Author’s Note: I decided to take the paywall down on this one so people can get a feeling for the flavor of the series and decide whether they want to subscribe or not.

Military practitioners and thinkers have long recognized that battle is a unique enterprise subject to its own bizarre dynamics and logic. Indeed, the logic of battle frequently seems to be intrinsically paradoxical. The great historian of strategy, Edward Luttwak, favors the simple example of an army choosing between two roads to advance towards an objective - one paved and direct, the other circuitous and muddy. As Luttwak puts it, “only in the paradoxical realm of strategy would the choice arise at all, because it is only in war that a bad road can be good precisely because it is bad.” The benefit of taking the bad road, of course, may lie in the fact that the enemy is unlikely to expect it, thus allowing the advancing force to circumvent the enemy’s defenses.

Let us begin at the beginning. Everybody dreads when authors define their terms, but I think in this case it is truly apropos. Let us define Battle as follows: organized groups of men deploying armed force against each other for the purpose of destroying the other’s ability to offer armed resistance. This purpose, of course, can be achieved by killing the enemy, capturing them, driving them from the field, or breaking their ability to resist by destroying their will to fight.

When we say “organized groups of men”, we mean this in only the crudest sense of differentiating friend from foe. No doubt, the most archaic battles, fought as mankind first climbed out of hunter gatherer life into the first forms of political organization, consisted of little more than loosely organized mobs - but the political form, the identification of “us” and “them” with some political issue at stake, is what makes a battle a battle, rather than crude, animalistic violence.

The crudest and most basic form of battle would consist of two groups of men of equal size and armed with equivalent weaponry hacking at each other in a disorganized melee. This sort of scene is instructive - imagining this as the most primitive form of battle, we can see that neither side holds any advantage or leverage. The outcome of the battle would simply be the compounded result of numerous close order fights between similarly armed men, fighting one on one. Writ large, the result of such a battle would be almost entirely up to chance - the leader has nothing to do but pray for the best.

Clausewitz believed that battle was an interaction between three dynamic forces: violent emotion (fear of death, hatred of the enemy, and bloodlust), rational calculation and planning, and pure chance and randomness. Our hypothetical primitive battle - the disorganized melee - is one where the influence of rational calculation is nonexistent. The victor will be decided entirely by chance and the interplay between the fear, hatred, and courage of the warriors.

Military history, as such, is the story of men attempting to control battle by maximizing the influence of rational calculation and minimizing the influence of violent emotion and chance.

The way that military practitioners achieve this is by developing and exploiting what we will call battlefield asymmetries, which are the source of advantage. An asymmetry can be technological - one army possesses a new form of weaponry that the other does not - or it can be numerical, either in the number of men or their firepower. An asymmetry can be geographic - perhaps one side has better access to water, food, or fuel - or it can be derived by modifying the battlefield with defensive constructs.

In this series, we will examine how armies generate asymmetries with maneuver.

Maneuver is the organized and intentional movement of large units for the purpose of intentionally creating an asymmetry on the battlefield. These asymmetries, and the advantages that they produce, ultimately lie in the way that maneuver warfare turns the maneuvering force into the proactive combatant, dictating the tempo and focal point of the battle, and forcing the enemy to become reactive.

Colonel John Boyd (whom we mentioned in the previous entry) identified the key benefit of maneuver in the disruption of the enemy’s “OODA Loop”. The OODA Loop (Observe, Orient, Decide, Act) is a typical bit of techno-bureaucratic jargon, in that it is simply an overly complicated way of saying “decision making”. Maneuver aims to frustrate the enemy’s decision making by creating unexpected situations on the battlefield, which force him to become reactive. Ideally, creative maneuver places the enemy on the back foot for the remainder of the battle, leaving him trapped in a cycle of constant reaction to the maneuvering force’s proactive movements, rather than initiating proactive action of his own.

Maneuver warfare is generally viewed as the opposite of attritional warfare. Attritional battle aims to steadily degrade the enemy’s fighting power with the protracted and steady application of superior force; maneuver warfare aims to quickly destroy the enemy’s fighting power by gaining and exploiting a battlefield asymmetry. While the advantage of maneuver seems obvious - by seeking a decisive engagement, maneuver offers the chance at a quick and decisive victory - it also threatens the possibility of a quick and decisive defeat.

Accordingly, maneuver warfare is traditionally associated with armies that face a clear disadvantage in attrition warfare - smaller armies with weaker material or logistic capability. Facing an unfavorable asymmetry in a conventional, attritional battle, they seek to trade this for a positive asymmetry through maneuver. This form of warfare is most strongly associated with the Prussians.

Terminology of Maneuver

Prussia lived with a constant, unpleasant reality: they were at a significant disadvantage in any conceivable war against any peer great power. Prussia’s weakness was comprehensive - both geographic (the country was wedged in the middle of the continent without natural defensive barriers) and demographic (her population was by far the smallest of the great powers). Therefore, any Prussian ruler had to come to grips with the undeniable fact that they would inevitably lose, and likely lose spectacularly, in any sort of protracted war. This is what we call an asymmetry.

To compensate for her negative asymmetries, Prussia inculcated an approach to warfare that could create positive asymmetries on the battlefield. This style of warfare, in German, was called Bewegungskrieg - literally “movement war”. This stood in contrast to Stellungskrieg - “position war”, or attritional combat. With her smaller population and vulnerable borders, Prussia would lose a positional war and therefore had no choice but to fight a movement war.

Now, the Prussians (and later the Germans) are certainly not the only practitioners of maneuver warfare, nor even the best. However, they were the first military establishment to think deeply about maneuver as a science, and therefore much of their terminology has become standard. The writings of Clausewitz furthermore helped to standardize the use of the Prussian maneuver lexicon.

Two terms in particular are important for us here. The first is the German word “Schwerpunkt” – literally “focal point”. This referred to the concentration of the army’s fighting power on the battlefield at a decisive point, rather than distributing it evenly. The goal of warfare, in Prussian thinking, was fairly simple: identify a point in the enemy’s formation that is both vital and weakly defended, maneuver the schwerpunkt of the army to that point, and immediately attack before the enemy can respond.

Antoine-Henri Jomini - the famous Swiss military theorist whom we discussed in a previous entry - summarized it pithily. In his mind, the “fundamental principle of war” is “to operate with the greatest mass of our forces, a combined effort, upon a decisive point.”

Another commentator, far less known but perhaps even more interesting, came to similar conclusions. Emil Schalk is an enigma - virtually nothing is known about him except that, during the US Civil War, he was living in Philadelphia where he wrote multiple books, including analyses of the war and a lively volume titled “Summary of the Art of War - Written expressly for and dedicated to the United States Volunteer Army.” He also, rather uniquely, submitted multiple newspaper columns commenting on the operational conduct of the Civil War (which in turn provoked complaints by other readers that he was too generous in praising Robert E Lee’s generalship). This otherwise mysterious man was, we must conclude, the first military blogger. No picture of him is known to exist, but I feel him to be a kindred spirit.

In any case, Schalk summarized maneuver principles as follows:

There are three great maxims common to the whole science of war; they are:

1st—Concentrate your force, and act with the whole of it on one part only of the enemy’s force.

2nd—Act against the weakest part of your enemy—his center, if he is dispersed; his flank or rear, if concentrated. Act against his communications without endangering your own.

3rd—Whatever you do, as soon as you have made your plan, and taken the decision to act upon it, act with the utmost speed, so that you may obtain your object before the enemy suspects what you are about.

In other words, create a schwerpunkt and throw it as quickly as you can against the enemy’s vital point of relative weakness. Any Prussian theorist would have approved.

Creating a schwerpunkt, or force concentration, has the obvious advantage of producing an asymmetry at the decisive point itself - but it also creates negative asymmetries elsewhere in the battlespace, because the concentration of force at the schwerpunkt necessarily entails denuding the forces around the rest of the space. As we will see later, when the effort of the schwerpunkt fails, the entire battlespace can collapse.

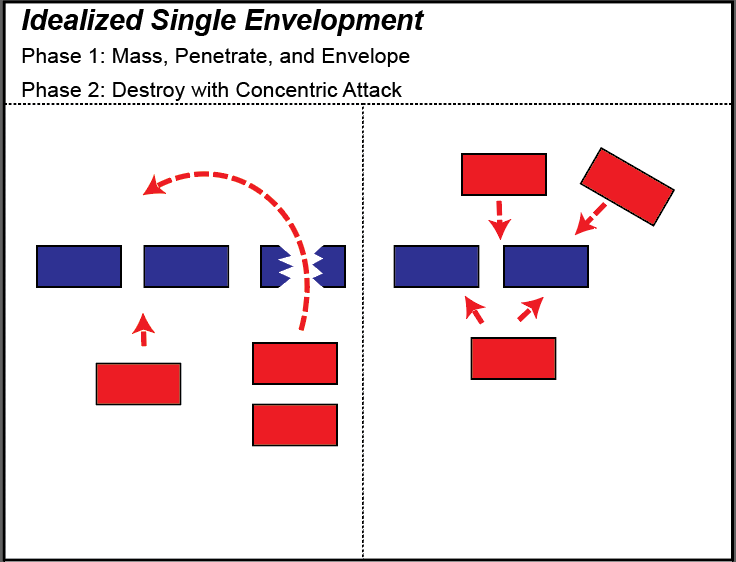

The second key bit of terminology that we can borrow from the Prussians is the notion of concentric attacks. This refers to one of the key objectives of maneuver warfare. Concentric attack simply means partial or full envelopment of enemy units so that they can be attacked from multiple directions. Clausewitz, in his trademark aphoristic style, simply noted that forces facing concentric attack “suffer more, and get disordered.” On an operational level, concentric attack cuts off forces from lines of resupply, and on a tactical level it is extremely difficult for a force to defend itself from multiple lines of attack. The most important benefit, however, is that by obstructing lines of retreat, it becomes possible for the maneuvering force to attempt an annihilation battle, which occurs when the opposing force is not merely attrited, but liquidated en-masse either through surrender or outright destruction, because an enveloped force cannot simply withdraw when the calculus is no longer in its favor.

This is the framework of warfare idealized by the Prussians: rapid and decisive movement of large units to envelop the enemy and destroy his fighting force with concentric attacks. In the Prussian parlance, this allows wars to be “short and lively”, decided in a single definitive battle rather than slowly ground out over time. While Prussian descriptive terminology remains popular, they were not the inventors of this approach to warfare - merely the first to describe it with a widely used lexicon. The schwerpunkt, it turns out, is very ancient indeed.

Smashing Sparta

Few ancient warriors have amassed such an enduring and widely known legacy as the Spartans. From the cinematic reimagining (complete with Gerard Butler’s glistening, potentially computer generated abs), to the science fiction super soldiers of the Halo series, to the use of the word Spartan itself as a synonym for arduous and ascetic ruggedness – Spartans are, for many, the archetypical warrior. Most with at least a cursory knowledge of ancient history know the Spartans by acclaim to be the best warriors of all the Greeks.

It is true that the Spartans fielded notably competent and powerful armies. This, of course, had less to do with some sort of genetic predisposition for combat, and more to do with the structure of Spartan society. In the classical era, most Greek city-states fielded citizen armies – quite literally the adult male population under arms, with farmers and craftsman mobilizing into a militia. In contrast, Spartan society was decidedly more martial, even in peacetime. Sparta had a large workforce of slaves (helots) who comprised the majority of the population – Herodotus claimed that there were something like seven helots for each Spartan. The presence of such a large, servile labor force enabled Spartan men to participate in rigorous military-social institutions, including regular training in arms and a military academy for young men. So while the average Athenian soldier was likely to be a farmer who grabbed the family shield, spear, and helmet when he was called up, a Spartan was more like a professional soldier who had helots to do the farming for him.

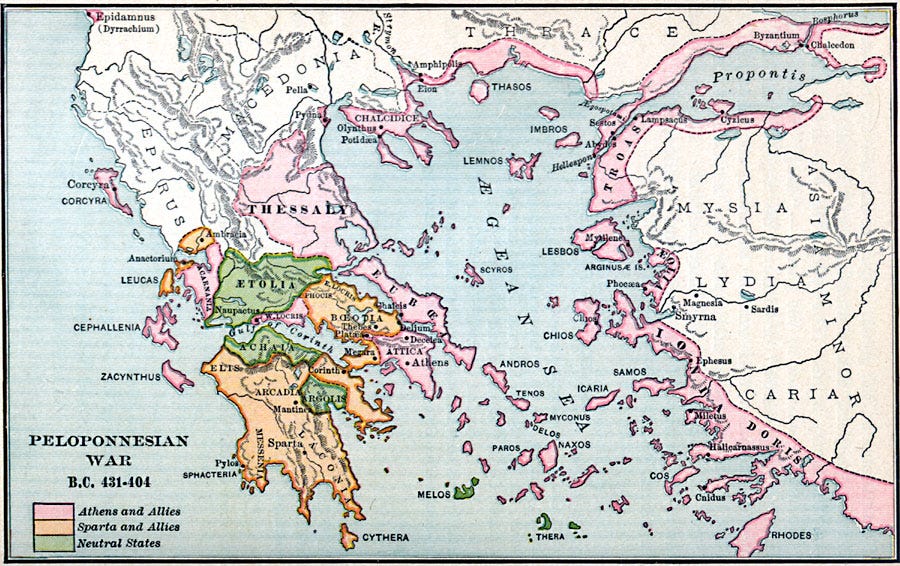

Sparta’s peculiar social structure and martial institutions bore their intended fruit. From roughly 431 to 404 BC, the Spartans fought a protracted conflict with Athens (the Peloponnesian War) which shattered Athenian preeminence in southern Greece and established Sparta as the dominant Greek power. This struggle witnessed many decisive Spartan victories, including the famous Battle of Syracuse, which saw an Athenian army entirely crushed by Sparta and her proxies.

The Battle of Leuctra brought a sudden, unexpected, and spectacular end to the era of Spartan hegemony.

Athens and Sparta are by far the two best known ancient Greek city states – Athens for its philosophers and Sparta for its warriors. Far less famous is Thebes – the third city of Greece. Yet it was this same uncelebrated Thebes that won a decisive victory against the Spartans, despite being heavily outnumbered, crushing the Spartan army and breaking its power. In 371 BC, Thebes and Sparta found themselves at war (the minutia of Boetian and Peloponnese politics being fairly uninteresting here), and the Spartans managed to take the Thebans by surprise with a quick advance into the environs of Central Greece, offering the Theban army battle near the village of Leuctra.

The Theban commanders were at first divided over whether to even chance a pitched battle with the Spartans in such conditions. The Spartans outnumbered them, probably something like 10,000 to 7,000, and they were after all Spartans. A Theban general named Epaminondas argued vociferously to take the battle, and in the end got his wish.

Greek warriors were almost exclusively outfitted as heavy infantry called hoplites (after their equipment, which were called hoplon). The trademark kit of the hoplite was a large shield and a spear, perhaps 8 to 14 feet long. Hollywood movies generally don’t do the best job representing historically accurate combat of any kind, but few warrior types have been as badly portrayed as the hoplite. Movies almost always incorrectly portray hoplites hefting monstrously heavy metal shields. Greek shields were instead usually made of wood. If the warrior was wealthy, it might be rimmed or even covered with bronze, but this was not common. Counterintuitively, the favored shield woods tended to be low density and soft, like willow. This not only made the shield lighter than a heavy material like oak (or, God forbid, metal), but soft woods tend to dent when struck, rather than splinter.

Furthermore, the actual dynamics of hoplite combat tend to be distorted, partially because we do not have a precise picture of how it functioned. The hoplite shield gave preferential protection to one side of the warrior. This fact gave rise to the compact formations that are characteristic of Greek battle depictions - though historians endlessly quibble over how these formations were developed. Did an enterprising Greek commander conceive of the phalanx and implement it from above? Or was it the result of natural self preservation instinct of the men? A hoplite holding his shield in his left hand would intuitively crowd closer to his right hand neighbor to protect his exposed side. Did subconscious crowding over time lead to the mass adoption of the phalanx as a standard method? We may never know.

The other critical question which remains unanswerable is what happened when hoplite masses met with each other. Some historians insist that the phalanxes actually crashed into each other - two blocks of men, all carrying 30 kg of armor and equipment, smashing into each other at a combined speed of ten miles per hour. Others counter that a full speed collision would have caused a terrible disorder, and the armies likely slowed down as they reached the contact point. Then there remains the question of how well, exactly, these masses of men were able to maintain formation as they jogged at each other - did the spacing remain tight, or drift slightly apart? All these issues are debated endlessly by classicists, and each expert insists that he knows with absolute certainty how archaic battle functioned.

We can, however, make a few definitive statements.

Hoplite warfare at the time was maniacally focused on what we might call “battlefield continuity.” This manifested in two primary concerns. First and foremost was properly balancing the width and depth of the line: too little depth, and the enemy could break through; too little width, and the enemy could outflank you. The second concern was ensuring that the line advanced fluidly and cohesively, with a consistent pace, so that one end did not get ahead of the other, thus compromising the structure of the formation. This seems to have been a constant preoccupation. The legendary Athenian general and historian, Thucydides, wrote in his History of the Peloponnesian War:

It is true of all armies that, when they are moving into action, the right wing tends to get unduly extended and each side overlaps the enemy’s left with its own right. This is because fear makes every man want to do his best to find protection for his unarmed side in the shield of the man next to him on the right, thinking that the more closely the shields are locked together, the safer he will be.

At Leuctra, the Spartans arrayed in standard formation, with their battle lines formed up at 8 to 12 ranks deep. This was viewed as the correct formation to ensure both adequate depth and width. In short, the considered “best practice” was to maintain a properly balanced formation, with as little drift or dissipation as possible, to prevent the formation from breaking apart altogether. A broken formation was deadly. It is estimated that, in Greek hoplite battles, losing armies lost on average nearly three times as many men as winning armies. This was the price of a shattered phalanx.

At Leuctra, Epaminondas and the Thebans threw all the conventional wisdom out the window.

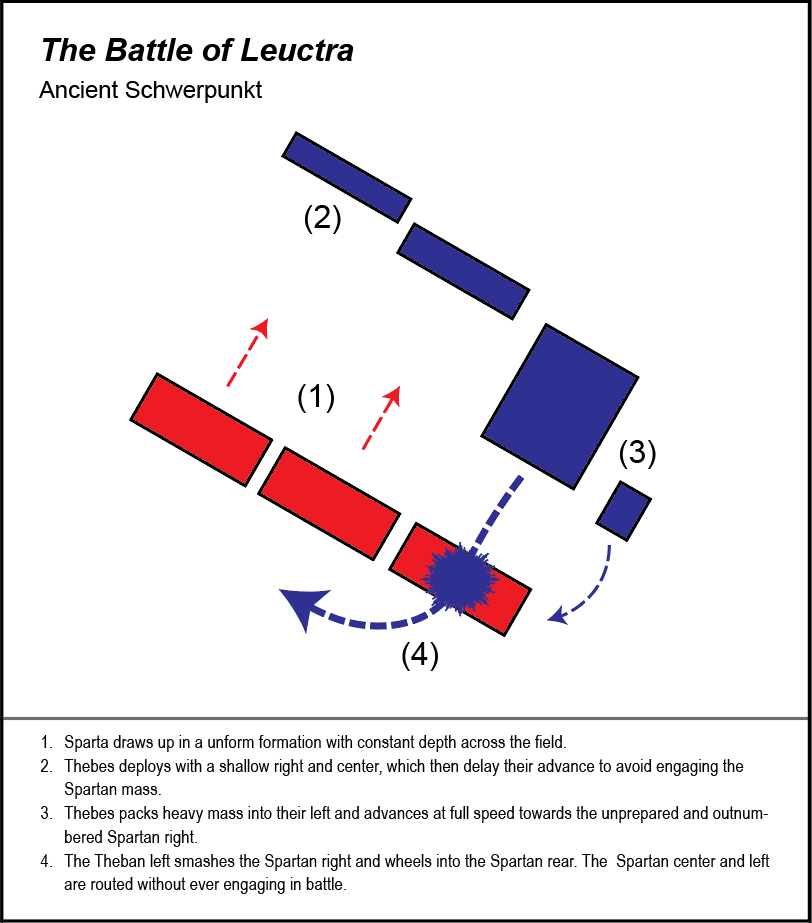

Instead of a balanced, rectangular formation, the Thebans assembled in a lopsided, weighted formation, with their left wing packed, both with far deeper ranks and their best troops. While the Spartans followed the conventional wisdom and lined up at a consistent depth all across the line, the Thebans assembled a massive package, fifty ranks deep, on the left (facing the Spartan right).

By forming up the vast bulk of their forces in the left wing (in a formation 4 to 5 times deeper than a traditional Hoplite mass), the Thebans had already deviated from one standard practice of the time. They abandoned a second standard operating procedure when they proceeded to advance that left wing far ahead of the remainder of their line. While the 50-deep left-hand mass smashed into the Spartan right, the Theban center and right lagged far behind. As a result, the mass of the overweight Theban left broke through the Spartan right wing and began to roll up the rear before the rest of the Spartan line even engaged in battle. Most of the Spartan army never got to join the battle before their formation was shattered from the rear. The Theban mass rolled into the rear, began concentric attacks on the Spartan army, and sparked a total rout in short order.

Leuctra was a titanic victory with massive geopolitical implications. The loss of an army to an outnumbered and underestimated foe rocked both Sparta’s material strength and its perception as the leading military power in Greece, and set in motion a strategic defeat that permanently relegated it to a second rate power within Greece.

The Battle of Leuctra also marked the beginning of the end of classical Greek hoplite warfare, with its focus on uniform, tactically simplified heavy infantry formations. To a modern reader, the strategy adopted by the Thebans at Leuctra, aimed at a decisive action to penetrate and exploit the enemy line, seems fairly obvious. Yet to accomplish this, the Thebans had to break a variety of “rules” for hoplite warfare, massing their forces into what the Spartans surely viewed as an unwieldy, imbalanced, and excessively deep left wing. Innovation rarely looks like innovation to those that have the benefit of hindsight, but the Thebans had, in a word, discovered the power of schwerpunkt. Thebes would itself soon be overwhelmed by another Greek power fielding similarly flexible, but even more powerful phalanx formations: Macedonia.

Epaminondas’ tactics at Leuctra marked one of the earliest documented examples of coordinated and planned battlefield maneuver. This introduced primitive maneuver into hoplite warfare, which had previously been obsessively anti-maneuver. In a very real sense, the goal of traditional hoplite warfare was to maneuver as little as possible – the line was meant to advance uniformly and evenly, without turning or staggering. The Thebans overturned this convention in one day at Leuctra and demonstrated the potential of quick drive to the enemy rear.

As for the defeated Spartans, while they never recovered from the crushing at Leuctra, perhaps they would have taken some small solace if they had known that more than 2,000 years later, it was still they, and not the Thebans, that are the icons of ancient warfare.

Rommel’s Magnum Opus

2300 years after Leuctra, heavy infantry with spear and shield were no longer the dominant weapons system. Mankind had long since progressed to ever high forms of weaponry and organization complexity in a multi-millennia pursuit of asymmetries and advantages. By the 20th century, the Prussian-German military establishment was at the height of its prowess, still attempting to use artful maneuver to bring down much larger and more capable foes.

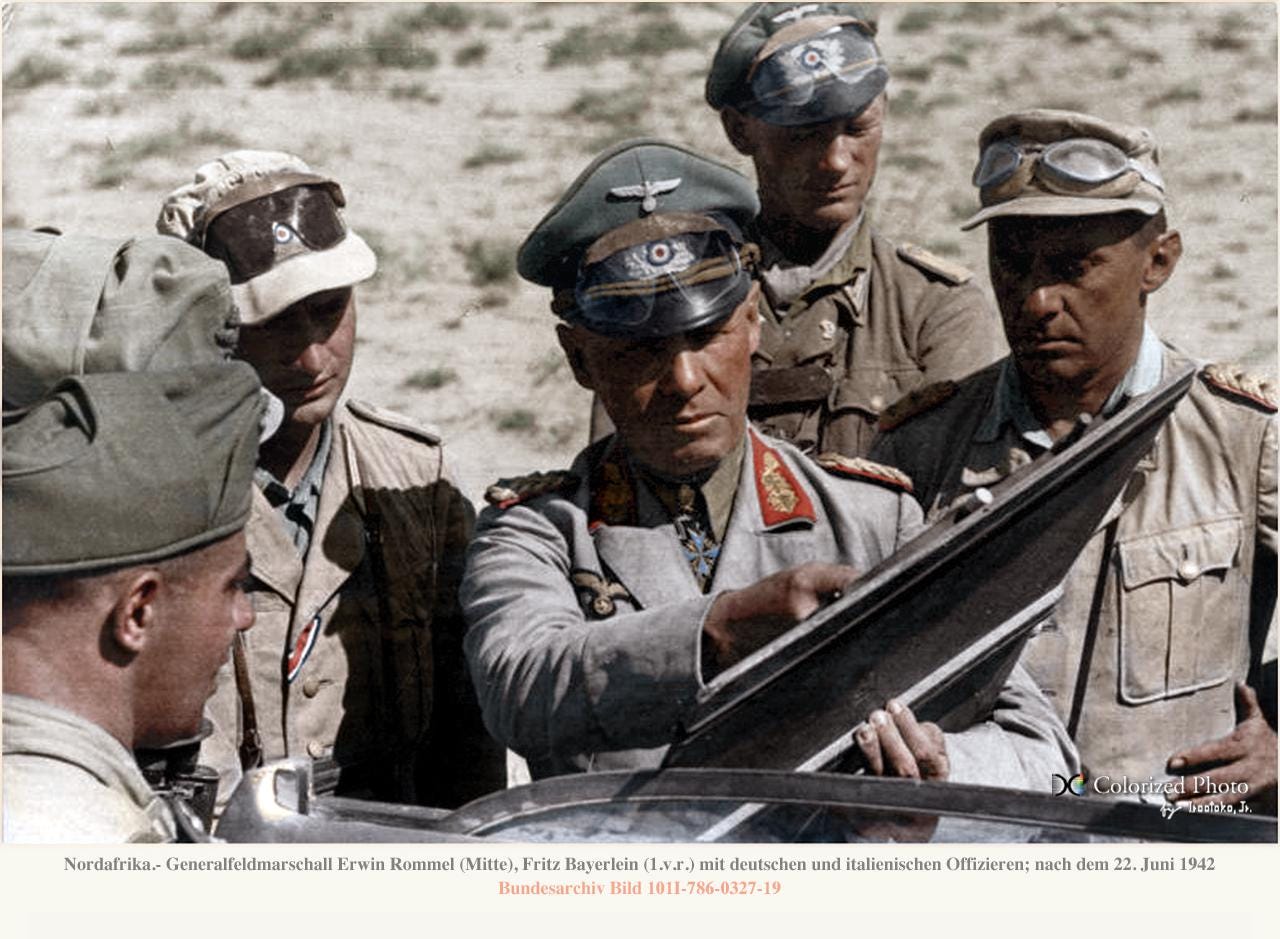

Many German operations will be considered in coming entries, but for now, let us consider an idealized example of textbook maneuver - ideal because it not only illustrates the power of concentric attacks, but also because it hints at the potential dangers of a bold maneuver scheme. This particular example also happened to be the operational masterpiece of one of Germany’s most famous commanders - Erwin Rommel.

Rommel, famously, was the man tasked with running Germany’s North Africa campaign. Both the man and the campaign are by now heavily mythologized. Rommel, in popular memory, is frequently cast as a brilliant, dashing, and - most importantly - not a Nazi. Sadly, this reflects a white-washing of Rommel’s character. Rommel showed dutiful loyalty to Hitler for years - his later tentative support for a 1944 plot to depose Hitler was motivated by his belief that the Fuhrer was botching the war, rather than any rejection of Naziism as such. Rommel’s legacy as a captivating figure is largely rooted in his campaign in Africa, where he enjoyed a mostly independent command in a large theater. While the rest of the Germany’s generals were slogging it out in mud and cold of the Soviet Union, Rommel was running free and enjoying near total operational autonomy in the desert. He looked the part, too - the sinewy good looks of a tank commander, with his goggles, binoculars, and maps, dashing about like an old school cavalryman. It is, to be sure, a compelling story.

North Africa itself, as a military theater, is similarly mythologized. On paper, the desert seems to offer the promise of total mobility and operational freedom - a wide open space that could be treated like a chess board. Unfortunately, this promised mobility was hamstrung by the main complication of desert fighting - total dependence on supply lines. In the desert, not only every shell, but every calorie, every drop of water, and every liter of tank fuel had to be supplied by truck lift or horse - making desert warfare more often than not an irritating logistical grind.

Despite these complications, Rommel did manage to produce one superb display of textbook maneuver.

The early phase of the desert war featured unbridled operational exuberance, as both the British and the Axis armies struggled to adjust to the difficulty of long range supply in the desert. The front shifted dramatically across vast distances. After arriving in Africa in March 1941, Rommel quickly went on the attack - after a sequence of small skirmishes, he burst eastward into Cyrenaica (modern Libya) and covered 600 miles in two weeks. An impressive distance - but not useful at all. No meaningful British forces were beaten (their screening forces simply retreated before him), and now he was strung out on the Egyptian border with a nightmarishly long supply line. Worst of all he had bypassed the British fortress at Tobruk, giving them a foothold from which to raid his supply. Before long, Rommel had to hoof it back to the west, shortening his lines, with the British hot on his tail, correspondingly lengthening their own supply lines.

The central issue was that the distances involved, combined with the sparseness of the desert, made it very difficult for either army to fight effectively at the extreme ranges of the theater on the doorstep of the other side’s supply bases. Not surprisingly, therefore, the front settled into an equilibrium position, with the rapid back and forth movement sputtering out near a position that would come to be known as the Gazala Line.

In sharp contrast to the stereotypical mobility of desert warfare, the Gazala position soon turned into a fortified morass reminiscent of the trench warfare of the First World War. The British, in particular, constructed a truly imposing defensive belt, complete with slit trenches, machine gun nests, mortar pits, barbed wire belts, minefields, and - their signature touch - defensive “boxes” which ensconced British units in a fully fortified, 360 degree belt of antitank obstacles and mines, offering them protection from attack in every direction.

As the two armies stared each other down across the Gazala line, diligently reorganizing, reinforcing, and resupplying, Rommel faced a classically Prussian problem. He was now faced with a protracted operation against a British army that would without question swamp him given enough time. The British already outnumbered and outgunned him. Their 8th Army now numbered a full 100,000 men supported by over 900 tanks, which included the American M-3 Grant - at this point, the best tank in action in the African theater. To match this, Rommel commanded “Panzer Army Africa” - a generous designation, with perhaps 90,000 men and a mere 561 tanks - 200 of which were lousy Italian models. In short, the British had more men, tanks superior in both numbers and quality, an apparently impregnable defensive line, and they - unlike Rommel - could expect to strengthen over time with further reinforcements and material.

This is the classic military conundrum. Rommel faced a foreboding negative asymmetry of numbers and firepower. So he took recourse to maneuver to create an asymmetry in his favor. Thus was born Operation Theseus.

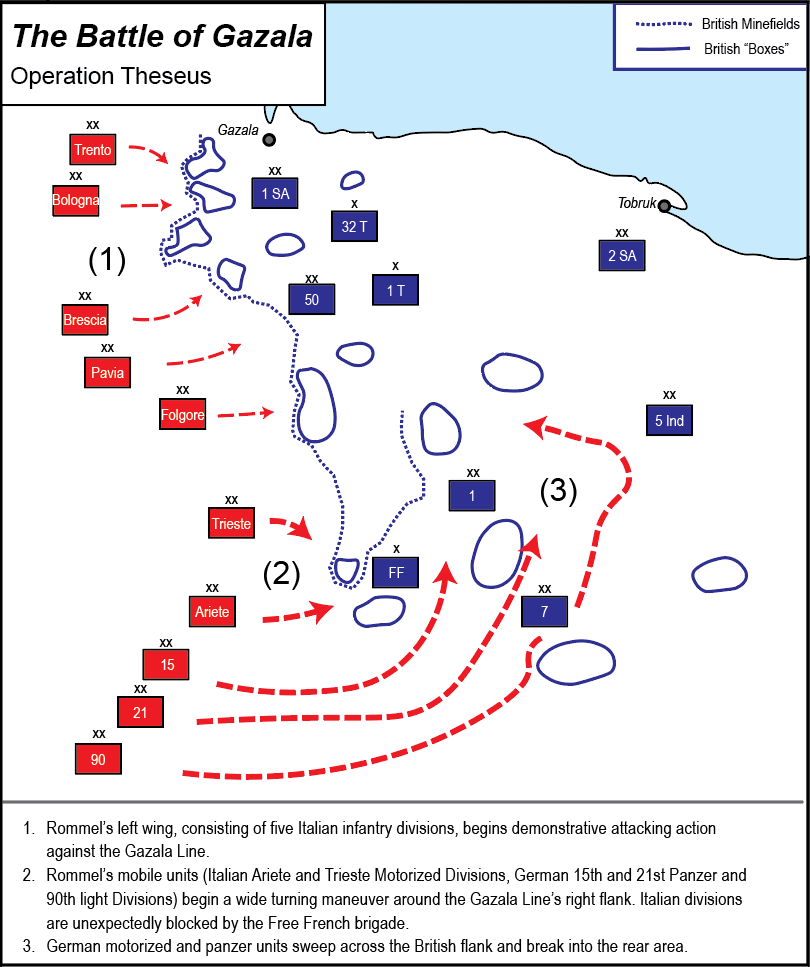

Rommel’s order of battle contained a disturbing number of Italian divisions, including five infantry divisions (most of them with naming designations after Italian cities) and two motorized divisions (“Trieste” and “Ariete”). Rommel also had two bona fide German panzer divisions (the 15th and 21st) and the 90th Light Division. The Italian infantry divisions were, bluntly, useless for any meaningful work, so Rommel assigned them to conduct a diversionary pinning attack - making as much noise as possible - on the northern (right) wing of the British line. With British attention duly fixed, Rommel launched his five mobile divisions on an epic wheeling maneuver, with the intention of getting around the southern (left) flank of the Gazala Line and driving to the sea - scooping up multiple British divisions and tank brigades in a nice clean encirclement. It was May 27, 1942 - the beginning of the greatest three weeks of Rommel’s career.

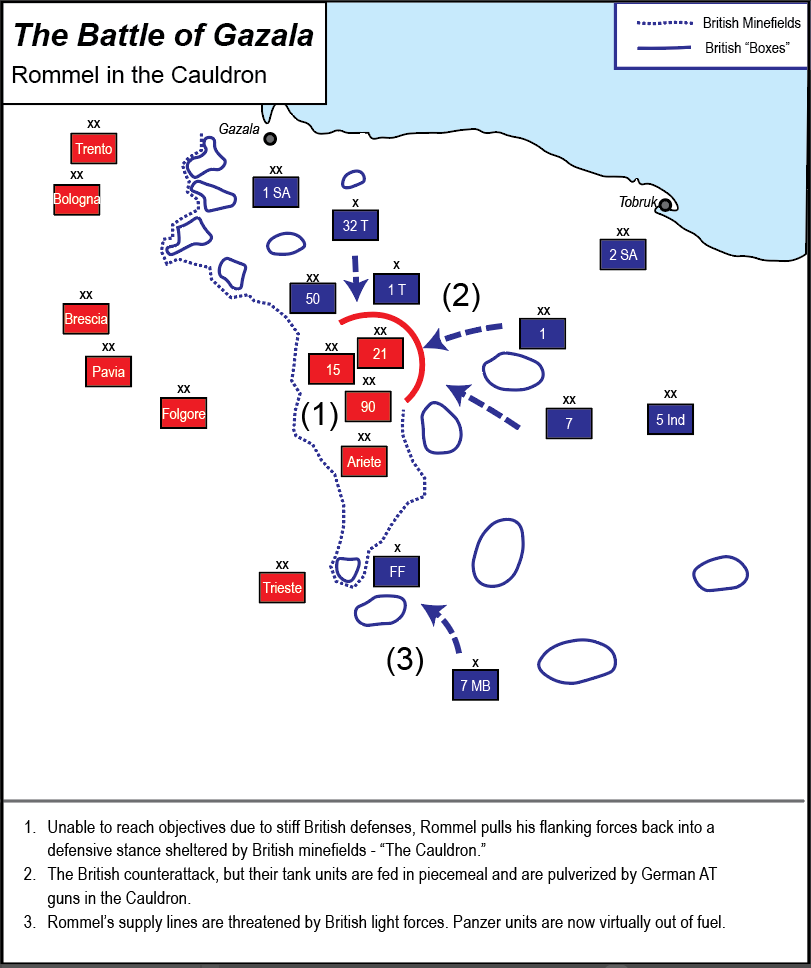

The plan, in fact, did not go very well. Rommel’s two Italian motor divisions misfired their attack horribly. Division Trieste bungled its entire path of advance, and rather than flanking around the end of the British minefields, it crashed right into them. Its sister division, Ariete, did scarcely any better, running into a defensive “box” that was fiercely defended by a Free French brigade operating with the British 8th Army.

That left just Rommel’s three German divisions, which predictably did much better than the bumbling Italians, but still fell far short of Rommel’s lofty goals. The 90th Light Division swung far out to the east where the panzers could not support it, and Rommel’s fist - his schwerpunkt, consisting of his two panzer divisions - found that progress was simply too slow and painful given the British superiority in tanks and their layered defenses.

Having swung far out into the British rear area, but unable to complete the encirclement and achieve any critical objectives, Rommel made the painful decision on May 28 to pull his units into a defensive stance, hunkering them down in pocket nestled in the British minefields. The attempt at encirclement had backfired, and it was now Rommel’s own schwerpunkt that was sitting in the enemy rear, cut off from its supply. The British knew that they had Rommel trapped, and referred to his position as “the Cauldron.”

The situation was undeniably dire. Cut off from supply by the minefields, Rommel’s forces faced the looming exhaustion of their fuel supplies. Meanwhile, the British - still enjoying superior tank strength - were preparing to smash Rommel to pieces in the cauldron. Rommel himself - had he been in the British’s shoes - would have massed all his armor and launched them in one massive strike package to wreck his encircled foe.

That, however, is not what the British did. The massed attack never came. Instead, curiously, they launched a series of uncoordinated wave attacks by single tank brigades. These were still formidable units, and Rommel’s forces took painful losses driving them off, but they lacked the consolidated mass needed to smash the German position altogether. Rommel would later allegedly quip to a captured British officer, “What difference does it make if you have two tanks to my one, when you spread them out and let me smash them in detail?”

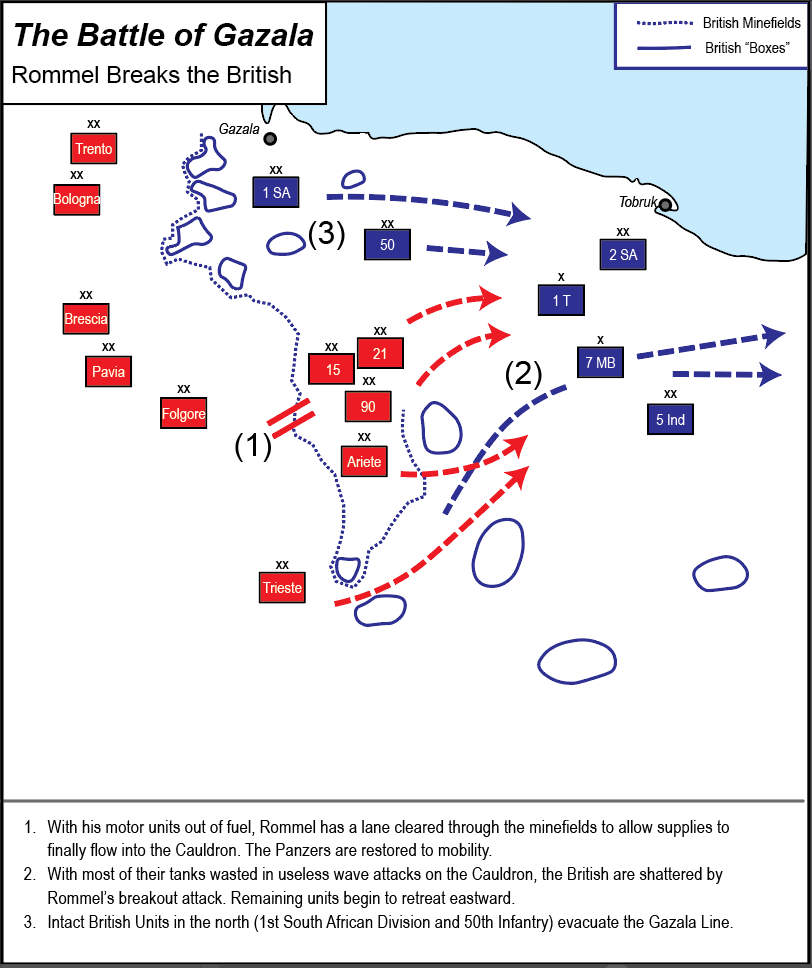

Seemingly let off the hook by the British, Rommel sprang into action. He needed to get his panzers moving again, and for that he needed gas. On May 29, he personally escorted a supply convoy through a small gap in the British minefield - getting just enough fuel into his tanks to get them moving for a bit, and working on a permanent solution. With the British tank forces reorganizing after their disastrous piecemeal attacks of the previous day, Rommel now launched an attack westward - that is, back towards his starting position. The purpose of this was not to escape, but to create a large enough hole in the British defensive lines to allow supplies, especially fuel, to flow freely through, restoring his panzers to full mobility.

With his supply problem remedied and the British command and control system seemingly incapable of putting together a sufficient mass, Rommel topped off his fuel tanks and launched the killing blow, blasting out of the Cauldron and sending the bloodied British units scurrying to the east - at least, the ones that could get away. Over 30,000 British troops would be captured at Tobruk, which finally fell in mid-June.

The Battle of Gazala is among the most instructive battles for study, as it demonstrates the full range of considerations that come with maneuver warfare - both its promise and peril.

Facing a numerically and materially superior enemy fighting from behind a well prepared defensive line, the only possible way for Rommel to emerge victorious was to concentrate his fighting power and fight a mobile battle. Launching his motorized units into the British rear was the only feasible solution - but it also very risked the destruction of his army. The schwerpunkt is a powerful tool, but if it misfires or gets bogged down in the enemy rear - as Rommel’s did - it can be cut off and destroyed. In other words, maneuver offers the potential for a decisive and rapid victory - but it also brings the possibility of a decisive and rapid defeat.

The British, however, were unable to take advantage of Rommel’s dire situation and could not smash his panzer forces once they were trapped in the cauldron. There were many issues with British command and control at this time - decision making by committee, poor coordination among units, and general indecision and hesitancy - but the battlefield result of all of these issues was a very basic asymmetry:

At all times during the crucial days of the battle, Rommel kept his firepower - particularly tanks and antitank guns - consolidated in a single mass, while the British allowed theirs to disperse. Instead of being crushed by a multi-division killing blow, Rommel was able to parry a sequence of single brigade attacks. In short, Rommel kept a schwerpunkt - a center of mass - and the British did not. On this hinged the entire battle.

In later entries, we will see what happens when the defending force, unlike the British at Gazala, is able to react quickly and with concentrated force to the enemy schwerpunkt - and we will see the terrible risk inherent in aggressive attacking maneuvers. Rommel was fortunate in his enemies, but not all commanders have been so lucky.

The Bustard Hunt

The Nazi-Soviet War was the single largest war in human history, both in the scale of the armies, the casualties, and the geographic reach of the front. Armies numbering in the many millions of men were thrown against each other on battlefields ranging over 1300 miles from Berlin in the west to the Volga in the East, and over 1200 miles from Leningrad in the North to the Caucasus in the South. Yet, for all the vast distances that would host the savagery of this war, some of the most intense and dramatic combat took place in a confined space, scarcely fifty by thirty miles, hemmed in by the sea.

Crimea is a peninsula, jutting out of southern Russia into the Black Sea, and on the eastern side of the peninsula lies yet another, smaller peninsula – the Kerch. Characterized by flat fields and small towns, the Kerch Peninsula is 56 miles from east to west, and a mere 32 miles wide at its widest point. Three of its sides are open sea, while the western edge – the “neck”, where it attaches to Crimea – is scarcely ten miles wide. By the standards of the Nazi-Soviet War, this is an unusually small and confined battleground and a natural chokepoint which leaves virtually no room for maneuvering.

In 1941, as the Wehrmacht swarmed over the western regions of the Soviet Union, the battle was rapidly carried deep into Soviet Ukraine, and by September the German 11th Army – commanded by the precocious General Erich von Manstein - was blasting its way into Crimea, dishing out horrific punishment on the Red Army forces attempting to defend the Peninsula. The issue for the German army, however, was that the confines of Crimea prevented the open maneuver that was the basis of their approach to war – the only way to break in was with a brutal frontal assault. Furthermore, there were more than twice as many Soviet divisions in Crimea as expected – the sort of failure by German intelligence that was by now becoming routine. The fight to crack open Crimea was brutal and protracted, but by November 16 all of Crimea – including the Kerch Peninsula – had been cleared of Soviet troops, apart from the imposing fortress at Sevastopol.

It was at this point that things began to go wrong for Manstein and the 11th Army. A December assault on Sevastopol failed, and while Manstein was mulling over how to crack the fortress, the Red Army successfully made audacious amphibious landings on the Kerch Peninsula. The operation was a brilliant stroke which took the Germans by surprise – having cleared Kerch, only a single division had been left behind to garrison it. It seemingly did not occur to Manstein or anyone else that the Red Army would return in force. Nevertheless, by the end of December, the Germans had withdrawn from Kerch entirely and the Red Army was on its way to landing three full armies on the peninsula – the 51st, the 47th, and the 44th. Taking Sevastopol was now the least of Manstein’s worries, with the Red Army clearly intending to take back Crimea in its entirety.

The problem for the Red Army in Kerch was the relatively straightforward fact that their commander, Dimitri Kozlov, was entirely outclassed by Manstein in every way. Alert to the new danger forming in the rear, Manstein left a blocking force to keep Sevastopol under siege and quickly moved the bulk of the 11th Army across Crimea, launching a quick attack to bottle up the Soviets in Kerch, ensuring that Germany retained control of that crucial ten mile wide bottleneck. With well over 200,000 men on either side now staring each other down in a confined space, it was obvious that substantial bloodshed was on the horizon.

Both commanders were planning offensives, but Kozlov was able to launch his first. On February 27, the Red Army launched its first attack to punch out of the Kerch Peninsula, which was promptly blown up. Its failure would be compounded upon by two additional attempts to break out, both of which suffered horrible casualties before Kozlov finally pulled back to his starting positions on April 15.

The most troubling aspect of this operation, aside from the systemic incompetence that still plagued much of the Soviet officer corps at this point in the war, was that the confined dimensions of the battlespace naturally created very dense concentrations of Soviet units, which were easy targets for German artillery and airpower – which by now was present in abundance. Manstein had demanded – and received – a substantial allocation of air support. Germany’s famous Stuka dive bombers found conditions in the Kerch to be ideal, with overpacked columns of tanks and trucks slogging through the muddy roads. In one day in March, Kozlov’s armies lost 93 tanks to Stuka attacks, and one Soviet war correspondent bemoaned that most of their losses occurred not during the attack itself, but due to relentless bombardment of the rear areas and assembly points by artillery and aircraft. This was fundamentally a confined and flat battlespace which afforded neither place to run nor hide – an idealized killing field for artillery and airpower.

This was all ideal on the defensive – but the narrow dimensions of the battlefield also presented a problem for Manstein as he planned his offensive. German maneuver warfare, of which Manstein was a practitioner par excellence, aimed to find and attack the enemy’s flanks – to surround, disorient, and destroy the enemy. What Manstein aspired to was precisely the maneuver that Rommel used to smash the British at Gazala. The difference was that Rommel had a wide open desert on the flank which he could use to seep around the British flank. In Crimea, the Red Army had no flank at all – it was simply lined up in a continuous and densely packed front across the entire width of the Kerch peninsula, from sea to sea. Maneuver seemed geometrically impossible – unable to attack a flank which did not exist, it seemed as if a bloody head on assault was the only type of operation possible. But Manstein conceived of a way out – with no natural flank available, he would use Schwerpunkt to create one.

On May 8, Manstein and the 11th Army launched Operation Trappenjagd – “Bustard Hunt.” The 11th Army consisted of two corps – the 42nd, which was stripped down to only a single German infantry division (augmented with allied Romanian forces), and the 30th, which had been correspondingly strengthened to include three infantry divisions and Manstein’s most formidable unit, the 22nd Panzer. With the weight of the 11th Army’s punching power concentrated in the 30th Corps, the attack would be heavily asymmetrical.

The operation began with the hollowed out 42nd Corps making diversionary moves and feinting attack towards the northern sector of the Soviet line. Meanwhile, the overweight 30th Corps prepared to launch a line-breaking attack in the south. Supported by a colossal concentration of Luftwaffe ground attack aircraft and a ferocious artillery bombardment, the 30th Corps broke through the Soviet frontline, and the 22nd Panzer Division poured into the gap. Manstein had created his own flank.

After driving through the gap in the southern sector of the Soviet line, the Panzers now had only a short way to go. A short drive into the Soviet rear area, a left turn, and a few miles north towards the Sea of Azov – and the entire Soviet 51st Army was now encircled. The Germans had encircled Soviet units many times in 1941, but never had an army been trapped in such a confined area, totally bereft of cover. The encircled Soviet 51st was trapped in a firebag, subjected to cataclysmic artillery fire and aerial attack by the Luftwaffe, which flew thousands of sorties. Within a few days, Soviet soldiers were surrendering by the thousands.

All that remained now was exploitation. The Soviet 51st Army was wiped completely off the board, along with most of the 47th, and the remnants of the 47th and 44th now retreated with all haste towards the city of Kerch, on the eastern tip of the Peninsula. Along the way, they were continually shredded by the Luftwaffe and relentless German artillery fire. The nature of the battlespace made it a trivial matter for Manstein to encircle the survivors; the Red Army had retreated into a corner against the sea, as the British had at Dunkirk – but this time, the Germans did not slacken off. With the Soviet survivors trapped against the sea, desperately attempting an evacuation, Manstein was able to wheel his artillery to directly overwatch the beaches and pound the fleeing Soviets from close range.

Manstein’s “Bustard Hunt” yielded one of Germany’s most complete and perfect victories of the war. Facing a Soviet army group that outnumbered this own 11th Army by nearly a 2 to 1 margin, Manstein managed to successfully scheme a classic maneuver battle of annihilation. Roughly 160,000 Soviet personnel were killed or captured in the Kerch Peninsula, in an operation that cost the Germans only 7,500 casualties – of whom a mere 1,700 were killed. Manstein achieved this by applying all the hallmarks of German maneuver – encirclement, flank attack, and exploitation – but he did so on a battlefield where no natural flank existed, and where the enemy could man an unbroken defensive line from sea to sea.

Manstein’s Crimean campaign illustrates an important application of firepower on the battlefield: an army with sufficient firepower and attacking strength always has the power create its own flank by blasting a hole in the enemy’s line and then turning right or left once it is through. In this case, the confined nature of the battlefield, combined with Germany’s colossal concentration of airpower, made it possible for Manstein to saturate a narrow section of front with explosives, and the Panzers had only a short distance to go to achieve an idealized encirclement.

However, the operation also suggested that Manstein’s great success was not likely to be replicable on the broader scale of the war, precisely because these conditions were so unique. Confined space was difficult to come by on the eastern front, and Manstein’s firepower advantage was made possible by concentration a substantial portion of the Luftwaffe’s assets on small sector – this would be one of the last times that Germany enjoyed air superiority anywhere. Increasingly, the Germans would find themselves woefully outgunned and on the wrong end of a substantial firepower imbalance – making Manstein’s Bustard Hunt a mere footnote in a losing effort. For disciples of the operational arts, however, the 11th Army in Crimea remains a potent example of operational elan, and demonstrates that even an army ensconced in what seems like a highly defensible position can find itself encircled by artful maneuver.

Summary: Single Envelopment and Concentric Attack

Leuctra, Gazala, Kerch.

Three examples of the same fundamental maneuver concept, but with radically different circumstances showing its wide applicability. That basic scheme - the foundational operational concept of maneuver is what we call “single envelopment” - the encirclement of some or all of the enemy force with a single maneuvering element - a single massed strike package, blasting into the enemy rear and making a sharp turn to scoop up the enemy force, enabling its liquidation via concentric attack.

At Leuctra, the Thebans achieved a single envelopment with a schwerpunkt comprised entirely of infantry in heavy armor - as slow as slow can be, demonstrating that maneuver is a transcendent phenomenon, which is not in any way reliant on modern technology like tanks and trucks. In Crimea, Manstein demonstrated that an envelopment scheme is possible even when there is no natural flank. Even if the enemy is entrenched from sea to sea, if the attacking force is adequately endowed with firepower it is always possible to create a flanking opportunity.

Interestingly enough, it is Rommel who had the most ideal circumstances for an enveloping maneuver at Gazala, yet it was he who experienced the most peril and demonstrates the risk that comes with an envelopment attempt. Rommel had an open desert on the flank that he could use to execute his sweeping maneuver, but he still got bogged down - and an enveloping force that fails to achieve its objective becomes very vulnerable indeed, as we will soon see.

Big Serge’s Reading List

“The Western Way of War: Infantry Battle in Classical Greece” by Victor Davis Hanson

“Men of Bronze: Hoplite Warfare in Ancient Greece” ed. by Donald Kagan

“The Grand Strategy of Classical Sparta” by Paul Rahe

“The Peloponnesian War” by Donald Kagan

“Thebes: The Forgotten City of Ancient Greece” by Paul Cartledge

“Knight's Cross : A Life of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel” by David Fraser

“Rommel Reconsidered” by Ian Beckett

“Gazala 1942: Rommel's greatest victory” by Ken Ford

“Rommel: Battles and Campaigns” by Kenneth Macksey

“Death of the Wehrmacht: The German Campaigns of 1942” by Robert Citino

“Where the Iron Crosses Grow: The Crimea 1941–444” by Robert Forczyk

“When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler” by David Glantz and Jonathan House

Wow, really good read.

Sparta's battle score over the course of its history is actually quite bad, even compared to other Greek city states. Athens is probably better overall, and of course Rome and Alexander are just so ahead...

https://acoup.blog/2019/09/20/collections-this-isnt-sparta-part-vi-spartan-battle/