“It is impossible to hold an olive branch in one hand and fire a pistol with the other.”

So quipped Wilhelm Solf, a diplomat with the Imperial German Foreign Ministry. As Europe groped its way through the mass casualties and civilizational exhaustion of the First World War, Solf was one of the few key personnel in the German government to advocate for a negotiated peace in early 1917, as the war crossed its halfway mark. Of course, we know that World War One did not end in 1917 - attempts to negotiate a settlement collapsed almost instantly, with the allies rejecting German proposals outright. Strangely, one of the main points of discontent did not even relate to war aims or the particular terms of peace, but rather to the issue of blame. Both the Central Powers and the Allied Entente were adamant that the other side ought to formally accept the blame for the war, and talks never really progressed farther than that.

The abortive peace process was further muddled by the intervention of US President Woodrow Wilson. Riding the confidence won by his victory in the 1916 election, Wilson felt that he had political freedom of action to intervene more actively in Europe, and the United States - perhaps alone among all the powers of the world - seemed to have levers of influence over both parties in the conflict. Wilson’s agenda, as such, was to negotiate a “peace without victory”, with neither side annihilating the other, in the spirit of comity and mutual respect. A harsh victory’s peace, according to Wilson, would be felt as a humiliation by the defeated party, and breed the conditions for future war by seeding intractable resentment and revanchism.

Knowing what we know about the Treaty of Versailles, which was just this sort of deeply resented punitive peace, Wilson’s comments seem prescient. Unfortunately, the idealistic (some would say naïve) American President had failed to read the room. His Peace Without Victory speech was well received by the domestic American audience, but rejected as anathema by virtually everyone else, including not only the Germans but also the Anglo-French Entente.

Wilson, aloof across the ocean, failed to understand two very important things. First, that Europe’s blood was up after years of carnage. This was particularly the case after Germany’s botched attempt to extend peace feelers to the allies; the Entente was outraged at what they saw as insulting German terms, while the Germans in turn were in a defiant mood after the Entente’s abrupt rejection of those same terms. Secondly, Wilson failed to grasp that he was not viewed as an impartial mediator, particularly by the Germans. While he may have viewed himself as a statesman with a gifted touch, uniquely positioned to halt the bloodshed, Berlin fundamentally did not trust him or the allies, and preferred instead to ruthlessly exploit all its kinetic powers. Peace Without Victory may sound charitable and cozy, but victory was much more appealing. After millions of casualties, all parties preferred to go for the win rather than limping away with a draw.

At the risk of forcing the analogy too bluntly, we find ourselves with a very similar situation in Ukraine. President Trump, like Wilson, came off the high of his election victory fully determined to insinuate himself into the war as a peacemaker. His commitment to ending the war, like Wilson’s speech of January 22, 1917, played very well with his domestic audience, but resonated little across the Atlantic. Like the Germans a century ago, Russia does not see the American President as an honest broker, and he has discovered that his leverage is not so great as he thought. More importantly, it is as true now as it was in 1917 that it is damnably difficult to convince warring states to stand down when their blood is up, and to walk away from the sunk cost of so much bloodshed. The motif of blame has even made its return, with many European parties writing off the idea of concessions to Russia simply on the basis that Moscow is the guilty party in this war.

We have a First World War problem, and it will resolve itself with a First World War solution, when one warring party succeeds in exhausting and breaking the other. As Ukrainian and Russian negotiating teams met in Istanbul for their brief token negotiations, which were predictably non-productive, the two parties continued to exchange strikes in the usual ratios, and the Russian Army ground forward along the line of contact. Wilhelm Solf’s olive branch was never seriously in play, but the pistol remains operational. Blood is up in Ukraine, and it will continue to soak the ground.

The Collapse of Diplomacy (Again)

The recent Istanbul “peace talks” between Ukraine and Russia began and ended in the blink of an eye, making it obvious (as if it were not already) that nothing productive could come from the discussion. The second round of talks, which took place on June 2nd, lasted for about an hour, which is scarcely enough time for diplomatic niceties. Predictably, nothing was agreed upon except for a tentative deal to exchange POWs and a KIA remains swap, which has already begun to come off the rails.

The problem with diplomacy right now is that there is little appetite to actually negotiate a deal, but all three major parties (Ukraine, Russia, and the United States) are willing to engage in performative diplomacy with objectives that are orthogonal to each other. It is unlikely that any of the negotiating teams actually arrived in Istanbul with an expectation or intention of ending the war, but they did have genuine objectives that they were trying to achieve. The issue is further obfuscated by the ancillary issue of the mineral rights deal between Ukraine and the United States, which is not directly related to the prospects for a negotiated peace, but is nonetheless an aspect of President Trump’s performative negotiating.

For Russia, the purpose of performative diplomacy is to publicly reiterate its war aims and assert confidence in its battlefield dominance. It is critical to remember that at every stage of this war, when given the opportunity, Moscow has restated the same fundamental terms, which constitute the Russian “bottom line”: these include the withdrawal of Ukrainian forces from the four annexed oblasts, recognition of Russian annexations, limits on the size and armaments of the Ukrainian armed forces, a ban on Ukrainian membership in military alliances, including NATO, Russian protection as an official language of Ukraine, and the lifting of international sanctions on Russia.

This amounts, in concrete terms, to Ukrainian surrender. Moscow has been hesitant to use language like this, and has certainly avoided bombastic World War style language like “unconditional surrender”, nevertheless this is what these terms represent. This is particularly the case when it comes to those cities in the annexed oblasts that are still under Ukrainian control - Kherson, Zaporizhia, Slovyansk, and Kramatorsk. Ukrainian possession of these cities remains the most important card in Kiev’s hand, and indeed the only real leverage that they have vis a vis Russia is their ability (for the time being) to force the Russian Army to sustain additional casualties to take these cities. Once Russia has those cities, Ukraine has nothing to offer in negotiations. Russian reiteration of these war aims, then, amounts to a demand that Ukraine hand over its most important negotiating assets, which is equivalent to surrender.

We should therefore understand Russia’s actions in Istanbul as an ostentatious display of force, making a thinly veiled demand for Ukrainian surrender in an act of performative diplomacy. This performance is directed squarely at Kiev and Washington.

Ukraine, however, is engaged in its own form of performative diplomacy, but the Russians are not Kiev’s intended audience. Rather, Ukraine “negotiates” as a form of signaling towards Washington (and to a lesser extent Europe). This is seen in the fact that, while Russia is demanding de facto Ukrainian surrender, Kiev is asking for stopgap measures like limited ceasefires. The goal, for Ukraine, is not to end the war, but to paint the Russians as the intransigent party, unwilling to even agree on a temporary ceasefire. As the Ukrainians see it, this creates a win-win scenario: if Russia does agree to a ceasefire, this blunts Russian momentum on the battlefield and provides an opportunity for the AFU to recalibrate; if Russia does not agree, this can be presented to the west as proof of Russian bloodthirstiness.

The result, then is, that Moscow and Kiev are approaching the question of negotiations with incompatible paradigms. Kiev, ideally, would like a ceasefire without any negotiated obligations; Moscow wants negotiations without a ceasefire. Russia has demonstrated that it is perfectly comfortable negotiating while military operations are ongoing. If the discussion collapses, it can always be resumed later, and in any case the Russian Army can continue advancing. This flexibility comes from Russian confidence that it will achieve the same strategic objectives in either case. For Ukraine, on the other hand, negotiating against a backdrop of ongoing combat is bad math, because it is the AFU that is steadily being rolled back and seeing its strategic position weaken.

Taking this to its paradigmatic conclusion, Russia and Ukraine have fundamentally different views of the relationship between military operations and negotiation. Ukraine seeks to negotiate to improve its military position: using performative diplomacy to leverage additional support from its western backers, and seeking a ceasefire to reconstitute its forces. Russia, on the other hand, uses military operations to improve its position in negotiations. The particular war aims and demands of the two parties are almost inconsequential, as the two sides do not even agree on what negotiations are for.

Meanwhile, the United States is engaged in its own equally performative form of diplomacy, which is aimed at giving Trump strategic flexibility in Ukraine. By arranging negotiations between Russia and Ukraine (and delivering Moscow his own labyrinthian peace plan), Trump can argue that he made a good faith effort to end the conflict. If it works, and a negotiated peace can be reached, he will be hailed as a great peacemaker. If it does not work, he is well positioned to wash his hands of Ukraine by passing Kiev off to the Europeans. We already see the signs of this, with Washington threatening to walk away from the peace process, preparing to wind down military assistance to Kiev, and Trump adopting increasingly apathetic language towards Ukraine.

Trump is no doubt eager to avoid turning Ukraine into his own Afghanistan, and he has the benefit of a junior partner (Europe) which is perfectly willing, if not fully able, to hold the bag for him. All in all, Trump has managed Ukraine fairly well, if one understands that his chief objective has been to gain political flexibility, rather than ending the war at all costs or achieving some sort of Ukrainian victory. Simply by getting Ukrainian and Russian negotiators into the same room (no matter how performative the proceedings), he’s gained the leeway to tell the American public that he gave it his best shot; when the negotiations collapse, he can begin washing his hands of Ukraine and hand the flaming bag to the Europeans.

With the rapid and predictably unfruitful talks in Istanbul now over, it looks like we are finally ready to move past the charade - particularly given the latest news that the US is cancelling unrelated bilateral discussions with Moscow. The thing that stands out the most from all of this, of course, is that virtually nothing has changed in the relative negotiatory stances. Notwithstanding Vice President Vance’s assertion that Russia is “asking too much”, Moscow is making exactly the same demands that it has been making for years, and it is running into the same brick wall.

Neither Trump’s election, nor the failure of Ukraine’s offensives on the Zaporizhian steppe and Kursk, nor the ongoing Russian progress clearing the Donbas has had any material effect on the negotiating calculus. These things all mattered in their own right, but curiously none of them have moved the needle on diplomatic prospects in Ukraine. The negotiations are a strangely static, sterile, performative enterprise, serving mainly as forums to allow Ukraine and Russia to publicly reiterate their aims and complaints. In that respect, they are mostly harmless. Meanwhile, the war will be fought to its conclusion.

Ukraine’s Blockbuster: The Strike War in Context

By far the biggest headliner moment of the year, at least in western media, was Ukraine’s unexpected attack on Russian strategic aviation assets at dispersed airbases deep within Russia itself. The attack, codenamed Operation Spider’s Web, was certainly notable for three distinct reasons. First, it degraded Russia’s strategic aviation (strategic bombers and Airborne Early Warning and Control), which are assets that had been essentially unscathed to this point. Secondly, the strike affected Russian bases as far afield as the Russian Far East, which damages the sense of Russian geographic standoff and the inviolability of the country’s vast dimensions. Third and finally, the platform for the attack was highly novel, with the Ukrainians launching small drones from truck-carried launchers which were assembled within Russia itself, at a covert Ukrainian base in Chelyabinsk.

One item which is interesting to note off the top is that, although the use of such a truck-mounted launching system is new, the idea itself is not, and in fact originated with the Russians themselves. More than a decade ago, Russia began playing with a system, affectionately dubbed “Club K”, which purported to fire cruise missiles from a launch platform which appeared in all respects to be an innocuous shipping container. Originally marketed as an anti-ship weapon, Club K drew scathing reviews as an exercise in perfidy, and China’s ongoing work on the theme has received similar criticism.

This, of course, makes it rather funny that Ukraine has received such widespread acclaim and unqualified praise for Operation Spider’s Web. The complaints levied against Russian and Chinese experiments with Club K type systems are essentially that it is unlawful to disguise strike systems as innocuous civilian cargo. Clearly, the Ukrainian strike is not particularly different, and merely swaps a shipborne cargo container for a truck. Now, those who have been reading my work for some time no that I am not the type to wring my hands about “international law”, which I view as an essentially nonsensical concept. International Law is not really law, but only an institutionalized mechanism for the strong to constrain the weak. Nor, for that matter, does hypocrisy really matter. What matters, and particularly in war time, is not what a state is “allowed” to do by international law, but what it is able to do, and what sort of risk appetite it has. In the case of Club K and the Spider’s Web, we see that their perfidy is our audacious covert operation. The hypocrisy does not really matter, but it is at least a little funny.

So, on to the damage from Spider’s Web itself. Initially, much of the Ukrainian infosphere was bandying numbers that were patently absurd, claiming that something like 70% of Russia’s strategic bombing fleet had been destroyed. The official claim from the Ukrainian government was that 40 bombers and early warning aircraft had been badly damaged or destroyed, which would amount to perhaps a third of the Russian inventory. A review of the video published by Ukraine, as well as satellite imagery, confirms around a dozen total losses, and western defense officials have landed on the number 20, including six destroyed TU-95s and four TU-22s.

Putting this in context, it means that Russia lost approximately 12% of its TU-95 fleet and 7% of its TU-22s, with the inventory of TU-160’s escaping unscathed. All told, that is approximately 8.5% of Russia’s strategic bombers. The issue, which constantly emerges on the Ukrainian side, are absurdly high expectations and a gross misunderstanding of what “success” means. In any realistic paradigm, destroying nearly 10% of Russian strategic bombing assets with relatively cheap drones would be viewed as a considerable success, but the ongoing expectation that Russian capabilities can simply be wiped out prevents such a realistic assessment.

We should acknowledge that the upsides here for Ukraine, lest we fall into the trap of “coping.” It’s manifestly obvious that Spider’s Web was both a schematically ingenious and technically innovative operation on the part of Ukraine. Striking at five widely separated Russian airbases with assets staged deep in the Russian heartland, Spider’s Web was both bold and ambitious, and it did not require risking particularly valuable Ukrainian assets. From a risk-reward calculation, this was clearly a success for Ukraine.

Furthermore, it must be plainly admitted that the destroyed Russian aircraft are, in fact, mostly irreplaceable. The TU-95 has been out of production for years, and the extant fleet was expected to serve a workhorse role for the foreseeable future. Russia has some production of the TU-160, with perhaps four aircraft scheduled for delivery in the near term, but this will obviously not fully replace the recent losses. Still, things could have been much worse. Losses were minimized by the total failure of strikes on two of the five target airfields. At Dyagilevo airfield near Ryazan, Russian air defenses were effective and no aircraft were hit; meanwhile, the attack on Ukrainka airfield in Amur Oblast failed when the launch container blew up. It also appears that the strike on Ivanovo Severny hit a pair of A-50 (AEWAC) aircraft but did destroy them.

We’re left with something of a mixed bag. Ukraine demonstrated a novel and ambitious ability to strike Russian assets and did destroy several irreplaceable aircraft, but the results were certainly far short of what Kiev was hoping for. The Russians have good reason to feel that they escaped the worst of it. Certainly, this will be an inducement to accelerate the construction of hardened aircraft shelters, which has been underway at a plodding pace, though obviously not at all airfields, since 2023. Thus far, the Russians have mainly prioritized hardening airfields in range of conventional Ukrainian strike systems (in places like Kursk and Crimea). Spider’s Web will likely prompt similar hardening at far flung airfields that were once thought to be relatively safe.

Add it all up, and the ledger on Spider’s Web is fairly straightforward: it was a significant success for Ukraine, in that it destroyed a good number of valuable Russian assets while risking very little. However, multiple Russian airfields escaped without losing aircraft, thanks to a mix of successful Russian air defense and Ukrainian malfunction. The Ukrainians are left with a success, but one that was much smaller than they might have hoped for.

More significantly, however, Spider’s Web degrades Russian capabilities in a way that is very unlikely to make a material impact for Ukraine itself. Losing strategic bombers, especially models that are out of production, puts more stress on the remaining airframes and pinches capacity, but these losses are highly unlikely to make anything except the most marginal reductions in Russian strikes against Ukraine.

The first and most basic reason for this, of course, is that the air-launched missiles of the strategic bombing fleet form a relatively small fraction of the munitions that Russia fires into Ukraine. The vast majority have been, and continue to be, drones (like the venerable Geran) and the ground launched Iskander. Gerans, in particular, form the most numerous munition now in use, with hundreds launched per day amid rapidly increasing production. TU-95 participation in airstrikes is a relatively scarce occasion, and no matter how loud and cinematic the Big Bears may be, they are not remotely the primary launch platform in this war.

In fact, Spider’s Web provides an opportunity to pontificate on an ancillary point of considerable importance. Russia’s use of air launched cruise missiles has slackened significantly in 2025, as they stockpile missiles not only for use in Ukraine but also for other contingencies. In fact, mere days before Spider’s Web struck at the strategic bombing force, Ukrainian media was wondering aloud about the relatively scarce Russian use of these systems, noting that air launches by strategic bombers had occurred only a handful of times this year. At the moment, the key factor constraining Russian cruise missile strikes on Ukraine is neither a shortage of missiles nor a lack of airframes, but strategic decisions to stockpile assets.

In the grand scheme of things, the loss of irreplaceable bombers does compress top-line Russian capabilities, but not in a way that changes the calculus for Ukraine right now. Destroying a grouping of TU-95s on the ground is a success for Ukraine, particularly given the cheap assets that they expended for the task, but it does not address the problem, which is that Russia has established the ability to sustainably bombard Ukraine, particularly with Iskanders and Gerans, all while stockpiling strike assets. It is possible that, in the wake of Spider’s Web, Russia is compelled to make more frequent use of the TU-160 (which has been used extremely sparingly to this point), but it is clear that Russia has many strike options and its capabilities vis a vis Ukraine remain more than adequate. This is a war of industrial attrition, and Ukraine’s covert operations are not a substitute for the capacity to wage a persistent air campaign.

Ultimately, this brings us to the broader point. Spider’s Web was an innovative example of an asymmetric operation, but this merely speaks to the presence of a broader asymmetry in this war, as such. Russia is the far richer and more powerful fighter in this conflict, which paradoxically means that it has more assets both to use and to lose. Ukraine managed to destroy nearly a dozen Russian strategic bombers, but Ukraine has no strategic bombers at all. Russia will always be vulnerable to asymmetric losses of this sort, because it possesses assets that Ukraine does not. Losing strategic bombers is not good, but it’s better than not having them at all. In this conflict, there’s still only one party that has a vast and diverse arsenal of indigenously produced strike systems, and one party that has to resort to (admittedly very clever) truck launched drone attacks due to the exhaustion of its conventional strike capabilities.

Hitting the Seam: Donbas Front Update

On the ground, the primary axis of effort for the Russian Army continues to be the central Donbas front, around the cities of Kostyantynivka and Pokrovsk. This is particularly the case now that the two axes in South Donetsk and Kursk have been largely scratched off. A brief look at the situation map reveals a swelling Russian offensive in this critical central sector. The past few years ought to have given us a good sense of caution about using words like “breakthrough” and “collapse”, so I will instead simply argue that the Ukrainian Army is in serious trouble in this sector.

The reasons are fairly straightforward, and lie not only in the escalating manpower shortages facing Ukrainian formations, but also in a triple vulnerability that exists in this particular sector of front. In short, the Pokrovsk-Kostyantynivka axis suffers from what we will call a “triple seam” which makes it operationally very vulnerable, and the current Russian offensive is aimed directly at this seam, or operational joint. Let’s elaborate.

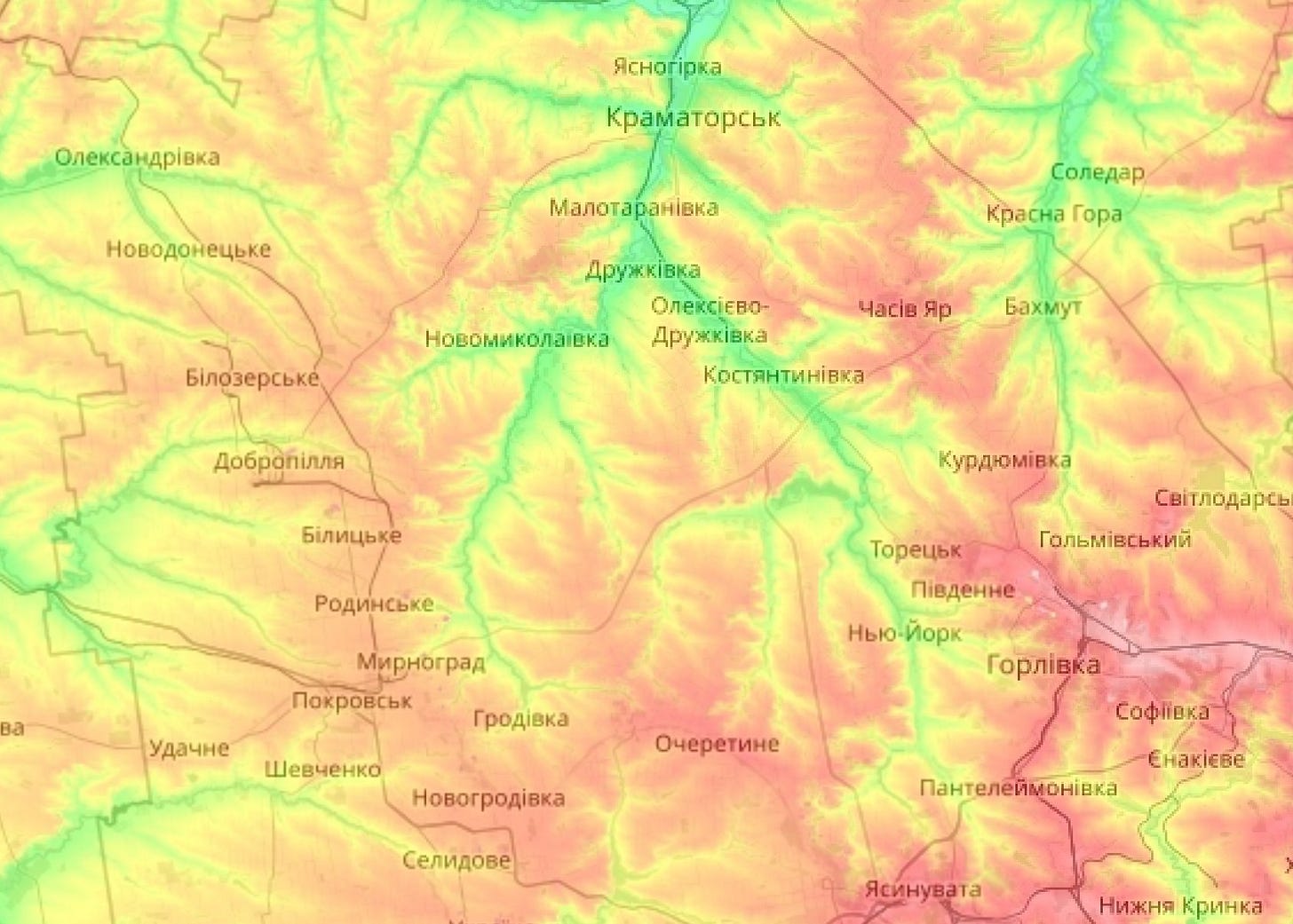

The first seam, or vulnerability, is geographic and thus by far the easiest to understand. The basic issue is that the urban belt in western Donetsk (running from Kostyantynivka up to Slovyansk) lies on the floor of a valley. In the Kostyantynivka sector in particular, there are local high points around Chasiv Yar, Toretsk, and Ocheretyne, all of which are now firmly in Russian hands and form the bases of support for advances towards Kostyantynivka. To the west of Kostyantynivka, there is a wedge-shaped plateau which separates the city from Pokrovsk, and it is into this elevated wedge that the Russians are now advancing.

The operational problem for Ukraine, however, goes much farther than the elevation map. In fact, the elevation issue dovetails with structural problems with Ukraine’s prepared defenses. To understand this, we must first remember the state of the front in 2023. Two summers ago, the main axis of Russian effort was through Bakhmut - that is, an advance due west across central Donetsk. At that point, the southeastern axis of the front (Avdiivka, Krasnogorivka, Ugledar) was holding steady for the AFU. Facing the prospect of a Russian advance directly from the east, the Ukrainians built up defenses around Kostyantynivka which face eastward, towards Bakhmut.

The collapse of the southern front creates a pivot in the Ukrainian defenses, so that the axis of the Russian advance is now from the southwest of Kostyantynivka, rather than from the east. Although the Ukrainians began building new defenses (oriented towards the south) after the collapse of the southern front, there remains a significant gap west of Kostyantynivka. Furthermore, the “joint” where Ukraine’s defenses intersect is essentially at the southwestern limit of Kostyantynivka itself.

Recent Russian advances have now put them behind the Ukrainian positions guarding the southwestern approach to Kostyantynivka. When the Russians reached Yablunivka (approximately June 4), they were firmly in the rear of the defensive belt southwest of Kostyantynivka, opening up the Ukrainian line here for entry into the city’s western flank and link up with the advance out of Toretsk.

Given Ukraine’s lack of manpower, these trench systems threaten to become highways for Russian forces, as we saw along the Ocheretyne axis in 2024. Once Russian forces break into these belts, they are able to roll along the length of the belts deep into Ukrainian space.

In short, a variety of structural weaknesses are all dovetailing in the same sector of front. The Russians are advancing from advantageous high ground into structural seams in the Ukrainian defenses, precisely into the area of front that wedges Pokrovsk and Kostyantynivka apart from each other. The result is an emerging double envelopment, with the Russians plowing through the middle towards the rear areas behind these cities. The terrain and the orientation of the Ukrainian lines have accommodated an enormous Russian splitting wedge which will sever the lines of communication to both cities. This would be a major problem under ideal circumstances, but given Ukraine’s inability to properly man its positions, it has become a crisis.

In the coming weeks, Russian forces will continue their expansion into the interstitial space between Pokrovsk and Kostyantynivka, probing their way into Ukraine’s operational liver. When they reach the space just to the southwest of Druzhivka, they will be positioned to cut the lines of communication into both cities. Simultaneously, they will continue the rollup of the defenses on Kostyantynivka’s southwestern flank. With Russian forces penetrating into the city’s southwestern flank, the city is already in an untenable position,

Of the two cities, Kostyantynivka is likely to fall first, with the Russians beginning to assault the city proper at some point in July. In what I would characterize simply as a command decision, the Russians have been patient about pushing Myrnograd and crumpling the shoulder of the Pokrovsk position. At this point, they seem unlikely to do so until the advance into the seam has compromised the lines of supply from the rear.

At the risk of being somewhat hyperbolic, this remains the only sector worth watching closely. Russian forces are exerting relatively minimal efforts on other axes of the front. There is incremental progress, pregnant with opportunity, around Lyman, and Kupyansk, and the expansion of the Russian “buffer zone” in Sumy oblast bears watching. It seems extremely unlikely, however, that Russia has intentions in the near term of pushing the front towards the city of Sumy itself; rather, the buffer zone is aimed at seizing a forward defensive line along the high ground on Ukraine’s side of the border, keeping an advantageous front open to dissipate Ukraine resources. The center of gravity in this war remains the central Donbas, and the key operational fact, as such, has been the pivot in the Russian strategic axis. After advancing westward through Bakhmut in 2023, they broke open the south in 2024 and are now advancing orthogonally into the Ukrainian defense between Pokrovsk and Kostyantynivka, in the penultimate act of the Donbas campaign before they reach the prize in Kramatorsk and Slovyansk.

Conclusion: Strategic Clarity

I have written frequently about the critical importance of a “theory of victory” when waging a war. This refers, in the simplest sense, to the need for a state to have an overarching concept for leveraging power into its war aims. This is the strategic ligament which connects military operations and diplomacy to the state’s wartime objectives.

As the war moves on into its fourth year, Ukraine and her western backers have cycled through several different theories of victory which were quietly discarded after coming apart at the seams. In the first year of the war, the theory of Ukrainian victory centered on created an unacceptable cost-benefit calculus for Russia. If Ukraine and the west showed unexpected resolve, keeping the AFU fighting fiercely in the field, it was hoped that Russia would back down from fighting a long war, particularly as sanctions gnawed away at the Russian economy. Instead, Russia began mobilizing for a longer fight, and the Russian economy has thus far weathered the sanctions intact.

This theory of victory was then replaced with a model predicated purely on military operations, which supposed that a decisive victory could be won in the south by knifing through Russian defenses in the land bridge. This theory came apart in a much more visible fashion, with western armor burning on the steppe after a botched attempt to breach the Surovikin line. A second attempt to restart decisive operations met a similar end in Kursk.

In the last year or so, the theory of Ukrainian victory pivoted once again, particularly under the auspices of the new Trump administration, in favor of words like “attrition” and “stalemate” as a mechanism to gain a negotiated settlement. If the front in Ukraine can be locked into something approximating a stalemate - that is, if the cost of further advances can be made prohibitively high for Russia - the conditions will be set for a negotiated peace.

In contrast, Russia has had an essentially consistent theory of victory since late 2022, when it began mobilization. That theory is very simple: by establishing a basis for sustainable military operations against Ukraine, consistent pressure and ground advances can be maintained until either Ukrainian resistance collapses or Russia controls the Donbas. To this point, Ukraine has not demonstrated capabilities - either to go on the offensive or to halt the Russian advance in the Donbas - that change this basic calculus.

Commentators in the west rarely try to view the conflict from Russia’s perspective, but if they could they would quickly see why Russian confidence remains high. As Russia sees it, they have absorbed and defeated Ukraine’s two best punches on the ground (the 2023 counteroffensive and the Kursk operation), and they have weathered a long and steady infusion of western combat power without the trajectory of either the ground campaign or the strike war fundamentally shifting. Meanwhile, Russia has essentially scratched off the entire southern Donbas, pushing the front across the border into Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, and they are poised to wrap up the central sector of front as the advance around Pokrovsk and Kostyantynivka blooms.

We’re left, then, with a jarring disconnect. On the one hand, the Trump Administration approached Ukraine as if their election fundamentally changed everything and instantly raised the probability of a negotiated peace. Russia, however, rather rightly feels that nothing has changed at all. They have absorbed everything the west has thrown into the conflict, and they continue to both advance on the ground and relentlessly strike Ukraine on a material basis that they clearly view as sustainable, without unduly burdening civilian life in Russia.

If anyone was surprised, then, that Russia came to Istanbul only to reiterate the same terms they’ve been presenting from the beginning, they were clearly not paying attention. Russia has no inducement to soften its stance so long as it feels that the battlefield calculus is unchanged, and nothing that the west (or Ukraine) has done since 2022 has given Moscow a valid reason to revise its views. Russia’s baseline demands ought to be well understood by now, as is Russian willingness to achieve those aims kinetically. If Ukraine will not give up the Donbas at the table in Istanbul, it can be taken by the Russian Army. In the end, there’s very little difference.

We are left with Woodrow Wilson’s formulation. Not, of course, his high minded “peace without victory”, which is a nonstarter today just as it was in 1917. Rather, we’re left with the hardened and embittered Wilson of 1918. With the United States now an active belligerent in the conflict, Wilson’s outlook had darkened immensely, and he now categorically opposed negotiating with an undefeated Germany at all. He had concluded instead that “If Germany was beaten, she would accept any terms. If she was not beaten, he [Wilson] did not wish to make terms with her.”

If the olive branch has wilted, the pistol will do.

Thank you for a quality report devoid of any propaganda. A good read.

Trump lied, he scammed me on ending Kiev’s war.

Trump scammed the Iranians, using IAEI spies, and the fig leaf of a deal his saboteurs did to Iranian generals what they did to rusting bombers.

No one will talk to US and the EU is run by even less rational policy than US.

NY I rush who worked the docks were surveilled by the 1915 version of MI 6 thinking the U.S. branch of Irish resistance would harm US arms going to London.

US was on the Brit side outside a few Irish .