It is probably not a good sign when an article has to begin with an editorial note that breaks the fourth wall, but here we are. I have analyses of the frontline in Ukraine and a new entry in our naval history series currently in the works, but I’ve been derailed by a challenge that emerged from Twitter (I refuse to call it X) which I’ve been unable to shake out of my mind. People were arguing, as they seem to endlessly do, over what Germany could have done to win World War Two. This is a sort of evergreen topic that is easy bait for engagement, but I had an irresistible urge to give it a treatment of my own.

My motivation, as such, is largely the persistent myth that Germany lost the war when it delayed its offensive to capture Moscow in 1941. This is a grossly misunderstood topic, which assumes unrealistic German freedom of action at the critical moments in August and September 1941. In fact, Germany had no possibility of moving on Moscow earlier than it did. Furthermore, the obsession with Moscow obfuscates the real crisis facing the Wehrmacht, which was the attrition of its most important units, a shortage of replacement personnel, and fuel shortages. So, rather than falling back on the popular motif that the war was decided at the gates of Moscow, we will look more holistically at the crisis of the Wehrmacht and plot a better course.

To keep such analysis grounded in some sense of realism, we will try to speculate about German decision making within their historical constraints, particularly as it relates to manpower, logistical lift, and military intelligence. In other words, we will not alter the strength of the original German force or presume any foreknowledge about the USSR’s reserves. We will, however, examine ways that the German Army could have greatly increased its force generation and logistical strength, based on solutions that they adopted later in the war. We will demonstrate that it was reasonable for German leadership to have “pulled the trigger” on such measures much earlier than they actually did. Thus, while we will not award Germany more forces than they were able to mobilize in the aggregate, we can demonstrate that it was reasonable for Germany to have frontloaded mobilization efforts. We will also do our best to treat the maneuver scheme realistically, and not assign objectives that were far beyond the striking reach of the army. The result is an alternate version of 1941 that, while not probable, was at least possible, and this will have to do.

Preventative War: Barbarossa’s Strategic Logic

Any discussion of the Second World War which asks “why” Germany lost will almost immediately devolve into the cliche of Hitler’s great strategic bungle: the big mistake was attacking the Soviet Union in the first place.

As a groundwork for the broader discussion of Barbarossa, and at the risk of making an apologetic for the single most destructive and violent war in recorded history, it is not actually difficult to understand that the German invasion of the Soviet Union was not only strategically defensible, it was perhaps the only possible course of action given the broader strategic crisis facing Berlin.

It is relatively common for Barbarossa to be defended on the grounds that it was a “preemptive strike”, operating under the assumption that Stalin was preparing his own ground invasion of the Reich. There are elements of truth worth following there, but in general such discussions fail to differentiate between “preemptive” and “preventative” war: similar, but distinct concepts with important nuances. Germany’s attack on the Soviet Union was preventative, but not preemptive, and understanding the difference is worth the ink.

The difference between preemptive and preventative attack is primarily one of timetable. The term “preemptive” is used to denote a military operation undertaken in anticipation of an imminent threat from the enemy. This stands in contrast to preventative war, which implies war for the purpose of preventing an expected conflict in the future, at which point the enemy is projected to enjoy more favorable circumstances and force ratios. The difference largely reduces to a question of freedom of action and the immediacy of the threat. Preemptive action is, to a large extent, forced by the prospect of an imminent enemy attack, while preventative war is undertaken somewhat more voluntarily in order to prevent the long-term strengthening of the enemy. While preemptive action is forced by a specified immediate threat, preemptive war is predicated on longer-term strength calculations and the fear that the other party will initiate war at an unspecified later date under more favorable conditions.

In this case, there was certainly no plan for an imminent attack by the Red Army. While a host of circumstantial evidence is offered to buttress the idea that Stalin was planning an attack on the Reich, it generally founders on a misunderstanding of Soviet military thought. It is true that the Soviet military vocabulary was offensive-minded, but this is largely because the Red Army had a strong cult of the offensive which presumed - as if by magic - that any enemy attack could be quickly absorbed, allowing Soviet forces to quickly go over to the attack in the event of war. It is undeniable that Soviet leadership was anticipating war with Germany at some undetermined date in the looming future, but this is entirely different from claiming that the Soviet Union had concrete plans to attack Germany in 1941.

To take but one example, a common data point raised to support the Soviet attack hypothesis was a May 1941 proposal by Zhukov which sketched out a secretive deployment of the Red Army for offensive operations against the Wehrmacht. The proposal was real enough, but mention is usually neglected of the fact that the Zhukov deployment plan was never signed off on by Stalin, nor was it the deployment scheme in use by the Red Army on the eve of war.

More to the point, the proper establishment of the timeline makes it clear that Hitler and the Wehrmacht prepared to attack the USSR on their own recognizance, rather than in response to a perceived imminent threat. Hitler’s decision to attack the USSR is usually traced to a July 31, 1940 meeting at the Berghof where he for the first time declared his intention to smash the Soviet Union “once and for all.” The first operational sketches for the campaign had already been submitted by Major-General Erich Marcks on August 5, 1940, and the operation had received its designation of “Barbarossa” in December.

In contrast, data points suggesting Soviet aggression generally date from the following year (1941, the year of the invasion). In March, German military intelligence began submitting reports related to Soviet mobilization in the border regions. Moreover, on March 14, 1941, German Foreign Armies East noted in its situation report that the Red Army was in a state of partial mobilization. Observing the ongoing Soviet deployments throughout the spring, in May Hitler and the Wehrmacht operations staff acknowledged that Red Army formations were much larger than originally anticipated, and that it was possible that the Soviets might take their own preemptive actions to disrupt the staging for Barbarossa.

Taken on aggregate, three key facts emerge which ought to strongly disabuse us of the idea that a Soviet attack on Germany was planned for 1941. First, German planning for Barbarossa began in the summer of 1940, months before German intelligence began delivering steady reports about Soviet accumulation of forces near the border. Secondly, in the spring of 1941 German intelligence still assessed that the Red Army was in a state of partial mobilization; to the extent that they feared a Soviet attack, they were concerned about limited Red Army operations to disrupt preparations for Barbarossa. Third and finally (and much more to the point), as of yet there is no documentation of an anticipated Soviet strategic offensive from either side - either in the form of German intelligence warning of a Soviet attack, or Soviet plans for such an operation.

Barbarossa was not a preemptive strike. This does not mean, however, that it did not have fundamentally sound strategic logic as a preventative war.

Germany’s problem, as such, was not that Stalin was preparing to attack the Reich in 1941, but rather that the USSR’s strength was increasing over time relative to Germany, while both ideological and geopolitical contradictions made it essentially impossible to craft a stable accommodation between the two states in the long run. Particular friction points lay in both the terms of German-Soviet trade, and escalating friction over spheres of influence in the limitrophe states.

The structural problem from the German perspective was that trade with the USSR was broadly predicated on swapping German technology for Soviet natural resources. In the short run, this did give Berlin a way to circumvent the British blockade, but the basic issue was that the commodities brought in from the Soviet Union - grain, oil, and metallurgic inputs - were consumables which did not strengthen Germany in the long run: on the contrary, they put Germany in the painful position of abject dependence on Moscow. The Soviet government, for its part, was hardly shy about emphasizing this point. In 1940, the USSR temporarily suspended grain and oil exports to Germany in response to a delay in German coal shipments. The threat of delayed or cancelled Soviet deliveries was so severe that Goring issued a directive stipulating:

All German departments must proceed from the fact that the Russian raw materials are absolutely vital to us… According to an explicit decision by the Fuhrer, where reciprocal deliveries to the Russians are endangered, even German Wehrmacht deliveries must be held back so as to ensure punctual delivery to the Russians.”

This sense of ongoing and interminable dependence on an ideological anathema like the USSR was felt to be essentially intolerable, and there was little prospect of relief. A report from the Reich department for economic development concluded that, even if the British could be ejected from North Africa and the Middle East (bringing those resource fields under German control), the Reich would still face shortages in 19 out of 33 identified vital raw materials. In other words, even the successful resolution of the war against Britain could not be expected to bring economic self sufficiency.

Meanwhile, Germany shipped a steady stream of sensitive technology and industrial capital to the Soviet Union. In 1940, the Soviets demanded (and were granted) delivery of a complete plant for the production of synthetic rubber and fuel, followed by a demand that they be given IG-Farben’s innovative process for the producing toluene, which was a critical input in Germany’s high grade aviation fuel. German tank, bomber, and artillery prototypes were also shipped off to the USSR. This was the price of grain.

In short, Stalin had Hitler over a barrel. There was absolutely no question that the German war economy could not function without Soviet raw materials, but - lacking real leverage over Moscow - Germany had no choice but to send a steady flow of sensitive industrial secrets, military prototypes, and machine tools to the east. Germany had evaded the British blockade, at the cost of turning itself into an economic vassal of the Soviet Union. This was an almost exact reversal of the stated objective of a self sufficient German economy, and even more importantly it promised a long-term increase in the USSR’s power as it absorbed German industrial technology.

Matters truly came to a head, however, with the visit of Vyacheslav Molotov to Berlin in November 1940. The Molotov-Hitler summit was perhaps the last real chance for Germany and the Soviet Union to reach some sort of stable coexistence, and in this it was an abject failure. The general point which emerged, as if it were not already obvious, was that Moscow had enormous leverage over Germany which Hitler could not reciprocate. Despite a grandiloquent attempt to derail Molotov with rants about the hateful “Anglo-Saxons” and a fanciful encouragement for the USSR to seize British India (it was not clear how or why this could be achieved), Molotov remained tightly focused on Europe and presented the Germans with a series of demands which amounted to a geopolitical checkmate.

Among the demands stipulated by Molotov, the USSR insisted that Germany withdraw all her troops and military advisors from Finland, accede to Soviet occupation of the Turkish straits, and acknowledge Bulgaria as a “security zone” of the Soviet Union, implying Red Army occupation at a near date. For obvious reasons, this was a nonstarter for Hitler, as it implied further Soviet encroachment on vital German trading partners. Finland, for example, was an irreplaceable source of nickel and timber, while a Red Army position in Bulgaria would put Stalin’s forces right up the road from Romania’s oil fields, which were Germany’s only significant source of non-Soviet petroleum.

When one considers Molotov and Stalin’s demands of late 1940 in the broader context of the German-Soviet relationship, it becomes extremely clear that Germany was geostrategically cornered. The core dynamic of this relationship was Germany’s abject dependence on Soviet raw materials, and Stalin’s attempt to muscle in further on Finland, Bulgaria, and Romania threatened to exacerbate this dependence. Hitler had few levers that he could lean on to counter this, particularly because he (still locked in a war with Britain) lacked options, while Stalin (who was not nominally in a state of war) had time on his side.

This, then, was the basic logic behind Operation Barbarossa, and it was sound enough. Germany had fought its way into a strategic trap, conquering vast territories in Europe which simply lacked the natural resources to bring the economic self sufficiency that Hitler craved; instead, he was now economically dependent on Moscow and faced the prospect of further resource strangulation as Stalin pressed his demands for further encroachment into the Baltic and the Balkans. Hitler lacked commensurate strategic or economic leverage to push back, and so he chose to lean on the strongest lever in his hands: the Wehrmacht.

It was clear that no arrangement could be contrived that could bring a stable coexistence between the USSR and the German Reich, given the vastly disproportionate resource bases of the two countries. Facing the prospect of a future war (perhaps in 1942-43) under less favorable circumstances, or an immediate strike against a Red Army that was still in the process of reorganization and armament, Hitler chose preventative war.

Force Generation and Total War

At last we come to the interesting part, where we probe alternative realities. How might Germany have defeated the Soviet Union, if this was even possible at all?

Any discussion of Germany’s defeat in the east and its causes must begin with one of the greatest military intelligence misfires of all time: the German assessment of Soviet reserves and force generation potential. The totem figure, which I cite frequently as the nucleus of Germany’s great disaster, was the assumption (built into the Wehrmacht’s wargaming) that the Red Army could feasibly mobilize 40 fresh divisions in response to the invasion, while the actual number was approximately 800. This 20:1 underestimate of Soviet force generation lay, either implicitly or explicitly, at the heart of Barbarossa's failure and the continual bewilderment expressed by German leadership at the appearance of fresh Soviet formations in the field.

The other side of this question relates to Germany’s own capacity to generate fighting power, both by mobilizing men and managing the wartime industrial economy. Here, however, a significant discrepancy exists in the conventional understanding of the war: a discrepancy which originates in Germany’s abysmal mismanagement of the conflict, beginning in the summer of 1941.

The standard presentation of the war in the east emphasizes the horrendous attrition of the Wehrmacht in 1941 as it was ground down first by a tenacious Soviet defense, followed by a series of Red Army counteroffensives during the winter. The impression is that of a weary and threadbare German Army reduced to a shell of itself. Elements of this story are certainly true, with the ledger revealing that many of the eastern army’s divisions were clinging to perhaps half of their regulation strength. What this story misses, however, is that the Wehrmacht was consistently able to reconstitute its strength and even increase the total number of active personnel - not just in 1942, to recover from Barbarossa and the Soviet winter offensives, but again in early 1943 after the disaster at Stalingrad. Armaments output also rose significantly, reaching its peak in 1944.

Reconciling these contradictory pictures requires probing the depths of German strategic ineptitude, particularly the inability of German leadership to understand the war that they were fighting in the east and their schizophrenic management of human resources. At the core of the issue lay German confidence in a rapid victory over the Soviet Union through a planned blitzkrieg, which left little impetus to plan for a protracted war which would require continued mobilization. When Barbarossa began, German leadership was planning to demobilize personnel for release back into the labor force. Despite the fact that it should have been apparent by July 21st at the latest (a date upon which we will elaborate later) that the war was not going to plan and more manpower would be needed, Hitler and the high command were still operating under the impression that much of the army could be released from service in the coming year. It was not until the spring of 1942, in fact, that Germany began to work seriously on its manpower problems by releasing additional workers for military service, intensifying conscription, and mobilizing foreign workers and POWs to provide needed labor for industry. Furthermore, it was not until 1943 that Germany adopted what might be called a total war economy, with rationalization, tight central planning, and restrictions on civilian production.

A core element of Germany’s botched war, then, was a fatal delay in transitioning to a fully mobilized war economy and wider mobilization of personnel for the army. This dovetailed with misallocation of personnel to ensure that the field army in the east was needlessly starved of personnel. The cause was a deadly amalgam of political trauma and overconfidence. The trauma originated in the First World War, which brought widespread deprivation to German civilians as the economy was fully mobilized for war while being squeezed by a British blockade. While the effects of the blockade are often overstated, in that the German field army remained broadly solvent and adequately supplied, the memory of civilian shortages lingered, and German leadership in the second war was loathe to disrupt civilian production. Simultaneously, Hitler and the high command remained foolishly confident in imminent Soviet collapse and were therefore unwilling to kick mobilization into a higher gear in 1941.

The upshot of all this was that, while the Soviet Union was undergoing a total mobilization of virtually all its human and economic resources (aided by that wonderful instrument of power, the Communist Party), Germany was shockingly lethargic. Hitler did not seriously contemplate mobilizing deferred industrial workers (offset by employing prisoners of war, restricting production of civilian goods, and exploiting the workforce of occupied territories) until March, 1942, and even then the mobilization process proceeded slowly. Given the scale of the war that was unfolding in front of their very eyes, the German failure to launch an energetic mobilization in 1941 stands out as a crucial turning point in the conflict which starved the eastern army of personnel during its crucial window of opportunity.

Any alternative history of the Nazi-Soviet War, then, ought to begin with the suggestion of a much earlier German mobilization. This is particularly appealing because it does not require much speculation: more aggressive exploitation of the manpower reserve relies only on mechanisms that the Germans ended up utilizing in reality. These were capabilities that the Germans demonstrated in 1942-44, and in our scenario, we need only pretend that they were faster to recognize the crisis in front of them and adopt these policies in the summer of 1941.

In particular, the immediate employment of prisoners of war, the rationalization and adoption of a war economy, and the release of protected industrial workers for military service would have freed up nearly 1 million personnel for the eastern army by the end of 1941. This is evidenced by the fact that, on July 1, 1942, total Wehrmacht personnel was some 1.1 million higher than at the beginning of Barbarossa, despite the severe losses suffered over the previous year.

In reality, the Wehrmacht took in a shocking number of replacements in 1942 and reconstituted its fighting power much more effectively than many historians acknowledge. However, this influx of personnel was not efficiently allocated, particularly because the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine were able to successfully lobby for more men. The Luftwaffe, for example, increased its personnel by some 355,000 men between June 1941 and July 1942, with most of the increase occurring in the early months of 1942. Remarkably, Goring’s haul of men came largely on the momentum of increases that were planned before Barbarossa began.

This is emblematic of Germany’s gross mismanagement of its human resources. Before the invasion of the Soviet Union, there were idealistic plans to demobilize army personnel, releasing men into the economy while increasing the strength of the Luftwaffe. By mid-1941, it should have been obvious that the war was going wrong and the army needed every man that it could get, yet German leadership remained unwilling to begin pulling men out of the industrial labor force, and they allowed the Luftwaffe to absorb roughly a third of the increase in the Werhmacht’s total personnel.

One needs to tinker with the timeline only a very little to drastically increase German combat power on the eastern front during its crucial window of opportunity (1941-42). First, by initiating the expanded callup of industrial workers and beginning the transition to a war economy in July 1941 (a date which, to reiterate, I will defend further on), one can pencil in roughly 560,0000 trained reservists released to the army in the latter half of 1941 (in reality, these men were not mobilized until the spring of 1942), which could have been augmented further by restricting the Luftwaffe’s access to personnel in favor of the eastern army. If German leadership had responded with more clarity and appreciation for the crisis that it faced, on the whole at least 750,000 additional personnel could have gone to the field army in the Soviet Union by the winter of 1941 - and all this largely by making the decisions of March 1942 in July of the previous year. The army would have then undergone further replenishment and expansion by calling up the 1942 draft class.

We are taking liberties, of course, with such hypotheticals. The reality was that the Nazi regime was significantly less reactive and unified than its opponent. Hitler lacked levers of control equivalent to those wielded by Stalin, and long after Barbarossa began the German regime continued to see its energies dissipated by feuding fiefdoms. The Luftwaffe and the navy continued to lobby successfully for access to personnel and industrial labor, and in general the leadership group was psychologically incapable of admitting that the planned blitzkrieg was failing. As late as November, there were still illusions that - rather than funneling reinforcements to the east - troops might be withdrawn to Germany over the winter, or even demobilized. As the official German history of the war puts it:

The bureaucracy of the Third Reich was unable to respond in a flexible manner to changes in the military situation. Initially, the political leadership maintained a rigid loyalty to the concept of blitzkrieg. These facts can be demonstrated with particular clarity in the case of the system of deferrals. Despite rising casualty rates in the army in the east during the summer of 1941, the number of deferrals continued its dramatic increase. In September 1941 it reached its highest total of the first half of the war at almost 5.6 million men.

The regime would not be shaken from this stupor until the Soviet winter offensives made the crisis impossible to ignore. If the need for expanded mobilization was the elephant in the room, the winter of 1941-42 was when the elephant grabbed somebody with its trunk and tore his limb off. Action was taken, belatedly, in March 1942 which finally saw the faucet of manpower open. For our hypothetical, however, let us proceed as if Hitler noticed the elephant in July and acted accordingly.

Logistics at the End of the World

The prior segment demonstrated, hopefully, that although Germany faced dire manpower shortages at many moments in the war, it had the capacity in 1941 and 1942 to regenerate its combat power, but was unable to do so in a timely manner due to political neuroses. The Wehrmacht would indeed reconstitute its strength on the eastern front on two occasions, but in 1941 it did not, and consequently it plunged into the winter in a threadbare state.

The second element of German defeat in the east which generally gets headline treatment is logistics. Here, the conversation generally takes two separate tracks. One version of the story treats the logistical breakdown of the Wehrmacht as a matter of German incompetence, as if they simply didn’t contemplate the challenges of supply. This is usually where people get a good laugh at the idea that the German army forgot its winter gear, as if they did not know that it gets cold in Moscow. Another version of the story treats the logistical lapse as a sort of inevitability, as if there was simply nothing to be done in the face of the USSR’s distances, harsh climactic and terrain conditions, and underdeveloped road and rail network.

As is often the case, the truth lies somewhere in between. It is certainly the case that, no matter what the Germans did, it was going to be a difficult lift to adequately supply vast armies in Central Russia. The Wehrmacht simply had an inadequate motorization component to maintain a proper truck lift, and shortages of fuel and rubber (combined with frequent breakdowns due to the poor condition of Soviet roads) exacerbated their organic shortage of motor transport. Supplying the eastern army required a delicate balance of lift via railway, trucks, tracked vehicles, and humble horse-drawn carts, all of which were strained in unprecedented ways in the east.

While it is an inescapable conclusion that German logistics were never going to be fully satisfactory in the east, it must be acknowledged that, once again, dysfunctional management exacerbated the problem. Many of the technical problems with the railways in the east are overstated in popular histories. For example, it is common to note that the gauge on the Soviet track was different than the standard European rail, forcing the Germans to relay the rail lines. This is true, but in fact the conversion of the track was a fairly simple engineering task for German railways troops. By December, 1941, German engineers had re-gauged 15,000 kilometers of track, and had raised the total to 21,000 by May, 1942. Compared to altering the track gauge, the more complicated task turned out to be repairing and building service centers and other railway facilities, but this was accomplished in time as well.

The biggest problem with the rail network in the east was not the difficulty of converting and repairing track, but a shortage of locomotives, insufficient personnel among the railway troops and logistical staff, and chaotic management (which frequently devolved into commanders “hijacking” supply trains for their own purposes). As in the realm of manpower, where the Germans responded lethargically, the remediation of the logistical system was slow in coming primarily due to mismanagement and unresponsive leadership. Amid the general congestion of the rail net, the civilian railway authorities (the Reichsbahn) and their military counterparts (the Eisenbahntruppen) devolved into a toxic mire of finger pointing, jurisdictional competition, and mistrust.

German efforts to strengthen the logistical lift on the railways did not seriously kick into gear until November, 1941: long after the supply situation had become dire, and much too late to benefit the push towards Moscow. It was not until late November that the Reichsbahn was ordered to dispatch additional resources to the eastern army. The subsequent arrival of more railway personnel and 1,000 locomotives almost immediately boosted the daily rail traffic to the front by 50%, and these gains were augmented by the steady release of more locomotives in the early months of 1942. It was not until May, 1942, that Albert Speer was tasked with energetic remediation of the eastern railnet, which he tackled by dedicating more resources to repairing facilities in the east, rationalizing and accelerating unloading procedures, and withdrawing rolling stock from occupied territories in the west. By the summer of 1942, the War Economy Department assessed that rail traffic to the east was adequate to supply the army at the front.

As in the case of manpower for the army, there was hardly a magic button that the Germans could press to instantly provide infinite personnel and supply. Again, however, the lethargy of German leadership in responding to the crisis at the front suggests that things could have been different. Critical decisions, like the allocation of civilian railway resources and Speer’s managerial changes, did not occur for many months after the supply crisis should have become obvious: a delay which can be attributed, once again, to German leadership’s unwillingness to admit that the campaign was not going according to plan.

If German leadership had been more cognitively flexible and responsive to the unfolding military crisis, many of these decisions could have been frontloaded to the summer of 1941. In a world where Berlin admits in July that the war is going to be much longer and more resource intensive than anticipated (a world where Germany is willing to transition to a full war footing before it is too late), more railway personnel, engineering resources, and locomotives could be dispatched over the summer, resulting in a more robust supply lift during the critical autumnal months.

In the case of both the railways and the manpower crisis, the general theme that emerges is that of German leadership which responds only to extreme crisis, particular in the form of the Red Army’s winter offensives. It was only the intense pressure of these winter offensives - which brought Army Group Center to the verge of collapse - which finally jolted Hitler awake and forced a belated callup of reservists from the labor force; similarly, it was only once the supply crisis reached a breaking point in November that Germany began to mobilize additional resources for the eastern railway.

The result was that both Germany’s manpower balance and logistical chain were largely restored, albeit much too late. The rigid belief in rapid victory and looming Soviet collapse left German leadership without the intellectual toolkit to acknowledge the crisis while it was in its early stages. We are left with a remarkable juxtaposition. It is difficult to imagine a state that better embodied total war than Germany in 1944 and 1945 - mobilizing underage youth and old men, cannibalizing virtually every demographic and economic resource as it defied oblivion. Yet in 1941, when the strategic crisis first manifested, this same regime was shockingly complacent about mobilizing additional resources for the eastern army. The German economy did not transition to a full war footing until mid-1943, and during the crucial operational window the eastern army was denied access to critical logistical and manpower resources.

Turning Point at Smolensk

The general impression that we are attempting to make is that, although German resources were certainly limited (and woefully inadequate for a war against two enemies with continent-spanning resources), the Wehrmacht had reservoirs of human, industrial, and logistical resources which were left untapped in 1941, creating a general military crisis in the winter. In general, German leadership intensified the war effort in response to the winter catastrophe, rather than anticipating it with timely mobilization of resources.

The logical following question then emerges: was there a point in 1941 where it was reasonable for German leadership to have comprehended that it was caught in an emerging military catastrophe? Was it possible to discern the elephant in the room before it went rampant? While any treatment of this topic must fairly note the peculiar institutional neuroses of the German regime - driven by both the unique personalities involved and the dissipated and quarrelsome command structure - I argue unequivocally that such an opportunity for course correction did exist.

Specifically, the the second half of July, 1941, presents itself as the moment where the German campaign not only began to go wildly off track, but also the point where the mounting strategic crisis should have become apparent. A somewhat more rational and cognitively flexible German leadership, less blinded by its faith in rapid victory and Soviet collapse, should have course corrected at this point. The fateful period dates specifically to July 21-31.

During this critical period, four important milestones were checked off in rapid sequence:

The Red Army began a broad counteroffensive with newly deployed field armies that the Wehrmacht did not expect to encounter, proving definitively that prewar assumptions about Soviet force generation and reserves were wrong.

German high command, including Hitler, for the first time became divided and uncertain about next operational steps. No consensus could be reached about the shape and priority of following operations.

The critical formations of Army Group Center proved unable to complete keystone operational tasks.

The first glaringly obvious operational misstep of the war was committed, with Heinz Guderian’s panzer group contributing materially to German defeat by attempting to seize and hold the Yelnya Bridgehead (more on this momentarily).

Taken together, late July can clearly be seen as the point where the campaign began to derail at every level. Strategically, German command began to exhibit paralysis and confusion as to how to continue the campaign, while Army Group Center began to sputter both in its operational choices and in the diminishing combat power of its critical formations. This was the moment where a somewhat more rational German leadership group could have and should have held honest internal discussions and responded by both mobilizing additional resources (deploying more rail personnel and assets to the east and beginning the callup of trained reservists in the civilian labor force) and making rational amendments to the maneuver scheme.

The Wehrmacht’s catastrophe unfolded as follows.

The opening phase of Barbarossa is fairly well understood, with Army Group Center (the largest and most lavishly equipped of the three German army groups, with two of the eastern army’s four panzer groups) caught a grouping of Soviet armies in an enormous pocket around Minsk, which bagged hundreds of thousands of prisoners and tore an enormous hole in the Red Army’s western front. On this basis of the victory at Minsk, German leadership made its famous pronouncements that the Soviets had already been practically defeated, with Halder (Chief of Staff of the Army High Command) famously writing in his diary that the war had been functionally won in two weeks, and that farther east the Germans would encounter “only partial” forces.

By July 4th, however, as the enormous pocket around Minsk was in its final stages of reduction, the two key striking elements of Army Group Center - Hermann Hoth’s 3rd Panzer Group and Heinz Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Group - were already departing from the Minsk area, moving rapidly at 45 degree angles to each other. Hoth was driving to the northeast to seize a crossing over the Dvina River, while Guderian was moving eastward towards the Dnieper. Although the general shape of these advances suggested a concentric move towards Smolensk, the combat power of Army Group Center was now subtly dissipating, with two commanders in Hoth and Guderian who had their own ideas at play. However, the danger seemed to be relatively low, given the assessment that the Soviets were incapable of building a new and coherent defensive line. As Hoth would later bemoan, however, “the consequences of an inaccurate assessment of the enemy became readily apparent.”

While we will comment on a few of the operational particulars, the general theme that would now emerge was a strange unwillingness on the part of both key commanders in the field (Guderian perhaps most of all) and the German high command to react appropriately to the discovery of an entirely new grouping of Soviet field armies around Smolensk.

As late as July 6th, key German figures like Hoth and Halder were convinced that they would encounter only partial or “scraped together” Soviet forces to the east. The German situation map for July 4th identifies only two Soviet field armies around Smolensk: the 11th and the 13th, with many of the Soviet divisions marked with the word “Reste”, which means remnants or leftovers, implying partial units that had been previously mauled. By July 12th, however, the German maps depict new armies like the 19th, 21st, and 22nd, to which the 20th would be added a few days later.

These were the newly arriving forces of the Soviet Reserve Army which had been freshly dispatched to reinforce their Western Front (a “front” being the Soviet parlance for an Army Group.) The appearance of what amounted to an entirely unaccounted for army group (with thousands of tanks), ought to have been the moment that German leadership began to awaken to reality and begun acknowledging that they had badly underestimated Soviet force generation, but they did not.

More importantly, the German failure to react to the new Soviet armies around Smolensk occurred at two critical levels of command. At the strategic level, there was no revision of the expectation that the Red Army was collapsing, and consequently there could be no attempt to begin shifting towards a footing for a longer and bigger war by mobilizing reservists and redirecting logistical assets to the east. At the operational level, however, field commanders like Guderian made a series of poor choices which turned the ensuing Battle of Smolensk into a hollow, pyrrhic victory which largely doomed the German war.

The first domino in the emerging operational crisis was a series of Soviet counterattacks on the flanks and joints of the advancing Panzer Groups. A pair of Soviet mechanized corps attacked in the area around Lepel and Syanno (in modern Belarus) near the boundary between Hoth and Guderian’s groups. Although the Soviet attack collapsed with heavy casualties, it compelled Guderian to reroute 17th Panzer Division to fall on the flank of the attacking Soviet formations. Meanwhile, the Soviet 21st Army attacked Guderian’s exposed southern flank, which was dangling out in open space due to the great distance by which Army Group Center had outrun its southern neighbor.

Guderian was utterly fixated on continuing his drive to the east, and he resented the fact that forces on both his flanks were now being diverted by Soviet counterattacks. On July 7th, he ordered that the battles on both flanks be broken off with the enemy “kept under observation”, as he began funneling troops over the Dnieper to drive further east. This greatly irritated Hoth, as there were still strong Soviet forces fighting along their operational boundary. With Guderian’s 17th Panzer Division now departing to drive east, Hoth was left “holding the bag”, as he put it. Furthermore, in his haste to get over the Dnieper as quickly as possible, Guderian bypassed pockets of Soviet troops which were still defending along the river line, and in particular left a strong Soviet grouping behind him at Mogilev. The reduction of these positions would fall to the infantry divisions following in Guderian’s wake, and in turn delayed their arrival at the front around Smolensk.

The German situation map for July 20th already reveals all the ways that this battle was going wrong. Guderian had pushed his panzer divisions over the Dnieper and advanced the 10th Panzer Division to Yelnya, which he perceived as a critical staging ground for the next phase of the objective (aimed at Moscow). Unfortunately for the Germans, Guderian’s fixation on diving for the Yelyna bridgehead had created major problems and marks the first point where German operational choices were clearly wrong.

First and foremost, by pushing his panzer divisions east toward Yelnya, Guderian left the encirclement which was now forming around Smolensk unfinished. Army Group Center’s commander, Fedor von Bock, was aghast, writing: “There is only one pocket on the army group’s front! And it has a hole!” It would take weeks for the Germans to close off the pocket around Smolensk, with Hoth’s panzer group doing almost all of the hard work. On August 1, under heavy pressure from Soviet counterattacks, the encirclement was broken back open. Nearly half of the encircled Soviet troops would escape, with some 50,000 trickling out to the east in the early days of August.

The basic problem was that Guderian was an officer with a strong predisposition for insubordination, who had his own ideas about which direction the campaign was heading. He continued to believe that a thrust directly towards Moscow was the best course of action, and he prioritized holding his bridgehead at Yelnya over essentially every other operational priority. In the closing week of July, with the encirclement around Smolensk still leaking Soviet troops to the east, Guderian would actually shuttle units away from Smolensk into Yelnya, rather than the other way around.

In the end, Guderian’s position at Yelnya turned out to be one of the most counterproductive operational choices of the war. Not only did it directly contribute to a pyrrhic victory at Smolensk, with much of the encircled force escaping, but it also accelerated the attrition of the panzer units in Army Group Center. This happened for two reasons: first, by neglecting the encirclement, Guderian shifted the burden onto Hoth’s Panzer Group, which took correspondingly high casualties. In particular, 7th Panzer Division ended up doing most of the heavy fighting, trying unsuccessfully to seal off the Smolensk-Moscow road.

More importantly, however, the Yelyna bridgehead became a killing field for Guderian’s forces. The bulging salient, some 60 km wide, was subjected to heavy attacks on a 180 degree arc. On July 26, Panzer Group 2’s war diary recorded:

At the fighting around Yelnya the situation is especially critical. The corps has been attacked all day from strongly superior forces with tanks and artillery… Constant heavy artillery fire is inflicting heavy casualties on the troops… The corps has absolutely no shells available… The corps can maybe manage to hold on to its position, by only at the price of severe bloodletting.

Army Group Center would eventually take some 100,000 casualties in August and September in the face of persistent Red Army counterattacks. Of these, a little over 40% came in the Yelnya bridgehead, which was the single most exposed position on the German front. The Germans would eventually abandon the position in September, but only after taking heavy losses and allowing the position to divert resources away from finishing encircled Red Army forces in Smolensk and Mogilev.

In short, the Yelnya Bridgehead cost the Germans valuable material as well as time. As a direct result of Guderian’s indifference towards sealing the encirclements, it took several weeks to stabilize the front and reduce the various pockets, and all the while the forces around Yelnya remained exposed to heavy Soviet fire. Taking the basic ledger of the Yelnya position, Guderian’s decisions cost the Wehrmacht approximately ten days of delay (by prolonging the battle around Smolensk), allowed something in excess of 50,000 Soviet troops to escape encirclement, and greatly increased the attrition of the panzer groups.

German leadership was aware of all these things. Halder wrote in his diary that the fighting around Yelnya had been brutal and was inflicting heavy losses on the German forces holding the bridgehead, and Bock was certainly aware that the Smolensk pocket was leaking. Despite this, nobody at the higher echelons of the command chain intervened to force Guderian to withdraw from Yelnya. Why?

The answer lies in the emerging strategic paralysis gripping the Germans. A strong block of officers (including Halder, Bock, and Guderian) had emerged which favored preparations for an immediate renewal of the offensive towards Moscow. They stood in opposition to Hitler, who was committed to detaching the Panzer Groups from Army Group Center, wheeling Hoth’s grouping northward to assist Army Group North in its drive for Leningrad, while Guderian cut south into Soviet Ukraine. The decision to hold the Yelnya Bridgehead, despite its exorbitant costs, constituted a mechanism for the “Moscow officers” to advance their schema by committing to the axis of attack towards the Soviet capital. Guderian, in particular, was highly skilled at insubordination and strongly opposed any diversion of his forces southward. Fuhrer Directive 33, issued on July 19, was the first document to explicitly instruct Panzer Group 2 to prepare to detach from Army Group Center to wheel south, but Bock and Guderian would for weeks treat this order as if it was subject to negotiation.

It was this debate which usually forms the basis of the “when did Germany lose the war” discussion. A very popular theory essentially argues that Halder and Guderian were correct, and that Hitler lost the war when he turned Guderian’s panzers south into Ukraine rather than continuing up the road towards Moscow. This theory is utterly incorrect, and we are left with the uncomfortable fact that Hitler was correct.

The basic issue was that the road to Moscow was not clear, and Army Group Center was in no position to continue its offensive at the beginning August. The basic reason for this was the arrival of a phalanx of Soviet reserve armies which would keep up relentless attacking pressure well into September, as the Red Army attempted a broad front counteroffensive around Smolensk. Although Army Group Center generally held (albeit by abandoning the bloody salient around Yelnya), the most important aspect of this offensive was that it kept Army Group Center locked in high intensity combat which prevented it from accumulating supplies or refitting for a renewed offensive. At this point, logistical connectivity to the army at the front was adequate to supply Army Group Center in the defense, but far too weak to allow supply dumps to be built up to support a new offensive. It was not until the Soviet offensive finally collapsed in September that Bock was able to sort his forces out to renew the attack.

Therefore, when officers like Guderian complain that the road to Moscow was “open”, and that they failed to take the city only because Hitler intervened, they are lying. In fact Army Group Center spent virtually all of August and early September defending itself, and was in no position to perform the requisite staging to resume the attack. Therefore, Hitler’s decision to divert Guderian to the south to encircle Soviet forces at Kiev was essentially correct. No offensive towards Moscow was possible in August 1941.

The problem, however, was that even where his strategic sensibilities were generally correct, Hitler exhibited indecision and paralysis which created a confused strategic direction. On August 4th he flew to Army Group Center’s headquarters at Borisov to meet with Bock, Hoth, and Guderian. All three generals echoed Halder’s arguments that the correct choice was to strike for Moscow as soon as possible. The meeting seemed to momentarily deepen Hitler’s indecision, and Guderian flew back to his own headquarters bent on preparing for a drive on Moscow.

Overall, the command conferences of early August strongly hint at the general shape of the German crisis. The field commanders - and Hitler, by extension - remained preoccupied with operational choice between an immediate offensive towards Moscow and diverting the panzers south to clear Soviet Ukraine. Little attention was given to the attrition of the panzer forces and the falling combat power of the army at the front. No credit was given to the Red Army, which had proven far more tenacious with vastly deeper reserves than expected. At this point, Germany still had substantial uncommitted panzer reserves - for example, the 2nd and 5th panzer divisions were still loitering in Germany - but no serious discussion was given to deploying them. The key question, in short, remained a matter of tinkering with the maneuver scheme, and Hitler’s indecision and failure to decide on a clear direction cost the Wehrmacht valuable time and resources.

How might it have been different? Here we come to the point of departure, which relies in the first place on Hitler exhibiting decisiveness and making his directives much more explicit. We also must assume that German field commanders, with their strong independent streak, actually follow orders. This is a tenuous assumption, but for the sake of our thought experiment it will have to do. Consider the following changes to the German operational schema:

On July 19, explicit orders are issued stipulating that the Yelnya Bridgehead was not to be pursued, with 10th and 17th Panzer Divisions rerouted north to link up with Hoth’s forces to seal the Smolensk encirclement.

Orders from Hitler make it clear that Guderian’s instructions are to prioritize sealing the Smolensk encirclement, followed by refitting preparations for a diversion south into Ukraine.

After the August 4-5th command conference, Hitler releases the panzer reserve to the eastern army. 2nd and 5th panzer divisions arrive to reinforce Army Group Center in September.

On August 11th, Guderian begins his strike south towards Kiev - note: in actuality, this order did not come down until August 25th due to Hitler’s indecision and the delays caused by Guderian’s failure to seal the Smolensk pocket.

Taken together with our decision to mobilize reserves and railway assets earlier (with the trigger being the discovery of unexpected Soviet field armies at Smolensk), this puts the Wehrmacht in a significantly stronger position. The attrition of Army Group Center would have been significantly lower in both relative and absolute terms, both because the severe losses suffered in the Yelnya salient would have been avoided, and due to faster and more comprehensive reduction of the Smolensk pocket. More decisive leadership would have also put the Wehrmacht two weeks ahead of its timetable, with the Kiev operation beginning on August 11th rather than the 25th.

This accelerated timetable is not hard to justify, and may in fact be conservative. As events actually played out, Guderian reported that his forces were staged for action on August 15th, but the order to turn south towards Kiev did not come until the 25th due to indecision in the high command. We can accelerate the operation even more by assuming a more rapid resolution to the Smolensk pocket (easily possible if Guderian had cared), and a faster rotation of the panzer units: as matters actually turned out, Guderian had great difficulty pulling his mechanized units out of the line due to the aggressive Soviet attacks on Yelnya. Defending further west in a less exposed position, he could have more quickly inserted infantry into the line to allow the panzers to refit and prepare to attack.

Settling in: Final Operations in 1941

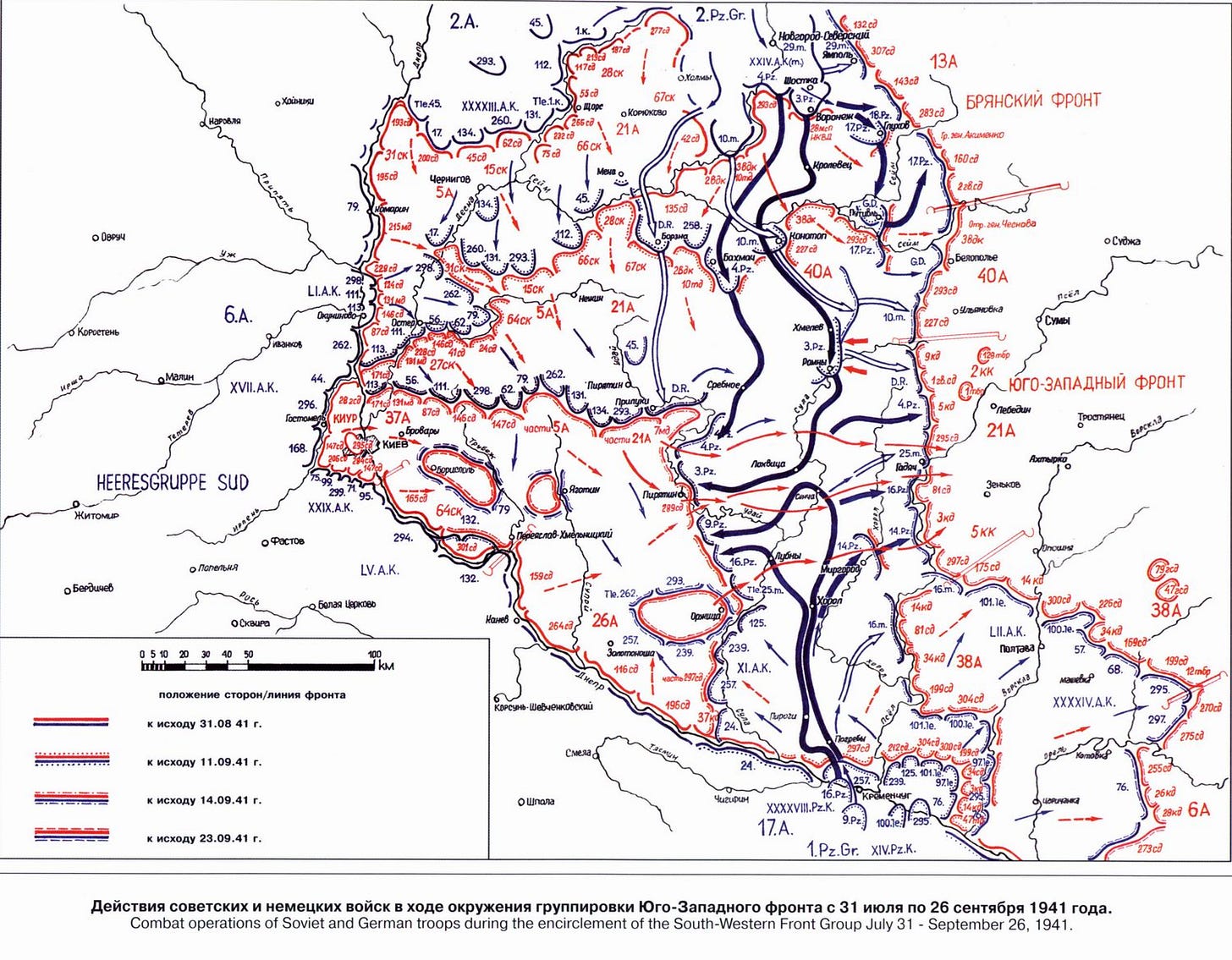

Thus far, we’ve elaborated a scenario where Army Group Center averted needless attrition, won a more complete victory at Smolensk, and wrapped up its operations there at least two weeks ahead of schedule. This would have in turn accelerated the German operation towards Kiev, which became perhaps the single largest German victory of the war. With Guderian’s panzer group slicing south into central Ukraine, the Wehrmacht encircled almost the entirety of the Red Army’s Southwestern Front, capturing some 650,000 Soviet troops in addition to hundreds of thousands killed and wounded. This was undoubtedly one of the great victories of the war, which wiped out a Soviet army group and overran critical economic regions. Hitler made many mistakes, but the diversion towards Kiev was not one of them.

So far, on balance, we have gained two weeks for the German timetable, modestly reduced the attrition of the panzer groups, and made an appropriate reaction to Red Army mobilization by beginning remediation of the manpower, material, and logistic crisis at the end of July, rather than waiting for the Soviet offensives in the winter. These are important changes, but how can they translate into a different outcome?

The fixation with Moscow tends to cloud the conversation. Arguably, the steps we have taken here increase the Wehrmacht’s odds of capturing Moscow by allowing Operation Typhoon to begin two weeks early. With the Battle of Kiev now concluding around September 10, rather than the 26th (as a domino effect of Guderian being able to move out early), theoretically Typhoon may have begun in mid-September, rather than on October 2nd, as it actually did. As events actually played out, Guderian began his movements northward on September 30th - but what would have happened if he had been two weeks ahead?

It’s easy to weave a cascading scenario. Perhaps, with an early launch to Typhoon, the Germans approach Moscow before Soviet reserves arrived, during the October panic. Perhaps 2nd SS Division Reich arrives at the Borodino crossroads before the Red Army’s 32nd Rifle Division (in real life, the Soviets won this race by a nose). Perhaps perhaps.

Or perhaps we are getting too far ahead of ourselves. Arguably, the limiting factor preventing Typhoon from launching earlier was not the need to wait for Guderian to clean up at Kiev, but rather the Soviet counteroffensive which raged well into September, preventing Army Group Center from building up a supply base for a fresh offensive. During the prolonged Soviet attack, the Germans continued to expend resources heavily on the defense, which precluded the necessary refitting and restocking for Typhoon. Even with Guderian two weeks ahead of schedule, the supply basis for Typhoon may not have accommodated an accelerated timetable.

Instead, we redirect much of Typhoon’s offensive punch. Rather than scrambling Guderian back to the north to participate in Typhoon, we keep 2nd Panzer Group in Ukraine to continue the drive eastward. Therefore, rather than belatedly deploying the panzer reserve to Army Group Center for a failed push toward Moscow, the panzer groupings of Army Group South (including Guderian’s group) are reinforced, and the primary German focus in September and October becomes the attainment of the Donets line and the midcourse of the Don, which can serve as defensive anchors for the winter. In actuality, German forces were able to reach Rostov, at the extremities of the Don and Donets confluence, in November, but were forced to withdraw due to Soviet counterattacks. With an accelerated timetable, the benefit of 2nd Panzer Group, and additional tank forces scrambling from Germany, our proposed line is in reach.

In our scenario, the offensive resources hoarded for Typhoon (including 2nd and 5th Panzer Divisions) are instead allocated to Army Group South, with our critical two weeks of lead time used to make a more forceful lunge for the Donets and the Don around Voronezh. Having attained this objective (which the Germans came close to reaching anyway, despite less time and far weaker forces), the Wehrmacht would be much better positioned for operations in 1942, holding both a much stronger defensive position, with much earlier mobilization allowing for replenishment of the armies over the winter, and stronger logistical connectivity.

Such a scheme would have accrued significant advantages for the Germans during the winter and the early months of 1942. The winter of 1941-42 was the first crisis of the Wehrmacht, when an overextended Army Group Center came under intense pressure from the Soviet winter offensive. It was during these months that the manpower shortages began to reach critical levels, with frontline strength falling as low as 2.5 million (from 3.3 million in September).

In our scenario, the more prudent decision to dig in Army Group Center’s front across the Smolensk-Bryansk corridor would have reduced the exorbitant losses of the winter. The Army Group would have been much better supplied in this position, far closer to its railheads and sheltered by river lines. This represents a further economization of manpower, in addition to the lesser attrition on the panzer units by better management at Smolensk and the decision to resist the fateful plunge through the mud towards Moscow. This, combined with our decision to release reservists from the labor force in the autumn and prioritize replacements for the eastern army would have had the Wehrmacht in a significantly stronger position entering 1942.

More importantly, keeping Guderian’s panzer group in Ukraine and directing combat power towards Rostov would have placed the Wehrmacht in an incomparably stronger position to launch the summer campaign of 1942. As events played out in reality, Germany’s lunge for the oil fields in 1942 began from a start line that was simply too far from the objective to be feasible. The Wehrmacht wasted the summer months simply clearing the Don bend, so that much of their fuel and time had frittered away before they were able to move into the Caucasus and the Volga bend. In our scenario, the start line for Case Blue is pushed forward significantly, so that the first half of the operation is no longer even necessary. Army Group South also begins in a much stronger position thanks to the decision to mobilize reserves in a more timely manner, rather than awaiting the winter crisis.

In our scenario, with the 1942 campaign starting from a much more advantageous scenario, the Wehrmacht actually has the oil fields within striking distance, and is able to lunge for the Caucasus in June 1942, rather than in the autumn. With less ground to cover, it is also within reason that the inner bend of the Volga could have been cleared in the opening phase of the operation, avoiding the disaster at Stalingrad. Germany gets the oil fields, and a fuel-starved Red Army is unable to take advantage of its growing motorization. This is a different world indeed.

Summary: Alternate History

What I’ve endeavored to show here is a twofold argument about Operation Barbarossa. First, it is certainly true that the Germans had options that could have put them in a much stronger position entering 1942, with both a more favorable line and significantly stronger forces. Secondly, the common argument that Germany’s mistake was delaying the attack on Moscow is incorrect.

After the Battle of Smolensk, it is simply not true that the road to Moscow was “open” in any sense. An echelon of newly deployed Soviet field armies attacked Army Group Center relentlessly for weeks, and the expense of warding off this Soviet offensive prevented Bock’s army group from accumulating the supplies and material needed to renew the offensive. It did not much matter what Guderian did in August 1941, because the Soviet counteroffensive sapped the German momentum.

However, German mistakes during the Battle of Smolensk strained their timetable and caused wasteful attrition of the panzer groups. Guderian’s insistence on holding the Yelnya bridgehead prevented the timely sealing and reduction of the pocket at Smolensk. Army Group Center wasted time and combat power at Smolensk. However, Guderian held the Yelnya bridgehead because he falsely believed that Smolensk would be followed up by a rapid thrust for Moscow, despite the fact that Hitler was leaning firmly towards a diversion to the south. There is blame enough to go around. Guderian was insubordinate on many occasions and erred greatly in his decision to grab and hold Yelnya, but Hitler by the same token failed to provide decisive leadership during those critical weeks, and did not clearly articulate the strategic roadmap.

We have demonstrated, however, that better battle management at Smolensk would have gained the Wehrmacht valuable time and reduced the attrition of keystone units. Furthermore, Germany had reservoirs of manpower and logistical resources that it failed to mobilize until the winter crisis had reached its most dire. This too caused the eastern army to be much weaker than it needed to be. Solving these problems would have required decisive leadership from Hitler in moments of growing strategic confusion, and this was not forthcoming.

We can therefore outline the following amendments to German conduct of the war in 1941:

Germany initiates escalated mobilization on July 21st in response to the discovery of fresh Soviet armies around Smolensk. This includes immediate measures to mobilize reservists, rationalize economic management, curtain civilian economy production, transfer prisoners of war to industrial work, and deploy railway assets to the east. We would argue that the appearance of a new Soviet echelon at Smolensk presents a rational moment where German leadership could have discarded their flawed assumptions about Soviet collapse and manpower availability and begun intensified mobilization which, in reality, did not begin until 1942-43. This results in 750,000 additional personnel deployed to the eastern army and 50% higher railway capacity by the autumn.

Germany adopts a more rational personnel policy which places the eastern army in a place of absolute priority, curtailing Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine access to new personnel. This frees up at least 250,000 additional personnel for the army.

During the opening stages at Smolensk, Hitler issues explicit orders that Guderian abandon the drive for the Yelnya bridgehead and link up with 3rd Panzer Group to fully seal and reduce the Red Army grouping at Smolensk. The strategic trajectory is laid out unequivocally: there is no immanent drive on Moscow; priority is resolving the encirclement at Smolensk to free up Panzer Group 2 to wheel south towards Kiev.

Guderian now begins the encirclement at Kiev two weeks ahead of schedule and with greater strength (due to avoiding losses at Yelnya.) After clearing the Kiev Encirclement, Guderian remains attached to Army Group South, which is further reinforced with 2nd and 5th Panzer Divisions.

The now-heavily reinforced Army Group South drives for the Donets and the midcourse of the Don, with the critical autumn objectives being the capture of Voronezh and Rostov.

The Wehrmacht would begin 1942 with both greater strength, more time, and a shorter distance to go in order to reach the Caucasus and the oil fields, achieving the only “war winning” blow that was actually possible against an enemy like the Soviet Union.

These suggestions illustrate two things. First, it is obvious that Germany’s margin of error was razor thin, in that even relatively small miscues promised to spiral the strategic situation out of control like so many dominoes toppling into each other. The fact that it is tenuous to sketch a path to victory, even in hindsight, suggests that the likelihood of finding the path in real time was slim indeed. However, we should remember that even with all their missteps, the Wehrmacht miraculously found itself within tantalizing reach of victory again and again. In 1941, they made it to the suburbs of Moscow, and in 1942 they came within two kilometers of the oil fields at Ordzhonikidze. History is often a near run thing.

This was wildly entertaining. Thank you Serge. And, of course, if the Nazis hadn't been so murderously bloodthirsty to their Slavic neighbors but came as liberators from Soviet communism, how many would have welcomed them. But, like the scorpion such depravity was simply "in their nature."

Wondering if you saw the comedic piece in today's WSJ by Bernard-Henri Lévy who argues "Drone Attack Shows Why Ukraine Will Win This War." I found your sober analyses a worthy antidote to this sort of idiotic cheerleading of the legacy media and wonder at your response.

Thanks Serge -- very well written, argued, and supported -- and a nice take (in a short document) on a very complex and controversial topic. Furthermore, I found your comments about the nature of the USSR's pre-invasion demands regarding Finland, Bulgaria, and the Turkish straits to be new information to me -- I had not heard those precise arguments before, so thank you for those tidbits as well.

Before, commenting on your thesis of your paper, let me recap your arguments (very briefly and in reverse order as you presented them):

1) Key operational mistakes were made during the battle of Smolensk (mainly by Guderian)

2) These mistakes were amplified by disagreements in the German high command, a culture of 'insubordination' amongst certain German generals in key positions of power at the time (e.g. the Moscow-focused group), and limits on Hitlers direct and timely 'control' or the eastern war effort (e.g. he was not as 'in control' operationally as Stalin was for the USSR)

3) These decision-making mistakes were amplified further by absolutely atrociously incorrect German intelligence assessments of Soviet actions, capabilities, and future potential (e.g. the 20 fold mischaracterization of Soviet force generation capabilities)

4) These intelligence shortfalls affected German government policies on mobilization, prioritization and logistics -- which dramatically reduced the effective force the German's could deploy in the east in 1941 and 1942

5) These policy decisions were driven by the political desire to minimize the cost to the German 'home front' and avoid any chance of discontent or future 'domestic collapse' from Germany as in WW1

6) These policies (and the resulting 'short preventive war' strategy) were conducted based on perceptions of current Soviet weakness, longer term Soviet threat, and current / future German economic vassalage to the USSR.

Overall, these are great points and well made (it's a pity that you don't have more time and space to elaborate more on these topics and add to them as well -- but perhaps you will in a book some day).

I would make two comments, however, that I hope help you (and your readers). The first is that, as you point out, even with changes at Smolensk and better force generation and logistics for the Germans in late 1941 to 1942, it is not clear that enough troops, supplies, logistics, would get to the right front lines 'to make a difference' in mid 1942. More material would likely get through to German lines (and attrition through combat would likely have been marginally better), as you point out, but 'more' is not necessarily the same as 'enough'. The logistic mess through the main railroad trunk lines from Germany to the east was terrible but getting those supplies out to the downstream feeder lines and then the last 20 miles to the troops in the front line positions may still have been even more difficult and maybe insurmountable in 1941. It is entirely possible that by cleaning up the bottleneck in one place of the supply chain the German's would have merely move the bottleneck to another part of the chain further down the line -- and that downstream part was even less amenable to fixing from the 'corporate center' on short notice than the railroads, depots, and logistic centers were. So, while it is possible that Germany in mid 1942 could have been better positioned in the war (if it made better choices in mid to late 1941) -- it's not clear that it actually would have been substantially better off than it was historically (it all comes down to what the real bottlenecks of supply were at the time in theatre). In other words, operationally, your contention that moving south to Ukraine (versus towards Moscow) is sound -- but if the logistics were really unfixable in 1941, it might not have made much of a difference what was undertaken operationally at that point.

The second comment is on your summary of Germany's pre-invasion economic vassalage to the USSR. Your points on that topic are very correct -- although you can (and probably should) take that point even further than you do. Germany in the 1930's (and hence in the 1940's) was always one step away from economic collapse -- and that economic collapse was repeatedly kept at bay by the next big desperate economic (or political or military) gamble. Looking more deeply into the economic antecedents of the political / military decisions of the German high command might further flesh out your thinking on this overall economic / military overlap.

For example, Germany's move to massive government spending in the time period of 1933-1937 was, in some sense, Keynesianism, which stimulated economic activity (autobahns, employment schemes, public work projects, social welfare spending, defense rearmament and mobilization) via debt (e.g. the MEFO bonds) and expenditure of its foreign exchange reserves. Whether the short term internal economic 'boom' of these policies was worth the 'economic cost' (in terms of debt and nationalization of the economy) is one issue -- but one thing for sure was that this debt and foreign exchange fulled binge allowed for was the importation of needed raw material (oil, rubber, minerals, food) necessary for the economic and military activity.

By 1937, Germany's growth (and given its debt, even its present economic statistics quo) was 'at the end of its rope' -- it had exhausted its foreign exchange reserves and future imports of raw material was about to stop (or the internal economy and military build-up would have to be drastically reversed). The annexation of Austria and the seizure of its gold reserves forestalled this problem. Similarly, the annexation of Czechoslavackia did the same in 1938 (and the seizing of Polish assets in 1939 did as well -- as did the capture of Norwegian, Danish, Dutch, French, Belgian assets, etc). Each military escalation by Germany in this pre-war and early war years was necessitated, in some ways, by its general economic 'vassalage' (just as you suggest was the case in 1941 between Germany and the USSR). It needed resources (and in the short term, foreign exchange assets) and it relied on those assets to continue its war effort without a full war economy (e.g. to support trade with Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Sweden, Italy, and the USSR). So, in that sense, the German preventive war rationale had precedent given its recent past.

Furthermore, this 'economic' element of the war also helps explain why it was essential (or at least thought to be essential) for the German high command to keep war mobilization as 'limited' as possible (e.g. not fully mobilizing the people and economy for war). The 'future Germany' that these leaders wanted in terms of economics 'needed' certain economic conditions (like limited manpower mobilization, some amount of a civilian consumer economy, adequate civilian food / medicine / fuel access, reasonable rates of inflation, etc.) to survive and prosper longer term. Therefore the German political command was trying to strike a 'balance' between war and future post-war economic survival: mobilize too far and too early and the 'peace' that would be won would be 'lost'. versus not mobilize enough or too late and risk losing the war and the peace. It was a difficult top-level war planning conundrum -- and one that they hesitated on too long (in hindsight). However, the game plan of 'risking economic ruin' and 'saving everything' with a 'successful roll of the brinkmanship or military dice' was totally consistent with how they had managed events in the previous decade (so it is no surprise that they tried that yet again in 1941).

Thanks for the article and the opportunity to comment.