with ensuring that the enemy army did not slip away, by attacking it and pinning it in place. Napoleon’s enemies almost always obliged and took the battle, because they saw in front of them not the entire Grande Armee, but a single corps of perhaps 30,000 men. Seeing an opportunity to destroy an isolated portion of Napoleon’s force, enemy generals could rarely resist temptation. However, upon engaging the lead corps, they found themselves in an escalating battle as more and more of the French corps arrived, drawing more and more of the enemy force into the battle.

We can put it another way - if Napoleon simply appeared on the horizon with his entire force, well over 150,000 men, most generals would have thought twice about engaging him in pitched battle. But if, instead, the enemy general found himself attacked by a mere 30,000 men, then he would rationally take the battle and attempt to crush this manageable French force - only for the entire mass to arrive one corps at a time, bringing him into a totalizing battle that he had not bargained for. In this way, Napoleon could bring his enemy into battle by escalating the engagement, rather than beginning all at once.

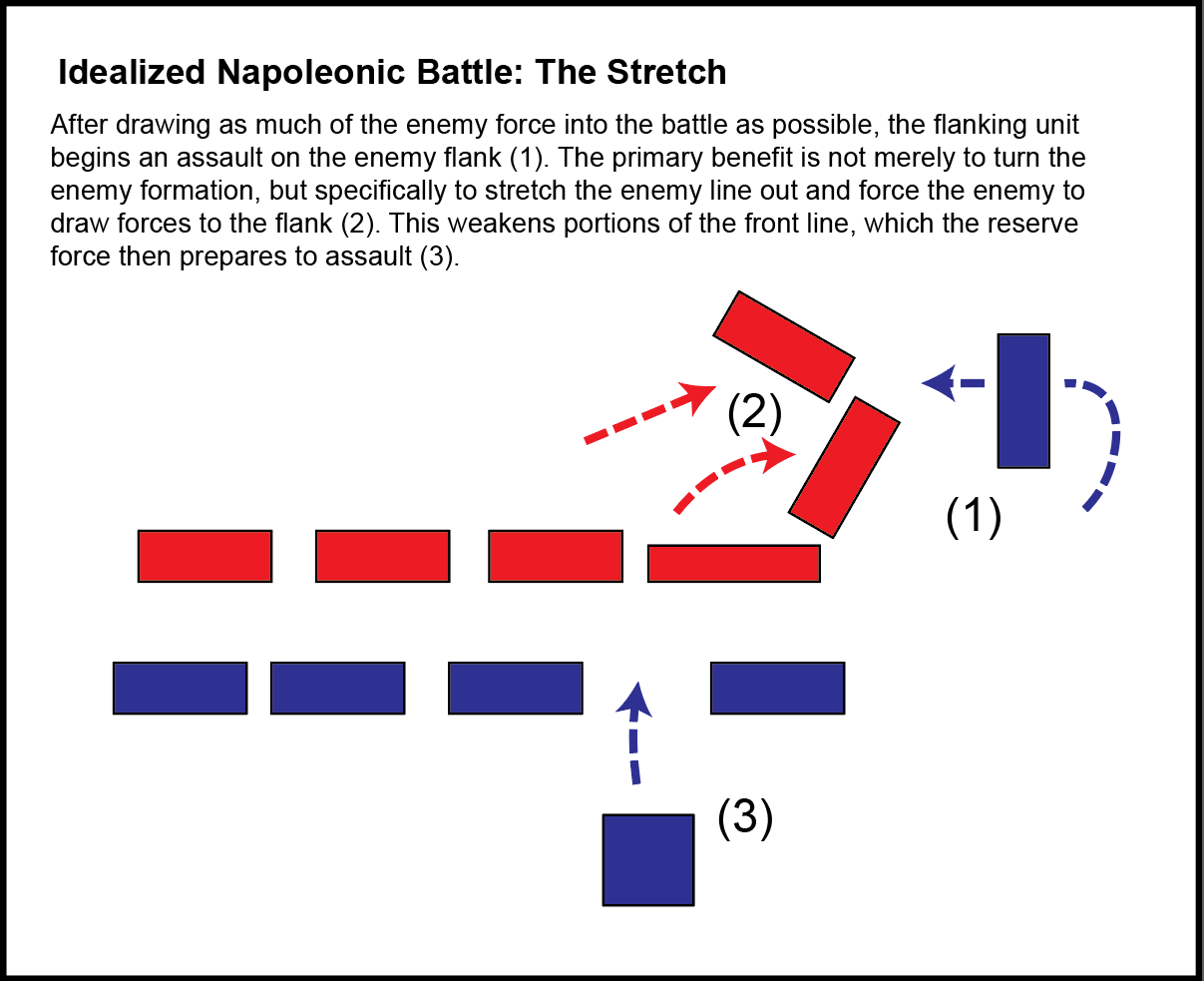

Upon engaging the enemy army, Napoleon’s priority was to draw as much of the enemy force directly into the front lines as possible. He achieved this by making a direct frontal attack with massed infantry lines, in essence creating the impression of an attritional line battle. With the enemy fixated on the frontal attack, two maneuvering forces were held in reserve: a flanking force, which would be sent on a turning march toward the enemy flank, and the crucial ingredient, a reserve force which would be held until the last moment to launch a decisive attack.

Once the enemy was fully committed to the battle, Napoleon would unleash his maneuvering force against the enemy flank. This was a moment of great danger for the enemy army. No elaboration is needed to explain the danger of a flank being turned - Frederick demonstrated the principle fully at Leuthen. However, unlike at Leuthen, for Napoleon the flank attack was rarely and end unto itself. Rather, it served the purpose of stretching out the enemy line - forcing him to pull forces off the line and commit whatever reserves he had remaining to shore up his flank.

Napoleon rarely fought battles aimed at encirclement. Rather, his flanking and turning moves were designed to stress the enemy’s battle line by forcing them to stretch it ever further to keep their flank secure.

Any halfway decent general, without question, would react with great urgency to the French flanking move. Units would be pulled off the line, reserves committed, and all effort would be taken to shore up the flank. But in doing so, the front line would be denuded of strength, and a weak point or hinge would arise. Napoleon called this stretching and thinning of the enemy front “the event” - the precise purpose of the battle. This was the moment where Napoleon’s indefinable sense of battle was most apparent - he would stand, scrutinizing the field, watch in hand - waiting to give the order.

At the moment of Napoleon’s choosing, the artillery batteries would lay a massive barrage on the selected weak point in the enemy’s line, and the reserve assault force would rush forward. The selected point of contact was assaulted with a concentrated mass of both heavy cavalry and infantry columns, blasting a hole and pouring into the enemy rear. Light cavalry rushed through behind the assault force, and the entire battlefield came to resemble a dam bursting, or a river spilling its banks. Napoleon himself likened this decisive attack to “the one drop of water which makes the vessel run over.”

This basic approach to battle, though modified and adapted endlessly depending on circumstances, was the rough blueprint that Napoleon used to defeat enemy after enemy for well over a decade. In the simplest sense, his goal was to methodically stretch out the enemy force, tinkering with the geometry of the field so that the enemy was forced to denude and weaken some point of his line, and then send a reserve force smashing through that weak point. This is a conceptually simple approach to battle - but the difficulty (and by extension the practical display of Napoleon’s skill) lay in successfully predicting which portion of the enemy line would be weakened, and “feeling”, as it were, the correct moment to launch the decisive attack.

Austerlitz: Napoleon’s Immortal Battle

Napoleon’s most famous victory, at the Battle of Austerlitz on December 2, 1805, serves as an eternally useful demonstration of the Napoleonic art of war, because it illustrates the two synergistic elements of Napoleon’s success: his system of warfighting, and his preternatural gift for sensing and comprehending the battlefield - for predicting what his enemies would do, cajoling them into acting the way he wanted, and punishing them for their mistakes at the opportune moment. In many ways, Austerlitz was a fairly straightforward variation on his classic approach to set piece battle, displaying all the basic motifs, but with several delightful and brilliant twists.

As always, Napoleon was under intense pressure to force and win a battle. His virtuoso Ulm campaign had wiped an Austrian army off the board and left the road to Vienna wide open, but new problems quickly arose in the form of Russian armies arriving in theater and linking up with the remaining Austrian forces. Strung out deep in enemy territory, with the combined Austrian and Russian armies lurking, Napoleon needed to find, fight, and destroy as much of their fighting mass as possible to bring a resolution to the campaign.

There were, however, two problems. The first was the classic numerical discrepancy, with the Austrian and Russian coalition force outnumbering Napoleon about 90,000 to 72,000. This manpower edge was not completely overwhelming, but the allies did have a potentially catastrophic advantage in artillery, with 318 cannons to Napoleon’s 157. Furthermore, Napoleon could ill afford to get involved in a costly attritional struggle, because there was a looming threat of Prussian involvement in the war. He therefore needed to engage and destroy the coalition army without unduly draining his own fighting power, to preserve combat capabilities to deal with the Prussians, should the need arise.

The second problem was that it was Napoleon who needed to force a battle, and the Russian commander - Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov - knew it. Kutuzov was a cautious general who wanted to slow walk the campaign, and was not overly eager to get into a set piece battle with the French. Napoleon therefore needed to contrive a way to force a battle with a numerically superior opponent.

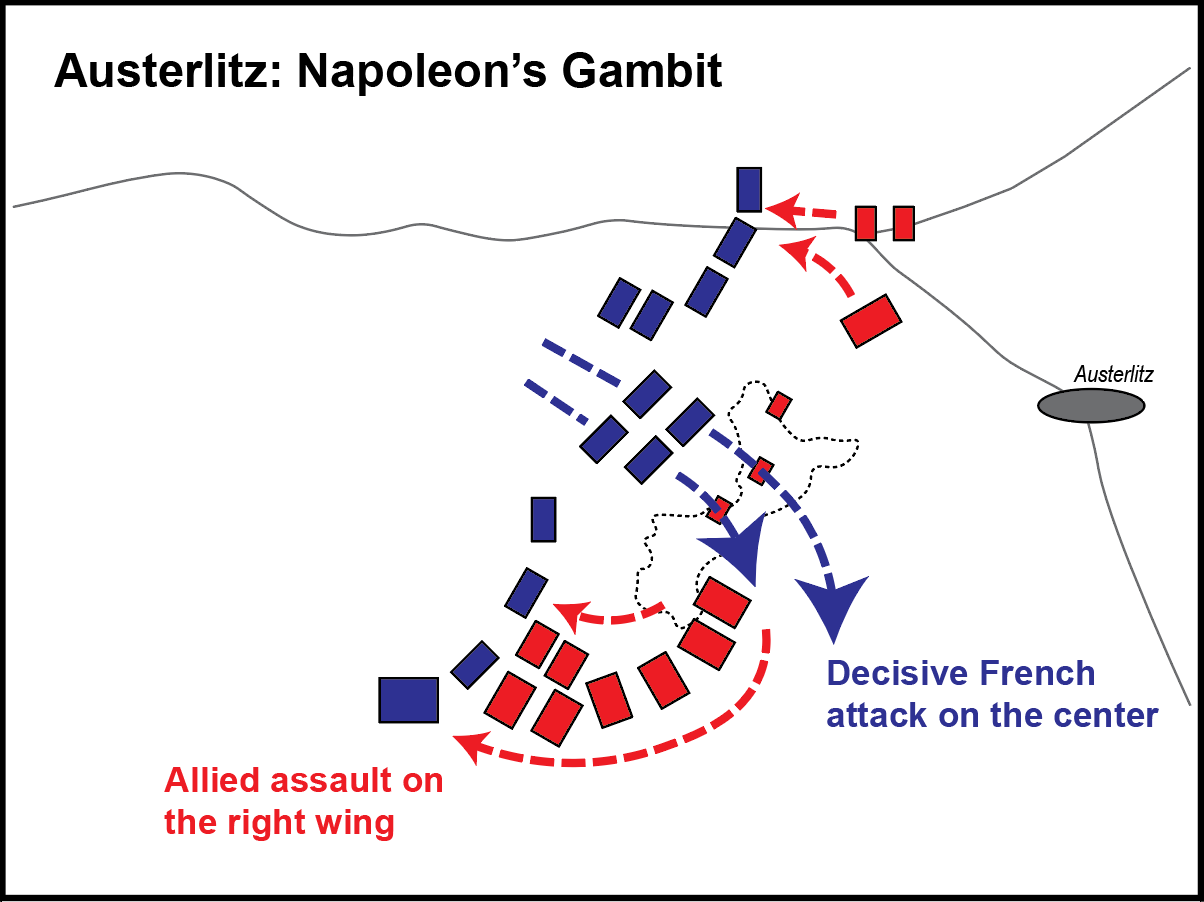

The solution, as always, was to use the speed and ambiguity of the corps system to force a battle. Napoleon flew ahead, advancing to the town of Austerlitz in direct proximity to the enemy coalition’s staging areas - but because the corps arrived one at a time, his force appeared weaker than it was, drawing the enemy in with feigned weakness. Napoleon further dramatized the notion that he was weak and fearful of battle by requesting negotiations and making a show of trepidation and hesitancy with the Russian envoy. To sweeten the deal and fully cajole the enemy into giving battle, Napoleon decided to grant them a powerful positional advantage. The field of battle at Austerlitz was dominated by a formidable hill called the Pratzen heights. In the approach to battle, Napoleon had intentionally abandoned the heights to the Russians for the purpose of feigning weakness and drawing the enemy in. The ruse worked insofar as it convinced the Austro-Prussian force to give battle, but the French now faced an army with a significant advantage in firepower, anchored on high ground.

A French flanking maneuver was ill advised in this situation. In control of the Pratzen heights, the Russians were in position to spot any move towards the flank. Napoleon, therefore, contrived a different way to achieve his goal of stretching and thinning the enemy center. In this case, he deliberately created the impression of a weak right wing. Tempted by the possibility of crushing Napoleon’s wing and cratering in his position, the Russians began moving forces towards the right to reinforce the attack there, denuding their center and creating a dangerously thin line.

Napoleon’s decision to use the right wing as bait to draw the enemy mass across was well thought out and cleverly implemented. The right wing was a natural target for the allied coalition, because the road to Vienna lay to the southwest - that is to say, on the French right. This meant that rolling up the French right flank would not only collapse Napoleon’s army, but also cut off his line of communication and retreat. All of this made the right wing a juicy target, and Napoleon put it on a silver platter by using a single infantry division - a mere 10,000 men, to defend more than two miles of of front.

Napoleon’s plan was predicated on two concealed concentration of troops. The first was Marshal Davout’s force of some 6,600 men, who came up behind the right wing to strengthen it once the enemy attack landed. Davout’s forces were out of the enemy field of vision, creating the impression that the right wing was weaker than it really was. The second concealed concentration, however, was the mass that Napoleon intended to use to win the battle. Cleverly concealed on the transverse side of hills, Napoleon massed two infantry divisions (17,000 men) under Marshal Soult, along with a cavalry reserve, a crack grenadier division, and the Imperial guard - all in all, something like 30,000 men, massed in the center but out of the enemy field of vision.

The paradox of Austerlitz, then, was that although the Russians and Austrians were perched atop a hill with an extensive field of vision, they began the battle without any realistic sense of Napoleon’s deployment. They could see the thin right wing and not much else, and immediately began moving troops away towards the French right without any clue in the world that Napoleon had a powerful mass in the center, just waiting to strike.

Tempted by the apparently easy prospect of smashing Napoleon’s right wing and rolling up his entire line, the allies began moving much of their fighting mass off the Pratzen Heights in the center to attack the right. In the end, nearly 60,000 allied troops - a full two thirds of their force - were allocated to the right wing, leaving their center precariously weak. Napoleon could see them moving off from his command post - he watched through his spyglass as column after column streamed away towards his right wing. Watching from a distance as the enemy center slowly thinned out, he famously predicted “One sharp blow and the war is over”, and ordered the attack.

Russian command on the Pratzen Heights was manically focused on overwhelming what they perceived to be a fatally weak French right wing. They were therefore quite surprised when they looked up and saw French columns charging up the hill towards them. With all the allied reserves in the process of streaming off towards Napoleon’s right, there were simply insufficient forces on hand for the allies to stabilize their line, and the French broke apart the allied center, precipitating a total rout.

It is easy for us to dismiss Austerlitz as some sort of very obvious trap. Of course Napoleon was planning to attack the center, we say. Of course the weakened right wing was just bait. Could it be more obvious? And yet, the scheme utterly confounded a staff of Russian and Austrian generals with extensive military experience. Surveying the battlefield from their lofty command post atop the Pratzen Heights, they had good reason to assume that they had a comprehensive look at the field and knew what was going on. It was their own bad luck that Napoleon had hidden his assault force in an impression on the transverse side of a hill - perhaps the only suitable place where they could be hidden from the enemy’s view. We can say, perhaps, that the coalition force badly mismanaged the Battle of Austerlitz, and we would probably be right. And yet in the final analysis, here was Napoleon, after years of war, still a step ahead of his opponents, confounding them yet again, destroying yet another army and forcing yet another frenzied retreat. What more needs to be said?

Napoleon called Austerlitz the finest battle that he ever fought. It was, to be sure, a decisive victory. The allied army lost over 35,000 men killed and captured, at the cost of less than 2,000 irretrievable French casualties. Yet, from a schematic perspective, what made it so wondrous was how delightfully simple it was, following Napoleon’s general system of battle perfectly: stretch them out, then attack the thin part with a force held in reserve specifically for that purpose. What made the entire scheme work so perfectly was Napoleon’s preternatural sense for battle. At virtually every phase, the enemy did precisely what he expected them to. He abandoned the Pratzen heights, knowing that it would lure them into accepting battle, and then he created an impression of weakness on his right wing, knowing that this would in turn lure them away from the center. Once again, Napoleon was seemingly the only man on the field that day who could see everything, account for all the pieces in his head, and weave an accurate and prescient mental picture of the battle as it was fought.

Many people are capable of reading the schematics in hindsight and of understanding the geometry of the battle. In the same way, we can be walked through famous chess games and have the openings and mating concepts explained to us. That is the easy part. Much rarer is the man who can see it as it is happening, amid confusion and adrenaline, much less see it in advance. This is why many people can enjoy chess, but relatively few can be grandmasters, and even fewer can be world champions. Similarly, Austerlitz has many admirers but only one practitioner - only one who could sense, as if supernaturally, the entire unfolding situation, and synthesize the many moving parts into one seamless whole.

Le Bataillon Carre

Austerlitz was an exemplary application of Napoleon’s preferred system for fighting set piece battles - drawing the enemy into pitched battle with the full mass of his army, distorting the enemy line with positional manipulation, and then launching a heavy attack directly at a weak position. This was the general shape of Napoleonic battle whenever he managed to engage the enemy mass.

On occasion, however, this system was not applicable, because it was not possible to engage the enemy mass in a conventional field battle. This could occur for multiple reasons - either because the enemy army could not be located and pinned down for a static battle (perhaps because the enemy was also in motion), or because the enemy force was divided.

In other words, we have spoken thus far of the way Napoleon used movement and ambiguity to bring the enemy to battle - but what was the Napoleonic response when the enemy himself was in motion and ambiguous?

In these instances, the wonderful flexibility of the Napoleonic corps system became apparent. Napoleon expertly utilized a formation known as Le Bataillon Carre. Literally, the Square Batallion, this referred to a maneuver formation which spaced the corps out in at balanced distances so that each was no more than a day or two’s march from its neighbors. Kept in communication with each other via cavalry, this allowed the entire army to assume a sort of searching posture when the enemy’s exact location and path of movement was unknown.

The equidistance of the corps was vital, as it meant that whichever corps managed to locate the enemy mass could be assured that the others would be able to quickly join it in battle. The roughly square formation also allowed the entire army to turn quickly - if the enemy was detected on the left, for example, the entire army would simply pivot, so that the left hand corps became the advance unit.

The movement of the Bataillon Carre is visualized thusly:

This was Napoleon’s standard method of moving the army towards contact when the disposition, location, and direction of the enemy’s movement were unknown. The corps remained sufficiently dispersed to allow the army to move quickly, but lines of communication and marching distances between them were narrow enough that the army could wheel and respond effectively upon discovering the enemy.

This method of strategic maneuver was put on brilliant display during Napoleon’s 1806 campaign against Prussia. The Prussians, broadly speaking, were habitual bunglers during Napoleon’s heyday - remaining aligned as cautious neutrals during Napoleon’s war with Austria and Prussia in 1805, then declaring war on Napoleon only *after* Austria had surrendered, because they were alarmed on Napoleon’s new levels of influence in Germany. The Prussian King, Frederick William III, attempted to time his entry into the war in such a way as to maximize his leverage, but Napoleon managed to crush the coalition at Austerlitz before Prussia could get in on the action. After Napoleon’s great victory, a war party in the Prussian court - led, allegedly, by the Prussian Queen, Louise - pushed the King to declare war on Napoleon anyway.

In short - and drastically simplifying the complex diplomatic and territorial issues - Prussia opted to watch passively as Napoleon crushed Austria, then jumped to declare war on him after he’d won. So, instead of fighting Napoleon as part of a coalition in 1805, Prussia found itself more or less one on one with Napoleon in 1806. Hardly ideal.

Prussia’s military deployment was almost as confused as their diplomatic choices. The Prussian army, by this time, was a fossil from the days of Frederick the Great. Its formations, tactics, and weapons were unchanged, and at a time when armies were following Napoleon’s lead and organizing division and corps commands, the Prussians still had no staff or permanent order of battle structure higher than the regimental level. This was an army that was nearly fifty years out of date on every level. As if to punctuate its thoroughly archaic nature, more than half of Prussia’s generals were over 60 years old.

Having an un-modern force is bad enough, but the Prussians compounded on the problem because they still possessed the instinctive sense of aggression that Frederick had drilled into them in the 1750’s. They began their war against Napoleon with a somewhat disorderly advance into Saxony, putting over 100,000 men beyond Prussia’s main defensive line (the Elbe River) without clear intentions.

Napoleon, meanwhile, had massed six full corps to the southeast of the Prussian army. He had initially expected the Prussians to keep their forces behind the Elbe, but information began to trickle in that the Prussians had advanced in force and were loitering in Saxony. It proved difficult for Napoleon to extract meaningful information about Prussian intentions. This was, in part, because the Prussians as yet had no intentions - on October 5, they convened a war council which devolved into a multi day shouting match, as the disorganized command debated the merits of various offensive plans.

(This elucidates a fairly straightforward principle of warfare: make your plans before you assume an aggressive posture and march your main field army out into the open country).

Unclear as to where exactly the Prussians were or where they might be going, Napoleon drew up a bataillon carre. This provided maximum operational flexibility. The plan was to march the army in equidistant columns of two corps each and drive straight towards Berlin. If the Prussians did as Napoleon expected and tried to block the French at the Elbe, they would be engaged and destroyed. If the Prussians instead came forward to fight (as indeed they already had) the army could simply wheel in the necessary direction and wrap them up.

As the colossal French army came pounding up towards Berlin, the Prussian army - in a display of passivity that surely made Frederick spin in his grave - simply sat idly in place, paralyzed with indecision as the Grande Armee marched past. Meanwhile, Napoleon continued to receive bewildering intelligence informing him that a large Prussian army was on the left, doing nothing. It was simply… there.

Matters finally came to a head on October 9 when one of Napoleon’s corps - the fifth, under Marshal Lannes - fought a discovery battle (so called because the armies more or less bump into each other) with a Prussian advance guard at Saalfeld. The Prussian force numbered barely 8,000 men and were absolutely crushed by Lannes’ corps, and a Prussian prince was killed in the fighting. The small battle at Saalfeld seems to have jolted the Prussians into action (finally). Suddenly realizing that Napoleon was marching uninhibited towards Berlin, they hastily began to decamp and pull back towards the northeast to take up a defense along the Elbe (as Napoleon had expected at the beginning).

The following events took place so quickly and precisely that they serve as an idealized demonstration of the dexterity of Napoleon’s army, the skill of his corps commanders, and the flexibility of the bataillon carre formation. On October 11, French intelligence finally confirmed for Napoleon that the full Prussian mass was indeed on his left (to the west). On October 12, the orders went out for the entire army to make a left hand turn towards the Prussians. Four corps were to move directly westward to attack the Prussian mass, while the remaining two - under Davout and Bernadotte - were to continue north before wheeling left to come down on the Prussian flank. On October 14, Lannes’ corps led off the attack on the Prussians near the town of Jena.

The Prussians got a full taste of Napoleon’s new way of war, and found that their own style was simply no longer competitive. Lannes came on first with his fifth corps, and the Prussians learned how it felt to watch the battlefield suddenly fill up with French as the other corps arrived - the Seventh under Marshal Augereau arrived on the left, followed by the Sixth under Ney. By the afternoon, the Prussian lines were riddled with holes and formally collapsed.

None of this was particularly surprising. What was surprising, however, was that Napoleon had smashed the wrong Prussian army.

The force that he caught at Jena was not the main Prussian mass - it was a subsidiary force covering the flank, numbering only 38,000 men. Napoleon crushed it, of course, but he also badly outnumbered it. So where was the main Prussian army?

A much larger body - some 60,000 men under the Prussian supreme commander, the Duke of Brunswick - was in fact a ways to the northwest, retreating hastily back towards Berlin. They never got there, because they ran right into Napoleon’s Third Corps, under Marshal Davout, who was executing his orders to flank the Prussians from the north. In short, Napoleon mistakenly pounced on the Prussian rearguard with four full corps, while his flanking force - a single corps of perhaps 27,000 men - mistakenly ran into the main Prussian body near the village of Auerstadt.

Outnumbered by more than 2 to 1, Davout utterly smashed the Prussian army. Davout was himself Napoleon’s best corps commander, and he adroitly demonstrated the full French inventory of skills. The Prussians - who had been attempting to withdraw when they crashed into Davout - stumbled one unit after another onto the field and never put together any sort of concentrated or cohesive battle, allowing the French to simply move through their textbook tactical elements: clouds of skirmishers harassing and disorienting the Prussian infantry; French infantry drifting from column to line as they moved up; artillery pounding away nonstop. When the Prussians attempted an unsupported cavalry charge, the French simply formed squares and bashed them, before moving back to columns for their own attack. Davout handled himself brilliantly all day, slotting his divisions dutifully into a solid line and anchoring himself on the village of Hassenausen. The Prussians, meanwhile, were disoriented from the start, and it only got worse when the Duke of Brunswick was shot through the eye. After wasting their numerical advantage with uncoordinated piecemeal attacks, the Prussians at Auerstadt, like their comrades at Jena, could do nothing but flee.

The dual battles of Jena-Auerstadt, fought on the same day only twelve miles apart, decided the Prussian campaign barely two weeks after it began. What remained of the Prussian army broke apart and was ridden down by the French cavalry, which conducted a legendary pursuit - Prussian morale was so broken that fortresses were surrendered without a fight to detachments of cavalry.

The battle is largely famous for solidifying the reputation of Louis-Nicholas Davout as Napoleon’s greatest Marshal. When Napoleon was told that Davout had crushed a massive Prussian army at Auerstadt, the Emperor (who believed that he had engaged the main Prussian force at Jena) allegedly replied that the Marshal was seeing double. Once the truth was made known, Napoleon was effusive in his praise of Davout - while some claim that Napoleon was resentful of his subordinate’s great victory, publicly this was not the case. One thing that is not up for debate, however, was his great dissatisfaction with Bernadotte, who loitered aimlessly with his First Corps, failing to aid Davout and missing out on both of the day’s battles.

More broadly, the Jena-Auerstadt campaign encapsulated everything that made Napoleon’s military system peerlessly lethal. The bataillon carre and maneuverability of the corps allowed the French to operate efficiently under conditions of extreme ambiguity and uncertainty - without knowing exactly where the Prussians were or where they were going, they were able to advance confidently on a decisive axis, free to flex and turn as needed to take battle. Once Napoleon knew that the Prussians were on his left, he simply turned the army that direction and got his battle only a few days later. The self sufficiency of the combined arms corps furthermore allowed the French to fight a double battle, with Lannes attacking and pinning the Prussians at Jena while he waited for the other corps to arrive, and Davout putting on a clinic by mauling a Prussian force that outnumbered him decisively.

For Prussia, the defeat of course meant subordination to Napoleon, but it also provoked a profound sense of humiliation and existential despair from a county that, as little as two weeks before, still believed it had one of the best armies, if not the best, in Europe. The indignity and shock of defeat would provoke the institutional reforms that led to Moltke, Schlieffen, and Manstein - but that is a story for a different day.

Central Position and Double Battle

One of the peculiar twists of the Jena-Auerstadt campaign is the fact that Napoleon accidentally implemented an operational scheme that he frequently used intentionally. The key is that, at Jena, Napoleon did not know that the Prussian force was divided into two large masses. He believed he was attacking the entire consolidated Prussian army. However, despite not understanding this, the battles mirrored the standard Napoleonic response to facing a divided enemy force.

Napoleon always wanted to attack and destroy the enemy’s main field army - so how could this be achieved when the enemy army was divided into multiple centers of gravity? Of course it was always possible to just choose one and attack, but this raised two possibilities, both of which were concerning: either the second army might converge on the field to aid the first (potentially flanking the French), or the second army might escape, saving much of the enemy’s manpower.

It was therefore important both to keep the second enemy army pinned in the theater, so that it could be attacked as well, while also keeping it at a distance, so the two armies could be destroyed one at at time.

To meet these goals, Napoleon favored an operational concept that we will call the strategy of double battle and central position. This was an approach that he utilized on many occasions throughout his long career.

On the approach to battle, Napoleon would attempt to keep his army (perhaps in a bataillon carre) in a central position. This maximized the army’s freedom of movement and flexibility, by permitting it to attack either enemy body. Once the army advanced to within striking distance, it capitalized on the fighting power and mobility of the corps. A single corps would strike at one of the enemy’s bodies, engaging it with modest intensity so that it could be kept pinned in place and paralyzed, while the remainder of the army swarmed the second body to destroy it. After destroying it, the army would wheel back to rescue the pinning corps and attack the first body.

The use of a single corps to pin and paralyze one of the field armies allowed Napoleon time and time again to handle larger, variegated fronts. The key, as always, was that the French were almost always far more mobile and precise in their movements, which would allow them to pounce on the enemy armies before they could unite.

The strategy of double battle, however, suffers a systemic difficulty. Because the plan centers around wheeling quickly off the first battle to attack the second enemy army, it lacks the energy to pursue and exploit the first victory. In other words, having defeated and chased off Army B, the French immediately turn towards Army A - potentially giving Army B the time and space to reorganize.

One of Napoleon’s most famous battles demonstrates how great this potential danger could be. We speak, of course, of the Battle of Waterloo.

During the Waterloo campaign, Napoleon faced two dispersed enemy forces - the British under Wellington, and the Prussians under Blucher. He responded by attempting to implement the strategy of double battle almost precisely as we described it above. Viewing the Prussians as the greater threat, Napoleon attacked and beat Blucher at the Battle of Ligny, while ordering Marshal Ney to pin the British near Waterloo. This describes Phase 2 of the above graphic precisely.

Two things went wrong, however. First, the French were too slow in wheeling away from Ligny to attack Wellington. Napoleon spent a day in indecision, and the beginning of the French attack at Waterloo was inexcusably delayed. Secondly, there was no proper pursuit of the defeated Prussians after Ligny due to insufficient French cavalry. The Prussians were able to retreat from the field with much of their force intact, and Blucher was able to appear at Waterloo two days later with a reconstituted and reainforced army. Thus, instead of defeating the two coalition armies separately as the strategy of double battle suggests, Napoleon was himself defeated when they managed to unite and concentrate on a single field.

Why Napoleon was Defeated

Napoleon’s historical legacy remains a matter of debate. In his lifetime, he was the subject of intense caricature and propaganda by his enemies, who portrayed him as a diminutive and petty tyrant. This is the image that has survived to this day, and the one thing that most people think they know about Napoleon is that he was short.

Given his ambitions of establishing a continent spanning empire, Napoleon has at times been compared to Adolf Hitler, but the comparison is a poor one. While Napoleon was no saint, and certainly prone to megalomania, there was nothing intrinsically criminal about him. He generally tried to bring stability, rational laws, and security to the lands he conquered, and it is a testament to his reasonableness that his enemies left most of his reforms in place after his defeat.

The crucial factor to consider, when evaluating Napoleon as a moral agent, is the fact that he did not start his wars. Republican France had been at war for a decade by the time he came to power, and indeed he came to power precisely because the country was destabilized and exhausted. Napoleon was not a man who sought political power so that he could unleash war - he was given political power to bring resolution to a war that was already unleashed. He thus saw himself as the man who could bring security to France and finally bring peace to Europe through his own prodigious skill on the battlefield. This was megalomaniacal and egotistical to be sure, but motivated by the quest for stability, not a lust for bloodshed.

In the end, Napoleon ran into a problem - he kept winning battles. Every victory seemed to push French power further and further out, creating more resentment and stretching resources ever thinner. Yet, because Napoleon was in the final analysis a military man, for whom battle was the motivating animus of political life, there was no other way to resolve geopolitical problems.

By 1812 Napoleon had pushed French power to its absolute limit. He had won a stunning series of titanic victories, but those victories brought burdens. Namely, Napoleon now had to contend with three different geopolitical strains:

The financial-naval power of Britain

The military-logistical power of Russia

The diplomatic strain of maintaining control over Germany and Italy.

In particular, France simply lacked the resources to wage a protracted struggle with both Russia and Britain, especially because these two enemies required very different forms of power projection to combat.

In the Russian campaign, Napoleon’s military system reached its limit. Predicated on rapidly attacking and destroying the enemy’s main field army, the system broke down when confronted with an enemy that could simply retreat for hundreds of miles before giving battle. After being drawn deep into the Russian interior, Napoleon could achieve no political objectives. The Battle of Borodino bloodied the Russian army, but did not force a Russian surrender. Napoleon was the master of battle, but here at last - deep in the Russian heartland - battle betrayed its master, and would yield no decisive result.

The withdrawal from Russia devastated Napoleon’s military capacity - not in manpower, but in horses and cannon. French horses died by the thousands due to hunger on the winter road out of Russia, and as they died the cannons that they pulled had to be left behind. By 1813, Napoleon had rebuilt his infantry force to acceptable levels, but his cavalry and artillery arms were left in a permanent state of weakness that crippled the Grande Armee.

Even so, bloodied and weakened, Napoleon remained the best commander in the world. His enemies approached him with trepidation and uncertainty. He only suffered genuinely decisive defeats when outnumbered by prohibitive margins, as at the Battle of Leipzig, where he was outnumbered at 2 to 1 by the combined armies of Prussia, Austria, and Russia. His final act at Waterloo required a combined Prussian-British army to finish him off - and even at the very end he made his enemies sweat. At the climax at Waterloo, Wellington told his aides that either night or the Prussians needed to arrive soon to prevent yet another French victory.

In the end Napoleon was undone because France simply could not bear the geopolitical burdens that it had assumed. There were not enough horses, not enough cannons, and not enough men. Still, his legacy as a military practitioner is without equal. He was not infallible, of course, but across multiple decades of war, in disparate environments and frequently outnumbered, he almost always won, and even in defeats his enemies usually suffered more casualties than he did.

Perhaps no figure since Alexander the Great was so centered on battle, deriving all of his political fortunes from the iron dice. Even from a distance of nearly 200 years, Napoleon is a captivating figure, and a peerless general. He remains the favored son of Ares, and the very incarnation of the spirit of battle.

I knew little of Napoleon's battle skills before reading this article. Thoroughly enjoyed the dissection of military tactics and now have a lot more respect for the French Leader.

"This elucidates a fairly straightforward principle of warfare: make your plans before you assume an aggressive posture and march your main field army out into the open country"

Is this a comment on the SMO?