Author’s Note: In response to a query I received from several people, and for clarification’s sake, all battle diagrams, maps, and schematics in this series are by me unless explicitly noted otherwise.

In the opening entries of our study of battlefield maneuver, we looked at two diametrically opposed maneuver concepts and how, despite being opposite ideas, both can lead to victory when implemented correctly. In the first entry, we looked at the concentration of fighting power in a single attacking mass, and in the second we looked at the dispersal of fighting power into independently maneuvering bodies.

The fact that two completely antithetical force deployment schemes can both lead to stunning victory speaks to the intensely unpredictable nature of battle - there is no single formula or recipe for success, as everything ultimately depends on both the fighting qualities of the armies involved and the reaction of the enemy force. In both of our previous entries, we examined victories that could have very easily become catastrophes if the enemy had reacted more effectively. If the British had launched a concentrated armored counterattack on Rommel while he was withdrawn in the cauldron, for example, or if the Austrian army had moved decisively against the Prussian 2nd Army at the onset of war, then Gazala and Konnigratz would not have been exemplary victories.

In our third entry in this series, let us shift gears a bit, and instead of examining a particular maneuver pattern, contemplate the idealized goal of fluid battle - a goal which can be achieved a variety of ways. This goal is the battle of annihilation - a condition which occurs when the enemy is so operationally compromised that the entire enemy army is destroyed as a cohesive unit capable of giving battle.

In archaic warfare, annihilation battles were relatively rare, simply because armies were slower moving, command and control was unsophisticated, and battles tended to be fought in a linear manner - set piece affairs with opposing armies dutifully lining up opposite each other on a nice big field. In these conditions, and with most of the army moving at a modest marching pace, true encirclement was difficult.

Nevertheless, the era of pre-gunpowder set piece battles does offer a few idealized examples of annihilation battle - where these battles did occur, they offer ideal archetypes for the maneuvers in question, because archaic battles were fought in a relatively small and defined space, making it relatively easy to map and understand the movements involved (unlike, say, the German invasion of Poland, which took place across many hundreds of square miles with arrows pointing every which way). Even more significantly, these battles represent the idealized form of warfare as such, and embody the elysian vision of battle: to destroy the entire enemy army in one brilliant encounter, in one day, on one field. No general can aim for anything higher.

Hannibal’s Prototype

The Carthaginian general Hannibal Barca is a historical character of some ambiguity for many. He is perhaps best known for crossing the Alps with war elephants - certainly a cinematic and stunning achievement, but devoid of context for most people. The elephants, while certainly the element of the story which stands out the most (and looks best in paintings) in the end were a fairly minor tactical footnote.

Notwithstanding the oddity of war elephants in the snows of the Alps, Hannibal’s audacious march represented an attempted solution to a rather classic military problem.

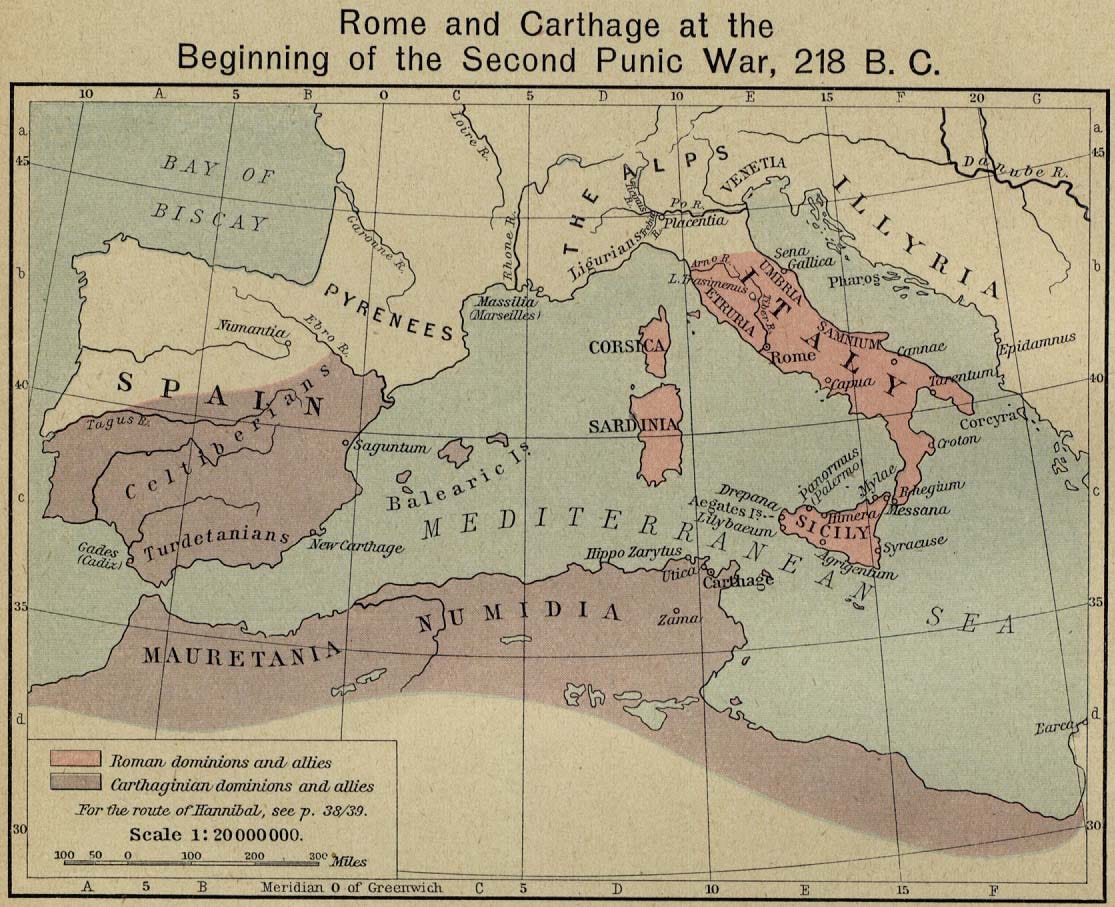

Carthage had already suffered a costly defeat at Roman hands, only a few decades previously in the First Punic War (the first of three) which cost Carthage its position on the strategically crucial island of Sicily. In that war, Rome demonstrated extensive powers of military force generation - building enormous fleets, and sustaining large military forces in action across a wide theater. When war broke out again (this time over Carthaginian expansion in Spain encroaching on Roman interests), Hannibal faced the classic conundrum of planning for a war against an enemy with superior powers of force generation and sustainment. This was a strategic quandary that any Prussian or Mongol planner would have been familiar with.

Hannibal’s operational solution was fairly simple - he would march his army over the Alps and invade Italy directly from an overland route. This would not only eliminate Roman naval power from the equation, but also threaten to shake Roman control over satellites and allies in the Italian peninsula. Even more importantly, from a military perspective, bringing the war directly to Rome’s doorstep would make it possible to force decisive battle.

In the spring of 217 BC, Hannibal and his army burst out into Italy and began stomping about in Etruria, burning and breaking things with impunity. Rome, shrewdly understanding that it was not good to allow the Carthaginians to smash up their core territories, quickly wheeled an army under the command of one Gaius Flaminius to pursue Hannibal and come to grips with his army. The ensuing battle would become a one-sided affair of a sort which to this day has never been replicated.

Flaminius and his legions caught up with Hannibal on June 20 near Lake Trasimene (today Lake Trasimeno). The scene presented a perfectly idyllic Italian lakeside: a charming line of rolling hills lay just to the north of the lake, and the main road wound along the narrow stretch of flat ground between the shore and the hills. It was here on the road that Hannibal pitched his camp, in full view of the pursuing Romans. Flaminius, seeing Hannibal stop in such a visible spot along the shore, presumed that the Carthaginians would offer battle the next day, and pitched his own camp just up the road, intending to close the distance and initiate combat the following morning (the 21st).

Hannibal did intend to fight a battle the next day, but not in the way Flaminius expected. That night, as the Romans rested snugly in their camp, Hannibal dispatched his forces on a march in the dark to form up on the transverse side of the hills, where they could not be seen from the road. A night march was a tricky enterprise in the ancient world, especially when torches were prohibited for fear of giving away their movements, and especially when the army is moving off road, but the Carthaginians managed to get cleanly into position. The following morning, when the Romans came marching up the road in column formation towards Hannibal’s camp, they had absolutely no notion that the mass of the Carthaginian force was directly on their left, just over the crest of the hills.

When Hannibal sprang his ambush, the outcome of the battle was a forgone conclusion. A Roman army in a marching column would take hours to deploy into battle formation even under ideal circumstances, and the situation at Lake Trasimene was far from ideal. The Carthaginian strike was preceded with a sequence of trumpet blasts ordering the attack. The Romans could hear these trumpets blowing behind them, but could not see their enemy yet, leading to general confusion which metastasized into full on panic when Hannibal’s army crested the hills and began to rush at their flank. Pinned against the lake, the Romans could not form even a rudimentary battle formation and soon collapsed into isolated groups of men desperately trying to organize themselves.

Most of the Roman army was cut down or surrendered right there against the lake - those that managed to escape and flee were run down by Hannibal’s pursuit and met the same fate. Flaminius’s army - some 25,000 men in all - was completely liquidated. The Greek historian Polybius - a key contemporary source - claimed that 15,000 Romans were killed and entire remainder was taken captive, marking the total annihilation of the army. Against this horrific toll, the Carthaginians could weigh less than 2,000 casualties of their own.

The Battle of Lake Trasimene was truly unique. It probably marks the earliest definitively documented battle of encirclement and annihilation, where the enemy force is not just badly mauled, but wiped out in its entirety after being cut off from all avenues of retreat. What is more, the battle remains to this day the only known example of complete operational ambush. Traps and ambushes of various kinds have been utilized throughout the ages, but at Trasimene Hannibal became the first and only commander to successfully ambush the enemy with the entire main body of his army.

A small detachment of cavalry scouts could have spared Rome the catastrophe, but Flaminius could not be bothered to do any reconnaissance whatsoever. After all, he could see Hannibal’s camp in front of him - he thought, therefore, that he knew exactly where the Carthaginians were. A stunning moment of carelessness and hubris which cost him his own life and the lives of 25,000 legionaries.

Trasimene was a singular military achievement. Modern surveillance and reconnaissance technology has relegated the possibility of total operational ambush to the annals of history. Unless mankind regresses back to a more primitive state, Hannibal’s gambit on the lakeshore will never be replicated. It will remain a unique example of clever planning and calculated risk taking - and it was, to be sure, a risk. Hannibal deliberately dispersed his army off road in the dark with a large Roman force loitering only a few miles away. A risky maneuver, to be sure, but skillfully executed for stunning results.

The annihilation of a formidable Roman army in a single afternoon serves as the prototype for an idealized form of battle - whether we call it encirclement, double envelopment, or, in the Prussian idiom, “Kesselschlacht” or Cauldron Battle - we know it when we see it: the enemy force is swallowed whole and destroyed.

As for Hannibal, his campaign of annihilation was just getting started.

Hannibal’s Masterpiece

The loss of an entire army along with its commander right in the heart of Italy naturally raised alarm in Rome. The immediate political fallout was the election of one Quintus Fabius Maximus to the post of Dictator (still holding its original meaning of a specially appointed magistrate endowed with emergency powers).

Fabius had a shrewd grasp of the strategic situation. As he saw it, Hannibal was a formidable foe, but operating far from home with no reliable access to supply or reinforcement. Time, therefore, was on Rome’s side. Fabius conceived of a campaign of asymmetrical attrition - avoiding pitched battle with Hannibal, but harassing his foraging and scouting parties, waging a guerilla war of resource denial while Rome rebuilt its legions.

The strategy was probably sound from a military perspective, but it was politically poisonous in the context of Rome’s hyper-belligerent and masculine political system, which demanded direct confrontation and the ostentatious smashing of enemies. The so called “Fabian tactics” were roundly denounced, most famously by Fabius’s political rival Marcus Minucius Rufus, who is recorded by Livy lambasting the dictator in front of the army:

“Are we come here as to a spectacle, that we may gratify our eyes with the slaughter of our friends and the burning of their homes? If nothing else can awaken us to a sense of shame, do we feel none when we behold these fellow citizens of ours whom our fathers sent as colonists to Sinuessa to secure this frontier from the Samnite enemy? It is not our Samnite neighbours who are wasting it now, but Phoenician invaders, who have been suffered to come all this way, from the farthest, limits of the world, by our delays and slothfulness.

Predictably, Fabius’s emergency powers were not renewed by the Senate, and the decision was made to pursue a more direct course of action. This suited Hannibal perfectly - he had spent the better part of a year moving around Apulia with Fabius declining to offer him battle. Determined to force the Romans to meet him in a set piece battle, Hannibal seized the citadel of Cannae in Apulia. This was a valuable asset, as it served as the supply depot that housed much of the grain harvested in the region. The grain was nice, of course, but the real purpose was to force the Romans to give battle.

The ploy worked. The loss of a key supply hub, after a year of frustrating avoidance under Fabius, provoked an outcry in Rome, and the Senate resolved to muster an unprecedently large army to dislodge and destroy Hannibal once and for all. Polybius wrote:

The Senate determined to bring eight legions into the field, which had never been done at Rome before, each legion consisting of five thousand men besides allies… Most of their wars are decided by one Consul and two legions, with their quota of allies; and they rarely employ all four at one time and on service. But on this occasion, so great was the alarm and terror of what would happen, they resolved to bring not only four but eight legions into the field.

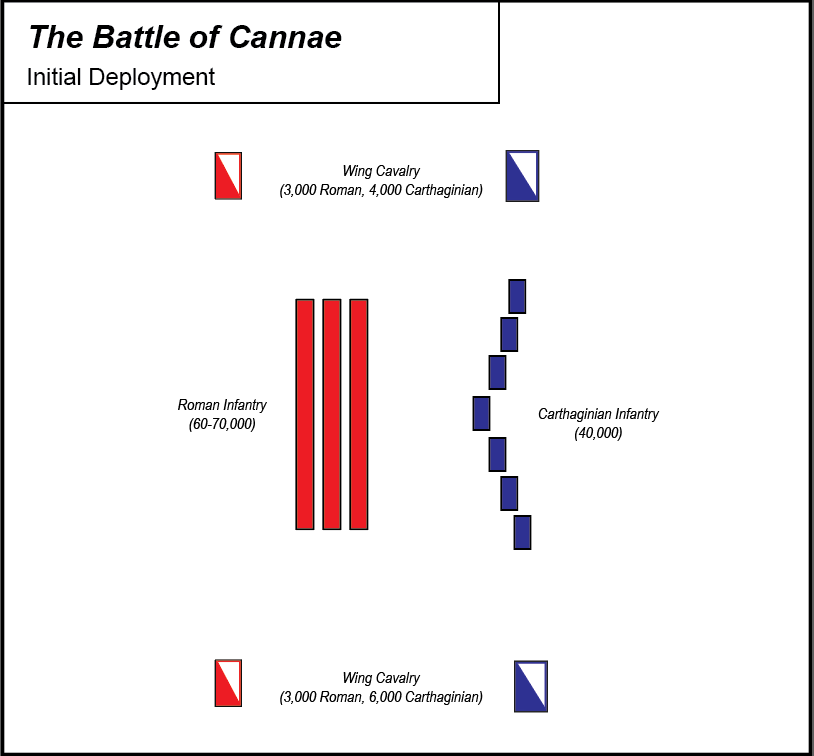

The army that Rome brought to Cannae was indeed massive. The core of the army was some 40,000 legionaries, augmented with a roughly equivalent number of allied troops contributed by Rome’s subsidiary Italian city states. Ancient troop counts are always tricky, but a force of roughly 80,000 is considered credible, of whom perhaps 6,000 were cavalry. Hannibal’s army was markedly smaller - on the order of 50,000 men. Notably, however, the Carthaginian cavalry probably numbered close to 10,000, giving Hannibal a decisive edge in this crucial arm, even if his infantry were woefully outnumbered.

Hannibal not only faced a foreboding numerical disadvantage, he also had to contend with the organizational and troop quality issues that were idiosyncratic of Carthaginian armies. Carthage was a polyglot mercantile empire whose core Phoenician metropolis represented only a tiny fraction of the population. Accordingly, Hannibal’s army was a diverse assembly of mercenaries, allies, and subcontractors - Gauls, Numidians, Lybians, Iberians, and more. These were competent troops whose commanders had strong personal attachment with Hannibal, but commanding and deploying a variegated force like this was intrinsically harder than wielding the more coherent Roman-Italian mass.

Notwithstanding the long odds, Hannibal would annihilate the Roman army.

The initial deployment of the armies did not suggest that anything particularly wild was coming. The Romans arrayed in a straightforward formation, with their infantry massed up in the center and their 6,000 cavalry split into roughly equal forces on the wings. Hannibal’s infantry formed a slight wedge formation which was slightly wider than Rome’s central mass, but significantly more shallow and fragile. The most noteworthy aspect of the deployment was the fact that Hannibal’s cavalry, which already outnumbered the Romans, was unevenly distributed, with a full 6,000 horsemen placed on Hannibal’s left flank under the command of his brother Hasdrubal.

Hannibal’s entire concept revolved around the cavalry arm being his single point of strength. He could be reasonably sure that his cavalry, which were both more numerous and qualitatively much better, would rout Rome’s own cavalry - the question then was how to A) leverage this fact, and B) survive the onslaught of the Roman infantry mass while the cavalry battle unfolded on the wings.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.