Few words have electrified the military lexicon like Blitzkrieg. The word has taken on something of a paradoxical form over time - signifying so many different things that it almost seems to mean nothing at all, and yet it has universal recognition and a powerful cachet. It is, to be sure, not immediately obvious what is meant by Blitzkrieg. Is this an operational term, referring to penetration and encirclement of large enemy formations? Or is it rather a tactical designation related to the combined arms use of airpower and armor? Or perhaps it is neither - in some cases, Blitzkrieg (which means simply lightning war) is simply used to refer to any very rapid victory.

Despite the fact that nobody can seem to agree on a definition, we all seem to know what is meant by the word. By and large, what people mean is the warfighting system by which the German Wehrmacht won a series of spectacular and extremely rapid victories across the breadth of Europe from 1939 to 1941. While the precise nature of this nexus is not always well understood, Blitzkrieg stands for a certain impression of war with particular imagery associated with it: columns of panzers and trucks hauling down the road at high speed, dive bombers screeching out of the sky, a vicious attacking style characterized by extreme violence and speed, and the swastika waving victoriously from Warsaw to Paris.

It is my intention here to give a more full form to this imagery, and interpret Blitzkrieg as a particular nexus of operational, tactical, and technical systems. More specifically, the German system of warfighting that was unveiled in 1939 represented the admixture of longstanding German operational concepts (in the tradition of Helmuth von Moltke), with the infiltration and penetration tactics developed late in World War One, made technically possible through the use of mechanization, radio communication, and ground support aircraft. This system allowed the Wehrmacht to control the pace of operations by delivering high levels of sustained firepower along chosen axes of advance, fully unlocking the advantages of maneuver by seizing the initiative and never giving it back.

Blitzkrieg may have seemed to be something entirely new to the various armies that found themselves being shredded from 1939 to 1941, but in many ways it was intimately recognizable to the scions of the Prusso-German military tradition. From the very beginning, the Prussian aristocratic-officer class had always believed that winning wars was conceptually simple: find the enemy and attack him. “The Prussian army always attacks” had been Frederick the Great’s simple maxim. The tanks and bombers may have been new, but the ethos was very old indeed.

The Panzer Division

It can be said without any hint of exaggeration that the Panzer Division was the single most important and potent military innovation in the interwar period - and yet, in many popular histories, the concept is either poorly understood or glossed over. Most of the time, the idea is presented as the Germans simply “concentrating” their tanks rather than distributing them in small units around the army. This is perhaps adjacent to the brilliance of the Panzer division, but does not really address the key distinctives. Concentrating tanks was not an innovation unique to the Germans - the British, for example, developed “Armored Divisions” which packed in hundreds of tanks and few supporting units. One British General even explicitly argued that infantry “are not meant to fight side by side with your tanks in the forefront.”

The Germans, in designing the panzer division, did something unique. The panzer division, rather than being purely a tank or panzer formation, was instead a comprehensively equipped combined arms formation in which all the supportive arms were motorized to match the mobility of the tank. The result was a fast, flexible, and versatile formation with suitability for virtually any combat task.

The origins of the panzer division as a true combined arms formation lay, ultimately, with two particularly important men - one a virtual unknown named Ernst Volckheim, and the other perhaps Germany’s most famous tank commander: Heinz Guderian.

Volckheim today enjoys virtually no name-brand recognition, but he was probably the first German officer to think about armored warfare in a systematic way. He also managed to get hands on experience with tanks before Germany began making panzers by taking advantage of a curious interwar arrangement. Germany was prohibited from building tanks by the Versailles Treaty - but the Soviet Union was not. From 1929 to 1933, Germany and the USSR operated a secret joint tank-training school near Kazan, where German officers (of whom Volckheim was perhaps the most prominent) were able to get practical experience with tank tactics and maneuvers in exchange for training Soviet tank crews. Knowing how mercilessly these two armies would clash a decade later, the arrangement seems ludicrous, but it was certainly a useful tool for allowing both to get their tank forces up to speed in the 1930’s - for obvious reasons, the January 1933 appointment of Adolf Hitler to Reichskanzler fouled the relationship and brought an end to the tank school.

Volckheim used his experience at the Kazan tank school and his own musings on tank combat (the topic being his obsession) to produce a series of lectures and papers on armored warfare, which formed the first systemized treatment of what would become the German panzer arm. These strands of thought were picked up and made famous by the best known panzer commander of them all.

In one of history’s many delicious contingencies, Heinz Guderian made the cut when the Treaty of Versailles restricted the size of the German officer corps to a mere 4,000 men. With his military career thus kept alive, he spent the late 1920’s becoming something of an armored warfare guru, devouring the literature on tanks from around Europe, heavily absorbing the ideas of Volckheim, and writing several papers and short books of his own on the subject. This raised his profile and earned him a promotion to the inspectorate of motorized troops. Throughout this process, Guderian became ever more convinced of the need for a cohesive combined arms formation.

We’ll let him tell it in his own words:

In this year (1929) I became convinced that tanks working on their own or in conjunction with infantry could never achieve decisive importance. My historical studies, the exercises carried out in England and our own experience with mock-ups had persuaded me that the tanks would never be able to produce their full effect until the other weapons on whose support they must inevitably rely were brought up to their standard of speed and of cross-country performance. In such formation of all arms, the tanks must play primary role, the other weapons being subordinated to the requirements of the armor. It would be wrong to include tanks in infantry divisions; what was needed were armored divisions which would include all the supporting arms needed to allow the tanks to fight with full effect.

Guderian finally got his big chance in 1933, when he put on a field demonstration of weapons for Germany’s newly installed Chancellor. When a platoon of Panzer I’s trundled onto the field and began their maneuvers, Hitler (according to Guderian) grew very excited and shouted “That is what I want!”

By 1935, the Wehrmacht had organized its first three panzer divisions, and in 1937 Guderian published a book on armored operations titled “Achtung Panzer!” - Beware the Tank!

The composition of panzer divisions would change over time, of course, and especially late in the war they were typically far below their allotted, or “paper” strength of tanks and vehicles, but the panzer division on the eve of war was constructed roughly as follows:

A panzer brigade of some 300 tanks (organized into two regiments). This was later deemed too clumsy for division command to handle, and was downsized to a single tank regiment of 150 tanks per panzer division.

A motorized infantry brigade, including heavy infantry weapons (mortars and machine guns), and fully motorized with trucks and motorcycles.

A reconnaissance battalion equipped with light automobiles and motorcycles.

An anti-tank company equipped with truck-towed anti-tank guns.

A motorized artillery regiment bearing six truck-towed howitzer batteries for a total of twenty four guns.

A motorized field engineering battalion (called “Pioneers” in the German parlance) for construction and demolition work, including a bridging unit.

Rounding out the division would be various support elements including an anti-air (Flak) battalion, signals and communication, medical, field repair and maintenance, and a quartermaster (supplies).

As new systems were developed during war time, the loadout of the Panzer Divisions shifted away from trucks and towards more purposeful vehicles. Instead of anti-tank guns and howitzers being towed behind trucks, self-propelled artillery pieces and tank destroyers were introduced, and the infantry units swapped out their trucks for armored half tracks, but the basic design of the unit was the same. This was a self-contained fighting force with comprehensive capabilities, and everything - all the way down to the field bakery - was motorized to give it the mobility of the tanks.

The Germans had, in effect, designed the first fully motorized combined arms formation. Rather than simply saying that they “concentrated their tanks”, we should say that they concentrated their mobility. Much of the Germany army continued to consist of standard infantry divisions, which relied on good old fashioned feet and horses to get around (in 1939, only the anti-tank units in a standard infantry division would be motorized), but the panzer divisions formed a highly potent leading element to the German order of battle. On the eve of war, in 1939, the Wehrmacht had just six panzer divisions in the field (out of almost seventy divisions to participate in the invasion of Poland), but even in these limited numbers they proved to be an awesome striking force.

There was a curious irony to the vaunted German panzers. The most famous German tank models tend to be the heavily armed monsters of the late war period - the "big cats”, like the Panzer V Panther and the famous Tiger. The irony, of course, is that Germany did not begin to field these tanks until 1943, by which time they were decisively losing the war. All of Germany’s operational successes came from 1939 to 1942, when they were fielding tanks that were objectively of inferior quality to allied vehicles. For the campaign in France in 1940 - just to take a single division as an example - the 1st Panzer Division had 248 tanks in its inventories, of which 150 (60%) were either Panzer I’s or II’s - light tanks with both weaponry and armor insufficient for dueling British and French models. The Panzer I had actually been explicitly designed as a training vehicle and had no cannon at all, only machine guns, but was still deployed in large numbers in both Poland and France due to insufficient inventories of the newer models.

The great success of the panzer divisions, therefore, did not hinge on some superior fighting capability on the part of the German tanks themselves, but on the cooperative and comprehensive capabilities of the entire formation, and on its ability to move lithely and precisely. This, in turn, hinged on a solution to the command and control nightmares which had plagued armies in the first world war.

Commanders in 1914 quickly discovered that it was horribly difficult to get their large units to behave on the battlefield. The mass army was simply too large, the battlespace was too vast and complex, and communication technology was too slow and cumbersome to allow commanders to know what was going on in real time and provide their subordinates with up to date instructions. The introduction of fully motorized units like the panzer division at first threatened to make these problems even worse, because now there would be forces moving even faster and ranging ever farther from command. If controlling slow moving infantry formations was hard, directing mobile panzer units as they careened around the battlefield would be even harder.

Enter the radio - the lynchpin technical solution needed to make the entire panzer experiment work. While the radio was hardly a unique German asset, they seem to have been the first to identify it as an absolutely critical, paradigm altering technology. A series of field exercises in 1932 impressed that one very simply could not have too many radios, and by the time war began in 1939 the Wehrmacht standard was for every vehicle in the Panzer division to have a radio - not just command vehicles, as was the norm in competitor militaries.

This, then, was the strength of the panzer division: a cohesive and comprehensively equipped striking force, with its own armor, artillery, flak, infantry, engineering, reconnaissance, and anti-tank units, with every single element in the division motorized in one form or another and controlled through an integrated radio network. This was a unit that hit hard, moved fast, and could turn on a dime.

All the great power militaries in the late 1930’s had some sort of tank program. They all had radios, airplanes, and modern artillery. In fact, in 1939 the German tank park was significantly smaller than either the Soviet or French inventories. What mattered most, and a key source of Germany’s tremendous edge in combat effectiveness in the early years of the war, was their determination to create a fully motorized combined arms formation that could serve as their armored spearhead, for breaching enemy lines, driving into the rear, turning this way or that and rapidly deploying a full mechanized combat package as circumstances required.

The German military establishment had long nurtured particular views about how war ought to be fought. From Frederick the Great’s maniacal lust for the enemy’s flanks, to Moltke’s lively maneuvers against Austria and France, to Hindenburg and Ludendorff’s frustrating and futile attempts to restore operational level mobility in the Great War - this was a military tradition that wanted to get big, powerful units mobile and set them to hunting the enemy’s main body.

In the panzer division, they finally had the perfect tool for the job.

Operational Synthesis

At last, we come to Blitzkrieg. If ever there was a word which has bedeviled historians, it was this. In relatively short order, “Blitzkrieg” or “Lightning War” became the standard western parlance for the Wehrmacht’s mobile operations, and has since metastasized into a general synonym for maneuver warfare of any kind. And yet, the origin of the word itself seems to be largely an invention of western press, attempting to explain Germany’s sequence of rapid victories. The word does not appear in German military texts, handbooks, or operational drafts. Hitler decried it as “a completely idiotic word”, and Heinz Guderian dismissed it as a sloppy attempt by Germany’s enemies to explain their successes.

And yet, Blitzkrieg as such enjoys near universal cachet and has certain hallmarks or motifs - rapid movement and penetration, mechanization, close air support, and combined arms warfare. Blitzkrieg is something that most people recognize, and yet its seminal practitioners denied that it ever existed, and today the word has come to be used for any military operation characterized by speed and great violence. Robert Citino, a preeminent historian of German operations, has said that “the term blitzkrieg remains the classic example of conceptual fuzziness. It can mean so many things that, in the end, it has come to mean nothing.” Still, we cannot deny that when people speak of a German “Blitzkrieg”, they are referring to something that is clearly discernible. There’s something there - but what exactly is it?

The German officer corps in World War Two conceived of their operational art not as some entirely new form of war-making, but as a restoration and enhancement of their characteristically mobile and aggressive operations through technical, tactical, and organizational enhancements.

Let us return to a few fundamentals. The Prussian army had a long tradition of battlefield aggression which emphasized marching at top speed towards the enemy’s main body and attacking as quickly as possible. Aggression was the defining characteristic, rather than sophisticated maneuver or encirclement - for neither of these things were particularly feasible with musket armies. None of the great early-modern Prussian generals, not even Frederick the Great or Blucher, fought anything approximating an encirclement or annihilation battle. The key to their operational form was instead tempo, speed, and decisive attacking elan - closing with the enemy and savaging his main force.

It was Moltke who elevated this form to include what we would call “maneuver on the operational level” - the movement of large formations (divisions, corps, and armies) in separated, but synergistic patterns. His trademark victories over Austria at Konnigratz in 1866 and France in 1870-71 were both achieved by separating the army into dispersed formations, which then maneuvered towards each other as if to catch the enemy in a clamp.

It was after Moltke, during the uneasy runup to the Great War, that German officers began to speak of “annihilation battles”. Alfred von Schlieffen, the Chief of the General Staff, had a minor obsession with Hannibal’s ancient victory at Cannae, in which an entire Roman army was encircled and destroyed. It was hoped that modern operational planning and complex command and control systems could make it possible to achieve genuine annihilation of large armies. Germany’s operational scheme in 1914 aimed to achieve just this against the French, but the limits of mobility and communications frustrated the scheme, and they could not quite get their operational level units to move the way they wanted.

In short, Germany had an idealized form of warfare that they had never been quite able to fully realize - what they called “Bewegungskrieg”, or “Movement War”. The aspiration was to achieve genuine annihilation battles against operational targets (large enemy units like corps and field armies). They had glimpsed the ideal at Sedan in 1870, when Moltke had surrounded and destroyed an entire French army, but later attempts to duplicate the feat had failed.

In the interwar period, they realized that technical, organizational, and tactical innovations had made it possible to restore operational movement and elevate the art to hitherto undreamed of levels. The sentiment among German officers was not at all that they had created something new, but rather that they had restored their old way of fighting - Moltke’s art had been revived, on a larger and more powerful scale. One German General even wrote an article in a 1939 edition of a Wehrmacht military journal that “The most important fact, indeed, is that Bewegungskrieg, so often pronounced dead, has risen once again in its old glory.”

The technical solutions are perhaps the most obvious. Maneuver in the Great War had failed, in the final analysis, due to the deficiency of transportation and communications technology, which were still anchored to static infrastructure like telegraph and rail lines. This fact always gave the defense a decisive advantage in mobility and command and control. These advantages were obliterated with the adoption of motorization and the wireless radio. These, in a word, unchained attacking forces from their infrastructure and granted unprecedented mobility as well as reliable and instantaneous communication at all levels of the army.

The internal combustion engine and the wireless radio were not, however, the unique province of Nazi Germany. Every army had these things. What they lacked were particular German organizational and tactical innovations.

The tactics had clearly been previewed in 1918, in Ludendorff’s great spring offensive. This operation had been the great trial of Germany’s storm troopers and their infiltration tactics, which aimed to bring overwhelming firepower to bear on small, carefully selected sections of the line. The storm troops were tasked with blasting narrow breaches in the enemy defenses and moving into the enemy rear, followed by regular infantry units who would widen the breaches and spill in behind the storm units. The key aspect of these new infantry tactics were, above all, the use of high firepower units at decisive points to create breaches for the bulk of the infantry to follow through. Storm units were in other words not tasked with defeating the enemy in detail, but with penetration and paving the way for follow-on units.

The essence of Germany’s military revival can be summed up rather simply as the use of the panzer division to implement a perfected version of the storm units’ infiltration tactics, which in turn made it possible to restore operational level movement. Panzer divisions were, above all, tools for breaking through the enemy line and driving into the rear, paving the way for the standard infantry units which formed the bulk of the Wehrmacht. In this way, the panzers created the conditions for encirclement, but they did not liquidate encircled enemies themselves - that task was left to the infantry units that trailed behind them.

The power of panzer divisions to create breaches and force holes in the enemy defense was formidable, and made possible by their ability to direct a tremendous amount of firepower at narrow sections of the enemy front, both with their organic tank and motorized artillery and with close air support.

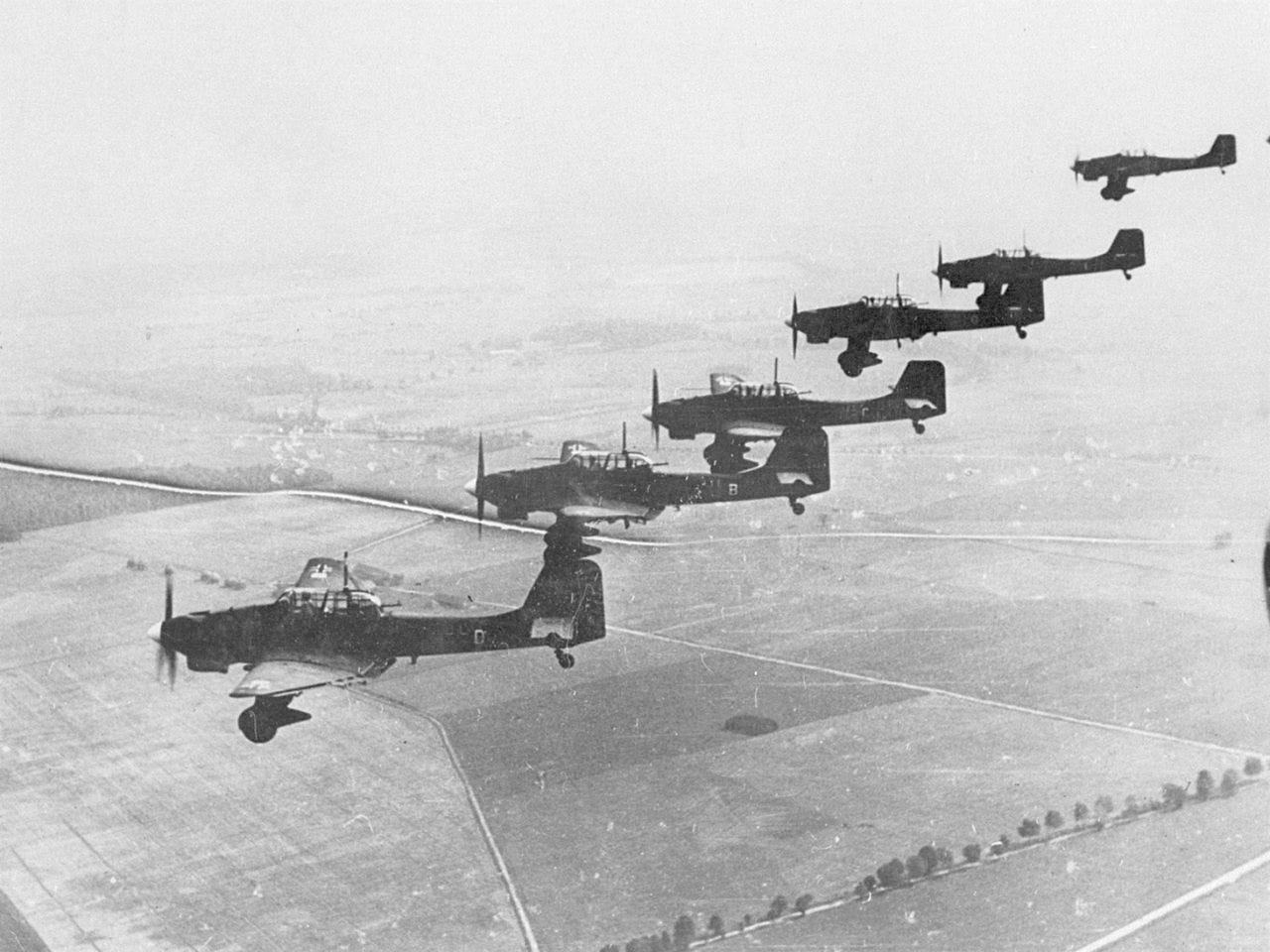

The extensive nature of Germany’s radio network made it possible to coordinate precise air support - most famously with the iconic Stuka dive bombers. The Stuka is a legendary aircraft that remains instantly recognizable. As a boy, I felt that I could spend hours staring at pictures of them, basking in the brute magnificence of the gull wings and fixed landing gear. The experience of coming under aerial attack was terrifying, with the Stuka’ infamous sirens screeching as it dove at nearly a ninety degree angle on attack. Leaving aside the psychological effects, however, the combat meaning of Luftwaffe close air support was to provide a surge of firepower at the point of attack.

The German panzer attack package was truly terrifying. Weak sections of enemy front were carefully selected; tank columns deployed off the road and roared through gaps in the line, discharging fire as they went. The division’s towed (later self propelled) artillery unlimbered into batteries and began pounding - their fire corrected by organic reconnaissance elements, while Stukas swooped out of the skies to disgorge their bombs. Infantry followed the panzers into the breach - dismounting from their trucks and pouring in fire from machine gun, mortar, rifle, and grenade. When overwhelmed defenders tried to retreat, they frequently found the panzers on the road behind them in blocking position. This was a tactical package predicated on overwhelming firepower and violence at narrow points, and it was terribly efficient.

The final ingredient required to make this fearsome fighting machine tick was also the secret repository of Germany’s strength: the officer corps. Despite the strictures of the Versailles settlement, Germany approached the next war with a robust and highly trained officer corps that formed the nucleus of a rapidly expanding Wehrmacht. This was owed largely to the efforts of Hans von Seeckt, Chief of Staff in the years after the Great War. Seeckt believed strongly that war was an unavoidable aspect of human political life, and that no matter what the treaty said, Germany must be prepared for the next war. With the officer corps being limited by the treaty to only 4,000, Seeckt took two measures. First, all the remaining officers were trained to command units higher than their paper grade (so that although the 4,000 included officers of every rank, in educational terms it was stuffed with majors and higher), and secondly the army focused on perfecting its training programs and maintaining academies so that the officer corps could rapidly expand when the time came. Seeckt, perhaps even moreso than Guderian or Volckheim, thus became the true progenitor of the Wehrmacht’s great victories.

It was not simply that that German officers were well trained - it was that they were all trained to see war the same way. The German academy inculcated a preternatural sense of battlefield aggression and decisiveness. In other words, the mobile and attacking campaign was driven by the aggression of officers from the bottom up. Orders rarely had to come down from high command to attack; more often, high command was informed that the attack was underway.

This was coupled with the army’s tradition of independent decision making by commanders in the field. It has become fashionable today to speak of “Auftragstaktik” - so called “mission based tactics”. The notion here is that commanders issued objectives, rather than detailed instructions, and left it to subordinates to decide the best way to achieve the objective. As in the case of Blitzkrieg, however, Auftragstaktik is a term that the Germans themselves did not widely use. They were much more prone to speak of the tradition of the independence of the commander in the field. What this meant, very simply, was that going back to the time of Frederick the Great, a Prusso-German commander who saw an opportunity to attack the enemy was virtually never reprimanded (let alone punished) for taking it. German history was full of aggressive field commanders who threw off larger plans and orders because they saw a chance to grab the enemy and kick him in the face, and the Wehrmacht likewise acknowledged (at least in the first years of the war) the prerogative of the commander in the field to attack.

This created an implicit, rather than explicit communication within the army, with the entire body organically seeking a mobile and attacking war. This system brought Germany an unprecedented sequence of victories across the breadth of Europe between September 1939 and December 1941. From Paris in the west to Kiev and Smolensk east; from Norway to the Mediterranean; in the mountains of the Balkans, on the island of Crete, in the fjords of Scandinavia, and in the fields of France - the Wehrmacht simply won.

The Demonstration: Poland, 1939

Amid the enormous mass of content on the Second World War - books, documentaries, films, and so on - the opening campaign of the war generally gets short shrift. Given the enormity of what was coming down the pike - both in the magnitude of the campaigns, variegated horrors and crimes against humanity, and the metastasization of conflict over six years and across multiple continents - the Wehrmacht’s lively little romp in Poland in the September of 1939 seems relatively small and unimportant. Poland’s fate is so certain, her fight is so hopeless, and her tragedy is so great that the actual operational details of Germany’s campaign seem like an irrelevant distraction on the road to bigger and more terrible things.

It is a fairly unambiguous fact that Poland had no real chance of winning a military victory in 1939, largely because of the tremendous diplomatic bungling by the country’s leadership. Without going too far into the weeds of interwar intriguing and alliance-making, we can simply say that Polish security was predicated on a fundamentally untrue premise. Sandwiched between two much more powerful states (Germany and the USSR), Polish leadership was convinced that their country’s security depended on maintaining a neutral balance between the two. Neither Germany nor the USSR, went the reasoning, would attack Poland for fear of driving Warsaw into alliance with the other. Seeking to be a balancing force, the Poles never seem to have really contemplated that Moscow and Berlin might simply agree to destroy Poland together, simply to clear the map of limitrophe states. This indeed is what happened with the signing of the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, better known to history as the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact.

Poland’s fate was more or less guaranteed, given the fact that she had no allies with contiguous borders (and thus there was nobody who could immediately offer meaningful assistance), and she was now slated for invasion from almost every direction. We can thus say without any real controversy that from the time the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was signed on August 23, 1939, it was more or less a forgone conclusion that the 2nd Polish Republic would be destroyed.

This, however, is a general statement about the fate of the state. The particular way that the Polish Army was destroyed by the Wehrmacht was an entirely different matter - a technical one, which shocked the world with its speed and violence.

The Wehrmacht was obviously the prohibitive betting favorite against the Polish armed forces, though not quite for the reasons that people general believe. There remain stubborn stereotypes about Polish backwardness, and in particular the story is still retold that Polish cavalrymen with lances engaged German tanks in combat. This almost certainly did not happen, and was probably a story invented by the German propaganda apparatus to demonstrate how primitive and slavish the Poles were.

In fact, the Polish army was as large, professional, and well equipped as one could have asked for given Poland’s economic and demographic resources. The Poles had inventories of modern and effective artillery and anti-tank guns, including a 75mm model which proved perfectly capable of shredding 1939 vintage Panzers. Poland even had a tank park of its own, which while not up to German or Soviet standards was larger and more advanced that the American inventory at the time.

The problem was not that Poland was a primitive state with a 19th century army. The problem was that they were not only outgunned but woefully outmatched on the operational level by the Wermacht’s attacking elan. The manpower advantage was not particularly decisive: Poland fielded some 376 infantry battalions against the Wehrmacht’s 559, or roughly a 50% German advantage. By the time Polish reserves were mobilized, the numbers were nearly even - some 1.5 million German troops against 1.3 million Poles. However, German forces enjoyed a much higher density of heavy weaponry. So while the Germans had only a slim margin in manpower, they had nearly three times as many heavy artillery pieces, and more than five times as many anti-tank guns and armored vehicles as had the Poles.

The critical factor from the operational perspective was the fact that, by September 1939, Germany more or less bordered Poland on three sides. East Prussia, located on Poland’s northern flank, was separated from the rest of Germany by a thin strip of Polish territory commonly called the Danzig corridor. To the south, Germany’s annexations in former Czechoslovakia had pushed German territory further to the southeast. As a result, much of Polish territory had become an enormous salient vulnerable to invasion from three different directions.

Sadly, Polish command - once it became clear that war was coming - opted for a disastrous deployment plan which attempted to defend everything by placing Polish defensive lines at the perimeter of the country. In contrast to western naming conventions which usually designates armies with numbers, Poland’s scheme mobilized multiple field armies which were named after key cities in their operating zones (IE, Cracow Army in the southwest, Lodz Army in the center, and so on). No less than five such armies were forward deployed near the borders.

This forward deployment scheme, which generally aimed to defend the maximal extent of Polish territory, put much of the Polish army in an exposed position - a weakness which was amplified by the fact that most of the Polish rear area infrastructure (ammunition depots, troop concentration sites, and the like) were actually placed in the western part of the country, due to previous assumptions that the most likely invader would be the Soviet Union. Since the Red Army would be invading from the east, military infrastructure had been built in the rear (the west), which was now the front. In short, much of the Polish military apparatus was held out at arms length for Germany to snatch it.

Nobody particularly expected that Poland could defeat Germany. Still, Poland was able to field a million men, supported by hundreds of armored vehicles, airplanes, and heavy weapons. They were disciplined, brave, professional, and highly motivated. Outmatched, yes, but the first world war had demonstrated that these sorts of states could still be very difficult nuts to crack. Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania had all managed to hold out against the great powers for months, and Poland was far more powerful than any of them. Even outgunned as they were, it was hardly expected that the entire Polish Army would be shattered in 12 days.

The German deployment plan formed two army groups. A northern grouping comprised of five corps was tasked initially with liquidating the Danzig corridor and connecting East Prussia with Germany proper, while a much larger ten-corps southern grouping wielded the bulk of the striking power, including 4 of the Wehrmacht’s six panzer divisions.

Given that Poland had come to resemble an enormous salient, the concentric movement of these army groups towards each other would press the bulk of the Polish forces in between two enormous pincers. This was an operational concept firmly rooted in the traditions of Moltke, in that it aimed to maneuver independent armies towards each other and catch the enemy mass in the middle. Indeed, this is precisely what happened, though the speed and ferocity of the operation was shocking.

The German invasion began before dawn on September 1, with Luftwaffe bombers infamously attacking the town of Weilun as German ground forces launched off their start lines. The basic problem - almost immediately evident - was that the Poles simply had no answer for the German assault package, which concentrated, as we have said, very heavy firepower at narrow points before bursting at high speed through the gaps. Given that the Germans had advantages in every heavy weapons class to begin with, the Polish decision to try and man the entire frontier ensured an overwhelming German firepower advantage at the chosen breaching points.

The panzer units, of course, served as the deepest driving spearheads, but the paucity of panzer divisions meant that much of German fighting power came from infantry divisions. Even with virtually no armored forces in some sectors of front, the Germans broke through almost everywhere and soon were deep in the Polish rear. By September 8, some of the leading panzer units from Tenth Army had already reached the outskirts of Warsaw, while Cracow, farther to the south, had already fallen by September 6th.

The broader issue, operational speaking, was that entire Polish armies were on the verge of complete encirclement. Cracow Army attempted to withdraw into the interior to the northeast, but by this time two great thrusts from the German 14th Army were well behind it. Units of Pomorze Army were encircled and destroyed in the Danzig corridor in the opening days of the war.

Perhaps the most startling situation, however, faced Poland’s Poznan Army. Tasked with the most westerly sector of frontage, it faced no major German combat formations at the outset of hostilities - only border guards. Untouched, but doomed: the German pincers were closing behind it. It attempted a half hearted withdrawal back towards Warsaw, but the speed of the German advance made it only a formality when it was bottled up well to the west of the Vistula, along with the frantically retreating remnants of Lodz army.

By September 12, all Polish forces west of the Vistula were operationally neutralized - that is, they were either destroyed or caught up in encirclements of various sizes. It was impossible for the Poles to stabilize any sort of front or even assemble meaningful rear echelons, because the German advance reached assembly areas while the mobilization was ongoing. The so-called “Prusy Army” - intended to be the primary strategic reserve - had to mobilize directly into active combat, with Polish infantry attempting to debark their trains right into the face of the full German mechanized package - panzers, artillery, and Stuka attacks. Individual Polish small units fought bravely and knocked out panzers here and there, but there was simply nothing that willpower could achieve here other than the honorable discharge of individual duty. Operationally, the Polish Army’s back was broken on contact.

The standout unit, perhaps, was the 19th Corps, lead by none other than hard hitting Heinz Guderian. Wielding the 3rd Panzer Division and a pair of motorized infantry divisions, Guderian was first on the scene crossing the Danzig corridor and linking up with the German army in East Prussia. With this accomplished, he took his corps on a fantastic cross country drive - crossing all the way over the lines of operation of 3rd Army - and ending up far to the east of the Vistula. This somewhat fouled the situation map - Guderian’s entire corps was “out of line”, so to speak, and ended up far away from the rest of Fourth Army. But he had driven far and dealt out terrific damage, and this was precisely the sort of battlefield initiative that the German military tradition was designed to tolerate and inculcate. No commander would expect to be punished for getting after the enemy too vigorously - and Guderian would show forth more wonders yet.

History books will generally say that the Polish campaign lasted for 35 days - marking the days from the outset of hostilities on September 1 to the surrender of the last active regular Polish army units on the night of October 5-6. In fact, the cohesive defense of Poland on the operational level lasted for eighteen days at most. By the second week of the war, the Polish army had been broken into disparate pockets which continued to fight bravely but futilely - in encirclements on the west Polish plain, in besieged Warsaw, and in individual units retreating eastward. By September 19 (hence, the common German reference to an “eighteen days campaign) the entire country had been overrun with the exception of Warsaw. At the time that the Red Army joined the war with its infamous invasion of the Polish rear on September 17, there was nothing in the way of operational level resistance remaining, and Soviet casualties were correspondingly very light.

Casualties in the Polish campaign revealed the coming pattern of the Wehrmacht’s attacking operations. Polish losses were, of course, terrible virtually everywhere. Killed and wounded ran up to 200,000 men, most in the first two weeks of fighting. It was in the captured category, however, that Polish losses swelled to obscene levels. Those deep drives into the Polish rear areas - big arrows, moving with sustained momentum and overrunning secondary lines of defense - allowed for the capture of tens, or even hundreds of thousands of men in enormous Kessels, on the mold of Sedan. All told, the Germans took some 587,000 prisoners. It was these encirclements and the resulting mass surrenders which allowed the Wehrmacht to wipe the bulk of a million man army off the field at the cost of only 11,000 dead and 30,000 wounded of their own.

The German reaction of course included a fair amount of jubilation (and soon a great deal of cruelty in occupied Poland), but the German officers corps mainly seemed to exhibit relief that mechanization, the radio, and the Luftwaffe had now allowed them to fight the way they’d always wanted to. Operationally, the entire scheme would have been intimately familiar to Moltke or Ludendorff, but now the Panzer and the Stuka provided firepower deep in the operational space, allowing tactical breakthroughs to be converted into true operational victories. This was, in other words, a marriage of modern technical solutions with traditional German operational sensibilities - and the results spoke for themselves. One general wrote in the Werhmacht’s military magazine:

The essential difference between the conduct of the current eastern war and that of the World War is that the present army has both armored and motorized formations. They turn each tactical breakthrough into a rapid and comprehensive operational one. In the World War, because of our lack of tanks, this was possible only through a long continuation of the attack, sometimes stretching out for weeks.

Of course, doubters would always point to Poland as perhaps a less than ideal demonstration of this new war-making synthesis. Fair enough. It was to be sure a second tier power with weapons inferior both in quality and quantity to German models, fighting in a geographically impossible position. But in any case, the Wehrmacht could ill afford to simply rest on its laurels. They may have been unable to save the Polish Republic, but the French and the British had at last been stirred out of apathy and declared war on the Reich.

Poland was crushed, but the Germans now faced the horrifying prospect of refighting the western front: A second descent into hell? Or a chance at martial redemption for a resurgent Germany army?

The Pinnacle: France, 1940

Amid several years of essentially uninterrupted military successes, no campaign better exemplified German ascendance in Ares’ domain than the spectacular defeat of France in 1940. The rapid destruction of a modern and well-equipped French army - achieving in six weeks what the Kaiser’s army had been unable to do in 4 years - and the dramatical reversal of the humiliation at Versailles (the French were famously forced to sign surrender documents in the same railcar where the Armistice had been imposed in 1918) seemed to signal a complete German revival and the comprehensive overturning of the Great War.

It was, to be sure, a victory without compare, either before or after. France was a peer competitor to Germany in every way, and yet she suffered a total strategic defeat in a campaign so short that it beggared belief. The rapidity and totality of German victory over a rival great power will likely never be matched.

And yet, the campaign itself was curious - almost serendipitous, in fact. At the beginning, the German general staff had no plans for an ambitious coup de main. There was no long premeditated blitzkrieg. In fact, the original German operational scheme was remarkably lame. It amounted to little more than a repeat of the Schlieffen-Moltke Plan, yet was even more restrained in its objectives. The plan first presented to Hitler called, yet again, for an army group to swing northward through the Netherlands and Belgium - yet the stated objective was not to defeat France outright, but only to destroy the Belgian army and capture bases and territory to set Germany up for a longer war against the French and British.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Big Serge Thought to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.